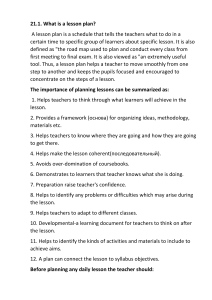

МИНИСТЕРСТВО НАРОДНОГО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ РЕСПУБЛИКИ УЗБЕКИСТАН НУКУССКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ ПЕДАГОГИЧЕСКИЙ ИНСТИТУТ ИМЕНИ АЖИНИЯЗА ФИЛОЛОГИЧЕСКИЙ ФАКУЛЬТЕТ КАФЕДРА АНГЛИЙСКОГО ЯЗЫКА И ЛИТЕРАТУРЫ ВЫПУСКНАЯ КВАЛИФИКАЦИОННАЯ РАБОТА на тему: «РАЗВИТИЕ НАВЫКОВ ЧТЕНИЯ В ОБУЧЕНИИ АНГЛИЙСКОМУ ЯЗЫКУ» Выполнил: студент 4 «Г» курса Кыстаубаев Н.А. Научный руководитель: доцент КГУ, к.ф.н. Кубейсинова Д.Т. Рецензент: старший преподаватель Бабаджанова К.И. Выпускная-квалификационная работа допускается к защите. Протокол № _____ «____» __________ 2014 г. НУКУС-2014 1 MINISTRY OF PUBLIC EDUCATION OF THE REPUBLIC UZBEKISTAN NUKUS STATE PEDAGOGICAL INSTITUTE NAMED AFTER AJINIYAZ PHILOLOGICAL FACULTY DEPARTMENT OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE QUALIFICATION PAPER on the theme: «DEVELOPMENT OF PUPILS’ READING SKILLS IN TEACHING ENGLISH» Fulfilled: the 4th year student Kistaubaev N.A. Scientific adviser: docent of KSU candidate of philological sciences Kubeysinova D.T. Reviewer: senior teacher Babajanova K.I. The Qualification Paper is admitted to the defence. Protocol № _____ «____» __________ 2013 . NUKUS-2013 2 Contents INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………..........…….. 4 CHAPTER I. APPROACHES TO TEACHING READING SKILLS…...........… 7 1.1. Developing reading skills and strategies…………………………….........… 13 1.2. Stages of conducting reading and reading activities……………….........….. 17 1.2.1. Pre-reading…………………………………………………….......……… 18 1.2.2. While-reading…………………………………………………….......…… 20 1.2.3. Post-reading……………………………………………………........…….. 22 1.2.4. Testing reading………………………………………………….......…….. 24 CHAPTER II. METHODS OF TEACHING READING TO LEARNERS.......…31 2.1. The Alphabetic Method………………………………………………….......32 2.2. The Phonic Method…………………………………………………….....….33 2.3. The Word Method…………………………………………………….....…...36 2.4. The Phrase Method…………………………………………………….....…..39 2.5. The Sentence Method……………………………………………………........ 2.6. The Story Method. The Peculiarities of Reading Comprehension….......……40 2.7. Approaches to Correcting Mistakes……………………………….....………41 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………...………43 REFERENCES…………………………………………………………...……….47 APPENDIX……………………………………………………………..………...50 3 Introduction Effective reading is essential for success in acquiring a second language. After all, reading is the basis of instruction in all aspects of language learning: using textbooks for language courses, writing, revising, developing vocabulary, acquiring grammar, editing, and using computer-assisted language learning programs. Reading instruction, therefore, is an essential component of every second-language curriculum [6; 1]. Moreover, according to Dr. West, reading should be given more priority in the teaching process. He emphasizes that reading indicates knowledge of a language, enhances experiences, facilitates the intellectual development of the learner [26; 2]. The challenge of teaching reading to beginning-level adults can be daunting, however, teaching at the beginning level it is also the most rewarding. It is extremely moving to witness an adult who, after years of struggling with the sounds of individual letters, is able to read a letter from a family member or a note that his or her child brings home from school [24; 4]. Learners learn differently, in different ways, and at different rates. Thus, in learning to read, some children need a little more of one thing while others need a bit more of another thing. Trying to push all learners through the same reading program will result in the slowed growth of some and the frustration of others [15; 17]. At the early stages it is important to make the task of learning to read as easy and interesting as possible. Pupils need a lot of practice before they are able to recognize words and phrases quickly, and even the most interesting reading book or textbook, gets boring if they have to read the same thing more than once [23; 151]. Learners of a foreign language, especially at elementary and intermediate levels, are rarely efficient readers in the foreign language. This has to do not only with deficiencies in linguistic knowledge, but also with the strategies employed in reading [21; 1]. On December 10, 2012 President of the Republic of Uzbekistan Islam Karimov signed a decree “On measures to further improve foreign language learning system”. Analysis of the current system of organizing language learning 4 shows that learning standards, curricula and textbooks do not fully meet the current requirements, particularly in the use of advanced information and media technologies. Education is mainly conducted in traditional methods. Further development of a continuum of foreign languages learning at all levels of education; improving skills of teachers and provision of modern teaching materials are required [1]. According to the decree, starting from 2013/2014 school year foreign languages, mainly English, gradually throughout the country will be taught from the first year of schooling in the form of lesson-games and speaking games, continuing to learning the alphabet, reading and spelling in the second year. The topicality of the research work consists in: the researching approaches towards teaching reading at all levels; establishing a new critical view at the methods of teaching reading; discussing reading skills from the perspective of elementary level; figuring out ways of proper error correction strategies; The subject of this qualification paper is shaped around the approaches towards teaching speaking to learners. Developing reading skills and methods of teaching reading form the object of the present work. The purpose of the work is to conduct the overview of the main teaching methods of developing reading skills with second language learners. The following objectives have been settled so that to achieve this purpose: to define principles of developing reading skills; to study the approaches to teaching reading skills at any level; to find out the skills required for an elementary learner to became a proficient reader; to suggest conditions for effective teaching reading; to enumerate the principles behind the teaching reading; to analyze the methods of teaching reading at the elementary level; to reveal the peculiarities of reading comprehension; 5 to identify ways of introducing new vocabulary to learners; to explore approaches to correcting mistakes. The theoretical value of this qualification paper lies in the analysis of teaching reading methods at the elementary level as a methodological problem and in the conducting overview of the reading process nature. The material of the present work may be applicable at the general courses on Methodology of English Teaching. Moreover, it may be highly useful for elaboration of programs and classes on teaching reading at all levels. In addition, it may serve as a basis for further research what illustrates the practical value of the qualification paper. The structure of the research is the following: introduction, two main chapters, conclusion, the list of references and appendix. Introduction states the topicality of the issue, the purpose and objectives of the research, defines the object and the subject of the qualification paper, enumerates methods applied in the process of research, expounds its practical and theoretical value and lays out the structure of the work. Chapter I outlines approaches towards teaching reading skills. In this chapter there are analyzed the facts the more students read, the better they get at reading and we suggest that reading is good for language acquisition in general, provides good models for future writing and offers opportunities for language study. In chapter II we characterize the main methods of teaching reading to learners and analyze peculiarities of teaching reading at the elementary level and suggest several approaches towards correcting mistakes. Conclusion generalizes the results of the research and summarizes all the information provided in the qualification paper. List of references comprises bibliography of literature used during the research. Appendix enumerates possible reading skills that pupils may master in the course of learning and it lists a number of reading possibilities. 6 CHAPTER I. APPROACHES TO TEACHING READING SKILLS Reading skills are the cognitive processes that a reader uses in making sense of a text. For fluent readers, most of the reading skills are employed unconsciously and automatically. When confronted with a challenging text, fluent readers apply these skills consciously and strategically in order to comprehend [6; 4]. There are numerous reading skills that pupils need to master to become proficient readers: extracting main ideas, reading for specific information, understanding text organization, predicting, checking comprehension, inferring, dealing with unfamiliar words, linking ideas, understanding complex sentences, understanding writer's style and writing summaries [27; 2]. But if adult learners are psychologically prepared for reading and the matter is only in acquiring basic reading skills, enriching vocabulary stock and mastering at least few grammar rules, then the situation with young elementary readers is quite different. Learners read effectively only when they are ready. The reader's preparedness to read is called `reading readiness'. According to Thorndike's law of learning, the first requisite for beginning reading is an interest in reading. Reading stories, allowing children to draw and read charts, displaying readable messages, providing picture books and labeling the objects will stimulate their interests [27; 5]. At any level, the following skills are necessary for a pupil to become a proficient reader: automatic, rapid letter recognition; automatic, rapid word recognition; the ability to use context as an aid to comprehension; the ability to use context when necessary as a conscious aid to word recognition [13; 2-3]. A good readiness program develops proficiency in the following area: speaking and listening skill; 7 visual discrimination; knowing the alphabet; thinking skills; word meaning skills; auditory discrimination; moving left to right; sight vocabulary; identification skill. For visual discrimination a teacher may use exercises of identification of the same picture in a row, for visual and auditory discrimination one may find useful exercises of identification of same letters in a row, finding the odd one, picking out word pairs (yes-yes, tit-tit), circling the odd word pair in a group. To train word identification and word recognition tasks like `complete the letters or words with the help of pictures in a sentence' may be appropriate [27; 5]. While teaching reading the following approaches should not be neglected: 1. Focus on one skill at a time. 2. Explain the purpose of working on this skill, and convince the pupils of its importance in reading effectively. 3. Work on an example of using the skill with the whole class. Explain your thinking aloud as you do the exercise. 4. Assign pupils to work in pairs on an exercise where they practice using the same skill. Require them to explain their thinking to each other as they work. 5. Discuss pupils' answers with the whole class. Ask them to explain how they got their answers. Encourage polite disagreement, and require explanations of any differences in their answers. 