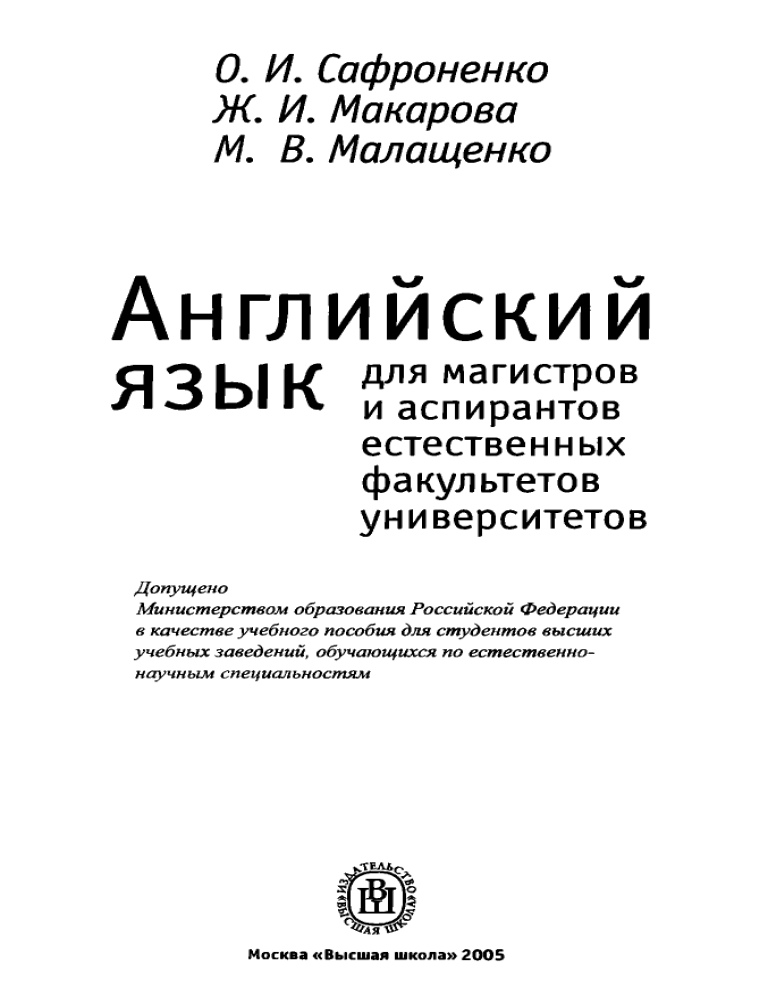

0. И. Сафроненко

Ж. И. Макарова

М. В. Малащенко

Английский

g O L jl/

/ lO D IrV

для магистров

и аспирантов

естественных

факультетов

университетов

Допущено

Министерством образования Российской Федерации

в качестве учебного пособия для студентов высших

учебных заведений, обучающихся по естественно­

научным специальностям

Москва «Высшая школа» 2005

уцк 811.111

ББК 81.2Англ

С21

Рецензент:

Кафедра английского и французского языков

Южно-Российского государственного технического университета

(зав. кафедрой проф. АС. Кутъкова)

Редактор английского текста

магистр гуманитарных наук Марк Стронг (США)

С21

Сафроненко, О.И.

Английский язык для магистров и аспирантов естественных

факультетов университетов: Учеб. пособие / О.И. Сафроненко,

ЖИ. Макарова, М.В. Малащенко. —М.: Высшая школа, 2005. —

175 с.

ISBN 5-06-004973-6

Цель пособия — обучение магистров и аспирантов естественных

факультетов классических и технических университетов устной и пись­

менной речи на английском языке.

Пособие включает научно-популярные статьи из зарубежных пе­

риодических изданий, а также задания и упражнения, стимулирующие

творческую речевую деятельность на английском языке. Пособие со­

держит справочный материал, изучение которого обучает магистров и

аспирантов написанию и оформлению научных статей, а также веде­

нию научной корреспонденции на английском языке.

«Приложение» включает наиболее употребительные сокращения,

термины и словосочетания, принятые в англо-американской научнотехнической литературе, и другую полезную информацию.

Для магистров и аспирантов естественных факультетов университе­

тов.

© ФГУП «Издательство «Высшая школа», 2005

ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ

Данное учебное пособие, состоящее из шести разделов и при­

ложения, имеет своей целью обучение магистров и аспирантов ес­

тественных факультетов классических и технических университе­

тов устной и письменной научной речи на английском языке, в том

числе развитие и совершенствование навыков всех видов речевой

деятельности — говорения, аудирования, чтения и письма. Посо­

бие составлено в соответствии с требованиями действующей про­

граммы по английскому языку для неязыковых специальностей

высших учебных заведений.

В основу пособия положены принципы коммуникативной направ­

ленности и взаимосвязанного обучения видам речевой деятельности

на иностранном языке. Данный подход определяет и структуру посо­

бия, которая в определенной мере отражает последовательность эта­

пов работы исследователя над научной проблемой:

Section 1. Reading and Speaking —изучение имеющейся литера­

туры и ее обсуждение с коллегами и научным руководителем;

Section 2. Reading and Summarizing Information —извлечение ин­

формации и ее обобщение в виде реферативного обзора;

Section 3. Speaking —определение темы исследования, гипоте­

зы, методов проведения эксперимента и представление получен­

ных результатов на научной конференции;

Section 4. Writing Research Papers —оформление полученных ре­

зультатов в виде научной статьи;

Section 5. Writing Letters —ведение переписки с издательствами

и оргкомитетом конференции по поводу публикации статьи или

принятия участия в научной конференции.

Цель раздела Section 6. Listening —активизация и развитие на­

выков понимания научной речи на английском языке.

Преподавателям, работающим по данному пособию, предостав­

ляется свобода выбора и компоновки материалов различных раз­

делов, исходя из конкретных задач курса, реальных потребностей

обучаемых, а также их уровня владения английским языком.

Такой подход к организации учебного материала позволяет реа­

лизовать принцип индивидуализации в обучении и активизации

самостоятельной работы магистров и аспирантов.

Учебное пособие рассчитано в среднем на 60 часов аудиторной

работы, однако при иной сетке часов разделы 4 и 5 могут быть пред­

ложены для самостоятельного изучения.

4

П редисловие

Лексический диапазон учебною пособия, охватывающий ши­

рокие пласты научной и профессиональной лексики, позволяет

магистрам и аспирантам значительно расширить свой словарный

запас. Предлагаемые задания и упражнения, имеющие коммуни­

кативную направленность, в сочетании с интересным содержани­

ем текстового материала, стимулируют творческую речевую дея­

тельность на английском языке.

Первый раздел “Reading and Speaking” включает научно-попу­

лярные статьи из газеты “SIAM (Society for Industrial and Applied

Mathematics) News”, журнала “The Discoveiy Journal” (США) и дру­

гих зарубежных периодических изданий. Работа над каждым тек­

стом начинается с предгекстовош упражнения, позволяющею вы­

явить мнение и стимулировать высказывания обучаемых по

обсуждаемым в статьях проблемам. Эта часть пособия нацелена на

комплексное развитие навыков беспереводного чтения с последую­

щим выходом в устную речь, предусматривающим обсуждение ин­

формации, извлеченной при чтении. При развитии навыков уст­

ной научной речи особое внимание уделяется совершенствованию

навыков ведения дискуссии, заложенных в рамках базового курса

изучения английского языка: умении высказывать свое мнение, ар­

гументированно его отстаивать, выражать согласие или несогласие

с другими точками зрения и т.д. Эти навыки также закрепляются в

третьем разделе “Speaking”. В данной части, наряду с текстами на­

учного содержания, в разделе “For Fun” приводятся микродиалоги,

высказывания известных людей и шутки об ученых.

