Образец проекта_информация о писателях

реклама

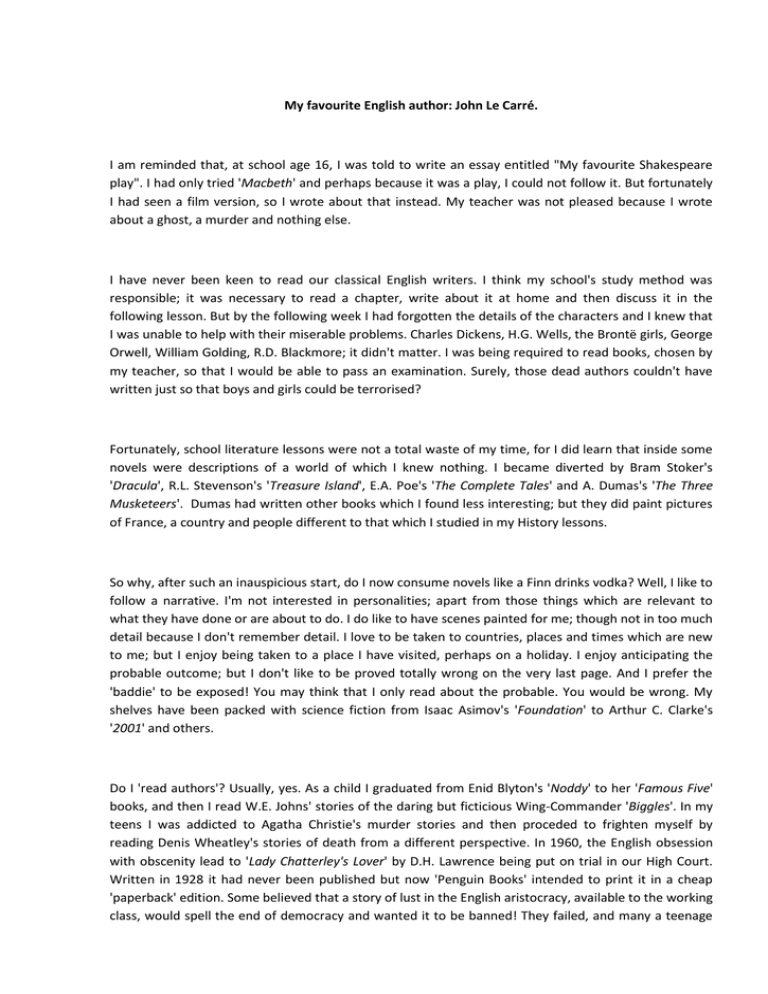

My favourite English author: John Le Carré. I am reminded that, at school age 16, I was told to write an essay entitled "My favourite Shakespeare play". I had only tried 'Macbeth' and perhaps because it was a play, I could not follow it. But fortunately I had seen a film version, so I wrote about that instead. My teacher was not pleased because I wrote about a ghost, a murder and nothing else. I have never been keen to read our classical English writers. I think my school's study method was responsible; it was necessary to read a chapter, write about it at home and then discuss it in the following lesson. But by the following week I had forgotten the details of the characters and I knew that I was unable to help with their miserable problems. Charles Dickens, H.G. Wells, the Brontë girls, George Orwell, William Golding, R.D. Blackmore; it didn't matter. I was being required to read books, chosen by my teacher, so that I would be able to pass an examination. Surely, those dead authors couldn't have written just so that boys and girls could be terrorised? Fortunately, school literature lessons were not a total waste of my time, for I did learn that inside some novels were descriptions of a world of which I knew nothing. I became diverted by Bram Stoker's 'Dracula', R.L. Stevenson's 'Treasure Island', E.A. Poe's 'The Complete Tales' and A. Dumas's 'The Three Musketeers'. Dumas had written other books which I found less interesting; but they did paint pictures of France, a country and people different to that which I studied in my History lessons. So why, after such an inauspicious start, do I now consume novels like a Finn drinks vodka? Well, I like to follow a narrative. I'm not interested in personalities; apart from those things which are relevant to what they have done or are about to do. I do like to have scenes painted for me; though not in too much detail because I don't remember detail. I love to be taken to countries, places and times which are new to me; but I enjoy being taken to a place I have visited, perhaps on a holiday. I enjoy anticipating the probable outcome; but I don't like to be proved totally wrong on the very last page. And I prefer the 'baddie' to be exposed! You may think that I only read about the probable. You would be wrong. My shelves have been packed with science fiction from Isaac Asimov's 'Foundation' to Arthur C. Clarke's '2001' and others. Do I 'read authors'? Usually, yes. As a child I graduated from Enid Blyton's 'Noddy' to her 'Famous Five' books, and then I read W.E. Johns' stories of the daring but ficticious Wing-Commander 'Biggles'. In my teens I was addicted to Agatha Christie's murder stories and then proceded to frighten myself by reading Denis Wheatley's stories of death from a different perspective. In 1960, the English obsession with obscenity lead to 'Lady Chatterley's Lover' by D.H. Lawrence being put on trial in our High Court. Written in 1928 it had never been published but now 'Penguin Books' intended to print it in a cheap 'paperback' edition. Some believed that a story of lust in the English aristocracy, available to the working class, would spell the end of democracy and wanted it to be banned! They failed, and many a teenage boy, including me, furtively crept into a bookshop and left with an anonymous brown paper bag. The story bored me, Penguin Books became rich and 'Royal Wedding fever' is here again. I never read any of Lawrence's other books. By 1963, television was competing with the syrupy love stories and the easy-to-follow USA 'Cowboys and Indians' and propaganda style films based upon our 'Second World War'. Film fought back and it discovered a genre based upon the 'Cold War', as we called the distrust between the 'West' and the 'USSR'. Countless boys, including me, rushed to the cinema to see Ian Fleming's English secret agent, James Bond - 007 in 'From Russia With Love'. We were able to learn at first hand the truth about the USSR. From its devious leaders, its iron-chested military, it's technologically advanced weapons and its world-devouring ambitions to its indescribably beautiful, male-devouring women, we learned about a secret world. Fortunately, his other stories taught me