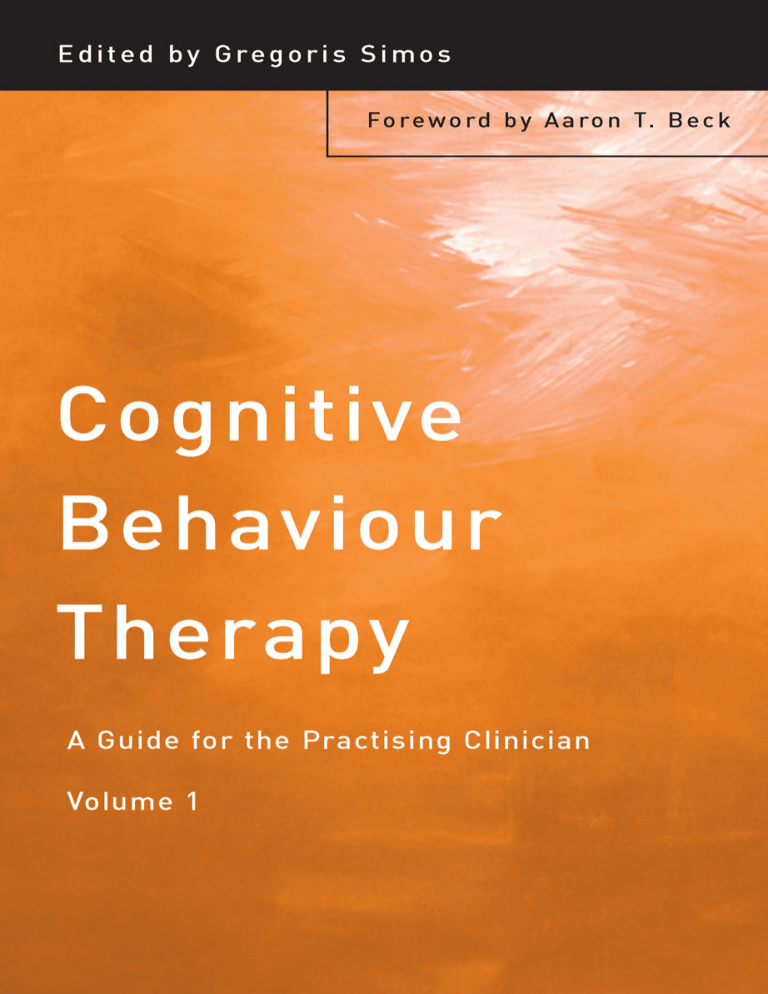

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) has a well-elaborated theoretical background and documented standard therapeutic process. However, new specific theoretical formulations and genuine techniques seem to continually appear. These new treatment developments in CBT constitute the heart of this book. Leading researchers and clinicians, who are also well-established experts in the application of CBT, present the extent of their experience, as well as appropriate and state-of-the-art treatment techniques for a variety of specific disorders. Topics covered in this book include: • • • • Management of major depression, suicidal behaviour and bipolar disorder Treatment of anxiety disorders, such as panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder and generalised anxiety disorder Application of CBT to eating disorders and personality disorders, especially borderline personality disorder Implementation of CBT with specific populations, for example couples and families or children and adolescents. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: A Guide for the Practising Clinician is a clinical practice oriented and treatment techniques focused book which allows for adequate flexibility in order to help the practising clinician become more competent and efficient in applying cognitive behaviour therapy. It will be invaluable to clinicians, researchers and mental health practitioners. Gregoris Simos, MD, PhD, is a cognitive behavioural clinician at the Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, Greece. He is on the United Kingdom Council of Psychotherapy and an accredited Cognitive and Behavioural Psychotherapist, and is a founding member and current President of the Greek Association for Cognitive and Behavioural Psychotherapies. He is also a Founding Fellow of the Academy of Cognitive Therapy, USA. This page intentionally left blank Cognitive Behaviour Therapy A Guide for the Practising Clinician Gregoris Simos First published 2002 by Brunner-Routledge This edition published 2012 by Routledge 27 Church Road, Hove, East Sussex BN3 2FA 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2002 Gregoris Simos selection and editorial matter; individual chapters, the contributors Typeset in Times by M Rules, London Cover design by Terry Foley All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. This publication has been produced with paper manufactured to strict environmental standards and with pulp derived from sustainable forests. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-1-58391-105-1 (pbk) ISBN 978-1-58391-104-4 (hbk) To all those who were – and as such, will always be – my teachers. This page intentionally left blank Contents List of figures and tables About the editor List of contributors Preface Introduction ix x xi xiii 1 AARON T. BECK 1 The cognitive treatment of depression Appendices 3 41 KEVIN T. KUEHLWEIN 2 Cognitive behavioural treatment of suicidal behaviour 49 ARTHUR FREEMAN AND JAMES JACKSON 3 Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder 71 CORY F. NEWMAN 4 Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 97 GREGORIS SIMOS 5 Psychosocial treatment for OCD: Combining cognitive and behavioural treatments 125 MAUREEN L. WHITTAL, S. RACHMAN, AND PETER D. MCLEAN 6 Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and generalised anxiety disorder MICHELLE G. NEWMAN AND THOMAS D. BORKOVEC 150 viii 7 Contents Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 173 DAVID M. GARNER AND M. TERESA BLANCH 8 Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders 201 JEFFREY E. YOUNG 9 Letting it go: Using cognitive therapy to treat borderline personality disorder 223 SUSAN B. MORSE 10 Techniques and strategies with couples and families 242 FRANK M. DATTILIO 11 Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 275 AUDE HENIN, MELISSA WARMAN, AND PHILIP C. KENDALL Index 315 Figures and tables Figures 4.1 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 10.1 10.2 The cognitive model of panic disorder Cognitive behavioural model of obsessive compulsive disorder Downward arrow of a man obsessed with accuracy The pie-chart technique Downward arrow of a compulsive cleaner/organiser Levels of cognition Channels of input in relation to age Thought record – Part 1 Adaptive responses: Thought record – Part 2 The downward arrow technique Reframing 99 132 135 138 141 226 230 238 239 246 265 Tables 5.1 5.2 7.1 7.2 7.3 8.1 9.1 9.2 Overview of CBT for OCD An example of a cumulative odds ratio for a compulsive checker Major content areas for cognitive therapy The effects of semi-starvation from the 1950 Minnesota study Steps in cognitive restructuring Schema domains Eriksonian stages associated with schema development Parallels between Piagetian and borderline characteristics 136 140 180 183 188 208 229 232 About the editor Gregoris Simos graduated from the Medical School of the Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, Greece, and was trained in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the 2nd Department of Psychiatry of the same University. Part of his post-graduate training was conducted at the Institute of Psychiatry, University of London, where he worked with Professor Isaac M. Marks (Psychological Treatment Unit), Professor Gerald Russell (Eating Disorders Clinic) and Dr Michael Crowe (Sexual and Marital Problems Clinic). Dr Simos also trained at the University of Pennsylvania (Center for Cognitive Therapy) under the direction of Aaron T. Beck, MD. He earned his PhD at the Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, Greece, where he is currently involved in research and teaching. Dr Simos is regarded as a leading cognitive behavioural clinician in Greece. He is also on the United Kingdom Council of Psychotherapy, an accredited Cognitive and Behavioural Psychotherapist, and is a founding member and current President of the Greek Association for Cognitive and Behavioural Psychotherapies. He is also a member of the Editorial Board of the Journal of Anxiety Disorders. Dr Simos is the editor of the series “Bibliotherapy”, published by Patakis Publishing Co., and under his supervision has already translated into Greek Helen Singer-Kaplan’s PE: How to Overcome Premature Ejaculation, David Burns’ Feeling Good, Aaron T. Beck’s Love is Never Enough, Janet Klosko and Jeffrey Young’s Reinventing Your Life, and Christopher Fairburn’s Overcoming Binge Eating, Frank Lamagnere’s Manies, Peurs et Idées Fixes, Alan Garner’s Conversationally Speaking, Robert Alberti and Michael Emmon’s Your Perfect Right!, and Judith Beck’s Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. He is also a Founding Fellow of the Academy of Cognitive Therapy, USA. Contributors M. Teresa Blanch, MA Altabix Mental Health