6. In the same class, and also in the next few classes, assign individuals to work on more exercises that focus on the same skill with increasing complexity. Instruct pupils to work in pairs whenever feasible. 8 7. Ask individual pupils to complete an exercise using the skill to check their own ability and confidence in using it. 8. In future lessons, lead the pupils to apply the skill, as well as previously mastered skills, to a variety of texts [6; 4]. Reading becomes effective when teacher starts with words that are familiar to pupils, uses simple structures, blackboard and flashcards, and gives emphasis to recognizing and understanding the meaning of a word simultaneously. As far as young elementary learners are concerned teaching reading should be started when a child can learn his/her own mother-tongue [27; 9]. Also, it is suggested to use some kind of reading repetition or practice and progress monitoring [16; 151]. Moreover, teachers should always keep in mind the various problems of reading a foreign language. It is useful to know if a pupil can read nonsense words such as `flep, tridding and pertolic' as the ability to read nonsense words depends on rapid and accurate association of sounds with symbols. Good readers do this easily so they can decipher new words and attend to the meaning of the passage. Poor readers usually are slower and make more mistakes in sounding out words. Their comprehension suffers as a consequence. Poor readers improve if they are taught in an organized, systematic manner how to decipher the spelling code and sound words out [29; 19]. There are also several principles behind the teaching of reading: Principle 1: Encourage pupils to read as often and as much as possible. The more pupils read, the better. Everything teachers do should encourage pupils to read extensively as well as – if not more than – intensively. Reading is not a passive skill. Reading is an incredibly active occupation. To do it successfully, we have to understand what the words mean, see the pictures the words are painting, understand the arguments, and work out if we agree with them. If we do not do these things - and if pupils do not do these things - then we only just scratch the surface of the text and we quickly forget it. 9 Principle 2: Pupils need to be engaged with what they are reading. Outside normal lesson time, when pupils are reading extensively, they should be involved in joyful reading – that is teachers should try to help them get as much pleasure from it as possible. But during lessons teachers will do their best to ensure that they are engaged with the topic of a reading text and the activities they are asked to do while dealing with it. As with everything else in lessons, pupils who are not engaged with the reading text - not actively interested in what they are doing - are less likely to benefit from it. When they are really fired up by the topic or the task, they get much more from what is in front of them. Principle 3: Encourage pupils to respond to the content of a reading text not just concentrate on its construction. Of course, it is important for pupils to study reading texts in class in order to find out such things as the way they use language, the number of paragraphs they contain and how many times they use relative clauses. But the meaning, the message of the text, is just as important and we must give pupils a chance to respond to that message in some way. It is especially important that they should be allowed to express their feelings about the topic - thus provoking personal engagement with it and the language. Principle 4: Prediction is a major factor in reading. When we read texts in our own language, we frequently have a good idea of the content before we actually read. Book covers give us a hint of what's in the book, photographs and headlines hint at what articles are about and reports look like reports before we read a single word. The moment we get this hint - the book cover, the headline, the word-processed page - our brain starts predicting what we are going to read. Expectations are set up and the active process of reading is ready to begin. Teachers should give pupils 'hints' so that they can predict what's coming too. It will make them better and more engaged readers. Principle 5: Match the task to the topic when using intensive reading texts. We could give pupils Hamlet's famous soliloquy 'To be or not to be' and ask them to say how many times the infinitive is used. We could give them a restaurant menu and ask them to list the ingredients alphabetically. There might be reasons 10 for both tasks, but, on the face of it, they look a bit silly. We will probably be more interested in what Hamlet means and what the menu foods actually are. Once a decision has been taken about what reading text the pupils are going to read, we need to choose good reading tasks - the right kind of questions, engaging and useful puzzles etc. The most interesting text can be undermined by asking boring and inappropriate questions; the most commonplace passage can be made really exciting with imaginative and challenging tasks. Principle 6: Good teachers exploit reading texts to the full. Any reading text is full of sentences, words, ideas, descriptions etc. It doesn't make sense just to get pupils to read it and then drop it to move on to something else. Good teachers integrate the reading text into interesting class sequences, using the topic for discussion and further tasks, using the language for Study and later Activation [11; 101]. All things considered, reading is far from being a passive skill. Pupils need to be engaged with what they are reading. Teachers should match tasks to the topic, choose activities up to the pupils' abilities and develop teaching programs in such a way so that to develop all the reading skills. Reading is the basic foundation on which academic skills of an individual are built. Many believe that reading is an apt measure of a person’s success in academics. Most of the subjects taught to us are based on a simple concept - read, synthesize, analyze, and process information. Although a priceless activity, the importance of reading has been deteriorating rapidly. Learning to read is an important educational goal. For both children and adults, the ability to read opens up new worlds and opportunities. It enables us to gain new knowledge, enjoy literature, and do everyday things that are part and parcel of modern life, such as, reading the newspapers, job listings, instruction manuals, maps and so on. A reader reads a text to understand its meaning, as well as to put that understanding to use; to find out some information, to be entertained. The purpose for reading is closely connected to a person's motivation for reading. It will also 11 affect the way a book is read. We read a dictionary in a different way from the way we read a novel. The teachers need to be aware of their pupils' learning needs, including their motivation for reading and the purpose that reading has in their lives. It is often difficult to convince pupils of English as a foreign language that texts in English can be understood even though there are vocabulary items and structures that the pupils have never seen before. Skills such as extracting specific information can be satisfactorily performed even though the pupils do not understand the whole text; the same is true for pupils who want to `get the general idea' of a text [11; 191]. It is consider vitally important to train pupils in these skills since they ma y well have to comprehend reading in just such a situation in real life. The underlying purpose of reading is to develop your thoughts, to weave new ideas and information into the understanding you already have and to give new angles to your thinking. If you try to pass this thinking process, you are not really learning as you read. Learning is to do with changing your ideas, combining them together in new ways and extending them to cover new ground. Reading a text is one way in which you trigger off these changes. The purpose of reading is not to have a lot of words pass in front of your eyes, nor to add a few new items to a long `list' of information in your mind. It is to engage your ideas and make you rethink them, make the proper conclusions [21; 34]. Researches have shown that reading is only incidentally visual. More information is contributed by the reader than by the print on the page. That is, “readers understand what they read because they are able to take the stimulus beyond its graphic representation and assign its membership to appropriate group of concepts already stored in their memories” [25; 134]. Skills in reading depend on the efficient interaction between linguistic knowledge and knowledge of the world. Reading texts also provides opportunities to study language: vocabulary, grammar, punctuation, models for English writing. 12 1.1. Developing reading skills and strategies Reading is not an instinctive human ability such as speaking. Reading is a recent development in the history of the human race. Not every society reads. Humans have not evolved in a way that there is a reading center in the brain [23,10]. In order to read, we have to adapt or train our brain to perform in ways it was not naturally designed to work. Nevertheless, oral and written language have much in common. Both are based on the same lexical, grammatical, syntactical and textual rules. The first thing that beginning readers have to experience is that written material is a representation of knowledge they already have, in other words, they have to learn to see the relation between meaning and print. However, while oral language usually is acquired without formal instruction, most children need explicit instruction in the process of learning to read. 1. children have to develop the awareness that words are made up of sounds. 2. they have to develop the awareness that print represents these sounds. 3. they have to develop the understanding that the letters on the page represent these units of sound. Once they have reached this level of phonological awareness, they are ready to learn to read. For some children this is very difficult. The code-breaking strategy of identifying phonemes as units in the alphabetic code in particular, seems to be problematic for beginning readers because these phonemes can hardly be perceived as speech. In addition to being able to break up spoken words into smaller units and to understand that letters represent sounds, children need to have a knowledge base, vocabulary knowledge, metacognition, and motivation. Several models of reading development have been proposed to describe the abilities and phases that characterize reading development. Researchers, for example, distinguished three stages in learning to read words: the logographic stage, the alphabetic stage, and the orthographic stage. 