1) Lexicology, its object and aims of research.

L deals with the lexicon of a La, studies its development,

structure and use. This study can be oriented in many ways

towards the synchronic description of the vocabulary of a

particular La (certain historical level of La development);

towards the study of diachronic or historical processes and laws

which govern the development of the vocabulary (word

evolution & development); towards the comparative or

contrastive analysis of the lexicon of a particular La; towards

the research of the functional properties of the vocabulary units

etc.

The object of lexicology is lexicon, or L vocabulary. The

description of the lexicon can have applied purposes: the major

domains of application are the science of compiling

dictionaries, teaching Las, second La acquisition,

computerization.

Sharing its object with other linguistic disciplines lexicology

nevertheless concentrates on its own aspects of analysis: the

structure, semantics and function of the lexicon, thus forming a

special branch of linguistic science with its own aims, object of

research and its subject matter.

The aim of English Lexicology is the study and systematic

description of the vocabulary of Present-Day English (origin,

morph structures, world building means, meanings of E words,

standard variants of E).

4) The function of lexical units. Naming processes: causes, ways, types and results.

To solve the problem of the constituents of the lexicon we have to view it from the functional

dynamic point of view. The theory that discusses these problems is known as the theory of

naming (nomination, verbalization, i.e. giving a name to a class of objects, properties,

processes, events). The roots of the naming theory go as far back as ancient times.

The world changes, our knowledge of the world changes makin’ it an ever-present necessity,

a permanent cause for processes of naming to take place.

Together with our understanding of the world our emotional attitudes towards things, events,

or their properties may change thus creating a need for verbalization to express our changed

emotions. Types of causes for naming: 1) social (objective); 2) cognitive (epistemological);

3) psychological (emotional); 4) linguistic causes.

There exist universal ways to appease that hunger for names: Imitation (a name to an object,

event, property or a class of them is given by means of imitation of some property, usually,

the one which is connected with sound (to whisper, roar, bang, murmur in E or шуршать,

шептать, бормотать, etc. in Russian). The results of imitation naming processes pose a very

serious linguistic problem, namely, that of arbitrariness (своевольность), or conventionality

of a name. Коллектив складывается из индивидуумов, а индивиды воспринимают звуки

по разному (atishoo in E, апчхи in Russian).

Semantic derivation (Transfer of Things which seem to have no likeness are given the same

name). E.g. eye is a name for an organ of sight, and eyes of a potato, eye of a needle, the

eye of the tornado, etc., an eye of a peacock (a private eye): a detective. Though first it

appeared as the name of a human organ later on the name was transferred to other objects

and other spheres.

Word derivation (creation of novel names on the basis of names already existent in the word

stock, a most vivid example being word composition). A room – a living room, a bedroom, a

sitting room, a bathroom, a guest-room to express various function of rooms. Here we face

the same problem of arbitrariness: a living-room-гостиная, a bed-room-спальня.

Borrowing. No La is free of borrowings which (militia (L. military service), might come in

different ways, methods (directly or indirectly) and in different shapes (in the form of lexical

items, shaped according to the phonetic, grammatic norms of the La or in the form of

translation (vodka in E. Vodkas, malchiks, etc.), loans (Fr. tete a tete).

Types: Naming processes can be viewed on the basis of interrelations between units

created. Guided by this criterion primary and secondary naming units are distinguished, the

range of which in the naming process leads to differentiation between primary and

secondary types of verbalization or naming processes, direct or indirect types of

verbalization.

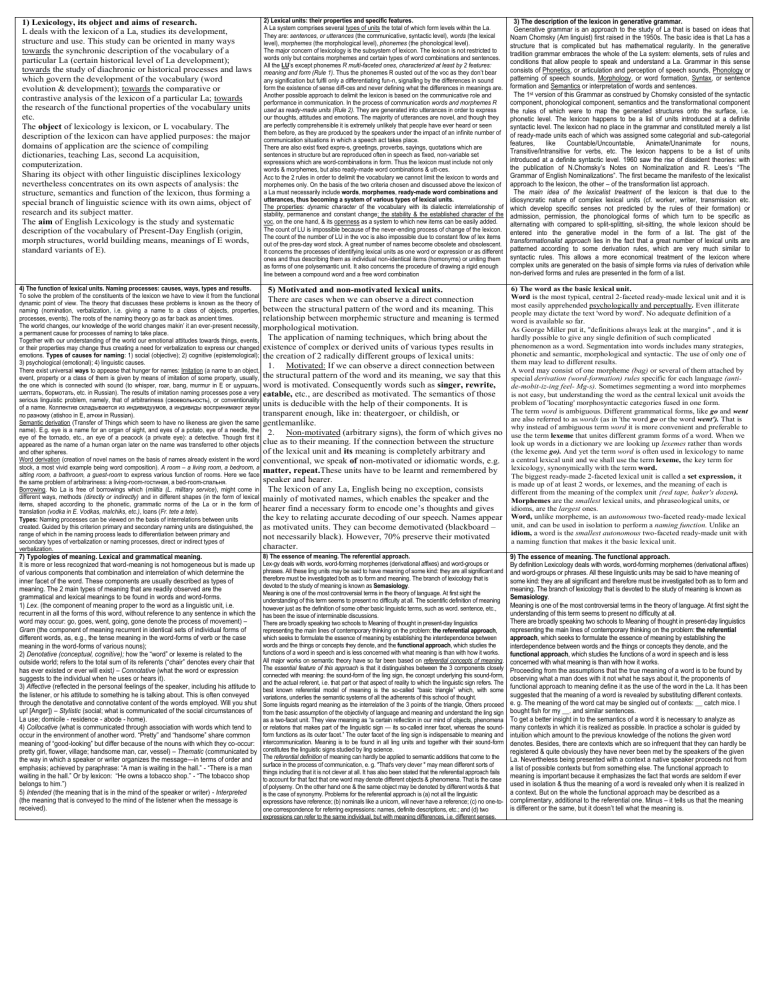

7) Typologies of meaning. Lexical and grammatical meaning.

It is more or less recognized that word-meaning is not homogeneous but is made up

of various components that combination and interrelation of which determine the

inner facet of the word. These components are usually described as types of

meaning. The 2 main types of meaning that are readily observed are the

grammatical and lexical meanings to be found in words and word-forms.

1) Lex. (the component of meaning proper to the word as a linguistic unit, i.e.

recurrent in all the forms of this word, without reference to any sentence in which the

word may occur: go, goes, went, going, gone denote the process of movement) –

Gram (the component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of

different words, as, e.g., the tense meaning in the word-forms of verb or the case

meaning in the word-forms of various nouns);

2) Denotative (conceptual, cognitive); how the “word” or lexeme is related to the

outside world; refers to the total sum of its referents (“chair” denotes every chair that

has ever existed or ever will exist) – Connotative (what the word or expression

suggests to the individual when he uses or hears it).

3) Affective (reflected in the personal feelings of the speaker, including his attitude to

the listener, or his attitude to something he is talking about. This is often conveyed

through the denotative and connotative content of the words employed. Will you shut

up! [Anger]) – Stylistic (social; what is communicated of the social circumstances of

La use; domicile - residence - abode - home).

4) Collocative (what is communicated through association with words which tend to

occur in the environment of another word. “Pretty” and “handsome” share common

meaning of “good-looking” but differ because of the nouns with which they co-occur:

pretty girl, flower, village; handsome man, car, vessel) – Thematic (communicated by

the way in which a speaker or writer organizes the message—in terms of order and

emphasis; achieved by paraphrase: “A man is waiting in the hall.” - “There is a man

waiting in the hall.” Or by lexicon: “He owns a tobacco shop.” - “The tobacco shop

belongs to him.”)

5) Intended (the meaning that is in the mind of the speaker or writer) - Interpreted

(the meaning that is conveyed to the mind of the listener when the message is

received).

2) Lexical units: their properties and specific features.

A La system comprises several types of units the total of which form levels within the La.

They are: sentences, or utterances (the communicative, syntactic level), words (the lexical

level), morphemes (the morphological level), phonemes (the phonological level).