Center, Alacant, Spain. Thomas D. Borkovec, PhD Department of Psychology, The Pennsylvania State University, 417 Bruce V. Moore Building, University Park, PA 168023104, USA. Frank M. Dattilio, PhD ABPP Center for Integrative Psychotherapy, Suite 211-D, 1251 S Cedar Crest Boulevard, Allentown, PA 18103, USA. Arthur Freeman Department of Psychology, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, 4190 City Avenue, Philadelphia, PA 19131-1693, USA. David M. Garner, PhD River Centre Clinic, 5465 Main Street, Sylvania, OH 43617, USA. Aude Henin, PhD Massachusetts General Hospital, Department of Psychiatry, 50 Staniford Street, Suite 580, Boston, MA 02114, USA. James Jackson Department of Psychology, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, 4190 City Avenue, Philadelphia, PA 19131-1693, USA. Philip C. Kendall, PhD, ABPP Temple University, Department of Psychology, Weiss Hall (265–66), Philadelphia, PA 19122, USA. Kevin T. Kuehlwein, PsyD University of Pennsylvania, Center for Cognitive Therapy, Room 754, The Science Center, 3600 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104-2648, USA. Peter D. McLean, PhD Department of Psychiatry, UBC Hospital, 2255 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, BC, V6T 2B5, Canada. Susan B. Morse, PhD Creative Cognitive Therapy Productions, 2118 Central, SE # 46, Albuquerque, NM 87106, USA. Cory F. Newman, PhD University of Pennsylvania, Center for Cognitive xii Contributors Therapy, Room 754, The Science Center, 3600 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104-2648, USA. Michelle G. Newman, PhD Department of Psychology, Penn State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA. S. Rachman, PhD Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z4, Canada. Gregoris Simos, MD, PhD Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, CMHC/2nd Department of Psychiatry, 15 Komninon Street, 546 24 Thessaloniki, Greece. Melissa Warman, PhD Temple University, Department of Psychology, Weiss Hall (265–66), Philadelphia, PA 19122, USA. Maureen L. Whittal, PhD Anxiety Disorders Unit, UBC Hospital, 2211 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, BC, V6T 2B5, Canada. Jeffrey E. Young, PhD Cognitive Therapy Center of New York, Suite 530, 120 East 56 Street, New York, NY 10022, USA. Preface Since its development in the 1960s, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) has already acquired its own solid and individual identity in the field of developmental and clinical psychology. Whereas in 1967 CBT originated through a rather experimental approach with Aaron T. Beck and colleagues’ efforts to articulate a comprehensive method of understanding and treating depression, it has become, along with psychodynamic and behaviour therapy, one of the three major psychotherapeutic modalities. Dr Beck is second only to Freud in the number of citations to his work in the psychiatric literature. Cognitive therapy of depression was nevertheless only the beginning – CBT has already proven its effectiveness with anxiety disorders including panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder and generalised anxiety disorder; CBT has also been found to be effective in the management of eating disorders, couples and family problems, personality disorders, substance abuse, bipolar disorder, along with a number of other disorders. New developments in the use of CBT include its implementation with children and adolescents, crisis intervention, schizophrenic patients, and inpatient treatment. A part of the “cognitive revolution” is reflected in the increasing number of articles, books, and book chapters on CBT in the literature. A search in the Excerpta Medica/Psychiatry database (EMBASE CD: Psychiatry, Elsevier Science BV) shows that during 1985–1995, 7891 articles were indexed under the general term “psychotherapy”, while 4674 articles were indexed under the terms “behavior therapy” and “cognitive therapy”. Therefore, why another handbook on CBT? There are several reasons; however, the most prominent one has to do with the integrative nature of CBT. CBT fulfils the criteria for a true system of psychotherapy by virtue of the fact that it provides a comprehensive theory of psychopathology and a body of knowledge and empirical evidence to demonstrate its effectiveness. It also retains a certain degree of flexibility in its philosophy and theory, allowing for the accommodation of other modalities. On the treatment implementation level CBT is continually evolving. Therefore, since no treatment modality has currently been found to be universally and totally effective, CBT is on the move toward both a self-refinement and self-integration that in xiv Preface an ever changing way will become even more powerful as a treatment option. This last aspect of CBT is also reflected in the fact that CBT is considered to be the most heavily researched form of psychotherapy. In a survey by Norcross and Prochaska (1988), which examined the most frequent combinations of theoretical orientations, the majority of clinicians favoured an integrative approach, with the highest percentage rating cognitive behaviour therapy as their number one choice. Although CBT has a well-elaborated theoretical background and documented standard therapeutic process, new specific theoretical formulations and genuine techniques seem to be continually appearing. These new treatment developments in CBT constitute the heart of this book. Leading researchers and clinicians, who are also well-established experts in the application of CBT, present the extent of their experience, as well as appropriate and state-of-the art treatment techniques for a variety of specific disorders. A final note of appreciation. I really feel indebted to all authors of this book for the great deal of work they have put into their chapters. Taking advantage of the saying “all people are equal, but some of them are more equal than others”, I would like to express additional appreciation to Frank Dattilio for his always willing, accurate, and valuable guidance throughout the process of editing this book. Gregoris Simos, MD, PhD Reference: Norcross, J.C. & Prochaska, J.O. (1988). A study of eclectic (and integrative) views revisited. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 19, 170–174. Introduction Aaron T. Beck I am delighted to write this introduction to Cognitive Behavior Therapy: A Guide for the Practicing Clinician. Gregoris Simos trained with me many years ago and is especially well qualified to have edited this volume. The chapters in this volume have been prepared by specialists in the various Axis I and Axis II Disorders and cover the full range of psychological disorders. I am particularly gratified that various of the authors have worked with me in the past. This volume is unique in its presentation of guiding principles and strategies by these experts. Cognitive Therapy, covered in this volume, draws on a very strong empirical base for its theoretical formulation. The generic cognitive model derived from the theory has been tailored to the specific characteristics of the Axis I and Axis II disorders. A large number of outcome studies have supported its efficacy in the treatment of primarily Axis I disorders. In addition to the earlier work with the depressive and anxiety disorders, the most recent controlled outcome studies have indicated cognitive therapy’s efficacy with or without medication in the more intractable and severe disorders, such as Severe Chronic Depression, Bipolar Disorder, Anorexia Nervosa, Schizophrenia, Chronic Fatigue Syndromes, and Substance Abuse. I would especially highlight new cognitive approaches to schizophrenia. As we enter the new millennium, we ask, ‘How can cognitive therapy best serve the changing needs of the patients and the payers of health care?’. In the future, I anticipate the emergence of a broad psychotherapy that will be refined for the broad range of psychological problems in psychiatric and medical patients. With changes in the delivery of health care, I expect that some kind of triage will assign psychotherapists according to their degree of expertise and specialized skills. In all probability less experienced, less skillful therapists will treat the simple garden-variety of disorders on a short-term basis (from three to twelve visits). The more skillful and highly trained therapists will work with the challenging Axis I and Axis II disorders in longer-term therapy, possibly in combination with drugs. This will include spacing the visits over a longer period of time than is customary presently and providing ‘booster’ sessions. 2 Introduction Many therapists will work as members of a team with primary care physicians. The therapist would be responsible for assessing and screening medical patients for psychiatric problems. Since 40–50 per cent of patients in a family practice have some degree of depression, these problems will be addressed by the primary care therapists. They will also be involved in the ‘disease management’ of disorders such as diabetes, hypertension, low back pain, and asthma. I predict that opportunities for well-trained, experienced therapists should increase. In the future the accreditation of therapists will be based on the assessment of their competency in dealing with patients, and they either will or will not be assigned to patients depending upon their ‘non-specific’ psychotherapy skills as well as their more highly specialized skills. I am pleased that this volume will provide a framework for present and future therapists to hone their skills. Aaron T. Beck, M.D., University Professor of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania Chapter 1 The cognitive treatment of depression Kevin T. Kuehlwein Impact of depression Depression in its various forms (major depression, dysthymia, the depressed phase of bipolar disorder) is both a highly disabling and disturbingly widespread phenomenon in today’s society. It causes huge suffering and economic costs to individuals and society because of both its high prevalence and its undertreatment among most segments of society (National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association Consensus Statement on the Undertreatment of Depression (NDMACS); Hirschfeld et al., 1997). Moreover, although effective treatments for depression exist, various factors on both the client and professional side prevent people from recognising the signs of depression and then receiving optimal treatment from qualified professionals. Depressed individuals often feel the stigma attached to problems of “mental illness”. This makes them reluctant to seek help in the earlier stages of the disorder before certain of their negative cognitive-affective-behavioural patterns have strengthened. Instead of simply realising that they may need professional help, depressed clients often label themselves as “weak” or “failures” (or fear others may do so) due to their increasing difficulty in handling many aspects of their lives. Recent studies on the impact of major depression have compared its negative effects to those of other chronic general medical ailments like heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes (Hays, Wells, Sherbourne, Rogers, & Spritzer, 1995). The monetary toll alone in the United Kingdom has been estimated at between £220 million (Jonsson & Bebbington, 1994) and £2500 million per year (including indirect costs) (Kind & Sorenson, 1995). Optimal treatment, furthermore, does not often occur because many professionals even in highly industrialised countries are themselves inadequately trained in both the diagnosis and treatment of depression, from both the psychotherapeutic as well as pharmacological angles. A few statistics will illustrate these points. • The lifetime risk of major depression in the United States and other countries has been reported to range from about 5 to 25% in women and from 2 to 12% in men (Boyd & Weissman, 1981). 4 • • • • Kevin T. Kuehlwein Of those who are depressed and see a health professional, the vast majority do not even encounter a mental health professional, but instead are seen only by a primary practice doctor (Hirschfeld et al., 1997). Because certain physical disorders can involve symptoms similar to those of depression, many examining physicians do not accurately or promptly detect depression in the majority of their patients. Therefore, they often neither treat the concomitant depression nor refer the patient to a competent mental health professional (Hirschfeld et al., 1997). Costs of actual treatment combined with diminished productivity resulting from major depressive disorder in the United States total approximately $16 billion in 1980 dollars (Hirschfeld et al., 1997). People with three or more episodes of major depressive disorder have a 9 in 10 chance of having a relapse into a further episode (Hirschfeld et al., 1997). Luckily, Beck’s cognitive therapy (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) has proved highly effective in many studies as a treatment for depression (Hollon & Beck, 1994). This chapter will focus primarily on the outpatient treatment of major depression in individual therapy with adults because the research has concentrated on that population. It is, however, possible to use this approach with milder types of non-psychotic depression and, with certain modifications, as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy with bipolar disorder clients. Indeed, therapists can use cognitive therapy with many clients on medications to increase their medication compliance. It has also been practised successfully in group formats (Hollon & Shaw, 