13 In the logographic stage, children mainly use graphic features to read words without insight into the letter-sound correspondence. Children do not really read in this stage, they remember the features of the letter, the word or the logo. In the alphabetic stage, children learn to understand the principle of mapping graphemes onto phonemes to be able to decode both known and unknown words. Crucial is this stage is phonological awareness or the awareness of the fact that speech can be divided in smaller units such as syllables and phonemes. The orthographic stage distinguishes itself from the alphabetic stage by operating with bigger units, making use of spelling patterns, and being nonphonological. Advanced pupils who are literate in their own language sometimes are “left to their own devices” when it comes to teaching them reading skills. They will simply learn good reading by absorption. In reality, there is much to be gained by focusing on reading skills. It is generally recognized that the efficient reader versed in ways of interacting with various types of texts, is flexible, and chooses appropriate reading strategies depending on a particular text in question. The reader has to match reading skill to reading purpose. We can differ between reading aloud and silent reading. Reading aloud is not appropriate for advanced pupils. We can use it when we have control reading. At the advanced level the most suitable is silent reading. Sustained silent reading allows pupils to develop a sense of fluency. Also silent reading can help the pupils to increase the speed of their reading. Reading speed is usually not much of an issue for all but the most advanced pupils. If teachers are teaching beginning level students, this particular strategy will not apply because they are still struggling with the control of a limited vocabulary and grammatical patterns. Intermediate-to-advanced level students need not be speed readers, but we can help them increase reading rate and comprehension efficiency by teaching a few silent reading rules: • You don't need to "pronounce" each word to yourself. • Try to visually perceive more than one word at a time, preferably phrases. 14 • Unless a word is absolutely crucial to global understanding, skip over it and try to infer its meaning from its context. Aside from these fundamental guidelines, which if followed can help learners to be efficient readers, reading speed is usually not much of an issue for all but the most advanced learners. Academic reading, for example, is something most learners manage to accomplish by allocating whatever time they personally need in order to complete the material. If students can read 250 to 300 words per minute, further concern over speed may not be necessary. It is now generally accepted that reading is not the careful recognition and comprehension of each word on the page in sequence. A good reader use a minimum of `clues' from the text to reconstruct the writer's message. It is not difficult for the fluent reader to read the text with missing words. Experiments have shown that sometimes readers are not even aware of these things. Their successful reading depends upon their ability to predict what comes next. We read, in sense, what we expect to read, using our knowledge of language and our knowledge of the topic to predict to a large degree what comes next and so move on quickly. Fluent advanced readers possess many different skills which they apply actively to the reading of the text: they predict from syntactic and semantic clues the words; they read in phrases, not in single words and actually skip over words if these are not needed for general understanding; they learn to read `between the lines' and working on the meaning of the text at different levels, understanding information, making inferences and critically evaluating ideas; they guess the meaning of new words from contextual clues or by applying knowledge of how words can be formed from others; they follow meaning through the paragraph by recognizing signals like `however' and `on the other hand' and by understanding how words 15 and phrases like `it', `this', `the latter' and `these matters' refer back to something earlier in the text [23; 128]. “Successful reading depends on the interaction of reading `strategies' for `processing' the text, background knowledge and linguistic competence” [23; 57]. Silent reading may be subcategorized into intensive and extensive reading. We need to make a distinction between extensive and intensive reading. The term “extensive reading” refers to reading which students do often away from the classroom. They may read novels, web pages, newspapers, magazines or any other reference material. Where possible, extensive reading should involve reading for pleasure – what Richard Day calls joyful reading [9; 104]. This is enhanced if students have a chance to choose what they want to read, if they are encouraged to read by the teacher, and if some opportunity is given for them to share their reading experiences. Although not all students are equally keen on this kind of reading, we can say with certainty that the ones who read most progress fastest. Thus, all pleasure reading is extensive. Technical, scientific, and professional reading can also be extensive. Extensive reading is carried out to achieve a general understanding of a usually somewhat longer text (book, long article, essay, etc.). Most extensive reading is performed outside of class time. Pleasure reading is often extensive. Technical, scientific, and professional reading can, under certain special circumstances, be extensive when one is simply striving for global or general meaning from longer passages. By stimulating reading for enjoyment or reading where all concepts, names, dates, and other details need not be retained, students gain an appreciation for the affective and cognitive window of reading: an entree into new worlds. Extensive reading can sometimes help learners get away from their tendency to overanalyze or look up words they don't know, and read for understanding. The term “intensive reading”, on other hand. refers to the detailed focus on the construction of reading texts which takes place usually (but not always) in classrooms. Teachers may ask students to look at extracts from magazines, poems, 16 Internet websites, novels, newspapers, plays and a wide range of other text genres. The exact choice of genres and topics may be determined by the specific purposes that students are studying for (such as business, science or nursing). In such cases, we may well want to concentrate on texts within their specialities. Intensive reading is usually accompanied by study activities. We may ask students to work out what kind of text they are reading, tease out details of meaning, look at particular uses of grammar and vocabulary, and then use the information in the text to move on to other learning activities. We will also encourage them to reflect on different reading skills. Intensive reading is usually a classroom-oriented activity in which pupils focus on the linguistic or semantic details of a passage. Intensive reading calls pupils attention to grammatical forms, discourse markers, and other surface structure details, for the purpose of understanding literal meaning, implication, rhetorical relationships. Intensive reading practiced in class needs to be complemented by extensive reading in or out of class. It is important to be sure that pupils have ample time for extensive reading. Only then pupils are given the opportunity to operate strategies like prediction or guessing word meaning and to develop the ability to follow the lines of argument. It is carried out to achieve a general understanding of a text. The idea that some words in the text may be skipped or ignored will certainly seem strange to pupils accustomed to plodding word by word; but the techniques of skimming and scanning require this [22, p.34]. These terms are sometimes used indiscriminately, but we will distinguish them below. Skimming consists of quickly running one's eyes across the whole text (such as an essay, article, or chapter) to get the gist. It gives the learners the advantage of being able to predict the purpose of the passage, the main topic, or message, and possibly some of developing or supporting ideas. This gives them a `head start' as they embark on more focused reading. The students need to be able to skim a text – as if they were casting their eyes over its surface – to get a general idea of what it is about (as, for example, when we run our eyes over a film review to see 17 what the film is about and what the reviewer thought about it, or when we look quickly at a report to get a feel for the topic and what its conclusions are). Scanning is quickly searching for some particular piece or pieces of information in a text. Scanning exercises may ask pupils to look for names or dates, to find the definition of some concept. The purpose of scanning is to extract certain specific information without reading through the whole text. The students also need to be able to scan the text for particular bits of information they are searching for (as, for example, when we look for a telephone number, what’s on television at a certain time or search quickly through an article looking for a name or other detail). This skill means that they do not have to read every word and line; on the contrary, such an approach would stop them scanning successfully. Skimming and scanning are useful skills. They do not remove the need for careful reading, but they enable a reader to select the texts, or the portions of the text, that are worth spending time on. The strategy of semantic mapping or grouping the ideas into meaningful cluster, helps the reader to provide some order to the chaos. Making such semantic maps can be done individually, but they make for the productive group work technique as pupils collectively induce order and hierarchy to the passage. Guessing strategy is very broad on meaning. The pupils may guess the meaning of a word, the grammatical or discourse relationships, cultural references. “Pupils should utilize all their skills and put forth as much efforts as possible to be on target with their hypothesis”. The key to the successful guessing is to make it reasonably accurate. We can help them to become accurate guessers by encouraging them to use effective comprehension strategies in which they fill gaps in their competence by intelligent attempts to use whatever clues are available to them. Language based clues included word analysis, word associations, and textual structure. Reading for detailed comprehension, whether this entails looking for detailed information or picking out particular examples of language use, should be seen by students as something very different from the skills mentioned above. 18 Many students are perfectly capable of doing all these things in other languages, of course, though some may not read much at all in their daily lives. For both types of student, we should do our best to offer a mixture of materials and activities so that they can practise using these various skills with English text. 1.2. Stages of conducting reading and reading activities Reading can be subdivided into three stages: pre-reading, while reading and post-reading. As was admitted by Hedge T. “People reading in foreign language often need to be given support before they begin reading, an introduction which motivates reading by creating interest in the topic and which facilitates reading by developing background understanding and linguistic knowledge” [Hedge 1998:96]. 