The major concern of lexicology is the subsystem of lexicon. The lexicon is not restricted to

words only but contains morphemes and certain types of word combinations and sentences.

All the LU’s except phonemes R multi-faceted ones, characterized at least by 2 features:

meaning and form (Rule 1). Thus the phonemes R ousted out of the voc as they don’t bear

any signification but fulfil only a differentiating fun-n, signalling by the differences in sound

form the existence of sense diff-ces and never defining what the differences in meanings are.

Another possible approach to delimit the lexicon is based on the communicative role and

performance in communication. In the process of communication words and morphemes R

used as ready-made units (Rule 2). They are generated into utterances in order to express

our thoughts, attitudes and emotions. The majority of utterances are novel, and though they

are perfectly comprehensible it is extremely unlikely that people have ever heard or seen

them before, as they are produced by the speakers under the impact of an infinite number of

communication situations in which a speech act takes place.

There are also exist fixed expre-s, greetings, proverbs, sayings, quotations which are

sentences in structure but are reproduced often in speech as fixed, non-variable set

expressions which are word-combinations in form. Thus the lexicon must include not only

words & morphemes, but also ready-made word combinations & utt-ces.

Acc to the 2 rules in order to delimit the vocabulary we cannot limit the lexicon to words and

morphemes only. On the basis of the two criteria chosen and discussed above the lexicon of

a La must necessarily include words, morphemes, ready-made word combinations and

utterances, thus becoming a system of various types of lexical units.

The properties: dynamic character of the vocabulary with its dialectic interrelationship of

stability, permanence and constant change; the stability & the established character of the

voc, on the one hand, & its openness as a system to which new items can be easily added.

The count of LU is impossible because of the never-ending process of change of the lexicon.

The count of the number of LU in the voc is also impossible due to constant flow of lex items

out of the pres-day word stock. A great number of names become obsolete and obsolescent.

It concerns the processes of identifying lexical units as one word or expression or as different

ones and thus describing them as individual non-identical items (homonyms) or uniting them

as forms of one polysemantic unit. It also concerns the procedure of drawing a rigid enough

line between a compound word and a free word combination

3) The description of the lexicon in generative grammar.

Generative grammar is an approach to the study of La that is based on ideas that

Noam Chomsky (Am linguist) first raised in the 1950s. The basic idea is that La has a

structure that is complicated but has mathematical regularity. In the generative

tradition grammar embraces the whole of the La system: elements, sets of rules and

conditions that allow people to speak and understand a La. Grammar in this sense

consists of Phonetics, or articulation and perception of speech sounds, Phonology or

patterning of speech sounds, Morphology, or word formation, Syntax, or sentence

formation and Semantics or interpretation of words and sentences.

The 1st version of this Grammar as construed by Chomsky consisted of the syntactic

component, phonological component, semantics and the transformational component

the rules of which were to map the generated structures onto the surface, i.e.

phonetic level. The lexicon happens to be a list of units introduced at a definite

syntactic level. The lexicon had no place in the grammar and constituted merely a list

of ready-made units each of which was assigned some categorial and sub-categorial

features, like Countable/Uncountable, Animate/Unanimate for nouns,

Transitive/Intransitive for verbs, etc. The lexicon happens to be a list of units

introduced at a definite syntactic level. 1960 saw the rise of dissident theories: with

the publication of N.Chomsky’s Notes on Nominalization and R. Lees’s “The

Grammar of English Nominalizations”. The first became the manifesto of the lexicalist

approach to the lexicon, the other – of the transformation list approach.

The main idea of the lexicalist treatment of the lexicon is that due to the

idiosyncratic nature of complex lexical units (cf. worker, writer, transmission etc.

which develop specific senses not predicted by the rules of their formation) or

admission, permission, the phonological forms of which turn to be specific as

alternating with compared to split-splitting, sit-sitting, the whole lexicon should be

entered into the generative model in the form of a list. The gist of the

transformationalist approach lies in the fact that a great number of lexical units are

patterned according to some derivation rules, which are very much similar to

syntactic rules. This allows a more economical treatment of the lexicon where

complex units are generated on the basis of simple forms via rules of derivation while

non-derived forms and rules are presented in the form of a list.

5) Motivated and non-motivated lexical units.

There are cases when we can observe a direct connection

between the structural pattern of the word and its meaning. This

relationship between morphemic structure and meaning is termed

morphological motivation.

The application of naming techniques, which bring about the

existence of complex or derived units of various types results in

the creation of 2 radically different groups of lexical units:

1. Motivated: If we can observe a direct connection between

the structural pattern of the word and its meaning, we say that this

word is motivated. Consequently words such as singer, rewrite,

eatable, etc., are described as motivated. The semantics of those

units is deducible with the help of their components. It is

transparent enough, like in: theatergoer, or childish, or

gentlemanlike.

2. Non-motivated (arbitrary signs), the form of which gives no

clue as to their meaning. If the connection between the structure

of the lexical unit and its meaning is completely arbitrary and

conventional, we speak of non-motivated or idiomatic words, e.g.

matter, repeat.These units have to be learnt and remembered by

speaker and hearer.

The lexicon of any La, English being no exception, consists

mainly of motivated names, which enables the speaker and the

hearer find a necessary form to encode one’s thoughts and gives

the key to relating accurate decoding of our speech. Names appear

as motivated units. They can become demotivated (blackboard –

not necessarily black). However, 70% preserve their motivated

character.

6) The word as the basic lexical unit.

Word is the most typical, central 2-faceted ready-made lexical unit and it is

most easily apprehended psychologically and perceptually. Even illiterate

people may dictate the text 'word by word'. No adequate definition of a

word is available so far.

As George Miller put it, "definitions always leak at the margins" , and it is

hardly possible to give any single definition of such complicated

phenomenon as a word. Segmentation into words includes many strategies,

phonetic and semantic, morphological and syntactic. The use of only one of

them may lead to different results.

A word may consist of one morpheme (bag) or several of them attached by

special derivation (word-formation) rules specific for each language (antide-mobit-iz-ing feel- Mg-s). Sometimes segmenting a word into morphemes

is not easy, but understanding the word as the central lexical unit avoids the

problem of 'locating' morphosyntactic categories fused in one form.

The term word is ambiguous. Different grammatical forms, like go and went

are also referred to as words (as in 'the word go or the word went'). That is

why instead of ambiguous term word it is more convenient and preferable to

use the term lexeme that unites different gramm forms of a word. When we

look up words in a dictionary we are looking up lexemes rather than words

(the lexeme go). And yet the term word is often used in lexicology to name

a central lexical unit and we shall use the term lexeme, the key term for

lexicology, synonymically with the term word.

The biggest ready-made 2-faceted lexical unit is called a set expression, it

is made up of at least 2 words, or lexemes, and the meaning of each is

different from the meaning of the complex unit {red tape, baker's dozen).

Morphemes are the smallest lexical units, and phraseological units, or

idioms, are the largest ones.

Word, unlike morpheme, is an autonomous two-faceted ready-made lexical

unit, and can be used in isolation to perform a naming function. Unlike an

idiom, a word is the smallest autonomous two-faceted ready-made unit with

a naming function that makes it the basic lexical unit.

8) The essence of meaning. The referential approach.

Lex-gy deals with words, word-forming morphemes (derivational affixes) and word-groups or

phrases. All these ling units may be said to have meaning of some kind: they are all significant and

therefore must be investigated both as to form and meaning. The branch of lexicology that is

devoted to the study of meaning is known as Semasiology.

Meaning is one of the most controversial terms in the theory of language. At first sight the

understanding of this term seems to present no difficulty at all. The scientific definition of meaning

however just as the definition of some other basic linguistic terms, such as word. sentence, etc.,

has been the issue of interminable discussions.

There are broadly speaking two schools to Meaning of thought in present-day linguistics

representing the main lines of contemporary thinking on the problem: the referential approach,

which seeks to formulate the essence of meaning by establishing the interdependence between

words and the things or concepts they denote, and the functional approach, which studies the

functions of a word in speech and is less concerned with what meaning is than with how it works.