1979; Freeman, Schrodt, Gilson, & Ludgate, 1993) and with children, again with certain modifications (DiGiuseppe, 1993). Structure of the chapter In describing an effective cognitive therapy approach to major depression, I will first define cognitive therapy, speak about the theory of cognitive therapy as applied to the problems of depression, focusing especially on conceptualisation, detail some techniques to use in assessing and treating depression, delineate steps in a typical course of treatment, and mention throughout common mistakes that even more experienced therapists may sometimes make in treating depressed clients. Finally I will offer suggestions throughout as to how to avoid many of these errors. Defining cognitive therapy Before beginning the discussion of cognitive therapy of depression, however, I want to emphasise that cognitive therapy is not a collection of useful techniques to be used in isolation. Indeed, Beck maintains that “cognitive therapy Cognitive treatment of depression 5 is best viewed as the application of the cognitive model of a particular disorder with the use of a variety of techniques designed to modify the dysfunctional beliefs and faulty information-processing characteristic of each disorder” (Beck, 1993, p. 194). Cognitive conceptualisation of depression According to Beck’s cognitive specificity hypothesis (Beck et al., 1979) depressed clients have a different cognitive profile from those with other psychiatric problems, showing primarily themes of loss, defeat, and failure in their cognitive content. Their spontaneous verbal output typically reveals many examples of thinking (including metaphors and images) with a systematic negative bias. This is mirrored in clients’ deeper, unspoken assumptions across many domains of their experience. Beck has especially called attention to the “negative cognitive triad” in depressed clients: a fairly unrelenting tendency to view themselves, the future, and their experience around them almost entirely in negative terms (Beck et al., 1979). Because of Beck’s focus in the cognitive treatment of depression on identifying, evaluating, and modifying dysfunctional thoughts and deeper beliefs, some careless readers of his work are under the misapprehension that Beck assigns a causal role in depression to distorted thinking. When questioned, he has said that he would no more make that claim than to suggest that hallucinations and delusion cause schizophrenia (Beck et al., 1979). While Beck is careful to avoid saying with authority what exactly causes depression in the first place, since research itself has produced no definitive answers, he maintains that the maladaptive worldview of depressive clients helps to maintain most of the symptoms of depression as well as significantly interfering with their effective problem-solving of their many real-life problems (Beck et al., 1979). In many cases, indeed, clients’ lack of effective action or their actually dysfunctional action flows from their maladaptive and overly rigid ways of viewing their situation. What cognitive therapy first seeks to do, therefore, is help clients to be more aware of their active ways of making meaning and to discover the adaptiveness or maladaptiveness of these constructions. This is called “decentering”, described by Safran and Segal (1990) as a process through which one is able to step outside of one’s immediate experience, thereby changing the very nature of that experience. This process allows for the introduction of a gap between the event and one’s reaction to that event . . . Stepping outside of one’s current experience fosters a recognition that the reality of the moment is not absolute, immutable, or unalterable, but rather something that is being constructed (p. 117). Safran and Segal note, however, that mere theoretical awareness of this process is insufficient to induce necessary change: “For change to take place, 6 Kevin T. Kuehlwein however, patients must have more than an intellectual grasp of this notion. They must have the experience of actually seeing themselves construct reality” (p. 118). After clients learn how to do this, their next task is to explore and learn to utilise other, more adaptive ways of understanding their own experience. As they practise this skill of disembedding from their dysfunctional constructions they become progressively better able to detect and resolve problems. It is important for every clinician to develop and share with the client on some level his or her evolving cognitive conceptualisation of the client. The conceptualisation has two major parts. The first part is the general conceptualisation of the phenomenon of depression itself. This more generic idea of the typical characteristics, predisposing factors, as well as the likely cognitive, affective, behavioural and situational vulnerabilities helps the therapist better understand many of depression’s common aspects. For example, the therapist can predict that a client will usually continue to feel bad if she spends a great deal of time oversleeping, avoiding most activity, and ruminating. The therapist can then educate the client about her own depression and what will tend to reduce or increase it. Educating the client in this way about the nature of depression can help her to break out of a sense of emotional helplessness (for example, “My moods just come over me and there’s nothing I can do, Doctor.”). This can help to reduce demoralisation in the client and impart an increasing sense of self-efficacy in her (for example, “If I work to catch and reduce my all or nothing thinking, I’ll feel better and enjoy things more” or “If I get up at 8 a.m. and plan my day with some forethought, I can feel satisfied during and at the end of the day”). The second part is an individualised case formulation for each client to answer questions like the following: How does this particular client experience depression? What are the most salient features for her? What possible sociocultural effects might there be that could affect her experience of herself and depression? How do the symptoms all fit together? Which component tends to start the negative cycle? What mitigating factors in her depression can we utilise to help the client break free of her depression? So, although the above-mentioned similarities exist across many depressed clients, each client has a depression that is also unique. Historical factors and current situations as well as the personal construction of meanings will differ for each client. For this reason, the therapist must develop an evolving, multifactorial conceptualisation of each client. Most clients find it very interesting and gratifying to explore and collaborate on this. The positive effect, again, of such activity is often greater self-understanding and greater self-compassion. This can also lead