1.2.1. Pre-reading There are various things we can do before reading a text which will make it easier for pupils to understand the text and help them focus attention to it as they read. They include: presenting some of the new words which will appear in the text; giving a brief introduction to the text; giving one or two `guiding' question (orally or on the board) for pupils to think about as they read; suggest them to read the title of the text and try to guess what it is about. We do not need to present all the new words in the text before the pupils read it; they may guess the meaning of the words from the context. An important part of reading is being able to guess the meaning of unknown words, and we can help pupils to develop their reading by giving them practice in this. It is important to introduce the theme of the text before we ask them to read it. This serves two purposes: to help pupils in their reading, by giving them some idea what to expect; 19 to increase their interest and so make them want to read the text [4; 69]. One way to introduce the text is just to give the simple sentence. For example: “We are going to read about fossils. The text tells us how animals and plants become fossils.” Another more interesting way of discussion, to start pupils thinking about the topic: “Do you know how the fossils are formed? Where do they come from? Have you ever seen the fossils? What was it like?”. It is important to mention that the teacher should not say too much when introducing the text, because it may kill the pupils' interest instead of arousing it [8; 60]. Before reading the text the teacher may give the pupils some guiding questions. Guiding questions should be concerned with the general meaning or with the most important points of a text, and not focus on minor details; they should be fairly easy to answer and not too long. For example: Very few animals become fossils. Why? What kind of fossils are found in caves? How do animals become fossils? [8; 61] Different types of activities can be applied to prepare the pupil to reading the suggested text: I. 1) Read the text and try to understand the general meaning of the story. (All the words which are highlighted are nonsense words). A country girl was walking along the snerd with a roggle of milk on her head. She began saying to herself, “The money for which I will sell this milk will make me enough money to increase my trund of eggs to three hundred. These eggs will produce the same number of chickens, and I will be able to sell the chickens and for a large wonk of money. [8; 60] 2) Now look at the highlighted words again and try to guess what they might mean? (The actual words are: road, can, stock, sum). II. 1) Discuss in small groups or in pairs the picture of earthquake from the text or the title. Where it might be, what seems to have happened? 2) Do the tasks below before reading the text: 20 Write down at least five questions, which you hope the text will answer. Try to imagine what text will tell you about: buildings, people, hills around the city, the land and the sea... Here are some words and phrases from the text. Can you guess how they are used in the text? (the sea-bed, the Richter scale, a huge wave, tremors, massive shock) 3) Now read the text . III. Before you read the text, read the questions below and try to answer them. After reading the text read once more the questions and try to correct the mistakes which you have done before the reading. IV. Read the second or the third paragraph and try to predict what you are going to read in the first and last paragraph. 1.2.2. While-reading Not all reading is simple extensive-global reading. There may be certain facts or rhetorical devices that pupils should take note while they read. This gives them a sense of purpose rather than just reading. It is important to inform the pupils why they are going to read the suggested text. You may supply them with exercises which they should do, or explain what you will do when they continue reading. Then they will be able to choose the right strategy for the reading. We can distinguish between different aims of the reading: Reading for the main idea. This means to read the whole text quickly to get the general idea of what it is about. Read text predictions. At points in the text that something dramatic has happened, or is going to happen soon, we can ask pupils to stop reading, close the books and try to predict what might happen next. This encourage the pupils to read carefully, imagine and discuss future possibilities, then read the next part to check their predictions [21; 67]. 21 Reading to extract specific information. Pupils are supplied with the questions or task which they are going to answer before reading the text. This type of reading will help them to develop their scanning skills. They should quickly scan the text only to extract the information which the questions demand. Reading for communicative tasks. This type of reading is very important, because it helps to develop not only pupil's reading skills, but also their communicative skills. For this purpose you may cut the short text into pieces. Then divide the pupils in two groups. Then give the part of the text to each pupils. They should put them together in the right order and read the whole story. Then the teacher may ask the questions concerning the story, or ask the pupils their opinion about the events in the story. The reading here is proposal and communicative. Those who read know that they will have to answer some questions in order to communicate [12; 204]. This type of reading is usually supplied with different activities: I. For each paragraph or part of the story, pupils find the words or the sentences, that are the most important. This encourages them to not read the whole text in details. II. Read the text and note down the most important information about the main hero in the form of the table or the chart. Then compare this information with the information that your partner put down. Discuss the criteria which you use while choosing the information. III. Before the pupils start reading the text they are supplied with questions, true or false statements, multiple-choice items or matching items. They should read the text and find the right answer for the tasks. It is as important in reading as it is in listening to be able to accurately assess students' comprehension and development of skills. Consider some of the following overt responses that indicate comprehension: 1. Doing—the learner responds physically to a command. 22 2. Choosing—the learner selects from alternatives posed orally or in writing. 3- Transferring—the learner summarizes orally what is read. 4. Answering—the learner answers questions about the passage. 5. Condensing—the learner outlines or takes notes on a passage. 6. Extending—the learner provides an ending to a story. 7. Duplicating—the learner translates the message into the native language or copies it (beginning level, for very short passages only). 8. Modeling—the learner puts together a toy, for example, after reading directions for assembly. 9. Conversing—the reader engages in a conversation that indicates appropriate processing of information. 1.2.3. Post - reading Comprehension questions are just one form of activity appropriate for postreading. Consider vocabulary study, identifying the author's purpose, discussing the author's line of reasoning, examining grammatical structure, or steering pupils toward a follow-up written activity. The activities which are given to pupils after reading the text are generated by the text and extend its potential for meaningful language work. The tasks can not be performed without the text, that is, they cannot replace the text. Frequently, they involve the pupils in detailed revision of the text, which will help them to understand the text better [11; 99]. After reading the given text pupils may do the following activities: I. Do the multiple-choice exercise, and choose the answers which better confirm the statements, explain them or support the ideas. II. Summarize the text and make a conclusion. Discuss in pairs the main idea of the text. III. Guess the meaning of new words from the context in the sentence. Match the words with the meanings. Then make your own sentences with this new words. IV. Write your own ending of the story, or write your own composition on the same topic. 23 Here we suggest an extract from an ESL textbook designed to teach reading skills. In this case, of course, the three skills are implied in the unfolding of the lesson. The extract “Rain Forests”, is designed for beginners (Boone, Bennett, & Motai, 1988, p.14-15). It illustrates the use of natural, authentic language and tasks at the beginning level. Some attention is given to bottom-up skills, but not at the expense of top-down processing, even at this level. RAIN FORESTS by Scott Adelson Have you ever seen a rain forest? Where do rain forests grow? What is unusual or unique about rain forests? Are they important to the world? This text is about special forests in tropical areas of the world that are being cut down, and about a special group that is trying to save them. In many tropical countries, people are cutting down rain forests to make room for farms. They hope that the farms will make money for them so that they can pay their debts. But a new organization is trying to help these countries save their forests. The name of this organization is Conservation International. Conservation International pays countries not to cut down their rain forests. Their first agreement was with Bolivia, for a 4,000,000 acre reserve in the Amazon River basin in northeast Bolivia. The region has savannahs, deep woods, and rain forests. It is famous for the different plants and unusual wildlife that live there. Bolivia and Conservation International will take care of the reserve together. This idea of helping countries make rain forest reserves is so unusual that Brazil and Ecuador, which are both interested in this program, are already having talks with Conservation International. Tasks on the text to develop pupils’ reading skills: 1. Study the vocabulary debt - money you owe to another person organization - group conservation - saving the land and the animals reserve - a safe place for animals and nature 24 basin - valley where there is a river region - area; large place savannah - dry, flat land; plain 2. Understanding the Details Do you understand the text? Try to answer the following questions. You may look in the text. Practice scanning for important words or numbers. Can you do this exercise in five minutes? 1. Why do some tropical countries cut down their rain forests? 2. What is the name of the organization that is helping to save rain forests? 3. What country did they do business with first? 4. How much land did they get for a reserve? 5. Where is the reserve located? 6. Why is this reserve interesting to save? 7. Who will take care of the reserve? 8. What other countries are interested in this program? 3. The Big Picture: Reading for the Main Idea What do you think is the most important idea in this text? a. Small countries need help to save their rain forests. b. Bolivia is taking care of its rain forests in the Amazon River basin. c. Conservation groups are trying to help tropical countries save their rain forests. 