All major works on semantic theory have so far been based on referential concepts of meaning.

The essential feature of this approach is that it distinguishes between the 3 components closely

connected with meaning: the sound-form of the ling sign, the concept underlying this sound-form,

and the actual referent, i.e. that part or that aspect of reality to which the linguistic sign refers. The

best known referential model of meaning is the so-called “basic triangle” which, with some

variations, underlies the semantic systems of all the adherents of this school of thought.

Some linguists regard meaning as the interrelation of the 3 points of the triangle, Others proceed

from the basic assumption of the objectivity of language and meaning and understand the ling sign

as a two-facet unit. They view meaning as “a certain reflection in our mind of objects, phenomena

or relations that makes part of the linguistic sign — its so-called inner facet, whereas the soundform functions as its outer facet.” The outer facet of the ling sign is indispensable to meaning and

intercommunication. Meaning is to be found in all ling units and together with their sound-form

constitutes the linguistic signs studied by ling science.

The referential definition of meaning can hardly be applied to semantic additions that come to the

surface in the process of communication, e. g. "That's very clever " may mean different sorts of

things including that it is not clever at all. It has also been stated that the referential approach fails

to account for that fact that one word may denote different objects & phenomena. That is the case

of polysemy. On the other hand one & the same object may be denoted by different words & that

is the case of synonymy. Problems for the referential approach is (a) not all the linguistic

expressions have reference; (b) nominals like a unicorn, will never have a reference; (c) no one-toone correspondence for referring expressions: names, definite descriptions, etc.; and (d) two

expressions can refer to the same individual, but with meaning differences, i.e. different senses.

9) The essence of meaning. The functional approach.

By definition Lexicology deals with words, word-forming morphemes (derivational affixes)

and word-groups or phrases. All these linguistic units may be said to have meaning of

some kind: they are all significant and therefore must be investigated both as to form and

meaning. The branch of lexicology that is devoted to the study of meaning is known as

Semasiology.

Meaning is one of the most controversial terms in the theory of language. At first sight the

understanding of this term seems to present no difficulty at all.

There are broadly speaking two schools to Meaning of thought in present-day linguistics

representing the main lines of contemporary thinking on the problem: the referential

approach, which seeks to formulate the essence of meaning by establishing the

interdependence between words and the things or concepts they denote, and the

functional approach, which studies the functions of a word in speech and is less

concerned with what meaning is than with how it works.

Proceeding from the assumptions that the true meaning of a word is to be found by

observing what a man does with it not what he says about it, the proponents of

functional approach to meaning define it as the use of the word in the La. It has been

suggested that the meaning of a word is revealed by substituting different contexts.

e. g. The meaning of the word cat may be singled out of contexts: __ catch mice. I

bought fish for my __. and similar sentences.

To get a better insight in to the semantics of a word it is necessary to analyze as

many contexts in which it is realized as possible. In practice a scholar is guided by

intuition which amount to the previous knowledge of the notions the given word

denotes. Besides, there are contexts which are so infrequent that they can hardly be

registered & quite obviously they have never been met by the speakers of the given

La. Nevertheless being presented with a context a native speaker proceeds not from

a list of possible contexts but from something else. The functional approach to

meaning is important because it emphasizes the fact that words are seldom if ever

used in isolation & thus the meaning of a word is revealed only when it is realized in

a context. But on the whole the functional approach may be described as a

complimentary, additional to the referential one. Minus – it tells us that the meaning

is different or the same, but it doesn’t tell what the meaning is.

28) The derivation device: zero-derivation, non-affixal word

formation, conversion, morphological, syntactic, morphologicalsyntactic way of word formation.

Zero-derivation – the way of word building without use of special

derivational affixes; type of transposition when the transition of a word

takes place when one word is used without any changing as a

representative of another class of words (salt – to salt).

Non-affixal way of forming words or Root formation is when a

certain stem is used for the formation of a different word of a different

part of speech without a derivational affix being added (to sing —

song; to feed — food; full — to fill).

Conversion is in a way misleading as actually nothing is converted:

the original word continues its existence alongside the new 1. The term

conversion refers to the numerous cases of phonetic identity of wordforms, primarily the so-called initial forms, of two words belonging to

different parts of speech. This may be illustrated by the following

cases: work — to work; love — to love; paper — to paper; brief — to

brief, etc. As a rule we deal with simple words, although there are a

few exceptions, e.g. wireless — to wireless.

Functional change (syntactic approach) implies that the process in

question concerns usage, not word-formation. Accepting the term

functional change 1 must admit that 1 & the same word can belong 2

several parts of speech simultaneously, which contradicts the basic

definition of a word as a system of forms

Conversion as morphological way of word formation (Smirnitsky): c.

is defined as a non-affixal, & its characteristic feature is that a certain

stem is used 4 the formation of a categorically different word without a

derivational affix being added. Conversion is widespread in E due 2

the absence of morphological elements serving as formal signs

marking the part of speech 2 which the word belongs.

27) Love – to love, to run - a run: A way of derivation or a

functional shift?

Conversion is especially productive in the formation of verbs

(can – to can? Phone – to phone), but not all the verbs were

created this way. Some of’em arose as a result of disappearance

of inflexions in the course of historical development of E due 2

which 2 words of different parts of speech coincided in

pronunciation (love – to love (OE lufian). That’s why some

scientists distinguish between homonymous word-pairs which

appeared as a result of the loss of inflections & those formed by

conversion. Conversion is applied 2 the pairs which came into

existence after the inflections disappeared. Others discriminate

between conversion as a derivational means & as a type of

word-building relations between words in ME. Taking in

consideration this idea love – to love is also a case of

conversion or zero derivation (способ словообразования без

использования спец словообразовательных аффиксов).

31) Semantic relations in conversion pairs and their

propositional basis.

Semantic relations between conversion pairs: verbs,

converted from nouns (if the noun refers 2 some object of

reality, the converted verb may denote: 1) action characteristic

of the object (ape n – ape v – imitate in a foolish way), 2)

instrumental use of the object (whip – to whip – strike with a

whip), 3) acquisition or addition of the object (fish – to fish –

catch fish), 4) deprivation of the object (dust – to dust – remove

dust from smt); nouns, converted from verbs (the verb refers 2

an action, the noun may denote: 1) instance of the action (to

jump – jump – sudden spring from the ground), 2) agent of the

action (to help – help – smb who helps), 3) place of the action

(to walk – walk – a place 4 walking), 4) object or result of the

action (to find – find – smt found).

30) Derivative relations in conversion and criteria of their directionality.

Поскольку происходящие при конверсии словообразовательные процессы

не имеют каких-либо специальных морфологических показателей и

формирование возможно как глаголов от существительных, так и сущ от

глаг, установление направления отношений словообразовательной

производности при конверсии, кот. вследствие своего немаркированного

характера именуются семантической производностью, - далеко не

праздный вопрос. Решается он с помощью ряда критериев: 1) кр.

содержания (установление направления внутренней производности путем

выявления семантической зависимости одного слова от другого: глаг knife

описывается через сущ, в то время, как сущ knife для своего

семантического анализа не требует ссылки к глаг knife). Сем. зависимость

ощущается носителями языка интуитивно. 2) кр. сем.

противоположности, возникающей между лексич. знач. корневой

морфемы и лекс-грам знач. основы у производных слов и отсутствующей

у производящих. 3) словообразовательный критерий (основан на

взаимосвязи слов внутри словообразовательного гнезда и учете характера

производности деривативов первой ступени в словообразовательном

гнезде. Если большинство из них являются отыменными производными,

то сущ, соотносящееся по конверсии с глаг в данном гнезде, непроизводно

(awe – простое слово, а глаг awe – производное, что подсказывается

отыменным характером др. производных aweless, awful). 4) кр. типовых

сем. отношений по конверсии (маркирующий признак деривата – его

значение. Производные по конверсии сущ и глаг развивают опред. типы

значений: отыменные глаг – такие знач., как действовать с пом. того, что

обозначается исх. сущ, помещать в место, кот. обозначено исх. сущ,

лишать того, что им обознач; отглаг сущ – единичное действие, место

действия, объект/результат действия. 5) кр. ограниченного употребления

(слово, не столь употребительное, как соотносящаяся с ним единица

другой части речи, явл. производным: глаг author – более ограниченная

сфера употребл., чем сущ author, и, следовательно, образован от него). 6)

наличие стилистических примет (to anger от anger).