to an enhanced sense of control and predictability over their moods, thoughts, and actions. There are several models for developing such an individualised case formulation. Beck (1995), for example, has a Cognitive Conceptualisation Diagram (1995, p. 139) that serves as a quick summary sheet of the most important information gathered over the early Cognitive treatment of depression 7 part of therapy. Layden (1997) also has developed a slightly more differentiated one that places increased emphasis on images as well as more positive beliefs and experiences of the client. Persons (1989, 1993) has written a fulllength book and several chapters solely on the subject of conceptualisation. She has put forth a rather comprehensive model for understanding the major components of a client’s problematic patterns. Whatever model the therapist uses, the basic conceptualisation probably needs to cover at least the following areas: 1 Major current problems (including behavioural, cognitive, affective, and physiological) the client is experiencing. For example, one might note that a client is depressed, sad, and nervous; tends to withdraw socially, drink alcohol every evening, and watch TV at home; tends to experience headaches and constant fatigue as well as a gnawing pain in her stomach; tends to blame herself for anything that goes wrong, tells herself that she really should pull herself up by her bootstraps and snap out of it, calls herself a loser and failure, and predicts continued misery and isolation for the rest of her life. 2 A few representative situations in which these problems occur with the unique behavioural, affective, cognitive, and physiological aspects noted. For example, a client becomes especially depressed and fatigued and withdraws from social contact whenever she receives criticism, even if well-intentioned. She then says to herself, “They must be right. I can’t do anything right. It’s just like my ex-husband used to say, I am a failure.” 3 Current predisposing events and situations. Example: mounting debt, death of a loved one, highly stressful job. 4 Any metaphors, similes, images, or dreams the client reports that represent important aspects of the problems under review. Example: a client’s image of herself wrapped in chains in a cold, dark room and unable to move. 5 The current cognitive, affective, physiological, and behavioural strategies that seem to represent coping attempts (even if of questionable utility in the long term). These, sometimes referred to as “compensatory strategies” (Beck, 1995), are reactions to the underlying negative core beliefs that cause the client to experience distress. Examples: frequent blotting out of unpleasant facts via forgetting or substance abuse, being overly dependent on others, procrastinating, or criticising oneself before others can. 6 Past predisposing situations (especially those that had a large impact on the client as a developing child or those later in life that were so disturbing as to shake the very foundations of her meaning-making structures at the time). Example: the tragic loss of a close friend from a car accident years ago, which led a client to question the very concept of safety and trust in the world. 8 Kevin T. Kuehlwein 7 Past situations of good coping during stress or change. Example: a client took a year abroad in Portugal as a break from college and managed to learn Portuguese quickly and to begin a small business at which he was very successful. 8 Past accomplishments. Example: a client was one of the top students in his college class. He also was told by a professor whom he respected that a paper he wrote for a course should be slightly rewritten and published because it was so creative. 9 Interests and passions. Example: a client is very interested in all kinds of sports and follows baseball especially avidly. These interests can often be used by the knowledgeable therapist as a source of useful linking metaphors to counter dysfunctional beliefs. 10 Past or present people who have had a positive impact on the client. Example: as a child a client was taken care of by a woman in the neighbourhood after school during a brief period when his mother worked full-time outside the home. This older much more maternal woman was very affectionate, empathetic, and understanding of the needs of the client as a 6-year-old boy. As an adult, this client still associates the smell of baked goods with fond memories of her (see also above section on images). Another positive force in his life is his very kind wife, who has stood by him during periods of great turbulence in their lives. Therapists will benefit from having a several-page form with these headings to contain all of this information, so that they have easy accessibility to a client’s relevant treatment factors all in one place. Many therapists when they conceptualise their clients have a primarily problem-focused orientation and thereby risk viewing their clients solely through the lens of their current relatively poor coping. The advantages of examining also the more positive effects (past and present) on the client are that the therapist gains a much fuller understanding of the client in all her complexity. Gently enquiring about such positive events and resources in the client’s life can also help the client to gain better access to those memories and those parts of her experience. The therapist can then use her knowledge of these more positive forces in the client’s life to build bridges from the past and current strengths out of her present difficulties and into the more positive future. It is key when doing this, however, to ensure that the client does not believe that the therapist is invalidating her view of the world. Instead the therapist should convey an attitude of trying to provide a needed balance between the negative and positive aspects of her life. Note that both positive and negative outcomes early in therapy serve to inform therapist and client about the accuracy and utility of the evolving treatment conceptualisation, so that unexpected results (for example a poor result from an attempted intervention) should lead the therapist to modify her case conceptualisation and resulting therapy approach. Cognitive treatment of depression 9 Diagnosis It is very important to begin therapy with a good, preferably standardised diagnostic assessment (SCID I & II; Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1990) of the client and her whole range of presenting problems. This multi-axial assessment (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) should include specifically targeted diagnostic questions to help the therapist determine what the duration, quality, and severity of the depression is as well as any accompanying conditions, whether they be comorbid psychiatric disorders, comorbid physical