that, with the exception of the Russian women, much of Fleming's imagination was fanciful and relied upon stereotypes. However, I was well and truly hooked on these stories of clandestine meetings and dubious agreements, of single-minded and determined individuals seeking solutions in an uncertain world, when one of Len Deighton's books, 'The Ipcress File', was filmed in 1965. And then I discovered Frederick Forsyth. I don't remember the order in which the book, the film and the terrorist came into my life but I do know that, in 1975, 'The Day of the Jackal' blew away the fluffy, improbable, silliness of James Bond. I recall being amazed that the 'scenery' was the same inside the book as it was upon the screen. There was also a real international terrorist and our newspapers christened him 'Carlos the Jackal'. Forsyth continued to write his stories - which were set against backdrops created by the biggest foreign news stories of the time; I was always hungry for his next. But whilst I waited, who did I read and re-read? David John Moore Cornwell was born in 1931 and worked for the both British Military Intelligence Service's MI5 and MI6, and during this time he wrote three books under the pseudonym, 'John Le Carré'. In the 1960's our news reports were dominated by a story about four Englishmen who were sending classified information to the USSR and it was believed that the identities of many British Intelligence officers had become known; and so they lost their jobs. Fortunately for Cornwell his third novel, 'The Spy Who Came in from the Cold', had become a world-wide success and so, when he left the Service, he started to write full-time. Le Carré's main Cold-War characters are unremarkable people doing mundane work. They think a lot and fight very little. Whilst the author clearly knows where his story is going, the characters in the book do not; and neither does the reader. For some people this style of writing is intolerable; for progress seems to be very slow and skipping pages does not help because the reader finds himself in a strange place disconnected from that which has already read. Such is the strategy and style with which Le Carré leads the reader on his journey through his novels. In 1989 the Berlin news was amazing, but I thought that Le Carré would write no more. He had mislead me. Le Carré's hero's are non-judgemental; at least in the political sense. He prefers to explore the 'inter-personal', such as honour, honesty, right, wrong, trust and betrayal. He knows about the geography and lives of people and places where few English people go, so he can set his stories on any continent. In this way he continues to allow his readers to test their feelings and beliefs in the areas of international politics, business and human rights. His latest novel 'Our Kind of Traitor' is set in Antigua and concerns a Russian oligarch. I will read it later this year. Before then, I will read Ken Follet's 'Fall of Giants'. Perhaps Robert Wilson will take me back to Spain or Peter Robinson will describe another murder, not 50 miles from where I am writing. You may read about each of these authors on www.wikipedia.org ...... and in cyrillic. Chris N. L. France. Durham. 2011 American writers. Don DeLillo (born November 20, 1936) is an American author, playwright, and occasional essayist whose work paints a detailed portrait of American life in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. DeLillo's novels have tackled subjects as diverse as television, nuclear war, sports, the complexities of language, performance art, the Cold War, mathematics, the advent of the digital age, and global terrorism. He currently lives near New York City in the suburb of Bronxville. DeLillo was born on November 20, 1936 and grew up in a working-class Italian Catholic family in New York City. As a teenager, DeLillo wasn't interested in writing until taking a summer job as a parking attendant, where hours spent waiting and watching over vehicles led to a reading habit. Among the writers DeLillo read and was inspired by in this period were James Joyce, William Faulkner, Flannery O'Connor, and Ernest Hemingway. After graduating from Fordham University in the Bronx with a bachelor's degree in Communication Arts in 1958, DeLillo took a job in advertising because he