Второй раздел “Reading and Summarizing Information” , включаю­

щий семь статей из американских периодических изданий (см. Спи­

сок использованной литературы), предусматривает развитие навы­

ков чтения научной и научно-популярной литературы с целью

извлечения основной информации по определенному алгоритму и

последующее ее обобщение в устной реферативной форме. В разде­

ле приводятся наиболее употребительные клише, используемые для

обобщения информации.

Третий раздел “Speaking”, состоящий из восьми частей, имеет

целью развитие и активное закрепление навыков устной речи по

темам, связанным с научно-исследовательской работой магистров

и аспирантов: Field of Science and Research, Research Problem, His­

torical Background of Research Problem, Current Research (Purpose and

Methods), Current Research (Results and Conclusions), Conference Par­

П редисловие

5

ticipation (How to Chair a Conference; Presenting a Paper). Каждая

часть включает активную лексику по обсуждаемой тематике, ото­

бранную с учетом частотности ее употребления. Лексика раздела

закрепляется в упражнениях, способствующих развитию и совер­

шенствованию навыков как диалогической, так и монологической

речи. Интерес представляют заключительные упражнения каждой

части, в которых учащимся предлагается разыграть одну из ситуа­

ций возможного профессионального или научного общения.

Цель четвертого раздела “Writing Research Papers” —развитие на­

выков письменной научной коммуникации. В него входят справоч­

ные материалы, требования к написанию и оформлению научных

статей на английском языке в соответствии с международными стан­

дартами, образцы научных статей. Последовательное выполнение

заданий раздела предполагает написание магистрами и аспиранта­

ми статей по проблемам проводимых ими исследований. Данный

раздел может быть предложен для самостоятельного изучения.

Пятый раздел учебного пособия ‘Writing Letters”, состоящий из

пяти частей, включает справочный материал, рекомендации, много­

численные образцы написания и ведения научной корреспонденции:

писем-запросов, писем-ответов, писем-приглашений, писем-просьб,

а также писем, выражающих благодарность за предоставление инфор­

мации и материалов, и тд. Данный раздел также может быть предло­

жен для самостоятельного изучения.

В шестой раздел “Listening” входят тексты общенаучной и про­

фессиональной тематики в аудиозаписи или предъявляемые со слу­

ха. Предлагаемые в разделе упражнения направлены на развитие на­

выков извлечения на слух ключевой информации, ее последующего

обсуждения в устной форме или обобщения в письменном виде. Со­

держание аудиозаписей по теме “How to Write a Technical Report” до­

полняет информацию четвертого раздела пособия “Writing Research

Papers”.

В пособие также входит обширный раздел «Приложения», кото­

рый включает наиболее употребительные сокращения, термины и

словосочетания, принятые в англо-американской научно-техниче­

ской литературе, список интернациональной лексики, представляю­

щей трудности в произношении, и другую информацию (всего 21

приложение).

CONTENTS

Section 1. Reading and Speaking..........................................8

Text 1. The Theory of Knowledge................................................... 8

Text 2. What Can Computers D o?............................................ 10

Text 3. Science and Society in the U SA .................................... 13

Text 4.................................................................................................15

Text 5. Bill Gates’s Vision.......................................................... 17

Text 6. Did Poincare Point the Way to Twentieth-Century Art? .... 19

Text 7. Challenge to Our Darwinian Durability.........................21

Section 2. Reading and Summarizing Information

Text 1.

Text 2.

Text 3.

Text 4.

Text 5.

Text 6.

Text 7.

24

Karle and Haus Receive National Medal of Science...24

Japan Stores Sunlight in Crystals...................................26

Viral Soup...................................................................... 28

Energy-Converting Plastic F ilm ....................................30

Why Care About Global Wanning?................................31

Virtual Electron Microscope LaboratoryDemonstrated ... 34

Simulations Predict Failure Mechanismsof Lubricants in

Nanometer-Scale Devices.............................................. 35

Section 3. Speaking.........................

38

1. Field of Science and Research.....................................................38

2. Research Problem ........................................................................39

3. Historical Background of Research Problem...............................41

4. Current Research. Purpose and M ethods....................................43

5. Current Research. Results and Conclusion.................................44

6. Conference................................................................................... 46

7. How to Chair a Conference.........................................................48

8. Presenting a Paper....................................................................... 49

Section 4. WHting Research P apers.................................. 55

1. Gathering Data and Writing Summary N otes............................. 55

2. Organizing Ideas...........................................................................56

3. Writing a Paper: Structure, Linguistics and Style........................ 56

Section 5. WHting L etters...................................................74

1. Letter Layout................................................................................74

2. Letters of Invitation..................................................................... 84

3. Letters of Request........................................................................ 92

4. Letters of Inquiry........................................................................101

5. Letters of Thanks........................................................................ 107

Section 6. Listening............................................................I l l

Listening 1. Generations of Space Robots..................................... I ll

Listening 2. The “Ranger” Space R obot....................................... I ll

Listening 3. Robots in Space......................................................... 112

listening 4. How to Write a Technical Report...............................112

4.1. The Title.............................................................112

4.2. Abstract Writing.................................................. 113

4.3. The Structure of a Technical Report.................... 113

4.4. Acknowledgements............................................. 114

4.5. References.......................................................... 115

4.6. The Style of a Scientific Report............................ 115

4.7. Bibliography and Appendices............................... 115

Tapescripts..................................................................................... 117

Appendices.................................................................................... 128

List of Materials U sed....................................................................175

Section 1

READING AND SPEAKING

TEXT 1

Before you read

1. “What goal can be reached by the science to which I am dedicating myself?” is the

question that interested Albert Einstein. What answer would you give to this

question?

2. Now read the text and find other questions Albert Einstein asked in his letter.

Hie Theory of Knowledge

(From Albert Einstein’s letter of 1916)

“How does a normally talented research scientist come to concern

himself with the theory of knowledge? Is there not more valuable work

to be done in his field? I hear this from many of my professional col­

leagues; or rather, I sense in the case of many more of them that this is

what they feel.”

“I cannot share this opinion. When I think of the ablest students

whom I have encountered in teaching —i.e., those who distinguished

themselves by their independence ofjudgment, and not only mere agil­

ity —I find that they had a lively concern for the theory of knowledge.

They liked to start discussions concerning the aims and methods of

the sciences, and showed unequivocally by the obstinacy with which

they defended their views that this subject seemed important to them.”

“This is really not astonishing. For when I turn to science not for

some superficial reason such as money-making or ambition, and also

not (or at least not exclusively) for the pleasure of the sport, the de­

lights of brain-athletics, then the following questions must bumingly

interest me as a disciple of this science: What goal will and can be

reached by the science to which I am dedicating myself? To what ex­

tent are its general results “true”? What is essential, and what is based

only on the accidents of development? ...”

9

R eading and Speaking

“Concepts which have proved useful for ordering things easily as­

sume so great an authority over us, that we forget their terrestrial origin

and accept them as unalterable facts. They then become labelled as

“conceptual necessities,” “a priori situations,” etc. The road of scien­

tific progress is frequently blocked for long periods by such errors. It is

therefore not just an idle game to exercise our ability to analyze famil­

iar concepts, and to demonstrate the conditions on which their justifi­

cation and usefulness depend, and the way in which these developed,

little by little...”

Discussion

How would you answer the questions?

1. Do you think the questions suggested in paragraph 1 were posed by

Albert Einstein? Give your reasons to confirm your answer / opinion.

2. What opinion is expressed in paragraph 1? Why couldn’t Albert

Einstein share that opinion?

3. Why do you think the questions posed by Albert Einstein in para­

graph 3 bumingly interested him?