disorders, or simply environmental situations that may affect (positively or negatively) the depression or the treatment. It is helpful, for example, to know if the client is also suffering from an eating disorder or obsessive compulsive disorder since experts recommend these other Axis I disorders generally be treated first before trying to approach the major depression (Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR), 1993a, 1993b). If the client is also comorbid for panic disorder, the therapist must determine which disorder is primary before deciding which to treat first. When treating a client who meets criteria for substance abuse, the therapist generally should first focus on getting the client to discontinue the substance (via a detoxification programme) and then re-evaluate the client’s condition 1–2 months afterwards. If the client continues to experience major depressive disorder, then that becomes the focus of treatment. In some situations, however, it may be advisable to treat the major depressive disorder earlier (AHCPR, 1993b). A good assessment will also help the therapist ascertain the last time a client received a medical check-up that would rule out some of the many organic causes of depression (Cassem, 1988). Problem assessment Of course, cognitive therapy strongly focuses on the careful assessment of problems both before and throughout the treatment. This emphasis ensures that the therapist fully understands the full scope of the many problems (as well as their interrelationships) and attends carefully to the changes in symptoms during the course of therapy. If change does not occur or is not in the desired direction (that is, the client’s symptoms worsen contrary to expectations), therapist and client can then notice this sooner and modify the treatment approach accordingly. Cognitive therapy focuses on what is going on in the client’s current experience (versus the distant past) as of primary importance in alleviating and preventing distress. Therefore, a therapist need not gather exhaustive information about the past difficulties of a client at the outset of therapy, although some background information is, of course, important. The therapist instead gathers a comprehensive problem list of the major problems across many modalities that a client currently experiences. For example, the therapist would inquire about work and relationships – 10 Kevin T. Kuehlwein relationships with family, friends, partners – and other relevant potential support mechanisms or stress-related factors. He would also ask the client about her nutrition, substance use (including caffeine and tobacco), and exercise/activity level. Many therapists overlook these physiological factors, which can sometimes significantly affect a client’s depression or recovery from depression. The author has known, for example, several clients for whom regular exercise was an absolutely integral part of improving their mood states. In other cases, modifying odd patterns of nutrition seemed to support more adaptive thinking and action. Clear descriptions of problems and progress One of the most common impediments early in therapy is when clients define their problems and goals too vaguely. It is not at all uncommon to hear clients come in with the goal of being happy without clarifying questions like these: “What am I most unhappy about? What about that makes me unhappy? What would need to change for me to be more happy? When am I happiest? How do I behave when I am happy? What are the behaviours most associated with being unhappy?” Having vague goals begets vague therapy: wandering around from topic to topic without any sense of focus or progress. As a general rule, if the therapist cannot form a clear picture either of the problem or its solution then the client needs to clarify it further. Ideally most goals should be able to be measured in terms of frequency, intensity, and/or duration. Example: “When I am less depressed (global goal client is likely to desire), I will be sleeping 8 hours/night 5 nights a week and not getting out of bed in the middle of the night” (operationalised definition of this goal). Having clients complete validated symptom checklist scores – such as the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, 1978), Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988), and the Beck Hopelessness Scale (Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, 1974) – that the therapist briefly reviews at the beginning of each session is another good way to assess ongoing progress. Symptom relief Obviously, one of the first things the therapist wants to provide the client with is symptom relief since most depressed clients come in feeling quite distressed and will not continue to attend therapy if they do not experience some degree of amelioration soon. Keying in especially to the cognitive and behavioural components of a client’s distress, the therapist may within the first session begin to explore the client’s constructions of her experience and identify possible ways in which she can transcend these by adopting alternative perspectives. Depressed clients, for example, often come in with a sense of personal deficiency such as, “I am a failure.” When client and therapist explore this more deeply, it often reveals a rigidly applied underlying belief, Cognitive treatment of depression 11 “If I do not fulfil my responsibilities [often quite difficult when one is depressed], then I am a failure.” It can often be somewhat helpful for such clients simply to label this as a strongly held belief rather than a universally acknowledged truth that everybody unquestioningly believes. By introducing the idea that problems primarily result from our dysfunctional interpretations of situations rather than the situations themselves, the therapist can help a client to frame her problem quite differently as one which has possible solutions rather than being hopelessly insoluble. An example of this follows: If I’m hearing you right, you’re awfully discouraged about any possible solutions to your current problems with your daughter. In fact, you’re so pessimistic that you’re actually on some level saying, “I’m just a bad mother or she wouldn’t act that way!” How close does that sound? OK. I’m proposing that we explore how your depression and problems with your daughter might be linked to how you view the situation. For example, if you view things as hopeless, how might you act? Right, you’ll probably give up and not even search actively for any solutions. But how would things be if you act out of a very different belief like “She can really act up, but she’s basically a good kid; we just need to understand each other a bit better and I’m sure we’ll come to a better working relationship”? How do you think you’d feel and act if you saw things that way? Probably more calmly, less blaming of yourself and her and more likely to look for the possible areas of agreement and solutions. Sure. That’s a lot of what we’re going to be doing in here: taking a closer look at how you view things and how there may be other, possibly more adaptive ways you could also see things: new ways that could indeed lead to better ways of feeling and more helpful ways of acting both with yourself and others. One idea of cognitive therapy is that we’re often not very good at problem-solving when we’re most upset, so we want to distrust our tendency to think in global, pessimistic ways. We know from experience that we rarely make any progress toward solving our goals when we think that way. So you want to stop and take the following steps when you’re upset. 