4. Discuss. What Do You Think? Are people in your country worried about conservation? Do you think it is a good idea to pay countries not to cut down their forests? What do you think is the most important conservation problem? Thus, we suggest effective techniques for developing pupils’ reading skills and try to describe each of them and define their purposes: 25 № Reading techniques 1 Skimming Description and their purposes Reading a passage quickly to grasp the main idea or gist. 2 Scanning Reading a passage quickly to find specific information. 3 Contextual guessing Making guesses about the meaning of words by looking at the surrounding words or situation. 4 Cloze exercise Fill-in-the-blank exercise, in which some words are omitted, designed to measure how well the reader understand how a text is linked together. 5 Outlining Note-taking technique designed to help the reader see the overall organization of a text. 6 Paraphrasing The ability to say or write ideas in other words; measures the reader’s understanding of the main ideas of a text. 7 Scrambled stories Also known as ‘jigsaw reading’: the reader re-orders the mixed up pieces of a text to show he understands how a text fits together. 8 Information transfer Exercise which requires readers to transfer information from the text into another form of related text or drawing (filling in a chart, tracing a route on a map); designed to measure comprehension; 9 Making inferences “Reading between the lines”: the reader understands what is meant but not stated in a passage. 10 Intensive reading Reading carefully for complete, detailed 26 comprehension (main ideas, details, vocabulary). 11 Extensive reading Reading widely in order to improve reading comprehension, reading speed and vocabulary. 12 Passage completion Finishing a reading passage; involves predicting a logical or suitable conclusion based on a thorough understanding of the text 1.2.4. Testing reading There are numerous ways of testing reading comprehension, ranging from multiple-choice items to open-ended questions. Although the multiple-choice items are sometimes the most suitable instrument for testing reading comprehension, they should not be overused. Frequently other items are more interesting and useful. The text itself should always determine the types of questions which are constructed. Certain texts may lead themselves to multiple-choice items, others to true or false items, others to matching items, others to rearranged items, other to open-ended questions. Indeed, sometimes the same text will demand at least two or three different types of items [15; 107]. Multiple-choice tests This task is likely to be the most familiar to the pupils. It consists of a text, which can be of almost any type and genre, accompanied by one or more multiplechoice items. These may be in the form of a series of statements, a question plus answer, or an incomplete statement with a choice of phrases or words with which to complete in. There must be four options, only one of which is correct. It is common to have items corresponding to specific section of the text, but there also may be items to test comprehension of the text as the whole. Supporting tasks: 1. This type of multiple-choice is used for understanding the main idea. For this purpose we can also use matching tasks. 27 What is the writer complaining about in the letter: A. Buses are becoming more crowded. B. Bus stops are poorly maintained. C. Adults can be thoughtless on buses. D. Children should be more polite on buses. The skill here is reading for gist or skimming. Pupils need to read the text through from beginning to end. 2. The task to recognize the writer's attitude and opinion. The answer will not usually be stated explicit at any one point in the text. An appreciation of the writer's attitude or opinion depends on picking up the meaning of adverbs and modal expressions that may be scattered throughout the text. The writer thinks that the companies who advertise on the Internet. A. should be more carefully monitored; B. never sell quality products; C. are more common; D. try to exploit their customers. 3. The task is to recognize the tone. In order to be familiar with the tone, pupils should read the text carefully and pay attention to the details. She comments on this story: A. admiring; B. critical; C. slightly dismissive; D. excited. Multiple-choice test as usual include different types of multiple-choice tasks. True or false statements That is another task type which is familiar to most of the pupils. They are given a text and a list of questions to it. Candidates determine whether the statements are correct or incorrect, according to the text. Sometimes the third option is included (`not given' or `not known'), for case where the text does not give the reader enough information to determine whether a statements true or false. 28 The true or false test, however, has two main disadvantages: firstly it can encourage guessing, since testees have 50 per cent chance of giving correct answer for each item. Secondly, as the base score is 50 per cent and thus the average text difficulty general in the region of 75 per cent, the test may fell to discriminate widely enough among the testees unless there are a lot of items [15; 222]. For example: Read the text and decide whether the statements below are true or false. A typical English breakfast is a very big meal-sausages, bacon, eggs, tomatoes, mushrooms and of course toasts. But nowadays many people don’t have time to eat all this and just have toast, or sometimes fruit and yoghurt. The typical breakfast drink is tea which people have with cold milk. Some people have coffee with just hot water. Many visitors to Britain think this coffee is horrible. For many people lunch is a quick meal. In cities there are a lot of sandwich bars, where office workers can choose the kind of bread they want, either brown or white, and then all sorts of salad and meat or fish to go in the sandwich. Pubs often serve good, cheap food, both hot and cold. School children can have a hot meal at school, but many just take a snack from home – a sandwich, a drink, some fruit and perhaps some crisps. Many British people don’t eat a full breakfast. T/F Many British people choose toast for breakfast. T/F The typical drink with breakfast is coffee. T/F Many visitors to Britain love British coffee. T/F Many offices in cities have sandwich bars. T/F Matching tasks These tasks are used by several of the exam boards, some of which include more than one matching task in the reading tests. In matching tasks the pupils choose from the list of prompts. The prompts may be headings, statements, or question completion. For example, candidates may be asked to match the 29 description to the appropriate paragraph of a text, or to match words or phrases with their meaning. Task 1- match each expression to one of the statements 1. I am not afraid of giving speeches in a. friendly and outgoing front of the class 2. I enjoy going to parties where I b. strong and independent don’t know everyone 3. I avoid expressing my feelings and c. laid-back and relaxed ideas in public 4. I insist on making my own decisions d. kind and generous 5. I don’t mind giving up my time to e. honest and sincere help other people 6. I never worry about getting places f. shy and reserved on time 7. I always feel like going dancing g. wild and crazy 8. I can’t stand being in a messy, h. calm and cool disorganized room 9. I prefer telling people how I feel, i. neat and tidy even if it’s embarrassing Completion items There are two different types of completion the items: 1. consisting of the gaps for completion in the items following the text; 2. consisting of the gaps directly in the text. These tasks of type 2 involve texts from which single words, phrases, sentences or paragraphs have been removed. In some cases pupils have to decide what should fill the gap, while in others they must choose from the series of alternatives, only one of which is correct. Where paragraph or sentences have been removed, there is usually an item among the alternatives that does not belong to the text. In some cases, pupils write in words or figures which are missing from diagram or summary, that accompanies the main text. 30 Rearrangement items This type is particularly useful for testing the ability to understand a sequence of steps in the process or events in a narrative. In the whole in an exercise for classroom practice the pupils will be often required to rewrite the jumbled sentences in the correct sequences. Also pupils may be asked to rearrange the paragraphs of the text in right order. Jumbled text a. Of course, now I can understand it all more clearly. Father and I belonged to widely different generations, held different expectations; a revolution in attitudes to b. opportunities that had been denied him. A neighbor sent me the announcement of his death in the local paper. The funeral was to be the day I received the news. I thought c. I realized; and maybe I could have eventually forgiven him. But would he ever forgiven me? d. women had occurred between his day and him. But at the time all I could feel was bitter resentment, because he was not proud of me but deeply jealous that I had 1.... 2..... 3.... 4... Open-ended questions Pupils are required to answer the questions or continue the statements concerning the text. The answers may include one word or several sentences. There are many ways in which teachers may support pupils in developing the skills measured in reading tests, but it is important to highlight the difference between particular reading activities and the demands of the text. The pupils can ask and answer the questions in pairs. The answers to these questions are not essential for an overview of the text; they are the details which we expect pupils to be able to access on the second reading, not on the first. Thus, the classic principles of classroom assessment apply to our attempts to assess reading comprehension: we should be specific about which micro- or 31 macro-skills we are assessing; identify the genre of written communication that is being evaluated; and choose carefully among the range of possibilities from simply perceiving letters or words all the way to extensive reading. In addition, for assessing reading, some attention should be given to the highly strategic nature of reading comprehension by accounting for which of the many strategies for reading are being examined. Finally, reading assessment implies differentiating bottom-up from top-down tasks, as well as focus on form versus focus on meaning. In our efforts to design tests at any one or a combination of these levels and categories, we should consider the following taxonomy of tasks. These are not meant to be exhaustive, but rather to provide an overview of some possibilities. 