29. zero derivation: adjec-tion, substan-tion, occasional conversion, root formation.

Zero-derivation – the way of word building without use of special derivational affixes;

Substantivation is a gradual process: adjs are first only partially substantivized and for a

long time can be modified by an adverb like regular adjs but not Ns (the extravagantly

jealous man). In contrast to conversion substantivation is limited to a certain class of

words: human beings (the poor, the black, a creative, a criminal) and some abstract

concepts (the impossible, the Present).

Adjectivization – the use of nouns and participles as adjs. E nouns are commonly used

in an attributive fun-n (a stone wall) but not all of them are adjs yet. The nominal character

of many premodifiers is proved by their correspondence to prepositional phrases with the

noun as the compliment (a love poem “a poem about love”) that can hardly be possible

for real attributive adjs like a long poem. Many adjs have the same form as participles

(surprising, offended), though only some of participles may be considered as converted

into adjs (*reading, *departed). The impossibility of using the intensifier “very” with these

words (very surprising but not *very departed) indicates that they are not adjs.

Occasional conversion. Traditional conversion refers to the accepted use of words

which are recorded in dictionaries, e.g. to age, to cook, to love, to look, to capture, etc.

The occasional use of conversion is also very frequent; verbs and adjs are converted

from nouns or vice versa for the sake of bringing out the meaning more vividly in a given

context only. In modE usage we find a great number of cases of occasional conversion,

e.g. How am I to preserve the respect of fellow-travellers, if I'm to be Billied at every turn?

Root-formation is when a certain stem is used for the formation of a different word of a

different part of speech without a derivational affix being added: Sound-interchange in E is

often combined with a difference in the paradigm. 3 types of relations should be distinguished:

1)breath—to breathe: sound-interchange distinguishes only between words, it does not

differentiate word-forms of one and the same word. It has no relation to the paradigms of the

words. 2)song—to sing: the vowel in song interchanges with 3 diff vowels, the latter

interchanging with one another in the forms of the verb to sing: song differs from to sing

(sang, sung) not only in the paradigm. Its root-vowel does not occur in the word-forms of the

verb and vice versa. 3)house—to house: sound-interchange distinguishing the 2 words (v & n)

is the same as that which distinguishes the word-forms of the noun, house [haus] —

houses [hauziz] and to house [hauz] — houses [hauziz].

34. Motivation and variability of word combinations.

Wordgroups may be described through the order and arrangement of the component

members. All word-groups may be analysed by criterion of distribution into 2 big classes.

In endocentric word-groups the central component that has the same distribution as the

whole group is clearly the dominant member or the head to which all other members of

the group are subordinated. In the word-group red flower the head is the N flower. It

follows that word-groups may be classified acc to their headwords into nominal groups

or phrases (red flower), adjectival groups (kind to people), verbal groups (to speak well).

The head is not necessarily the component that occurs first in the word-group.

Word-groups are also classified acc to their syntactic pattern into predicative and nonpredicative groups. Non-predicative word-groups may be subdivided acc to the type of

syntactic relations between the components into subordinative and coordinative.

Such word-groups as red flower, a man of wisdom are subordinative because the words

red and of wisdom are subordinated to flower and man respectively and function as their

attributes. Such phrases as women and children, day and night, do or die are

coordinative.___Word-groups like words may also be analysed from the point of view of

their motivation. Word-groups may be described as lexically motivated if the combined

lexical meaning of the groups is deducible from the meaning of their components. The

nominal groups, red flower, heavy weight and the verbal group, take lessons, are from

this point of view motivated, whereas structurally identical word-groups red tape, heavy

father, and take place are lexically non-motivated. Word-groups are structurally motivated

if the meaning of the pattern is deducible from the order and arrangement of the

member-words of the group. Red flower, is motivated as the meaning of the pattern

quality — substance can be deduced from the order and arrangement of the words red

and flower, whereas the seemingly identical pattern red tape cannot be interpreted as

quality — substance.____The degree of motivation may be different. For ex, the degree

of lexical motivation in the nominal group black market is higher than in black death, “but

lower than in black dress, though none of the groups can be considered as completely

non-motivated. It should also be noted that seemingly identical word-groups are

sometimes found to be motivated or non-motivated depending on their semantic

interpretation. Thus apple sauce, is lexically and structurally motivated when it means ‘a

sauce made of apples’ but when used to denote ‘nonsense’ it is clearly non-motivated. In

such cases we may even speak of homonymy of word-groups and not of polysemy.

33) Factors of government and binding words into phrases. Lexical and

grammatical valency.

Words R used in certain lexical contexts. The aptness of a word 2 appear in

various combinations is described as its lexical valency. The range of the LV

of words is linguistically delimited by inner structure of the E word-stock,

which can B easily observed in the choice of synonyms found in different

word-groups (lift & raise – raise a question, not lift). There’s a certain norm

of LV of each word & any departure from this norm is felt as stylistic device.

Words habitually collocated in speech tend 2 constitute cliché (the verb put

forward & the noun question R habitually collocated, they constitute a

habitual word-group). The LV of correlated words in different langs is not

identical (thin hair – жидкий волос). The LV & polysemy of word-groups R

interrelated: 1) the restrictions of LV of words may B manifested in the

choice of the lexical meanings of the polysemantic members of word-groups

(heavy may B combined with the words food, meals in the meaning difficult 2

digest), 2) different meanings of a word may B described through the LV of

the word (different meanings of the word heavy may B described thru the

word-groups heavy weight, heavy snow, heavy drinker.

Words R also used in gram. contexts. The minimal gram context in which the

words R used when brought together 2 form word-groups – the pattern of the

word-group. The aptness 2 appear in specific gram structures – grammatical

valency. It may B different. Its range is delimited by the part of speech the

word belongs 2 (adj can B followed by a noun, by the infinitive of a verb, etc

but not by the finite form of a verb), by the inner structure of the lang

(suggest & propose – both can B followed by a noun, only propose can B

followed by the infinitive of a verb (to propose 2 do smt), by comparing the

GV of correlated words in different langs (influence (v) can B combined only

with a noun, whereas Russian влиять – only with a prepositional group:

влиять на к-л). Any departure from the norm would make the word-group

unintelligible 2 English speakers. Individual meanings of a polysemantic

word may also B described thru its GV (keen – keen sight (keen + n), keen

on (keen + on + n), keen to know (keen + v).

32. A compound word - a free word combination - a

phraseological unit. Problems of boundaries and criteria.

Compounding or word-composition is one of the productive

types of word-formation in Modern English. Composition like

all other ways of deriving words has its own peculiarities as to

the means used, the nature of bases and their distribution, as to

the range of application, the scope of semantic classes and the

factors conducive to productivity.

Compounds, as has been mentioned elsewhere, are made up of

two ICs which are both derivational bases. Compound words

are inseparable vocabulary units. They are formally and

semantically dependent on the constituent bases and the

semantic relations between them which mirror the relations

between the motivating units. The ICs of compound words

represent bases of all three structural types. 1 The bases built on

stems may be of different degree of complexity as, e.g., weekend, office-management, postage-stamp, aircraft-carrier,

fancy-dress-maker, etc. However, this complexity of structure

of bases is not typical of the bulk of Modern English

compounds.

10) The behaviouristic and cognitive approaches to meaning.