1. Identify what’s going through your mind (automatic thought or image or deeper belief). 2. Evaluate how adaptive or accurate that is realistically. 3. Modify that if it looks like there would be more adaptive ways to view the situation. Don’t forget you’ve got a consultant here to help you do all that, so you’re not alone in any of this. You will gradually learn how to do this more and more on your own as you recognise the negative cycles earlier and earlier. How does that all sound? Course of therapy Early goals for cognitive therapy (the first 1–2 sessions) include the following: (1) developing a good therapeutic alliance, (2) specifically defining target 12 Kevin T. Kuehlwein problems, (3) determining which problems are most important, (4) increasing hope, (5) clarifying the integral relationship between beliefs, affect, and behaviour, (6) beginning to socialise the client into the cognitive therapy model, and (7) emphasising how critical regular homework is to the success of therapy. In the middle section of therapy (approximately sessions 2–10) these are the most important goals: (1) teaching the client about cognitive distortions, (2) identifying, evaluating, and modifying his/her dysfunctional cognitions, (3) experiential testing of targeted client beliefs, (4) refining and practising social skills, including problem-solving strategies. In later sessions (approximately session 11 to the last) the focus shifts to (1) eliciting, examining, and modifying deeper cognitive structures (for example, conditional assumptions and the rigid, dysfunctional core beliefs) and, in the last few sessions, (2) relapse prevention, including in-depth review of the most important lessons learned in therapy and prediction of future situations likely to trigger dysfunctional cognitions, behaviours, and affects as well as pre-problem-solving of these: developing written plans to suggest likely plans of action for coping with these types of problems (Wright, 1988). Therapy according to Beck’s model proceeds inductively. Initially therapist and client explore concrete, specific time-limited situations in the client’s current life (for example, a disappointing phone call from a friend the previous night). As they gather more information about typical situations associated with dysfunctional affect, behaviour, or cognitions (including images and metaphors), they together build a more differentiated and individualised conceptualisation of how behaviours, situations, emotions, bodily symptoms (for example, pain), and cognitive content fit together. This enables the client to develop increasing distance and ability to see her beliefs as beliefs (versus as truth). After developing some competence at identifying, evaluating, and modifying situation-specific dysfunctional automatic thoughts (ATs), client and therapist move on to applying these decentring skills to examine and modify deeper level beliefs that cut across many situations. Examples here include what makes people worthwhile or lovable; what constitutes success; what level of control is necessary in life; how much you can trust others or the world. It is these deeper level beliefs and assumptions that provide the dysfunctional depressive template for meaning-making for the client across many situations, so it is critical that therapy involve collaborative reconstruction of these deeper meanings. Without such reconstruction the client remains very vulnerable in thematically related areas which therapist and client have not yet formally examined. Further, the client is then very vulnerable to relapse after treatment ends, which is a common problem in depression treatment in general (Hollon & Beck, 1994). One of the hallmarks, indeed, of cognitive therapy is its ability to instil in the client a set of metacognitive skills that (when practised) provides great protection against future relapse after termination from therapy (Hollon, 1996). Cognitive treatment of depression 13 Therapy sessions are frequently packed with a huge amount of information about both the client’s current and past life and encompassing a wide range of modalities: behaviours, beliefs, emotions, and physical symptoms. In addition, the therapist can attend not just to the content of what is being said, but to the process of how it is communicated and the feelings it engenders within himself. All these data must be sorted through to determine what is most key to focus on in each session in order to promote cognitive (and ensuing behavioural and affective) change. A good general rule is, “Follow the affect.” When a therapist pursues those cognitions most closely tied to high affect, he is more likely to help the client identify, explore, and reconstruct those deeper meanings most tied to her present and future distress. Alert therapists will therefore pay especially close attention to a client’s change in body posture, hesitation at answering a question, eyes beginning to tear up, and the like. These are prime points at which to ask, “What’s going through your mind just now?” to elicit the thought/image that is triggering an emotional reaction. Likewise, a wise cognitive therapist will rapidly sense (by noting the lack of high affect) when discussion of certain agenda items is peripheral to meaningful change. At this point the therapist will call the client’s attention to this fact and elicit collaboration to proceed to more critical issues. Socialisation throughout therapy Some therapists mistakenly socialise the client into cognitive therapy only briefly at the onset of therapy. Instead the therapist should promote ongoing socialisation into cognitive therapy and the cognitive model of depression throughout the course of therapy. The therapist might introduce the most important aspects of the cognitive model in a way similar to this: Cognitive therapy is a modern therapy that is both very interactive and problem-focused. It’s based on the idea that the ways you interpret situations have a very strong impact on how you feel about and behave in response to those