1. Perceptive reading (recognition of symbols, letters, words) • reading aloud • copying (reproduce in writing) • multiple-choice recognition (including true-false and fill-in-the-blank) • picture-cued identification 2. Selective reading (focus on morphology, grammar, lexicon) • multiple choice grammar/vocabulary tasks • contextualized multiple choice (within a short paragraph) • sentence-level cloze tasks • matching tasks • grammar/vocabulary editing tasks (multiple choice) • picture-cued tasks (Ss choose among-graphic representations) • gap-filling tasks (e.g., sentence completion) 3. Interactive reading • discourse-level cloze tasks (requiring knowledge of discourse) • reading + comprehension questions • short-answer responses to reading • discourse editing tasks (multiple choice) • scanning 32 • re-ordering sequences of sentences • responding to charts, maps, graphs, diagrams 4. Extensive reading • skimming • summarizing • responding to reading through short essays • note taking, marginal notes, highlighting • outlining This chapter has only begun to scratch the surface of information on the teaching of reading, but we should now have a grasp of some issues surrounding this challenging task, and a sense of how to go about designing effective tasks and activities. 33 CHAPTER II. METHODS OF TEACHING READING TO LEARNERS At an early stage of teaching reading the teacher should read a sentence or a passage to the class himself/herself. When s/he is sure the pupils understand the passage, s/he can set individuals and the class to repeat the sentences after him/her, reading again himself/herself if the pupils' reading is poor. The pupils look into the textbook. In symbols it can be expressed like this: T - C - T - P1 - T - P2 - T - P3 T - C (T - teacher; C - class; P - pupil). This kind of elementary reading practice should be carried on for a limited number of lessons only. When a class has advanced far enough to be ready for more independent reading, reading in chorus might be decreased, but not eliminated: T - C - P1 P2 P3. When the pupils have learned to associate written symbols with the sounds they stand for they should read a sentence or a passage by themselves. In this way they get a chance to make use of their knowledge of the rules of reading. It gives the teacher an opportunity to see whether each of his pupils can read. Symbolically it looks like this: P1 P2 Pn T (S) C (S - speaker, if a tape recorder is used) [20; 184]. All in all, there are six important methods of teaching reading. They are as follows: The alphabetic method or ABC method or spelling method. The phonic method. The word method. The phrase method. The sentence method. The story method [25; 6]. Let us consider them in details. 34 2.1. The Alphabetic Method The teacher teaches the pupils the names of letters in their alphabetic order. S/he also may combine two or more letters to form a word: i - n=in, o - n=on, o –n - e=one. From ‘words’ it moves to ‘phrases’ and finally ‘sentences’. Thus, the procedure begins from letters and ends in sentences. There are many ways to teach the alphabet and all teachers develop their own style over time. One of the common instructions to introduce a new letter is the following one: 1. Hold up an alphabet letter flashcard so all pupils can see it. 2. Chorus the letter 3 to 5 times. Then ask each pupil individually to say the letter. 3. Teach the sound of the letter (e. g. "A is for 'ah'. ah - ah - ah"). Chorus again and check individually. 4. Provide an example of an object that begins with the letter. Double-sided flashcards with the letter on one side and a picture on the other are great for this. (e. g. "What's this?" (elicit "A"). "And A is for.?" (elicit "ah"). "And 'ah' is for. (turning the card over)"apple!". Chorus the word and check individually. 5. Do a final check (T: "What's this?", Ss: "A", T: "And 'A' is for.?", Ss: "ah", T: "And 'ah' is for.?" Ss: "Apple!"). These steps can be followed by 'magic finger', 'pass it', 'find it', 'slow motion' or any other alphabet game. Also, the ABC song is a nice way to start and finish the alphabet segment of your lesson. The pros of alphabetic method are that it gives the pupils sufficient opportunity to see words and helps them to build up the essential visual image. However, as it is a dull and monotonous process it appears to be a difficult and lengthy method that does not expand the eye-span [28; 6]. The letters that occur in both languages, but they are read differently, are the most difficult letters for pupils to retain. Obviously in teaching a pupil to read English words, much more attention should be given to those letters which occur in both languages but symbolize entirely different sounds. For example, H, p. (Pupils often read How as [nau]. Therefore, in presenting a new letter to pupils a teacher 35 should stress its peculiarity not only from the standpoint of the English language (what sound or sounds it symbolizes) but from the point of view of the native language as well [20; 180]. Since the 1960s, solid research has shown that the ability to recognize and name the letters of the alphabet upon entry to school is the best single predictor of reading achievement at the end of the first year of literacy instruction. However, it also shows that simply teaching children the alphabet does not guarantee that they will rapidly develop literacy skills. 2.2. The Phonic Method Beginning pupils do not understand that letters represent the sounds in words, although they do know that print represents spoken messages [22; 19]. Phonological awareness is the strongest predictor of future reading success for children. No research exists that describes the affects of phonological awareness on reading for adults. However, it is believed that teaching phonological awareness to beginning-reading adults improves their reading accuracy and spelling, especially for reading and spelling words with blends. The skill of matching sounds and letter symbols is called phonics. Phonics, involves learning that the graphic letter symbols in our alphabet correspond to speech sounds, and that these symbols and sounds can be blended together to form real words. Word analysis strategies enable pupils to "sound out" words they are unable to recognize by sight. Explicit, direct instruction in phonics has been proven to support beginning reading and spelling growth better than opportunistic attention to phonics while reading, especially for pupils with suspected reading disabilities. Beginning readers should be encouraged to decode unfamiliar words as opposed to reading them by sight, because it requires attention to every letter in sequence from left to right. This helps to fix the letter patterns in the word in a reader's memory. Eventually, these patterns are recognized instantaneously and words appear to be recognized holistically. After first operating at an alphabetic stage, during which elementary learners recognize words using letters or letter groups but not sound-symbol connections, 36 pupils develop their ability to connect the sounds in part of a word with the letter or letters which go with that sound. They become able to use this knowledge in a new context by analogy. Analogical reasoning is very important in this process. It works initially with two phonological units: the first phoneme in a word (often referred to as the ‘onset’); the remainder of the word, the part that rhymes (often referred to as the ‘rime’) [13; 6]. The phonic method is based on teaching the sounds that match letters and groups of letters of the English alphabet. What is important here is that the sounds NOT the names of the letters that are taught. As the sounds that match alphabet letters, the letters are written and illustrated with “key” words to represent the sound. The word is broken into speech sounds. The alphabet may be introduced afterwards. The teacher teaches English through phonetic script, e. g.: Cup-/k/ /4/ /p/ [25; 7]. This phonic method gives the good knowledge of sounds to the learners. It is also linked with speech training and helps to avoid spelling defects. The drawback of the method lies in the facts that meaning is not given priority in this method, words with similar sounds but different spelling confuse the learners. In addition may delay the development of reading words as a whole. At the beginning levels of learning English, one of the difficulties students encounter in learning to read is making the correspondences between spoken and written English. In many cases, learners have become acquainted with oral language and have some difficulty learning English spelling conventions. They may need hints and explanations about certain English orthographic rules and peculiarities. While you can often assume that one-to-one grapheme-phoneme correspondences will be acquired with ease, other relationships might prove difficult. Consider how you might provide hints and pointers on such patterns as these: • "short" vowel sound in VC patterns (bat, him, leg, wish, etc.) • "long" vowel sound in VCe (final silent e) patterns (late, time, bite, etc.) 37 • "long" vowel sound in W patterns (seat, coat, etc.) • distinguishing "hard" c and g from "soft" c and g (cat vs. city, game vs.gem, etc.) Here we suggest micro- and macro-skills for listening comprehension: Micro-skills Discriminate among the distinctive graphemes and orthographic patterns of English. Retain chunks of language of different lengths in short-term memory. Process writing at an efficient rate of speed to suit the purpose. Recognize a core of words, and interpret word order patterns and their significance. Recognize grammatical word classes (nouns, verbs, etc.), systems (e.g., tense, agreement, pluralization), patterns, rules, and elliptical forms. Recognize that a particular meaning may be expressed in different grammatical forms. Macro-skills Recognize cohesive devices in written discourse and their role in signaling the relationship between and among clauses. Recognize the rhetorical forms of written discourse and their significance for interpretation. Recognize the communicative functions of written texts, according to form and purpose. Infer context that is not explicit by using background knowledge. Infer links and connections between events, ideas, etc.; deduce causes and effects; and detect such relations as main idea, supporting idea, new information, given information, generalization, and exemplification. Distinguish between literal and implied meanings. Detect culturally specific references and interpret them in a context of the appropriate cultural schemata. 38 Develop and use a battery of reading strategies such as scanning and skimming, detecting discourse markers, guessing the meaning of words from context, and activating schemata for the interpretation of texts. These and a multitude of other phonics approaches to reading can prove useful for learners at the beginning level and especially useful for teaching children and non-literate adults. 