In the behavioral semantics proposed by Bloomfield the

meaning of a linguistic form was defined as the situation in

which the speaker utters it and the response which it calls forth

in the hearer. Bloomfield's theory of meaning was affected by

his assumptions: his insistence on studying La in the manner of

the natural sciences, beginning with formal features such as the

phoneme and realizing a La as a reified object; his disavowal of

linguistic performance and individual variation as a significant

aspect in La science; his insistence that linguists be completely

objective in their approach, withholding their intuitions in

studying La "without prepossessions"; and his assumption that a

successful analysis is even possible through purely objective

observation. This approach doesn’t give any more or less

satisfying definition of meanin’. The diversity of linguistic

forms arising outta one & the same situation and serving as a

verbal stimulus directed at the listener & the diversity of

responses make the theory very vulnerable. Quite another view

on meaning is advocated by the prototype theory as a branch of

cognitive semantics (Rosch (1973). Here, meanings are

identified, often pictorially, by characteristic instances of

whatever class of objects, etc. a word denotes: Thus, a

prototypical instance of a bird would be a sparrow rather than a

penguin. In this sense, the denotation of a word is equated with

its prototype. Consequently, in contrast to truth-conditional

approaches, an essential claim of prototype theories is that

denotations have no precise limits.

13) Sem ambiguity. Polysemy versus homonymy. Criteria and ling frequency.

Ambiguity arises when a single word or string of words is associated with more than

1 meaning. 2 diff-t types of ambiguity can B distinguished on the basis of what is

causing it: lex ambiguity (arises when a word has multiple meanings) and structural

ambiguity (2 or more different syntactic structures can B assigned 2 1 string of

words. The expression «old men and women» is structurally ambiguous ‘coz it has

the following 2 structural analyses: old [men and women] - [old men] and women).

Ambiguous expressions that R not structurally ambiguous display lexical ambiguity.

The word «polysemy» means «plurality of meanings» it exists only in the La, not in

speech. A word with more than 1 meaning is called polysemantic. Different meanings

of a polysemantic word may come together due to the proximity of notions which they

express. E.g. the word «blanket» has the following meanings: a woolen covering

used on beds, a covering for keeping a horse warm, a covering of any kind /a blanket

of snow/, covering all or most cases /used attributively/, e.g. we can say «a blanket

insurance policy». Homonyms R words different in meaning but identical in sound or

spelling, or both.1 of the most debatable problems in semasiology is the borderline

between P. & H. (between different meanings of 1 word & the meanings of 2

homonymous words). If H. is viewed diachronically then all cased of sound

convergence of 2 or mo’ words may B regarded as H. Synchronically the

differentiation is based on the semantic criterion: if a connection between various

meanings is apprehended, these R 2 B considered as making up the semantic

structure of a polysemantic word, otherwise it’s H., not P. But this criterion isn’t

reliable as various meanings of the same word & the meanings of 2 or mo’ words

may B comprehended as synchronically unrelated; some of the meanings of lexicogrammatical h. arising from conversion R related (paper (n) – paper (v), so this

criterion can’t B applied 2 a large group of homonyms. ‘times different meanings of 1

word have stable relationships which R not found between the meanings of 2 h. It

can B seen in metaphoric meanings of one word (loud voice – loud colors). These

semant. relationships R indicative of P. When homonymic words belong 2 different

parts of speech they differ not only in their semantic structure but also in their

syntactic function & distribution (paper (n, can B preceded by the article & followed

by a verb) – paper (v, is never found in such distribution). In lexical homonymy there

R cases when none of the criteria can B applied.

16) Morphology as the study of language forms. Inflexional vs.

Derivational Morphology.

Morphology – the study of morphemes of a La of the way in which they

R joined 2 make words. An understanding of word-formation is necessary

for the study of La change, grammar. Words consist of 1 or more

morphemes. The basic definition of a morpheme is 'the smallest

meaningful unit of La'. Many words consist of just 1 morpheme (cat,

mouse, cattle). They can’t B broken down into any smaller units of

meaning. Words like catty, catfish, moused, cows on the other hand can B

broken down into smaller units of meaning: cat + -ty, where cat refers 2

the animal & -ty 2 the property of being like the animal. A word might

easily consist of 1 syllable & 2 morphemes (eats) or 2 syllables & 1

morpheme (cattle).

Free morphemes can stand alone. Bound morphemes can only occur when

joined on 2 another bound morpheme or 2 a free morpheme. Cat is a free

morpheme because it occurs alone in a sentence: Please feed my cat. -ty is

a bound morpheme because it can only occur when joined on to a free

morpheme like cat. It is traditional 2 distinguish inflexions from

derivations. Inflexions R the different forms of verbs & nouns used 2 mark

grammatical meanings such as tense, number and case. (He reads a book,

the verb read is inflected by adding a morpheme to show third person

singular. This morpheme is realised in speech by the sound /z/, & shown

in writing by -s). Derivations R new words which R formed by adding

meaning through affixes 2 other words. This usually has the effect of

changing the word class. (the verb read can have the suffix -able added 2

form the adjective readable, which in turn can have the prefix un- added 2

form another adjective unreadable, which, possibly, could have the suffix

-ness added 2 form the noun unreadableness). Such additions R known as

derivational morphemes, either prefixes or suffixes.

Both inflexional & derivational morphemes R bound. Free morphemes

can’t B inflexional or derivational. Where a word is formed by adding 1

free morpheme 2 another: catfish, the process is known as compounding

14) Homonymy. Types of homonyms.

Homonyms R words different in meaning but identical in sound or spelling, or both.

Classifications. Walter Skeat classified h. acc. to their spelling and sound forms three groups: perfect h. (identical in sound and spelling: «school» - «косяк рыбы» &

«школа»); homographs (words with the same spelling but pronounced differently:

«bow» -/bau/ - «поклон» and /bou/ - «лук»); homophones (pronounced identically

but spelled differently: «night» - «ночь» and «knight» - «рыцарь»).

Smirnitsky added 2 Skeat’s clas-n 1 mo’ criterion: grammatical meaning. Subdivided

the group of perfect h. into 2 types: perfect (identical in their spelling, pronunciation

and grammar form: «spring» - the season of the year, a leap, a source), &

homoforms (coincide in their spelling & pronunciation but have different grammatical

meaning: «reading» - Present Participle, Gerund, Verbal noun, to lobby – lobby).

A more detailed classi-n – Arnold: classified only perfect h. & suggested 4 criteria of

their classification: lexical meaning, grammatical meaning, basic forms and

paradigms. The following groups: a) homonyms identical in their grammatical

meanings, basic forms & paradigms & different in their lexical meanings («board» in

the meanings «a council» and « a piece of wood sawn thin»); b) homonyms identical

in their gram meanings & basic forms, different in their lexical meanings & paradigms

(to lie - lied - lied, & to lie - lay – lain); c) homonyms different in their lexical

meanings, grammatical meanings, paradigms, but coinciding in their basic forms

(«light» / «lights»/, «light» / «lighter», «lightest»/); d) homonyms different in their

lexical meanings, grammatical meanings, in their basic forms and paradigms, but

coinciding in one of the forms of their paradigms («a bit» and «bit» (from « to bite»).

In her classification there R also patterned homonyms (have a common component

in their lexical meanings). They are h. formed either by means of conversion, or by

levelling of grammar inflexions. They R different in their grammar meanings, in their

paradigms, identical in their basic forms («warm» - «to warm»). Here we can also

have unchangeable patterned homonyms which have identical basic forms, different

grammatical meanings, a common component in their lexical meanings («before» an

adverb, a conjunction, a preposition). There R also homonyms among unchangeable

words which R different in their lexical and grammatical meanings, identical in their

basic foms, e.g. « for» - «для» and «for» - «ибо».

17) The speaker – hearer approach to the analysis of the word structure:

morphemics vs. word formation.

With the help of ready verbal form the speaker names the object, & the hearer who

possesses the same language code easile decodes the information. Morphemic

analysis is limited 2 stating the number & type of morphemes making up the word

(girl(root morpheme + 1 or mo’ affixes) – ish – ness). A word formation analysis

studies the structural correlation with other words, the structural patterns or rules on

which words R built. This is done by means of the principle of opposition, by studying

the partly similar elements, the differences between which R functionally relevant.