4. Comment on the idea expressed in the sentence “The road of sci­

entific progress is frequently blocked for long periods by such er­

rors.”

5. “Scientific progress is impossible without being concerned with

the theory of knowledge.” Agree or disagree.

For Fun

Read the dialogue and then act it out:

A Close Translation

Smith: My cousin translates scientific papers from German into En­

glish. Now, for instance, he is translating an article by Ein­

stein.

Black: Has he really been translating so great a scientist?

Smith: Yes, he has. And, in fact, I consider it an exceptionally good

translation.

10

Section 1

Black:

Smith:

Black:

Smith:

Do you? Is there anything particularly good about it?

Certainly there is. It is a perfectly close translation.

A close translation? How can you make that judgment?

Because in all the places where I don’t understand Einstein in

the original, I do not understand him in my cousin’s transla­

tion either.

TEXT 2

Before you read

1. Charles McCabe once said: “Any clod can have the facts, but having opinions is an

art.” Discuss the pros and cons of this statement.

2. Now read the following text and see whether the author of the following text is of

the same opinion. What other problems are discussed in this article?

What Can Computers Do?

Neville Holmes, University of Tasmania

Marty Leisner answers his own question “Do Computers Make Us

Fools?” with the statement: “It seems that computers make people

incapable of independent thought.” On the other hand, he concludes

that “reliance on them ... might make us fools,” and this, together

with many of his other comments, answers quite a different question

and answers it well. But it seems to me that neither question is the

basic question.

So what is the real question? What is the basic problem? The con­

text is that computers are seen as underpinning social change. The

mistake is that computers are seen as causing social change. Let me

illustrate one relevant social change.

Computer as Scapegoat

In 1970 I returned to Australia after living for a while in the Hud­

son River Valley in America, where there was a fairly widespread use of

computers and punched cards. The state of New York had a veiy sim­

ple and effective drivers’ license system based on stub cards, which

required only that you send back the stub with your payment each year;

the remainder of the card was your license.

11

R eading and Speaking

When I went to get a license in Canberra, I was given a three-part

form. The form not only asked for many more personal details than

New York ever required, it required them to be written three times.

When I mildly criticized the form design at the counter, I was solemn­

ly informed that the design was as it was because of The Computer. I

left it at that, but my later inquiries revealed that the department had

neither a computer nor any plans to get one.

This incident altered me to the most important social role of the com­

puter, then as now; universal scapegoat. I have seen nothing since to change

my mind on this, and indeed I have seen much to confirm it. The social

change here is that people seem to be eager to use computers to avoid

personal responsibility. Computers are being used to replace personal val­

ues with impersonal ones, like the ultimate abstraction —money.

Computer as Tool

Computers are merely tools. They are not members of society; they

are not even pseudomembers, like corporations and governments. They

are independent agents. Like cars and telephones, they only do things

if and when someone uses them. They can neither be blamed for what

they do (are used for), nor can they be given credit for what they do

(are used for). If there is blame or credit then it belongs to the users, or

to the owners, or to the designers, or to the manufacturers, or to the

researchers, or to the financiers, never to the computer itself.

Computers cannot make us fools —they can only allow us to be

foolish faster. And they can be used by others to make fools of us, for

profit or power.

This is not understood by everyone because the computer industry

and the computing profession seem to be saying otherwise. We seem to

be saying that computers are like people; that they have memory, intel­

ligence, understanding, and knowledge; that they are even friendly.

How ignorant! How impressive! How profitable!

Attitudes to Computers

Those in the industry who warned against anthropomorphic lan­

guage have been ignored. The people who put together the first stan­

dard vocabularies for the industry urged people to call the devices where

data are put “stores” or “storage,” not “memories.” To suggest there is

12

Section 1

any likeness between the computer storage and the memories a human

might reconstruct is farcical, if not insulting.

Those in the industry who urged that people be distinguished from

machines have been ignored. The people who put together the first

standard vocabulary for the industry installed such a distinction in its

very first two definitions. In brief, they defined “data” as representa­

tions of facts or ideas, and they defined “information” as the meaning

that people give to data. Only people can process information; ma­

chines can process only data. Embodying this fundamental distinction

in the definition of the two most basic computing terms was a com­

plete waste of ink.

As long as we allow people to think of computers as anything else

than machines to be owned and used, powerful people and institutions

will be able to use computers as scapegoats and avoid blame for the

social inequities they are able to bring about for their own benefit by

using computers.

Discussion

How would you answer the questions?

1. What is the author’s reason for choosing such a preface to his article?

2. Why does Neville Holmes refer readers with concerns about com­

puters and social inequities?

3. What, in your opinion, is the social role of computers?

4. Why does the author stick to the idea that “computers cannot make

us fools?”

5. Neville Holmes distinguishes between such terms as “storage” and

“memory,” “data” and “information.” Why?

For Fun

Comment on the following:

The reasonable man adapts himself to the world, the unreasonable

man persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all

progress depends on the unreasonable man.

G.B. Shaw

13

R eading and Speaking

TEXT 3

Before you read

1. Comment on the statement: “Science is a powerful engine by which the genius of

the few is magnified by the talents of the many for the benefits of all.”

2. Now read the text and determine its main points.

Science and Society in the USA

Science on the scale that it exists and is needed today can, howev­

er, be maintained only with large amounts of public support. Largescale public support will be provided only if science and technology

are meeting the critical needs of society. Intellectual progress, as meas­

ured by advances in specific scientific disciplines, is not in itself suffi­

cient to generate such support. Perhaps it should be, but it is not. Pub­

lic support for science may be wise policy, but it is not an entitlement.

The central problem is that the costs of meeting the needs of soci­

ety are too high, and the time scale for meeting them is too long. Both

the ideals and the pragmatics of American society are based on im­

provement in the quality of life. We expect better health care, better

education, economic security. We expect progress towards the reduc­

tion, if not outright elimination of poverty, disease, and environmental

degradation.

Progress towards these goals has recently been frustratingly slow

and increasingly expensive. The heavy costs of providing and improv­

ing health care and education are examples.

The situation has produced a volatility in public opinion and mood

that reflects a lack of confidence in the ability of government and other

sectors of society, including science and technology, to adequately ad­

dress fundamental social needs.

If this mood hardens into a lack of vision, of optimism, of belief in

the future, a tremendous problem for science will result. Science, in

its commitment to innovation and expanding frontiers of knowledge,

is a thing of the future.

The vistas of science are inspiring. Condensed matter physics is

embarked on materials by design, nanotechnology and high tempera­

ture superconductivity, each containing the seeds of new industries as

14

Section 1

well as new scientific understanding. Molecular biology is in full bloom

with a vast potential for fiirther intellectual progress, betterment of hu­

man (and plant and animal) health, and commercialization. Neuro­

science seems poised for dramatic progress.

Research into the fundamental laws of physics is aiming at a pin­

nacle. There is a candidate theory —the superstring theory —which is

proposed as a unification of all the known fundamental forces in na­

ture and which is supposed to give an account, complete in principle,

of all physical phenomena, down to the shortest distances currently

imaginable. At the largest scales of distance, observational astronomy

is uncovering meta-structures which enlarge the architecture of the

universe —a deepening of the problem of cosmology preliminary to its

resolution.

Underpinning much of this progress, and progress in countless other

areas as well, has been the emergence of scientific computing as an

enabling technology.

All this is first-rate science. All this is not enough —either to fore­

stall change or to ensure adequate support for science in the present

climate. Why it is not enough — and what else is required — are the

subjects of a special inquiry.

Discussion

How would you answer the questions?

1. Are there statements in the text that you disagree with? What are they?

2. Are you aware of the latest achievements in your field of science?

What are they?

3. Why do you think the achievements of science are not sufficient to

ensure adequate support for science?