2.3. The Word Method The word method is otherwise known as “Look and Say” Method [25; 7]. The look and say teaching method, also known as the whole word method, was invented in the 1930s and soon became a popular method for teaching reading. By the 1930s and 1940s there was a very strong focus on teaching children to read by this method. In the 1950s, however, it was fiercely criticized in favor of phonicsbased teaching. The debate still continues today. The look and say method teaches children to read words as whole units, rather than breaking the word down into individual letters or groups of letters. Elementary learners are repeatedly told the word name while being shown the printed word, perhaps accompanied by a picture or within a meaningful context. By pointing at each word as a teacher reads sentences, children will start to learn each word. The teaching principles of the discussed method are as follows: New words are systematically introduced to a pupil by letting him/her see the word, hear the word and see a picture or a sentence referring to the word. Flashcards are often used with individual words written on them, sometimes with an accompanying picture. They are shown repetitively to a child until he memorizes the pattern of the word. Progressive texts are used with strictly controlled vocabularies containing just those words which have been learned. Initially an elementary learner may concentrate on learning a few hundred words. Once these are mastered new words are systematically 39 added to the repertoire. Typically a child would learn to recognize 1,500 to 3,000 words in his first three or four years of school. Pupils should also learn the reading of some monosyllabic words which are homophones. For example: son - sun; tail - tale; too - two; write - right; eye-I, etc. It is advised to use flashcards to encourage young elementary learners to read, such techniques may be suggested: (1) pupils choose words which are not read according to the rule. For example: lake, plane, have, Mike, give, nine; (2) pupils are invited to read the words which they usually misread: yet - let cold - could form - from come - some called - cold wood - would does - goes walk - work (3) pupils are invited to look at the words and name the letter (letters) which makes the words different: though - thought through - though since - science with - which hear - near content - context hear - hare country - county (4) pupils in turn read a column of words following the key word; 40 (5) pupils are invited to pick out the words with the graphemes oo, ow, ea. At the very beginning, a pupil is compelled to look at each printed letter separately in order to be sure of its shape. She/He often sees words and not sense units. For instance, she/he reads: The book is on the desk and not (The book is) (on the desk). Of particular interest here is the question `how do fluent readers recognize words? ' It is now known that fluent readers do not process words as `wholes'. In normal reading, they process individual letters during each fixation. They make use of knowledge of spelling patterns, word patterns and the constraints of syntax and semantics to produce a phonetic version of the text (though this is usually produced after, rather than before, words have been recognized). Some scholars also suggest six word recognition strategies: Context clues. Figuring out what the word is by looking at what makes sense in the sentence. PSR/morphemic analysis. Figuring out what the word is by looking at the prefix, suffix, or root word. Word analysis/word families. Figuring out what the word is by looking at word families or parts of the word you recognize. Ask a friend. Turn to a friend and say, “What's this word? ” Skip the word. If you are still creating meaning, why stop the process to figure out a word? Phonics. Using minimal letter cues in combination with context clues to figure out what the word is. It is an easy and natural that the direct method facilitates oral work. The disadvantage of this method is that it encourages the learner the habit of reading one word at a time. All words cannot be taught by using pictures. There are abstract words, full meaning of which cannot be understood through single, separate words. Moreover, it ignores spelling. 41 2.4. The Phrase Method The phrase method lies midway between the word method and the sentence method. It helps in extending the eye span. Phrases can be presented with more interesting material aids. The teacher prepares a list of phrases and writes one phrase on the blackboard. He asks the pupils to look at the phrase attentively. The teacher reads the phrase and pupils repeat it several times. New phrases are compared with the phrases already taught. It has all the limitations of the word method. It places emphasis on meaning rather than reading. 2.5. The Sentence Method The most difficult thing in learning to read is to get information from a sentence or a paragraph on the basis of the knowledge of structural signals and not only the meaning of words. Pupils often ignore grammar and try to understand what they read relying on their knowledge of autonomous words. And, of course, they often fail, e. g., the sentence "He was asked to help the old woman" is understood as "Его попросили помочь старой женщине", in which the word ‘he’ becomes the subject and is not the object of the action [20; 181]. In this method the whole sentence is the minimum meaningful unit. It is also a “look and say method”. This method is used in situational teaching. Pupils learn words and letters of the alphabet afterwards. Flash cards are used. The flash card contains the whole sentence. The method is useful for continuous reading. Words and sentences should be familiar to the children. The sentence method can be used effectively only when the children are already able to speak the language. The procedure of this method is sentence -phrase-words-letters. The sentence method deals with the sentences as units of approach in teaching reading. The teacher can develop pupils' ability to read sentences with correct intonation. Later the sentence is split up into words. It facilitates speaking and is natural as well as psychological. It develops the eye span and helps in self learning. It makes use of visual aids. However, readers find it difficult to read a sentence without the knowledge of words and letters. Thus, it is rather a time consuming method [25]. 42 2.6. The Story Method. The Peculiarities of Reading Comprehension The story method is an advanced method over the sentence method. It creates interest among the children. It gives the complete unit of thought. The teacher tells the story in four or five sentences illustrated through pictures. The children first memorize the story and then read it. The limitations of this method consist in failing to develop the habit of reading accurately and putting a heavy load on the memory of the pupil. Special attention is given to intonation since it is of great importance to the actual division of sentences, to stressing the logical predicate in them. Marking the text occasionally may be helpful [20; 184]. Teachers should not forget to perform before-reading-practices: Teach the pronunciation of difficult to read words; If pupils can read the words in a passage accurately and fluently, their reading comprehension will be enhanced. Word recognition and decoding skills are necessary, though not sufficient for reading comprehension. According to the National Reading Panel, systematic and explicit decoding instruction improves pupils' word recognition, spelling, and reading comprehension. Fluent reading in the primary grades is related to reading comprehension [5; 6]. Selection of words for decoding instruction: 1. Use the list of difficult to read words provided in your program. 2. If a list of words is not provided or inadequate for your pupils, preview the passage selecting the difficult to read words. 3. Divide the difficult to pronounce words into two categories for instructional purposes: a) Tell Words (irregular words, words containing untaught elements, and foreign words); b) Strategy Words (words that can be decoded when minimal assistance is provided); Teach the meaning of critical, unknown vocabulary words. 43 Vocabulary is related to reading comprehension. If pupils understand the meaning of critical vocabulary in the passage, their comprehension will be enhanced [5; 14]. Gap in word knowledge persists though the elementary years. Moreover, the vocabulary gap between struggling readers and proficient readers grows each year. Methodists, as Zimmermann and Hutchins identify 7 reading comprehension strategies: 1. activating or building background knowledge; 2. using sensory images; 3. questioning; 4. making predictions and inferences; 5. determining main ideas; 6. using fix-up options; 7. synthesizing [17; 11]. Reading in chorus, reading in groups in imitation of the teacher which is practiced in schools’ forms; The result is that pupils can sound the text but they cannot read. The teacher should observe the rule "Never read words, phrases, sentences by yourself. Give your pupils a chance to read them." For instance, in presenting the words and among them those which are read according to the rule the teacher should make once pupils read these words first. This rule is often violated in school. It is the teacher who first reads a word, a column of words, a sentence, a text and pupils just repeat after the teacher [20; 182]. 2.7. Approaches to Correcting Mistakes In teaching reading the teacher must do the best to prevent mistakes. Teachers may however, be certain that in spite of much work done by them, pupils will make mistakes in reading. The question is who corrects their mistakes, how they should be corrected, when they must be corrected. The opinion is that the pupil who has made a mistake must try to correct it himself/herself. If she or he cannot do it, his/her classmates correct his/her 44 mistakes. If they cannot do as the teacher corrects the mistake the following techniques may be suggested: 1. The teacher writes a word (e. g., black) on the black board. She or he underlines “ck” in it and asks the pupil to say what sound these two letters convey. If the pupil cannot answer the question, the teacher asks some of his or her classmates. They help the pupil to correct his/her mistake and she/he reads the word. 2. One of the pupils asks: «What is the English for “чёрный”»? If the pupil repeats the mistake, the "corrector" pronounces the word properly and explains the rule the pupil has forgotten. The pupil now reads the word correctly. 3. The teacher or one of the pupils says: Find the word «чёрный» and read it. The pupil finds the word and reads it either without any mistake if his/her first mistake was due to his/her carelessness, or she/he repeats the mistake. The teacher then tells him/her to recollect the rule and read the word correctly. 4. The teacher corrects the mistake himself/herself. The pupil reads the word correctly. The teacher asks the pupil to explain to the class how to read “ck”. The teacher tells the pupil to write the word black and underline “ck”. Then she/he says how the word is read. There are some other ways of correcting pupils' mistakes. The teacher should use them reasonably and choose the one most suitable for the case. Another question arises: whether teachers should correct a mistake in the process of reading a passage or after finishing it. Both ways are possible. The mistake should be corrected at once while the pupil reads the text if she/he has made it in a word which will occur two or more times in the text. If the word does not appear again, it is better to let the pupil read the paragraph to the end. Then the mistake is corrected. A teacher should always be on the alert for the pupils' mistakes, allow their reading and mark their mistakes in pencil [20;186]. 