Girl & girlish – members of morphemic opposition (similar as the root morpheme is

the same, the distinctive feature is the suffix –ish). This binary opposition comprises 2

elements. A correlation is a set of binary oppositions. It’s composed of 2 subsets

formed by the 1st & the 2nd elements of the opposition. Each element of the 1st set is

coupled with exactly 1 element of the 2nd set & vice versa. Each 2nd element may B

derived from the corresponding 1st element by a general rule valid 4 all members of

the relation. Child/childish = woman/womanish – observing this opposition we may

conclude that there’s in English a type of derived adj consisting of a noun stem & the

suffix –ish. Any word built acc. 2 this pattern contains a semantic component

common 2 the whole group (typical of, having bad qualities of). But there R cases

when the results of morphemic analysis & the structural word-formation analysis do

not coincide. The morphemic analysis is insufficient in showing difference between

the structure of inconvenience v & impatience n, classifying both as derivatives. From

the point of view of the 2nd approach they R different: inconvenience is a derivative

(impatience/impatient = patience/patient), inconvenience (v)/inconvenience (n) here

we deal with conversion. This approach also affords a possibility 2 distinguish

between compound words formed by composition & those formed by other

processes. Honeymoon (n) & honeymoon (v) R both compounds with 2 free stems,

but the 1st is formed by composition (honey + moon = honeymoon (n), the 2 nd – by

conversion (honeymoon (n) – honeymoon (v). Here it’s not the origin of the word is

established but its present correlations in the vocab & the patterns productive in the

present-day English.

12) Semantic derivation. Causes, types and functions.

Derivation - a major process of word formation, especially using affixes to produce new

words. Causes: 1) extralinguistic (various changes in the life of speech community,

changes of economic & social structure, changes of ideas, scientific concepts, way of life &

other spheres of human activities as reflected in word-meanings; Historical, Psychological

(taboo, euphemism (words (with neutral or positive) connotation, 2 veil painful concepts) problematic concepts avoided in speech, e.g. Death, disease, excretion, sex, neutral

designations for minorities (cripple, handicapped, black, coloured, African-American); 2)

linguistic (the commonest form which this influence takes is the so-called ellipsis (when in a

phrase made up of 2 words one of these is omitted & its meaning is transferred 2 its partner

(the Kremlin = советск пра-во (the Kremlin government), meaning of 1 word is transferred 2

another ‘coz they usually occur in speech together (daily = daily newspaper); discrimination

of synonyms (can B illustrated by the semantic development of a number of words: land in

OE meant both solid part of earth’s surface & the territory of a nation, in ME the word country

was borrowed as its synonym the meaning of land altered & the territory of a country came 2

B denoted by country); semantic analogy (if 1 of the membas of a synonymic group acquires

a new meaning other membas change their meaning too(verbs synonymous with catch

(grasp, get) acquired meaning “to understand”).

Types: generalization (shifting of a word from a more specific meaning to a more general

one: arrive (Fr rive = 'bank of a river, shore') - originally: 'arrive on shore, come to shore' then

'arrive, come to an undefined place'), specialization (narrowing; occurs when a word

originally referred to a broad category, but over time narrows in scope to refer only to a once

was what a subcategory: liquor originally meant any liquid), elevation (amelioration; the

connotation of a word may shift toward the positive: terrible), & pejoration (degradation; the

connotation of a word may shift toward the negative: silly meant happy, blessed), metaphor

(an implicit comparison is made by using a word with one meaning to stand for something

with a similar or analogous meaning. A word for something concrete and familiar is

metaphorically extended to refer to something abstract or less familiar: bright, brilliant – as

applied to intellect, the mouth of a river or a bottle, the eye of a needle or a hurricane, the

foot of a hill), metonymy (a similar substitution is made, but on the basis of contiguity rather

than similarity —a word with one meaning is used to stand for something connected or

related to that meaning: cash (Fr casse) originally a box or chest for keeping money; now the

money itself; the names of the organs of sense are often used metonymically to refer to the

senses, or to the exercise of them: an ear for music, catch someone’s eye).

Functions: makes lexicon consistent & continuous, it’s an efficient source for novel

meanings & leads 2 polysemy.

15) Patterned polysemy of lexical units in English.

Several types of polysemy occur so frequently that they should B

considered part of the grammatical knowledge of the speakers of a La.

First, we have count/mass alternations for nouns, which can serve

several functions: Animal/meat (The lamb is running in the field. John ate lamb for breakfast), Object/Stuff an object is made up (There

is an apple on the table. - There is apple in the salad), Stuff/Kind (

There was cheese on the table. - Three cheeses were served),

Stuff/Portions (The restaurant served beer, and so we ordered three

beers), Plant/food alternation (Mary watered the fig in the garden. Mary ate the fig), We have alternations between containers and

contained (Mary broke the bottle. - The baby finished the bottle),

Figure/Ground reversal (The window is rotting. - Mary crawled

through the window), Product/producer alternation (newspaper,

Honda: The newspaper fired its editor. - John spilled coffee on the

newspaper), Process/result alternation (The company’s merger with

Honda will begin next fall. - The merger will lead to the production of

more cars), Alternations involving location: Building/institution (

university, bank), Place/people (John traveled to New York. - New

York kicked the mayor out of office), Capital/government

(Washington accused Havana not to do enough for the victims).

Each polysemic word has its central meaning which is usually

understood without the context. All the other meanings R secondary &

we need context 2 understand them (yellow – color, yellow look

(envy). The context individualises the meaning & brings it out (lexical

c (the lexical meaning of the words of the context which surround the

given word) & gram c (the meaning of the word make as force is

possible only in the gr combination to make smb do smth. In another

combination it’ll have allegoric meaning (to become, to make a good

teacher)

18) The morpheme as the smallest meaningful unit.

Principles and methods of morphemic analysis.

Morpheme is the minimum meaningful La unit; it’s an

association of a meaning with a sound form but unlike words

morphemes R not independent & occur in speech only as

constituent parts of words; they can’t B divided into smaller

meaningful units. In most cases the morphemic structure of

words is transparent enough & individual morphemes clearly

stand out within’ the word. The segmentation of words is

carried out acc. 2 the method of Immediate & Ultimate

Constituents based on the binary principle – each stage of the

procedure involves 2 components the word immediately breaks

into. At each stage the constituents R broken into smaller

meaningful elements until further division is impossible. At this

point we deal with morphemes referred 2 as Ultimate

Constituents. (friendliness – friendly + ness (-ness can’t B

further divided =› it’s a morpheme), friend + ly). Morphemic

analysis under the method of Ucs may B carried out on the

basis of 2 principles: root principle (the segmentation of the

word is based on the identification of the root-morpheme in a

word-cluster: identification of the root-morpheme agree- in

agreeable, agreement), affix principle (based on the

identification of the affix within a set of words: the suffix –er

leads 2 the segmentation of words singer, teacher into the

derivational morpheme –er & the roots sing-, teach-)

37) Linguistic laws of phraseological units’ formation. Activity of

words and syntactic patterns.

According 2 the way PU R formed Koonin pointed out: primary ways (a

unit is formed on the basis of a free word-group): by means of transferring

the meaning of terminological word-groups (in cosmic technique we can

point out the following phrase to link up - cтыковаться, стыковать

космические корабли in its transformed meaning it means –

знакомиться); by transforming the meaning of free word groups (granny

farm - пансионат для престарелых), alliteration (a sad sack несчастный случай), by means of expressiveness, characteristic 4

forming interjections (My aunt!, Hear, hear !), by distorting a word group

(odds and ends from odd ends), by using archaisms (in brown study

means in gloomy meditation where both components preserve their

archaic meanings), by using a sentence in a different sphere of life (that

cock won’t fight can B used as a free word-group when it is used in sports

(cock fighting), it becomes a PU when it is used in everyday life, ‘coz it is

used metaphorically), when we use some unreal image (to have butterflies

in the stomach - испытывать волнение), by using expressions of writers

or politicians in everyday life (the winds of change (Mc Millan).