4. Ifyou were in power what would you do to support science in Russia?

For Fun

Comment on the following:

Discussion is a method of confirming others in their errors.

A. Bierce

15

R eading and Speaking

TEXT 4

Before you read

1. Comment on the statement: “We get the best from people by expecting the

best.”

2. Read some reminiscences of Thomas E. Hull’s students and then give the text

a title.

***

He was an effective leader who got commitment by soliciting ad­

vice, who got the best from people by expecting the best, whose fun­

damental decency was apparent in every interaction. He taught by

example that the highest standards can be reached cooperatively, with­

out envy, jealousy or corrosive competition.

Even before I met Tom, he had a significant influence on me: I

used one of his books in the first computer science course that I took

at the University of Toronto in the early 1970s. Tom was the author

of seven textbooks that played a very important role in establishing

computer science as in academic discipline in the late 1960s and ear­

ly 1970s.

I was fortunate to have Tom as an instructor for the first course

on numerical analysis that I took at the university. It was clear to all

of us in the class that Tom knew his subject thoroughly. Moreover, his

lectures were very well organized, clear, concise and delivered with a

sense of humour. Many students find numerical analysis a little dry

and somewhat difficult. Tom was well aware of this and motivated his

students by beginning each of his lectures with a short intuitive dis­

cussion of the topic that he was going to talk about that day and by

briefly outlining its importance, often relating the topic to other sub­

jects that we were studying. Tom’s lecturing style was a model for

many of us who later went on to teaching careers ourselves.

Among the many reasons for Tom’s great success as a teacher was

his love of interacting with people. He clearly enjoyed teaching a sub­

ject that was dear to him and seeing others take pleasure in learning

about it. His enthusiasm was infectious and rubbed off on many of

his students.

16

Section 1

I was also fortunate to have Tom as a graduate supervisor, a role in

which he excelled. In part, this was because he was an excellent researcher

himself. When I was a graduate student, about 20 years ago, Tom was the

chairman of the computer science department, a member of the NSERC

(Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada) com­

mittee on grants and scholarships, an editor of three prestigious jour­

nals, the author of several of the most important papers in our area, and

an invited speaker at many international conferences. He knew most of

the key players in our research area and was aware of the topics on which

they were working. He had a very good sense for what was a good prob­

lem to tackle and what would likely be fruitless.

More importantly, Tom was an excellent graduate supervisor at a

more personal level. His enthusiasm for discussing new ideas with

students was evident. In spite of his extremely busy schedule, he al­

ways found time for his students and he gave all of us the impression

that our work was a high priority for him. He was always supportive,

encouraging, and very generous in his praise of good ideas. But, of

course, not all the ideas that students have are good ones. Tom was

careful not to be too deflating when explaining why some silly scheme

a student had devised was not sound. He usually got the student back

on track and feeling positive about pursuing another line of attack.

Discussion

How would you answer the questions?

1. Give reasons why you have chosen such a title for the text.

2. “The highest standards can be reached cooperatively, without envy,

jealousy or corrosive competition.” Doesn’t this statement con­

tradict the common knowledge that competition helps to achieve

better results in some spheres?

3. “Thomas E. Hull was an excellent supervisor. In part, this was be­

cause he was an excellent researcher himself.” Does it mean that

every excellent researcher can be a good supervisor?

4. “The influence of a teacher on a student is not always a good thing. ”

Give your arguments for or against this statement.

5. What could you say about your thesis supervisor?

17

R eading and Speaking

For Fun

Comment on the following:

I think and think; for months, for years, 99 times the conclusion is

false. The hundredth time I am right.

(A. Einstein)

TEXT 5

Before you read

1. Comment on Henry Ford’s saying: “Had I worked fifty or ten or even five years

before, I would have failed. So it is with every new thing. Progress happens when

all the factors that make for it are ready, and then it is inevitable.”

2. Now read the text and then say if it contains any new information for you about the

Microsoft empire.

Bill Gates’s Vision

It must be remembered that the future of the Microsoft empire

depends heavily on the accuracy of Bill Gates’s vision. If his thoughts

occasionally sound mundane or less than original, it is because they

are the result of a selection process: a person in his position has a le­

gion of experts at his beck and call, plenty of whom generate ideas as

fast as he does. His job is to sort out the ideas worth staking a piece of

the company’s future on. For that, an idea does not have to be origi­

nal, or even all that good, but it does have to fit his vision: a computerfilled world in which Microsoft writes the best-selling software.

Early in 1975, Gates, by then a sophomore at Harvard University,

and Allen, who was working as a programmer in Boston, set out to

overtake the revolution. Their first goal was to write a version of Basic

to run on the Altair. (Altair 8800 was the world’s first truly personal

computer.)

Although they didn’t own an Altair —and indeed had never even

seen one —Allen wrote a program on a Harvard mainframe to simulate

the new computer. So equipped, working virtually nonstop in his dorm

room, often losing track of night and day and routinely falling asleep at

his desk or on the floor, the 19-year-old Grates needed just five weeks to

18

Section 1

complete the task. Later that spring, the pair formed the world’s first

microcomputer software company, eventually naming it Microsoft.

Like Ford before him Gates invented nothing: no computer, no

peripheral, no programming language. He certainly didn’t invent mi­

crochips. What he did was probably inevitable, once the components

became available. He may, however, have been the very first to see how

the 8080 chip (unlike the 8008) could be used to place significant com­

puting power at the disposal of Everyman. He didn’t know what would

be done with it, and he certainly didn’t foresee (as Ford didn’t foresee

LA freeways) that offices, not homes, would house most of the early

PCs. Gates and Allen only knew that, if priced within reason, the prod­

ucts they offered —DOS and Microsoft Basic —would sell.

Gates is eager to distinguish between the services performed by the

present generation of home computers and those to be expected in the

future from a station on an information highway. The current Internet,

he insists, is only a pale imitation of the highway to come. In time,

most of the world’s information will be available to almost anyone in

it. His investigations have convinced him, however, that current satel­

lite technology will never supply the requisite bandwidth (channel ca­

pacity). The transmission of so much information will require that pri­

vate homes be connected to the outside world by underground fiber

optic cables, just as they are now connected by existing sewerage, wa­

ter, electric power, cable TV, and telephone conduits. The required

cable will be installed in due time, he predicts, and will be no more

costly than current networks.

When the powerful computers of the future are connected to the

information highway, you will be able to stay in touch with anyone,

anywhere, who wants to stay in touch with you; to browse through

thousands of libraries, by day or by night; and to retrieve the answers to

varied questions.

You will also be able to watch almost any movie ever made, at any

time of day or night, interrupted only upon request. The instructions

for assembling your latest purchase will be interactive. Shopping chan­

nels will show you only what you ask to see, and the people with whom

you talk by telephone will see a well-groomed likeness of yourself re­

sponding to their jokes and flirtations, even if you are actually dripping

wet from the shower.

19

R eading and Speaking

Discussion

Now test your memory by seeing how many of the following questions you

can answer:

1. What does the future of the Microsoft empire depend on?

2. How is Gates’s job characterized in the article?

3. If you worked at Microsoft would you try to come up with any orig­

inal ideas?

4. What is Gates’s vision?

5. How long did it take Allen and Gates to form the word’s first mi­

crocomputer software company?

6. Gates did not invent anything special. What do you think made

him so famous?

7. What was the only thing that stimulated Gates’s activities?

8. In what way will most of the world’s information be available to

almost anyone in it?

9. What benefits does the information highway provide?

10. What else do you know about the Microsoft empire and its founder?

11. Give your arguments for or against the statement: “Scientists

achieve success when they come down firm the heights of science

to the level of an ordinary man.”

For Fun

Comment on the following:

An eminent mathematician was asked about one of his former pupils.