45 CONCLUSION In the present qualification paper there has been made an attempt to analyze peculiarities of teaching reading methods in the light of foreign language acquisition and English teaching methodology. On the basis of the material collected the following conclusions may be inferred: Reading is one of the key language skills that pupils should acquire in the process of learning a foreign language. Moreover, it is not only the goal of education but also a means of learning a foreign language as while reading pupils review sounds and letters, vocabulary and grammar, memorize the spelling of words, the meaning of words and word combinations i.e. they polish their foreign language knowledge. Reading skills are the cognitive processes that a reader uses in making sense of a text. To become a proficient reader language learners should master an automatic letter and word recognition and the ability to use context as an aid to comprehension. To make teaching reading effective it is advisable to focus on one skill at a time, explain the purpose of given tasks, establish connection with the previously acquired knowledge and skills, make usage of visual and audio aids, discuss problematic issues etc. Teachers should also keep in mind that reading is not a passive skill, make pupils engaged with what they are reading, encouraged them to respond to the content of a reading text not just to the language, to make sure that tasks correspond to the topic and level of the pupils etc. All in all, there are six important methods of teaching reading and they are as follows: 1. the alphabetic method / ABC method / or spelling method; 2. the phonic method; 3. the word method; 4. the phrase method; 46 5. the sentence method; 6. the story method. 1. The pros of alphabetic method are that it gives the pupils sufficient opportunity to see words and helps them to build up the essential visual image. However, as it is dull and monotonous process it appears to be a difficult and lengthy method that does not expand the eye-span. 2. The phonic method is based on teaching the sounds that match letters and groups of letters of the English alphabet. I t is linked with speech training and helps to avoid spelling defects. Nevertheless, the drawback of the method lies in the facts that meaning is not given priority in this method, additionally, it may delay the development of reading words as a whole. 3. The word method, otherwise known as “Look and say" method teaches to read words as whole units, rather than breaking the word down into individual letters or groups of letters. It is an easy and natural direct method that facilitates oral work but at the same time it encourages the learner. 4. The phrase method lies midway between the word method and the sentence method. It helps in extending the eye span. This method has the same limitations as the word method has. It places emphasis on meaning rather than reading. 5. The sentence method or “look and say method” in other words is often used in situational teaching. It perceives the whole sentence as the minimum meaningful unit. The procedure goes as follows: sentence – phrase – words letters. Readers find it difficult to read a sentence without the knowledge of words and letters. Thus, it is rather a time consuming method. 6. The story method is the most advanced one. The teacher tells the story in four or five sentences illustrated through pictures. The children first memorize the story and then read it. Before-teaching-practices should not be neglected with this method. Scholars recognize six word recognition strategies, namely, context clues, morphemic analysis, word analysis, ask a friend, skip the word, phonics. 47 Activating or building background knowledge, using sensory images, questioning, making predictions and inferences, determining main ideas, using fix-up options, synthesizing are the seven reading comprehension strategies. The procedure of introducing new vocabulary to pupils may take the following route: Step 1: word introduction; Step 2: pupil-friendly explanation; Step 3: illustrative examples; Step 4: checking understanding. Teachers should be very reasonable and careful with error correction and choose the most suitable for the case as it may psychologically influence learners. The correction may be made by the teacher or another pupil during or after reading. All the things considered, reading is a language activity and ought not to be divorced from other language activities. To read effectively in English secondlanguage pupils need to learn to think in English. The methods of any teaching reading a lesson should be chosen according to the learner's level of skill development. Teaching reading is a job for an expert who has to create conditions whereby learners can learn and develop their reading skills. Reading is a skill that will empower everyone who learns it. They will be able to benefit from the store of knowledge in printed materials and, ultimately, to contribute to that knowledge. Good teaching enables pupils to learn to read and read to learn. The role of the teacher in the teaching-reading process should be of a companion rather than the boss. Teaching can be made interesting and innovative if the efforts are put in to make learning an enjoyable experience. Successful teaching is where effective learning takes place with the use of appropriate knowledge, the right emotion and accurate application of scientific devices. With consistent progress in science and technology and other areas of study, it is the duty of the teacher to adopt the best methods and employ the best devices to ensure rapid growth in the teaching process. Teachers must be aware of the 48 progress that pupils are making and adjust instruction to the changing abilities of pupils. Both research and classroom practices support the use of a balanced approach in instruction. Because reading depends on efficient word recognition and comprehension, instruction should develop reading skills and strategies, as well as build on learners' knowledge through the use of authentic texts. Similarly, the most effective way of dealing with the problem of cultural meaning in texts is to encourage pupils to read by themselves, choosing subjects related initially to their own interests so that they bring motivation and experience to reading. As their understanding of other cultures and of unfamiliar views increases through reading, they will bring to their reading activities a gradually increasing capacity to understand the full meaning of texts. When reading comprehension breaks down, different pupils need to find ways to repair their understanding. This is where the importance of knowing how to teach reading strategies come in, so as to facilitate the reading process and give pupils a clear sense of what they are reading. Pupils can become easily frustrated when they do not understand what they are reading and as a result, they become demotivated. A teacher needs to design and teach different strategies in order to help pupils close the gaps in their understanding. The ultimate challenge for the teacher is to know exactly which strategy is useful and most beneficial to teach, since each pupil needs different strategies. This qualification paper in this respect, gives many strategies and a few general pointers for how to teach them. The research is only a modest contribution to the issue of teaching reading methodology and thus further investigation into the sphere is highly recommended. 49 REFERENCES 1. Каримов И.А. Постановление от 10 декабря 2012 года «О мерах по дальнейшему совершенствованию системы изучения иностранных языков». 2. Alyousef H.S. Teaching Reading Comprehension to ESL/EFL Learners The Reading Matrix, №2, 2005. p.143-154. 3. Anderson, N. Exploring second language reading: Issues and strategies. Boston: Heinle & Heinle, 1999. 4. Archer A.L. Before Reading Practices. Curriculum Associates, Skills for School Success. 2006, p. 56. 5. Beatrice S. Teaching Reading in a Second Language. London: Pearson Education, 2008. 6. Brindley S. Teaching English. London, NY: 1994. p. 268. 7. Calhoun E.F. Teaching Beginning Reading and Writing with the picture word inductive model. Alexandria, Virginia: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1999. p. 125. 8. Day Richard & Bamford J. Extensive Reading in the Second Language Classroom. Cambridge University Press, 1998. 9. Day Richard & Bamford J. Extensive Reading Activities for Teaching Language. Cambridge University Press, 2004. 10.Harmer J. How to Teach English. London: Longman, 2001. p.199. 11.Harmer J. The practice of English Language Teaching. NY: Longman, 2001. p. 386. 12.Harrison C. Methods of Teaching Reading: Key Issues in Research and Implications for Practice / Interchange, №39 - 1996. p. 1-16. 13.Head, K. and Taylor, P. Readings in Teacher Development. Heinemann, 1997. 14.Johnson A.P. Teaching Reading and Writing. Toronto, Plymouth: Rowman and Little field Education, 2008. p. 260. 50 15.Lems K. Teaching Reading to English Language Learners. NY, London: The Guilford Press, 2010. p. 256 16.Moreillon J. Collaborative Strategies for Teaching Reading Comprehension . Chicago: American Library Association, 2007. p.172. 17.Nutley S. Teaching children to read. London: House of Commons Education and Skills Committee, 2005. p. 47 18.Nuttall, Christine. Teaching Reading Skills in a Foreign Language. Oxford: Heinemann, 1996. 19.Rogova G.V. Methods of Teaching English. Leningrad, Prosveshenie, 1975. p.312. 20.Sweeney S. The importance of reading in foreign language teaching// Authentically English, №2 - 1993. 21.Sylva K. Teaching Reading is Rocket Science / American Federation of Teachers. New Jersey: AFT, 2004. p. 38 22.Willis J. Teaching English through English. London: Longman, 1981. p. 192 23.Willy van Elsacker. Development of reading comprehension: The engagement perspective. Feboprint, Enschede, 2002. 24.http://www.eslkidstuff.com 25.http://nsambatcoumar 26.http://itac.glp.net 27.http://www.childrens-books-and-reading.com/look-and-say.html 28.http://www.btinternet.com 29.http://www.readingmethod.com 30.http://www.pdf-finder.com • 51 APPENDIX READING ACTIVITIES A-E Activity A Read a short story of your choice. Write a journal entry summarizing the main points of the plot. Activity B Read the story and decide how it should end. What happens next? Write a conclusion. Activity C Read the first part of the story. What do you think these words mean? clever, create, living, dead, experiment, successful Activity D Dialogue Man: I’ve lost my dog. Lottie: What does it look like? Man: What do you mean – ‘it’? My dog is a ‘she’. Lottie: Oh, sorry. What does she look like? Man: Well, she’s got four legs.. Lottie: Really? Man: Yes. She’s quite big, and she’s white with brown eyes. Lottie: How big is she? Man: Well, quite big, not very big. She’s about this big. And she looks a bit like me. Lottie: Like you? Read the dialogue again. Which sentences mean the same as these? 1. Please describe it. 2. Please describe her. 3. My dog is female. 4. Please describe the dog’s size. 5. Look! This is her size. 52 6. The dog’s face and my face are not very different. Activity E Read the story and fill in the blanks. There is one missing word for each blank. I used to live in Turkey. While I was ___, I studied Turkish folk ___ and music. There is a great tradition of dance and ___ in this country – in fact, there are thousands of ____ dances one can learn. The ___ learn many of the basic ones in school and at wedding and other ____ . There are different dances for each region of the country, and each ___ has its own costumes, too. 53