Secondary ways - PU is formed on the basis of another phraseological

unit: conversion (to vote with one’s feet was converted into vote with

one’s feet); changing the grammar form (Make hay while the sun shines is

transferred into a verbal phrase to make hay while the sun shines);

analogy (Curiosity killed the cat was transferred into Care killed the cat);

contrast (thin cat - «a poor person» was formed by contrasting it with «fat

cat»); shortening of proverbs or sayings (from the proverb «You can’t

make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear» by means of clipping the middle of it

the PU «to make a sow’s ear» was formed with the meaning

«ошибаться»); borrowing either as translation loans (living space

(German), to take the bull by the horns ( Latin) or by means of phonetic

borrowings (meche blanche (French), corpse d’elite (French).

40) Main types of English dictionaries.

English dict. may B divided into 2 types: encyclopaedic

(Britannica, Americana) & linguistic (word-book, thing-book).

Acc. 2 the nature of the word-list: general (lin. units in ordinary

use), restricted (terminological, phraseological, dialectical).

Acc 2 the lang. on which information is given: bilingual,

monolingual. Acc. 2 the kind of information: explanatory,

translational. Each dict. has a certain aim. Criteria: nature of

the word list, information supplied, La of explanation,

prospective user. Specialized: phraseological, new words dict,

of slang, usage dict, of word frequency, pronouncing,

etymological, ideographic

43) Stylistic classification of the English vocabulary.

We speak differently in diff. situations. The way we speak and

the choice of words depend on the situation in which the

process of communication is realized. As we are speaking about

the functions of all this words in diff. situations we have to

define “functional style”.Functional style may B defined as a

system of expressive means peculiar 2 a specific sphere of

communication. The broadest division of E lexis is: formal

(varieties of E vocab that occur in books, magazines, we hear

from public speaker, radio, TV, formal talk. Words R used with

precision, generalized. Written speech, special technology,

poetic diction, official vocab & learned words (archaic –

thereby, hereby, thereupon, moreover, as follows), officialese,

journalese (clichés: dispatch, donation, sustain, conveyance) &

informal (used in every day speech; literary (colloquial (vocab

used by educated ppl in ordinary conversation), old generation

of writers, familiar colloquial – young generation of writers,

low colloquial – illiterate popular speech (blurred bound

between dialect), argot (special vocab & idioms used by a

community within the society (social/age group, criminal

circles), slang (ironical expressions, which serve 2 create fresh

names 4 some things that R frequent topics of discussion. 2

types of slang: general (words not specific 4 any social, age,

prof. Group) & special (teenage, university, military, football

slangs)

36) Types of phraseological units. Classifications and their evaluation.

1) the degree of motivation of their meaning (Vinogradov): fusions (very low, we can’t guess

the meaning of the whole from the meanings of its components; highly idiomatic & cannot

B translated word 4 word: at sixes and sevens (in a mess); unities (the meaning of the whole

can B guessed from the meanings of its components, but it is metaphorical or metonymical:

old salt (experienced sailor); collocations (words R combined in their original meaning but

their combinations R diff in diff Las: cash and carry (self-service shop).

2) Structural classification (Smirnitsky). Points out one-top units (compared with derived

words ‘cause d. w’s have only 1 root morpheme), & two-top units (compared with

compound words ‘coz c. w’s R usually of 2 root morphemes).

ONE-TOP UNITS: verb + postposition type (to give up, to drop out); units of the type «to

be tired» (they can remind the Pas Voice in their structure (but they have diff preps with

them, while in the Pas Voice we can have only prepositions «by» or «with»), free wordgroups of the type «to be young» (to be aware of, but the adj «young» can B used as an

attribute & as a predicative in a sentence, while the nominal component in such units can

act only as a predicative). In these units the V is the grammar centre and the 2nd

component is the semantic center); prepositional-nominal (equivalents of preps, conjs,

advs, that is why they have no grammar centre, their semantic centre is the nominal part

(on the doorstep (quite near), in the course of, in time). TWO-TOP UNITS: attributivenominal (a month of Sundays, grey matter; noun equivalents & can B partly or perfectly

idiomatic. In partly idiomatic units the 1st component is idiomatic (high road), in other

cases the 2nd component is idiomatic (first night); verb-nominal (to read between the

lines, - the grammar centre of such units is the verb, the semantic centre - the nominal

component. In some units the verb is both the grammar & the semantic center (not to

know the ropes); phraseological repetitions (now or never, - can B built on antonyms (ups

and downs, back and forth). Components in R joined by means of conjunctions.

equivalents of adverbs or adjectives & have no grammar centre. They can also B partly

or perfectly idiomatic (cool as a cucumber (partly), bread and butter (perfectly).

3) Arnold classified’em as parts of speech: N phraseologisms (denote an object, a

person, a living being: bullet train, latchkey child, Green Berets), V (denote an action, a

state, a feeling: to break the log-jam, to nose out), adjective (a quality: loose as a goose,

dull as lead), adverb (with a bump, like a dream), preposition (in the course of, on the

stroke of), interjection («Catch me!», «Well, I never!»).

39) Lexicography. History of British and American lexicography .

Lexicography - the theory & practice of compiling dictionaries. The history of compiling

dictionaries for E comes as far back as the OE period (glosses of religious books interlinear translations from Lat into E). Regular bilingual dictionaries began 2 appear in

the 15th c. (Anglo-Lat, Anglo-Fr, Anglo-German).

1604 Robert Cawdry - the 1st unilingual dictionary compiled 4 schoolchildren. 1721,

Nathan Bailey - the 1st etymological dictionary which explained the origin of English

words (compiled 4 philologists). 1775, Samuel Johnson – an explanatory dictionary

(influenced the development of lexicography in all countries). Words were illustrated by

examples from E literature, the meanings were clear from the contexts in which they were

used. It influenced normalization of the E voc, helped 2 preserve the E spelling in its

conservative form. 1858 the question of compiling a dictionary including all the words

existing in the L was raised. Mo’ than a thousand people took part in collecting examples,

& 26 yrs later in 1884 the 1st volume was published (contained words beginning with «A»

& «B»). The last volume was published 70 yrs after the decision 2 compile it was adopted.

The dictionary was called NED and contained 12 volumes. In 1933 the dictionary was

republished under the title «The Oxford E Dictionary», ‘coz the work on the dictionary was

conducted in Oxford. 13 volumes. As the dictionary was very large and terribly expensive

shorter editions were compiled: «A Shorter Oxford Dictionary» (2 volumes, the same

number of entries, but far less examples). «A Concise Oxford Dictionary» was compiled

(1 volume, only modern words, no examples from lit-re).

The American L began 2 develop at the end of the 18th c. The most famous American

English dictionary was compiled by Noah Webster who published his 1st dictionary in

1806. He went on with his work on the dictionary and in 1828 he published a 2-volume

dictionary. Tried 2 simplify the English spelling & transcription, introduced the alphabetical

system of transcription where he used letters & combinations of letters instead of

transcription signs, denoted vowels in closed syllables by the corresponding vowels, (/a/,

/e/, /i/, /o/, /u/). He denoted vowels in the open syllable by the same letters, but with a

dash above them (/a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, /u/). He denoted vowels in the position before /r/ as the

same letters with two dots above them & by the letter «e» with two dots above it for the

combinations «er», «ir», «ur» because they R pronounced identically. The same

tendency is preserved 4 other sounds: /u:/ is denoted by /oo/, /y/ is used 4 the sound /j/.

42. Etymological survey of the English vocabulary.

The term “etymology” comes from Greek and it means the study of the earliest forms of

the word. Now etymology studies both: the form and the meaning of borrowed and native

words. In every modern La there are native and borrowed words. As for E L many

scientist consider the foreign influence to be the most important factor in the development

of the E L. There are more borrowed words in E than in any other European L. It contains

the native element and the borrowed elements. The native element includes IndoEuropean, Germanic element and E proper element. boy, girl, lord, lady – proper E word.

By the Indo-European element are meant words of roots common to all Ls of the IndoEuropean group. The words of this group denote elementary concepts without which no

human communication would be possible. The following groups can be identified: 1.