“Oh, that one,” he said. “He’s become a writer of science fiction.

He lacked the imagination for mathematics.”

TEXT 6

1.

Read the text in order to discuss the creative process.

Did Poincare Point the Way to Twentieth-Century Art?

Henri Poincare is well known to mathematicians for the depth and

breadth of his scientific accomplishments. Nowadays he is even more

20

Section 1

widely known for creating much of the mathematics that has gone into

the revolutionary scientific theory known as chaos. But could the

French mathematician also be responsible for inspiring a similarly dra­

matic revolution in the world of art?

One of Poincare’s essays on science directly inspired the artist

Marcel Duchamp to chart a new course for artistic expression.

Duchamp is famous for what he called “readymades” —such ordi­

nary objects as a hat rack or a snow shovel that became works of art by

virtue of his selecting them. Duchamp’s championing of the artist’s

“special intuition” in interpreting the world paved the way to today’s

unruly art.

But what gave him the idea?

In a section on mathematical creation, Poincare speculates that

unconscious processes continue to sift ideas between periods of active

thought, and that fruitfiil combinations are brought to consciousness

by virtue of their aesthetic appeal. In other words, a creative mathe­

matician is one who recognizes a good idea when it jumps up and bites

him on the brainstem.

According to Poincare, the creative process is set in motion during

a period of concentrated, conscious work. Poincare also describes an

instance in which, unable to sleep because of too much black coffee,

he felt his mind crowded with ideas that collided until they locked into

a stable combination; by the next morning, he had the solution to a

problem that had plagued him for weeks.

Duchamp rs virtually certain to have read Poincare’s essay. The

avant-garde artists of the daywere keenly interested in things scientific

and mathematical, with four-dimensional and non-Euclidean geom­

etries at the top of the list.

Poincare’s vivid description of the effects of coffee also influenced

Duchamp.

Duchamp regarded his 1911 painting Coffee Mill as the “key” to

his work, and at one exhibition he kept coffee beans roasting in a cor­

ner of the room, the aroma being an integral part of the show.

“The fun starts now” as art historians and others begin to decode

Ducfiamp’s work in light of the Poincare connection. The question

is: Which mathematician will inspire the next revolutionary figure in

art?

21

R eading and Speaking

Discussion

How would you answer the questions?

1. What is the definition of the creative process, according to Poincare?

2. “He felt his mind crowded with ideas that collided until they locked

into a stable combination.” Can we conclude that chaos is needed

for the creative process?

3. What must one do to make “ideas jump into one’s brain?” How do

you develop ideas?

4. What do you think might inspire a scientist?

5. What do you think the creative process is?

6. Can a person be taught to be creative?

For Fun

Read the dialogue and then act it out:

Post-graduate: What is your opinion of my last article?

Professor: There is a great deal in it that is new, and a great deal

that is tme...

Post-graduate: Do you really mean...

Professor: ...but it unfortunately happens that those portions

which are new are not tme, and those which are tme

are not new.

TEXT 7

Before you read

1. Comment on the statement: “Every physical system has its limits.”

2. Now read the text and determine its main points.

Challenge to Our Darwinian Durability

Anthropogenic changes to terrestrial and maritime ecological sys­

tems in the last century have caused environmental transformations

normally associated with geological time scales. Plants and animals

once thought to be inexhaustibly plentiful are currently being lost at

22

Section 1

an unprecedented rate, and nowhere is the impact of human activity

more alarming than in the oceans. Creatures like horseshoe crabs and

sharks, which have endured meteoric cataclysms on their watch, now

face the most serious threat ever to their survival —human beings who

are blithely turning them into plant fertilizer and steak.

Until recently, the scientific community has been reluctant to pro­

actively engage in policy discussions about the issues that will ultimately

determine the long-term viability of people on this planet. Underlying

this not altogether surprising situation are two forces: First, technical

academy has a somewhat parochial view of what it means to be a scien­

tist, and it generally frowns upon members of the establishment who

stray very far from conventional “notions of pure or applied research.”

Second, there is some element of tmth to the popular perception of the

bespectacled, bookish, and socially awkward natural philosopher, whose

heavily laden arguments sound clumsy to the public at large. The eco­

logical systems of the planet, especially those near the bottom of the

food chain, where solar energy is first fixed into convertible sugars and

proteins, are understood only macroscopically at best. Although partic­

ular representatives from other levels of the hierarchy are well studied,

there is an unsettling dearth of knowledge concerning the dependencies

and interdependencies of pelagic fauna and flora. That humans are irre­

vocably influencing these links is undisputed; the only remaining ques­

tion is the long-term implication of our reliance upon these organisms.

The ability of the seas to hold as much as 50 times more carbon

dioxide than the atmosphere is a function of temperature, which is

slowly but steadily increasing. The release of 2% of the carbon dioxide

currently dissolved in the ocean would almost double its concentra­

tion in the atmosphere, thereby reinforcing the greenhouse cycle by

warming the planet even more.

Meanwhile the polar ice caps are slowly melting, and ocean levels

are rising along with the temperature. Although small changes are

troubling, rational worst-case scenarios of the economic impact of this

kind of sea change are mind-boggling. And that is just the carbon di­

oxide part of the story. Confounding subtexts address the nasty byprod­

ucts created in the manufacturing of plastic from petroleum, the nox­

ious fumes generated when we bum the plastic, and the fish, turtles,

birds, and dolphins that are strangled by the bits we throw away.

23

R eading and Speaking

Apparently, most people are simply not aware of the wrenching

harm we inflict upon the ocean by overfishing, dumping toxic chemi­

cals, sinking radioactive submarines and oil platforms, and disposing

of raw sewage. Point sources can be diluted, the wind and currents can

help mix down dangerous substances, and some unusual kinds of bac­

teria even thrive on the scum of our earth. But every physical system —

even one as seemingly large as the ocean —has its limits, and we are

rapidly approaching the threshold of its ability to heal itself in any time

frame of interest to ten generations of human beings. This is about

how long it takes for a plastic trash bag to decompose in the salty sea.

Some stuff never will.

Discussion

1. Give reasons for entitling the text “Challenge to our Darwinian

Durability.”

2. Give arguments for or against the statement: “We are rapidly ap­

proaching the threshold of ecological catastrophe.”

3. Name the burning ecological problems that people have created

on our planet. How do you see the ways for their solution?

For Fun

Comment on the following joke:

Post-graduate: I hear you said my new article was the worst I ever wrote.

Professor: No, I didn’t. I said it was the worst article I ever read.

Section 2

Reading and Summarizing Information

Before writing a paper it is vitally important to be able to read,

understand and summarize information gathered from various sources.

Often the title of an article will give the reader insight into the paper’s

content, but further reading and analysis is necessary to understand

the major points of the article.

To avoid troubles in evaluating a paper it is recommended to read:

• the title, concentrating on key words that show relevance of the

paper to a certain topic;

• an abstract which helps you decide if a paper satisfies your specific

needs;

• the opening and the closing paragraphs which prove relevance of

the paper to your study.

TASK:

Choose a paper from a journal and decide whether it is re­

lated to the subject of your research. What makes you think

that it is relevant to your topic?

The following papers may be used to practise reading and summa­

rizing information.

TEXT 1

1. Read the title of the paper to know what it deals with.

2. Read the paper careftdly to know its content in more detail and complete the tasks

that follow.

Kaiie and Haus Receive National Medal of Science

(1)

Eight scientists received the 1995 U.S. National Medal of

ence, including Isabella Karle from the Naval Research Laboratory

(NRL) and Hermann Haus from the Massachusetts Institute of Tech­

R eading and Sum m arizing Inform ation

25

nology (MIT). The medal is awarded annually by the President of the

United States in special recognition of outstanding contributions in

science and engineering, many of which have directly enhanced long­

term economic growth and improved standards of living.