couldn't get one in publishing. He worked for five years as a copywriter at the agency. DeLillo published his first short story, "The River Jordan" in 1960 and began to work on his first novel in 1966. Among his important novels are White Noise, Libra (1988), Mao II (1991) and Falling Man (2007). DeLillo published Point Omega, his fifteenth novel, in February 2010. The possible idea is that human consciousness is reaching a point of exhaustion and that what comes next may be either a paroxysm or something enormously sublime and unenvisionable." A теперь предлагаем вашему вниманию подготовленный проект по заявленной теме: English Literature Class ПРОЕКТНАЯ РАБОТА С УЧАЩИМИСЯ СТАРШИХ КЛАССОВ Проектная технология используется в 10–11-х классах на уроках английского языка, англо-американской литературы и мировой художественной культуры. Поэтапно отрабатываются элементы проектной технологии, и учащиеся осваивают проектную деятельность постепенно, от простых микропроектов – 30–40 минут (1 урок), до долгосрочных – исследовательских и художественных, выполняемых по всем законам и правилам данной технологии. Один из проектов в курсе английского языка связан с изучением темы “Вечные ценности”. Команды, сформированные из трёх языковых подгрупп, “защищали” свою систему непреходящих нравственных ценностей в художественной форме, творчески переработав результаты своей исследовательской и практической деятельности. Осуществлён проект по внеклассному чтению на английском языке (романы А. Хейли) и теме “Выбор профессии” в одной языковой группе, где также использовалась исследовательская и практическая деятельность учащихся, а защита проходила в деловом, но творческом стиле. На одном из уроков англо-американской литературы учащиеся одной группы (14 человек) защищали филологический проект, связанный с изучением творчества современного английского автора Дж. Арчера. На основании анализа ряда произведений учащиеся вывели “формулу” писателя. Итоговым занятием в курсе мировой художественной культуры на английском языке стал большой проект “Азбука искусства”, осуществлённый учащимися 11 класса (26 человек). Защите предшествовал длительный этап поиска материалов, написания рефератов, обсуждения формы выступлений, репетиции и др. Данные формы проектной работы оказались плодотворными как для изучения указанных предметов, так и для развития практических навыков и умений учащихся, а также для их общего развития, интеллектуальной, социальной и психологической зрелости и укрепления коллектива. Сейчас в общешкольном проекте “Мир, терпимость, ненасилие” заняты и восьмиклассники по предмету “Страноведение”, и девятиклассники в курсе “Введение в англо-американскую литературу”. Form: project Students: 11th formers, a group of 14 students Place: classroom Time: 90 minutes – a double period Previous home assignment – to read the following short stories by J. Archer, e.g. “Just Good Friends”, “Old Love”, “The Hungarian Professor”, “Not the Real Thing”, “The Chinese Statue”, “The First Miracle”, “Christina Rosenthal”, etc. (See the collections A Twist In The Tale, Twelve Red Herrings, A Quiver Full Of Arrows, The Collected Short Stories, Harper Collins Publishers, 1990s.) Objective – to work out “The Archerian Formula”. Each of the three teams is offered the same task. They should enrich each other. Additional information – article on Genre Fiction (see Cambridge Guide to Fiction in English, Ian Ousby). Previous experience – stories by W. S. Maugham, O’Henry, R. Dahl, K. Mansfield, E. M. Hemingway, G. Greene, H. Munro (Saki), P. Lively, et al, and their literary analysis. Literary analysis algorithm. Among the conclusions about “the Archerian formula” (or his “tricks of the trade”, or his basic methods of writing), drawn by the project-making students are those included, but also the following: developed and intricate plots; unusual treatment of usual situations; rich cultural background; the unbelievable in the common; brief, swift and precise characterisation; humour; irony; glamour; wit; stunning surprise; suspense which keeps you hanging on every word; variety of human emotion, intricacies of human nature; etc. Suggested summing-up by a teacher: with the ironic attitude and moral imperative, the writer seems to say that yes, life is unpredictable and cunning, and full of