Family relations: father, mother, brother, son, daughter; 2. Parts of the human body: foot,

nose, lip, heart; 3. Animals: cow, swine, goose; 4. Plants: tree, birch, corn; 5. Time of day:

day, night; 6. Heavenly bodies: sun, Numerous adjectives: red, new, glad, sad; 7. The

numerals from one to a hundred; 8. Pronouns - personal (except “they” which is

aScandinavian borrowing) and demonstrative; 9. Numerous verbs: be, stand.

The Germanic element represents words of roots common to all or most Germanic Ls.

Some of the main groups of Germanic words are the same as in the Indo-European

element: 1. Parts of the human body: head, hand, arm, finger, bone; 2. Animals: bear,

fox; 3. Plants: oak, fir, grass; 4. Natural phenomena: rain, 5. Seasons of the year: winter,

6. Landscape features: sea, 7. Human dwellings and furniture: house, room, bench; 8.

Sea-going vessels: boat; 9. Adjectives: green, blue, grey, white, small, thick, high, 10.

Verbs: see, hear, speak, tell, say, answer, make, give.

The E proper element is opposed to the 1st two groups. For not only it can be

approximately dated, but these words have another distinctive feature: they are

specifically E have no cognates in other Ls whereas for Indo-European and Germanic

words such cognates can always be found, as, for instance, for the following words of the

Indo-European group. Star: Germ. - Stern, Lat. - Stella, Gr. - aster. Stand: Germ. –

stehen, Lat. - stare, R. – стоять.

Here are some examples of English proper words: bird, boy, girl, lord, lady, woman,

daisy, always. Latin affixes of nouns: The suffix (-ion): legion, opinion, etc.; the suffix (tion): relation, temptation, etc.

35) Free phrases versus phraseological units. Criteria and

difficulties of differentiation.

Free phrases vs set-phrases. The border line between free

phrases & set phrases is not clearly defined. The so-called free

phrases R but relatively free as collocability of member-words

is fundamentally delimited by their lexical & grammatical

valency which makes at least some of them very close 2 setphrases. Set-phrases R but comparatively stable & semantically

inseparable. The existence of different terms 4 1 & the same

phenomenon (set-phrases, idioms, word-equivalents) reflect the

main debatable issues of phraseology (different views

concerning the nature & essential features of phraseological

units as distinguished from free-phrases. The term set-phrase

implies that the basic criterion of differentiation is stability of

the lexical components & grammatical structure of wordgroups. The term idioms implies that the essential feature of the

linguistic units is idiomacity (lack of motivation). The term

word-equivalent stresses not only semantic but also functional

inseparability of certain word-groups, their aptness 2 function

in speech. Thus phraseological units R habitually defined as

non-motivated word-groups that can’t B freely made up in

speech but R reproduced as ready-made units, the essential

features of phraseological units being stability of the lexical

components & lack of motivation. Components of free-phrases

vary according 2 the needs of communication, components of

set-phrases R always reproduced as single unchangeable units.

38) Contrastive study of phraseology. Common sources as the

foundation for equivalent phraseological units. Socio-cultural

properties of phraseological units.

В большинстве своем фразеологизмы в англ – исконные. Во

многих из них отражаются традиции, обычаи и поверья англ

народа, различные реалии и факты англ истории (sit above the

salt). Важнейш источник исконных фразеологизмов – проф

речь: armed at all points («во всеоружии» - военн происхожд).

Многие исконные фр-мы – лит происхождения (1 место по

числу фр-мов, вошедших в англ, заним. произведения

Шекспира. Лит произведения, написанные на др яыках,

становятся важнейш источником заимствован фразеологизмов.

Среди них как наиболее значимые – Библия (метать бисер

перед свиньями – cast pearls B4 swine), античная мифология и

лит-ра (золотая середина – the golden mean (Гораций). Лит

произведения играют существ роль и для группы фр-мов,

заимствованных из амер варианта англ (последний из Могикан

– the last of Mohicans). Эквивалентность фр-мов в разных язах

зачастую явл. следствием общности их происхождения и,

наоборот, отсутствие эквивалентного фр-ма – специфики его

источника. Наиб. степень эквивалентности присуща фр-мам

заимствованным (Библия, античная мифология, греч. и римск.

лит-ра). Встречаются эквивалентные фр-мы и среди исконных

фр-мов, но их очень мало (смеется тот, кто смеется последним

– He laughs best who laughs last, куй железо, пока горячо – Strike

while the iron is hot). Среди исконных фр-мов превалируют те, у

кот. имеются лишь частично эквивалентные им фр-мы в др

языке или же вообще отсутствуют аналоги.

41) Problems of lexicographic description.

1) Selection of ling. units 4 inclusion. This process is necessary

4 compiling any dictionary. Which form (spoken/written),

number of items, what 2 select, what 2 leave out (technical

terms, dialectisms, colloquialisms, archaisms). Depend on type

of dictionary, aim, prospective user, size. 2) Arrangement of

entries (alphabetical (easy 2 use), cluster type order, frequency

(descending order; less space, clearer picture of relations of

each unit with other units). 3) Selection & arrangement of

meanings (some give meanings that R of current use, some –

obsolete ones (diachronic/ synchronic dict.) 3 ways meanings R

arranged: historical order (sequence of their historical

development), actual order (frequency of use), logical order

(logical connection). Sometimes the primary meaning comes 1st

if this is important 4 a correct understanding of derived

meanings. 4) Definition of meanings: encyclopaedic (determine

the concept, common of nouns & terms), descriptive (give word

meaning, used in majority of cases), synonyms & expressions

(common 4 verbs, adj), references (see defence, common 4

derivatives, abbreviations, variant forms) 5) Illustrative

examples. Diff. purposes illustrating changes in

graphic/phonetic form as well as meaning, typical patterns &

collocations, differences between synonyms, place words in

context 2 clarify meaning. Should B made up or quoted from

literature? How much space? Diachronical dicts – quotations

from literature (author, source, date should B noted),

synchronical dict (classical, contemporary sources, only

author).

19) Difficulties of segmentation and classification of morphemes.

Possible solutions.

1) Pseudo-morphemes - sound-clusters which have a differential & a

certain distributional meaning, but luck lexical meaning of their own

(retain, detain – receive, deceive, re- & de- have nothing in common

with the phonetically identical prefixes re- & de- (re-organize, deorganize), neither re- or de- nor –tain, -ceive posees any functional or

lexical meaning, yet they R felt as having a certain meaning because

re- distinguishes retain from detain.) 2) Unique root – bound

morphemes, not recurrent in other word groups & possessing only

differential & distributional meaning (pocket, islet can B confused

with such words as lionet, locket, which have a diminutive suffix–et.

But unlike root-morphemes lion, lock, recurring in other words, the

sound cluster [pok-] doesn’t & has no denotational meaning. Other ex.

word hamlet comparing with streamlet, leaflet or compound words

cranberry, gooseberry). 3) A special kind of bound root-morphemes

different from root-morphemes occurring in ordinary compounds.

(graph-, tele-, scope- R characterized by quite a definite lex. meaning

& peculiar stylistic reference. Analysis of such words as telegraph,

telephone & autograph, phonograph may lead 2 conclusion that they

contain no root-morpheme & R composed of a suffix & a prefix). 4)

Semi-affixes - root-morphemes functioning as derivational morphemes

(the morphemes half- & ill- in such words as ill-mannered, half-done

though they seem 2 retain the status of roots, have become at the same

time mo; indicative of a generalized meaning than of the individual

lexical meaning proper 2 the same morpheme in independent words;

they R losing their semantic identity with roots in independent words

& don’t function as their lexical centres; instead they modify the root

morpheme applying to it a general characteristic of incompleteness &

poor quality)

20. Morphemic types of English words and their role in the

lexicon and speech.

According to the number of morphemes words are classified

into monomorphic and polymorphic. Monomorphiс or rootwords consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. small, dog,

make, give, etc. All pоlуmоrphiс words according to the

number of root-morphemes are classified into two subgroups:

monoradical (or one-root words) and polyradical words, i.e.

words which consist of two or more roots. Monoradical words

fall into two subtypes: 1) radical-suffixal words, i.e. words that

consist of one root-morpheme and one or more suffixal

morphemes, e.g. acceptable, acceptability, blackish, etc.;