(2) Karle’s pioneering X-ray analysis of complex crystal and mo­

lecular structures has profoundly affected the disciplines of organic

and biological chemistry. Her work has elucidated the crystal structures

of numerous complex organic substances, natural products, photorearrangement products, biologically active molecules, ionophores,

peptides containing many residues and supramolecular assemblies,

which have significance in synthetic chemistry, medical drug design,

materials design, reaction mechanisms, ion channel formation, mo­

lecular modeling programs, and energy calculations.

(3) Karle’s method systematized analyses that were formerly te­

dious and frustrating. From a small number of simple structure analy­

ses published in the 1960s, her procedure has led to the analysis and

publication of many thousands of structures of complicated molecules

annually. All the present computerized programs for X-ray structure

analyses are based on Karle’s fundamental work, known as the Sym­

bolic Addition Procedure. Karle has also identified and determined

the structures of a number of complex substances of chemical and bio­

medical significance.

(4) Her procedures have been adopted worldwide and have con­

tributed to the output of crystal structure analyses. More than 10,000

analyses are now published annually, compared to about 150 annually

in the early 1960s.

(5) Haus’s research and teaching in quantum optics have enabled

scientists to make significant advances in eye surgery and instrumenta­

tion, as well as fiber optics communications. His work ranges from

fundamental investigations of quantum uncertainty as manifested in

optical communications to the practical generation of ultrashort op­

tical pulses (10,000 times shorter than a nanosecond).

(6) Fiber optical undersea cables providing rapid voice and data

communications among the United States, Europe, and Asia are ben­

eficiaries of the pioneering investigations of Haus and fellow research­

ers at AT&T Bell Laboratories and Nippon Telegraph and Telephone

Research Laboratories, which developed the “solution” method of

26

Section 2

transmission. Their work opens new possibilities for transmitting voice

and data signals across an ocean without repeaters, thus simplifying

the method and enabling higher rates of signal transmission.

Tasks

1. Name the paragraphs describing the contribution to science made

by Isabella Karle.

2. Name the paragraphs describing the contribution to science and

engineering made by Herman Haus.

3. Thoroughly read paragraph 1 and define its main point.

4. Thoroughly read paragraphs 2, 3, 4 and condense their content.

5. Thoroughly read paragraphs 5, 6 and condense their content.

6. Summarize paragraph 1 in no more than two sentences. Begin with:

The paper reports o n ...

7. Compress paragraphs 2,3 and 4 into a statement using the phrases:

A carefiil account is given to ...

It is reported that...

The paper claims that...

8. Compress paragraphs 5 and 6 into a statement using the phrases:

Much attention is given to ...

It is claimed that...

The paper points out that...

9. Summarize the content of the paper.

TEXT 2

1. Read the title of the paper to understand its main point

2. Read the paper carefully to know its content in more detail and complete the tasks

that follow.

Japan Stores Sunlight in Crystals

(1)

Japan has managed to store the sun’s energy for 61 days in

important development in the use of solar power. Scientists have pro­

duced a stable chemical compound to store the energy and claimed it

as a world breakthrough after 20 years of research.

R eading and Sum m arizing Inform ation

27

(2) Led by Professor Zenichi Yoshida of the engineering depart­

ment of Kyoto University, they claim the compound will overcome the

greatest hurdle to the practical use of solar power: the production of

energy when the sun is not shining.

(3) The new compound has not been named but takes the form of

a yellow crystal, which is made by combining a petroleum derivative,

called norbomadiene, with methyl radicals and a substance named

cyano.

(4) It changes its molecular structure when exposed to sunshine.

Professor Yoshida said that when a small catalyst of silver was applied

to it, the substance reverted to its original structure, generating heat at

any required moment.

(5) If produced in liquid form, the compound would retain the

energy for 61 days without a boost of sunshine.

(6) “The temperature of the compound does not rise when solar

energy is stored. The energy takes the form of molecular change at

normal temperatures. In this way, energy is not lost through the dissi­

pation of heat,” a spokesman for Kyoto University explained.

(7) Professor Yoshida said initial tests showed that 2.2 pounds of

the substance would conserve 92,000 calories. The research team said

a solar heater with a surface of a square meter could store 85 million

calories of energy a year. The compound could also be transported while

it stored energy. If the compound was produced in solid form, it could

store energy for indefinite periods if the silver catalyst was not applied.

However, it would have to be produced in a more impure liquid form

for practical use.

(8) Professor Yoshida said the new compound could be used to

store energy for heating, cooling and eventually the generation of elec­

trical power. There would be little wastage and no pollution.

Tasks

1. Read the text and find the paragraphs that deal with:

a) the importance of the scientific advance in storing the sun’s

energy;

b) the characteristics of the new compound produced in Japan;

c) the possible practical applications of the new compound.

28

Section 2

2. Present the information on the importance of the scientific advance

in storing the sun’s eneigy. Begin with:

The paper considers a new advance in storing the sun’s energy in

Japan. It emphasizes that...

3. Present the information on the characteristics of the new compound

produced in Japan. Use the phrases:

The paper gives a detailed description of the new compound. It is

reported that...

4. Present the information on the possible practical applications of

the new compound. Use the phrases:

Attention is also given to the practical advantage of the compound.

It is claimed that...

5. Summarize the content of the paper.

TEXT 3

1. Read the title of the paper to know what it deals with.

2. Read the paper careM y to know its content in more detail and complete the tasks

that follow.

Viral Soup

(1) Researchers studying the bacteria that live in the ocean have

long been troubled by one question: Given the abundance of the bac­

teria, and given that their marine predators can’t possibly consume

them as fast as they grow, why haven’t bacterial colonies saturated the

oceans? Two recent studies may have turned up the answer: the bacte­

ria are held back by bacteria-killing viruses whose numbers are thou­

sands of times greater than once thought.

(2) The first study was conducted over the past two years by ecologists

from the University of Bergen in Norway Traveling to remote patches of

ocean, they collected samples of unpolluted water, which they then spun

at 100,000 times the force of gravity —more centrifugal kick than had ever

been used before in similar experiments. With an electron microscope,

they counted the virus particles that were sorted out and found that a mil­

liliter of water —about one-fifth of a teaspoon —can contain 100 million

viruses. Previous estimates had put the count at less than 10,000.

R eading and Sum m arizing Inform ation

29

(3) The second study, by biological oceanographers Jed Fuhrman and lita Proctor of the University of Southern California, was

designed to see if these viruses are infecting a large number of ocean­

ic bacteria. Fuhrman and Proctor concentrated the organic matter

in 25 gallons of seawater down to a pinhead-size pellet. They then

used a diamond-edged knife to slice the pellet into sections fourmiUionths of an inch thick, each containing hundreds of thousands

of bacteria. When they examined the sections under the microscope,

they found a virtual viral epidemic —suggesting that viruses could be

killing up to 70 percent of the oceans’ bacteria.

(4) The researchers believe that this scenario explains how na­

ture keeps its bacteria under control. But what controls the viruses?

“So many things kill viruses in the lab,” Proctor said, “that we have

to assume something’s killing them in the sea. We just don’t know

what.”

Tasks

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Name the paragraphs that present the research problem.

Name the paragraphs that describe the research results.

Name the paragraphs that contain the research conclusion.

Thoroughly read paragraph 1 and describe its main point.

Thoroughly read paragraphs 2, 3 and describe the research results.

Thoroughly read paragraph 4 and describe the main research con­

clusion.

7. Condense paragraph 1 using the phrases:

The paper deals with the problem of...

The purpose of the research is to ...

8. Present the content of paragraphs 2 and 3 using the phrases:

The paper describes the experiments in detail...