twists, but there is love and the Hungarian professor, and Colonel Bullfrog, and Christina Rosenthal and her husband; the lonely homeless cat does find a friend and a home; some businessmen are honest; it can be rare, overdone, burnt, a la point, though seldom – 25%! But if we try hard, we’ll succeed and we might not just see light at the end of the tunnel, but even the first miracle! (It’s a word play based on the characters and titles.) Jeffrey Archer (1940 –) And His Place in Modern British Genre Fiction. A Few Peculiarities of Modern British Mainstream Literature J. Archer is now the first name in the best-selling British authors lists, and not only alphabetically: his books are truly a memorable read, being well-written, they keep you hanging on every word. In all his novels and stories he creates an enticing world of glamour, wit, and stunning surprise. He does marvellous work at storytelling. Many literary critics and analysts of today’s literary climate refer J. Archer’s books to the so-called “genre fiction – written to prototypical formulations of plot and subject” (The Twentieth Century Literature In English, London, 1999). Genre fiction is not a product of the 20th century, but nowadays in Great Britain there is a boom in its popularity. Perhaps it is a universal tendency. It is actually a social phenomenon connected with the general disappointment in the high-brow and overly sophisticated literature which came after World War II. It was a turn towards common sense realism, towards the real world, where the character should not only look into himself (J. Joyce, V. Woolf, D. H. Lawrence...), but watch the world and himself in it. Now it seems not so important to shock to keep attention, but rather to make the reader think about human behaviour and relationships: “You should try to be a good person in dark times.” They often repeat the motto “to instruct in morals while it amuses” (A. Trollope about W.M. Thackeray). Such books are not merely entertaining; many present distinguished writing. They get high literary awards and are praised by critics. The broken standards and faded values in 20th century society are reflected in literature and bring about the moral imperative and ironic attitude to human nature and to the world. After the 1980s, when we lost such outstanding writers as W. Golding, G. Greene, M. Spark, K. Amis, A. Burgess there came new names. Among the most well-known men of letters of the 1990s in Great Britain are: J. Archer, B. Bradford, A. Byatt, F. Forsyte, R. Ludlum, T. Pratchet, J. Coetze, M. Bradbury, S. Naipaul, S. Rushdie, K. Ishigura, D. Malouf, J. Bames, F. Weldon, S. Hill, and P. Ackroyd, et al. J. Archer seems to be the one to brilliantly develop the traditions of W. S. Maugham, O’Henry, A. Hailey, R. Dahl, and P. G. Wodehouse. If we use the definition of genre fiction, we could try and derive the “Archerian formula”: a highly eventful plot; perfect knowledge of the subject; a sense of place; “a twist in the tale” and “red herrings”; the reverse and surprise endings; the romantic element, but the lack of sentimentality; irony; the themes of human conduct under pressure; of false and real values; the play of luck, the game of chance, and the acceptance of fate; circular composition; true-to-life characters, not idealised; etc. Несомненно, представленные здесь материалы имеют практическую ценность и могут быть использованы как источник информации при реализации проектной деятельности. Но наша задача не только продемонстрировать вам работу на проектом, но и научить школьников грамотно писать эссе как на английском, так и на русском языках. Сегодня вам предлагаются рекомендации по написанию эссе на русском языке. Это конкурсное задание и оно должно быть представлено в электронном виде не позднее 25 октября 2011 года. К 15 мая на сайте РСМО учителей иностранных языков будет размещены рекомендации по написанию разных типов эссе на английском языке и будут даны конкретные темы. Срок сдачи эссе на английском языке тот же, 25 октября 2011. Желаем успехов и до встречи в ноябре 2011 года, где мы подведем итоги этого долгосрочного проекта и наградим победителей. В период между нашими встречами вы можете обращаться к нам или к нашим зарубежным коллегам с любыми вопросами. Мы постараемся дать исчерпывающие ответы на них.