It is reported that...

9. Compress paragraph 4 into a statement using the phrases:

The research results showed that...

The research has given rise to ...

10. Summarize the content of the paper.

30

Section 2

TEXT 4

1. Read the title of the paper to understand its main point.

2. Read the paper carefully to know what information it provides and complete the

tasks that follow.

Energy-Converting Plastic Film

(1) More than 100 years ago, the French scientists Pierre and

Jacques Curie observed that certain crystalline materials, such as quartz,

produced an electrical charge when subjected to pressure. For decades

thereafter this reversible energy conversion phenomenon known as

piezoelectricity has found a number of limited applications in sonar

and radio equipment, scientific instruments and, perhaps most famil­

iarly, wristwatches. Recently, piezoelectric properties have been de­

signed into thin, pliable plastic films that resemble transparent kitchen

wrapping material. The versatility of this material promises to open up

a wide variety of new piezoelectric applications for consumer and in­

dustrial products.

(2) One of the new piezoelectric films, developed over the last

eight years by the Pennwalt Corp. of Philadelphia, Pa., is called Kynar Piezo Film. Though it’s lightweight and pliant, the material is

actually a rugged engineering plastic that has been specifically treat­

ed to give it piezoelectric properties. As a replacement for electro­

magnetic switches, the piezoelectric film offers a number of advan­

tages. It can be cut, bent and formed into almost any shape or size.

Perhaps best of all, since it converts one form of energy into another,

the piezoelectric film can be used without an external power source

in many applications.

(3) Currently, Kynar Piezo Film and others like it are finding ap­

plications in lightweight, miniature speakers and microphones for

audio equipment and flat switches on office-equipment and controlpanel keyboards. Kynar Piezo Film has another property that makes

it unique: It is also pyroelectric, which means that it produces elec­

trical current when exposed to heat. As such, it is ideal for use in

security equipment such as fire detectors or body-heat-sensing bur­

glar alarms.

R eading and Sum m arizing Inform ation

31

(4)

Yet the greatest range of applications for piezoelectric films

tainly lies ahead. Pennwalt officials see future uses in ocean-wave and

wind-power electrical generators, inexpensive and disposable bloodpressure cuffs — even a highly sensitive sonar-detecting hull coating

for submarines. Right now research is being conducted on the use of

piezoelectric film as a tactile sensor for robots. Ultimately, Pennwalt

officials claim, piezoelectric film may be the key to providing a bionic

sense of touch to artificial skin for humans.

Tasks

1. Read paragraph 1 and find the sentence that explains piezoelec­

tricity as a phenomenon.

2. Read paragraph 2 and find the sentence that develops the idea of

the advantages of piezoelectric films.

3. Read paragraph 3 and find the sentence that names the property

that makes piezoelectric films unique.

4. Thoroughly read the paper and name the range of applications for

piezoelectric films.

5. Summarize the content of the paper using the phrases:

The paper provides information o n ...

The paper defines the phenomenon of...

An attempt is made to ...

The paper points out...

The paper claims that...

TEXT 5

1. Read the title of the paper to know what it is about.

2. Read the paper carefiilly to know its content in more detail and complete the tasks

that follow.

Why Care About Global Warming?

(1)

At first glance, global warming may seem like a great idea. S

bathing or eating fiesh strawberries in the dead of winter sounds ap­

pealing to those who live in cold climates.

32

Section 2

(2) But the reality is more complicated. We don’t know exactly

what will happen in a warmer world —what the impact will be —nor do

we know exactly where or when the effects of warmer weather will hit

the hardest. Yet it’s fair to say that we have a pretty good idea of what’s

to come.

(3) Scientists and researchers from various fields tell us that the

possible effects of climate change could be far-reaching, and, in some

cases, cause serious problems. In the words of Pennsylvania State Uni­

versity professor Brent Yamal, “I know of no scientific area of study

that has more consensus than the field of global warming.”

(4) Scientists’ measurements indicate that the average global tem­

perature has increased by about one degree Fahrenheit in the past cen­

tury. It may seem hard to believe that such a small increase could affect

the way we live. But during the Ice Ages, the average global tempera­

ture was only 9-12 degree Fahrenheit colder than the temperatures to­

day.

(5) Scientists believe that a continuing temperature rise may lead

to increased human illnesses and deaths, worsening erosion of beach­

es, and causing the extinction of animal and plant species.

(6) How can global warming affect health? Well, warmer tempera­

tures encourage the proliferation of disease-carrying mosquitoes and

thus could lead to an increase in infectious diseases such as encephali­

tis, malaria, and dengue-fever. Rising temperatures also could increase

pollution and reduce air quality in heavily populated urban areas, lead­

ing to an increase in respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

(7) In addition, higher temperatures contribute to the melting of

glaciers and the expansion of ocean water as it heats up, causing sea

level to rise. Higher sea levels erode beaches, increase storm surges,

lead to a loss of wetlands, and can compromise freshwater supplies by

introducing saltwater.

(8) Climate change also is likely to increase the number of species

listed as threatened or endangered. For example, when droughts are

prolonged, the habitats required by ducks, frogs, and many other spe­

cies dependent on ponds and streams decline.

(9) The effect of climate change on agriculture maybe varied. Yields

are projected to increase in some regions for some crops and decrease

in others. However, large areas of the United States —particularly the

R eading and Sum m arizing Inform ation

33

Great Plains —may face moderate to severe drying of the soil as more

frequent droughts occur.

(10) John Magnuson, a professor of zoology at the University of

Wisconsin-Madison, points out, for example, that an expected decline

in rainwater runoffunder global warming “would have effects on drink­

ing water availability, irrigation, and water levels in the Great Lakes.”

(11) Chances are that all of these effects will have economic impli­

cations. Among them are expensive clean-up operations from the pos­

sible increase in extreme weather, such as more frequent and heavy

rainfalls in some regions, causing rivers to flood. A rise in sea level may

mean billions of dollars in property damage from worsening storms

and increased flooding along shorelines.

(12) Although it is true that we cannot say for certain what global

warming will bring, we know enough to take sensible measures. Harold

Frumkin, a professor at Emory University in Atlanta, may have put it

best when he said, “The costs of acting are bearable. The risks of not

acting are unbearable.”

Tasks

1. Name the paragraphs describing the possible dangerous effects of

global warming.

2. Name the paragraphs that do not provide information about glo­

bal warming impact on people’s health, soil, animals, plants and

economy.

3. Thoroughly read the paragraphs describing the dangerous effects

of global warming and define their main points.

4. Summarize the content of the paper using the phrases:

The paper suggests the problem o f . . . .

The effects o f... on ... are considered.

The paper covers such points a s ....

It is claimed that....

The paper also claims that....

The paper points out that....

Attention is given to ....

Attention is also concentrated on ....

34

Section 2

TEXT 6

1. Read the title of the paper to know its topic.

2. Read the paper carefully to know its content in more detail and complete the tasks

that follow.

Virtual Electron Microscope Laboratory Demonstrated

(1) Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkley N ational Laboratory

(LBNL) is setting up its high voltage electron microscope so that it

is accessible to users on the Internet. The laboratory has created a

set of interactive, online computing tools that will allow scientists

to manipulate the instrument, conduct experiments, and view im­

ages online from their offices.

(2) To sidestep the time lags that occur across computer net­

works, computer scientist Bahram Parvin’s team is automating on­

site the positioning and focusing of the microscope. This is being

made possible through the development of advanced computer vi­

sion algorithms.

(3) Parvin said, “You start with what to a computer is an indis­

criminate field. You then detect and lock onto objects of interest.

This is computer vision. Very soon, from a remote location, com­

puter vision will self-calibrate the microscope, autofocus it, and

compensate for thermal drift. Underlying this is a complex package

of algorithms dealing with shape analysis, background measure­

ments, wavelet transform, and servo-loop control. Essentially,

though, we are making the microscope smarter, making it do intu­

itively what users would have to do on their own.”

(4) At the Microscopy Society of America’s annual international

meeting in Kansas City, LBNL scientists demonstrated the process

of controlling the in situ electron microscope by computer. They

heated an advanced alloy specimen and observed the ensuing pro­

gression of structural changes on the computer monitor.

(5) The researchers’ goal is for experimenters at remote loca­

tions to control the microscope to change magnification, scan the

sample, alter its orientation, and trigger a range of experimental

conditions.

R eading and Sum m arizing Inform ation

35

Tasks

1. Name the paragraph dealing with the technological advance in

computer science.

2. Name the paragraph concerned with the possibilities provided by

the virtual electron microscope for experimenters at remote loca­

tions.

3. Summarize the content of the paper using the phrases:

The paper reports on ....

Much attention is given to ....

It is reported that....

It is pointed out that....

The paper claims that....

The paper is of interestfo r ....

TEXT 7

1. Read the title of the papa* to know what it deals with.

2. Read the paper careM y to know its content in more detail and complete the tasks

that follow.

Simulations Predict Failure Mechanisms of Lubricants

in Nanometer-Scale Devices

(1) Using supercomputers to model the complex physical processes

involved, the researchers studied the behavior of a thin-film hexadecane

(CjgH^) lubricant flowing between two gold disks sliding past each other

at a relative velocity of 10 m/s. Under these conditions, the flow of

liquid lubricant through the narrow space between the surfaces creates

pressure high enough to cause temporary elastic deformation of the

disks. Repeated deformation could ultimately lead to fatigue failure

and to the development of pits or cracks on the disk surface.

(2) More troubling are the possible effects associated with tiny sur­

face nonuniformities, asperities, that exist on disks that appear to be

smooth.

(3) Landman and colleagues Jianping Gao and W.D. Luedtke stud­

ied three instances in which asperities passed close enough together to

36

Section 2

affect the lubricating film. The first involved a separation of approxi­

mately 17.5 A; the second a “near-overlap” of 4.6 A, and the third a

situation in which the ridges overlapped and collided.

(4) In the first instance, the increased confinement in the region

between the approaching asperities caused the lubricant to organize

into distinct layers that resembled the ordered structure of a solid. As

the pressure continued to increase, the viscosity of the liquid film in­

creased as the molecules flowed out of the gap one layer at a time. This

quantized layered structure of the lubricant molecules caused an oscil­

lation in the force required to maintain the relative sliding velocity be­

tween the disk surfaces.

(5) In the second instance of a much smaller separation, the pres­

sure imposed on the lubricant became large enough to elastically de­

form and flatten the asperities, helping to smooth the surface of the

disks. Pressures of 200,000 to 300,000 atm could be created as the lu­

bricant is squeezed out of the gap.

(6) In the third instance, all of the lubricant molecules were forced

out of the gap and the asperities collided, briefly forming a metallic

junction and transferring material before separating. The high pres­

sures created by the collisions caused the liquid lubricant to change

into a near-solid phase.

(7) Landman said, “You come to the point at which the lubricant

molecules are arrested. There is not enough time for them to escape

the confined region that is being produced. This can cause the lubri­

cant to undergo a phase change to an ultra viscous fluid or a soft solid.

Under extreme circumstances, the liquid can become a glassified solid

that develops a significant resistance to shear. This could bring about

seizure and a disk crash.”

(8) Another potentially harmful effect is the cavitation that can

occur after the asperities collide. When they separate as the disks con­

tinue their rotation, lubricant molecules are slow to fill the widening

gap, creating a cavitation phenomena that may be harmful because,

according to Landman, “their collapse releases sufficient energy to

damage the surface through the propagation of supersonic shock waves

and the release of heat.”

(9) In addition to the cases of nonuniform surface asperities, Land­

man said the normal starting and stopping of a disk drive could also

R eading and Sum m arizing Inform ation

37

alter the space between moving surface and create increased pressure.

As render-heads are placed closer and closer to disk surfaces to gain

spatial resolution, this problem could become more of concern. In the

process of deformation and collision, the action of the elastohydrodynamic lubrication may liberate wear particles. Landman does not

know, yet, how these particles may affect the device and degrade the

lubricant.

Tasks

1. Name the paragraphs dealing with predictions of die complex phys­

ical processes in ultra-thin films of the organic lubricants used in

nanometer-scale devices.

2. Name the paragraphs that describe the physical processes in lubri­

cants under different conditions.

3. Find the conclusive paragraph in which phase change in lubricants

is accounted for.

4. Find the paragraph concerned with a cavitation phenomena.

5. Summarize the content of the paper using the phrases:

The paper is about....

It is recognized that....

The results o f ... are presented.

It isfound that... .

The paper touches upon ....

Section 3

SPEAKING

1. Field of Science and Research

Active Vocabulary

to do/to carry on/to carry out/to conduct research

to contribute to/to make a contribution to

to influence/to affect / to have an effect on/upon

to study/to make studies/to investigate/to explore

to put forward an idea

to suggest an idea/a theory/a hypothesis

to advance/to develop/to modify a theory

to predict/to forecast/to foresee

to accumulate knowledge

field of science/research

a new area of research

current branch/field of research

latest/recent achievements/developments/advances

a(an) outstanding/prominent/world-known scientist/researcher

Tasks

A.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Answer the questions:

What is your field of science/research?

What are the current issues in your field of science/research?

Have new areas of research appeared in recent years?

What is your particular area of research?

What are the latest achievements in your field of science/research?

Have many fundamental discoveries been made in your field of

science/research?

7. Can you name some outstanding researchers in your field of sci­

ence? What contribution have they made?

39

Speaking

8. Do achievements in your branch of science/research influence ev­

eryday life? In what way?

9. What further developments can you predict in your field of sci­

ence/research?

B.

Complete the sentences which contain the words from the Active Vocabulary

Section. Speak about your field of science/research.

1. I do research in the field o f....

2. It is the science/a comparatively new branch of science that studies...

3. The field of science/research that I’m concerned with gathers

knowledge about...

4. Major developments include advances in ....

5. Remarkable advances have been made in ....

6. The branches of science contributing a lot to progress in my field

of research are ....

7. My current field of science/research is ....

8. It’s difficult/not difficult to foresee/forecast/predict....

С Wbrk in pairs.

Ask for and give information on your field of science and research.

D. Act out the situation.

Two students are discussing the progress made in their fields of sci­

ence and its influence on life today.

2. Research Problem

Active Vocabulary

to be due to

to arise from

to increase considerably

to be the subject of special/particular interest

to be studied comprehensively/thoroughly/extensively

to be only outlined

to be mentioned in passing

to be concerned with/to be engaged in the problem of

to deal with/to consider the problem of

40

Section 3

to be interested in

to be of great/little/no interest/impoitance/significance/value/use

to take up the problem

to work on the problem

to follow/to stick to the theoiy/hypothesis/concept

to postulate

to differ/to be different from

a lot of/little/no literature is available on the problem

the reason for the interest in the problem is ...

Tasks

A. Answer the questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

What is your research problem?

What is of special interest in the problem of your research?

What is the subject of your research?

Why has the interest in this problem increased considerably in re­

cent years?

5. Do you follow/stick to any theoiy/hypothesis/concept? What is it?

6. What concept is your research based on?

7. How does your research differ from other studies of the same prob­

lem?

8. Is there much literature available on your research problem?

9. Is your research problem described comprehensively/thoroughly/

extensively in literature?

10. Is the problem only outlined or mentioned in passing?