situations. When somebody is depressed she’s not always seeing things clearly. Everything has a negative cast to it and certain problem-solving options are hidden from view. Let’s think of an example. Suppose you thought that nothing could help you with this depression and you believed that idea 100% – not a doubt in your mind. What emotion and behaviour would follow from that? Right. You’d feel hopeless. And where would you be? Not here in therapy, would you? Now, what would happen to your depression if you didn’t show up for therapy? Not much, right? See – before even trying therapy to help you solve your problems, you might have shut the door on problem-solving. So you want to be more aware of how you’re actively construing situations. It’s important to identify and evaluate especially those thoughts, assumptions, and beliefs most associated with downturns in mood or 14 Kevin T. Kuehlwein with maladaptive behaviours because in many cases there are other more adaptive and/or accurate ways of viewing the same situation. I want to emphasise, however, that these cognitions we want to investigate can occur in many forms, including verbal or visual form. Often when we’re upset we get quick mental pictures in our minds that are very unhelpful to us, but we don’t stop to question them. In cognitive therapy you’ll learn all about how to identify, evaluate, and modify dysfunctional beliefs and therefore increasingly be able to be your own therapist. We’ll share with you a great deal of information about depression and help you to understand how all your feelings, beliefs, behaviours, and bodily symptoms interconnect. We’ll also teach you how to best use this information to break free of depression. How does that sound? In addition to introducing the cognitive therapy model in such a fashion, the therapist may want the client to read one of several pamphlets or books that explain the model and the treatment further. Helpful examples of these include the following: Coping with Depression (Beck & Greenberg, 1974), A Patient’s Guide to Cognitive Therapy (Center for Cognitive Therapy, 1993), and the sections on client booklets (Fennell, 1989), or The Feeling Good Handbook (Burns, 1989), a full-length cognitive therapy self-help book. The author frequently uses Socratic questioning to underscore the important tenet that the client’s own efforts are responsible for her improvements in mood. When a client comes in feeling better, the therapist could ask a question like the following: “Margaret, you just said that you felt a lot better this week. How about if we put on the agenda to discuss exactly what it is that you’re doing differently that accounts for this?” The therapist thus subtly but unmistakably attributes the positive change to the client’s own efforts whether they be internal (beliefs) or external (behaviours, which in turn are supported by internal changes). The client is thereby directed to look for what she might have done differently that week. Often clients are initially surprised at the therapist’s attribution of change to their efforts, feeling as they often do helpless to control their moods. The therapist in casting the client’s attention on her own efforts can thereby help to undermine the client’s perceived helplessness as well as increase belief in the idea that there are discernible reasons for upswings and downturns in mood. Structure and agenda setting To maximise the effectiveness of time and effort, it is essential that the therapist and client structure the therapy sessions. As part of the early socialisation process the therapist socialises the client into the importance and process of agenda setting: what constitutes a reasonable agenda and the need to set priorities of agenda items. Too often therapists begin a session by asking the overly diffuse, “How are you doing?” For many clients this is Cognitive treatment of depression 15 equivalent to asking for a detailed report. It is more efficient for the client to fill out prior to the session certain symptom checklists – for example, the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, 1978), Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck et al., 1988), and the Beck Hopelessness Scale (Beck et al., 1974) – so that significant mood shifts can be noted and possibly added to the agenda. The therapist can then comment on the client’s apparent mood for the week and elicit the client’s brief response to this. Too often therapists will ask clients, “What would you like to discuss this week?” This does not set up a work orientation for the session and, indeed, may elicit more of a conversational type of discussion. Far better is something like, “Besides bridging from the last session and reviewing the homework, what problems would you most like us to work on today?” This latter type of question adds the bridge from the prior to the present session, indicates that homework will be discussed, and invites the client to present only those other agenda items which are problems and on which she is willing to work. This will produce a manageable but useful agenda. Typical agenda items for a 45–50 minute session would then include bridging from the prior sessions (including any reactions that the client had about this session), review of homework, prioritisation and discussion of 1–2 new topics, summarising the session’s main points, setting the new homework, and eliciting feedback on the current session. Indeed, client feedback is an integral part of cognitive therapy. The wise therapist frequently asks how the client perceives him and the process of therapy as well as what the client is learning from the session. Questions like, “What are you learning here?” or “What new idea did you get from the homework?” are good to focus the client toward the development of new, more adaptive ideas. “How much sense does this make to you?” can also help the client provide the therapist with needed feedback on better explaining a point in therapy. It is good to probe for any strongly positive reactions to the therapy so that the therapist can better understand and repeat the approaches that maximally benefit the client. Likewise, it is key for the therapist to enquire whether the client has been upset or offended by something in the session so that this can be processed and addressed as soon as possible. Frequently such early negative feelings and thoughts that clients have toward the therapy or the therapist can be a boon to the therapy if they are elicited and examined. The therapist, by his non-defensive, gently inquiring, and empathic way of attempting to understand and honestly address the client’s concerns, often allays any worries the client may have of therapy being mechanised or overly cerebral, for example. From the first session onward therapists need also to elicit and address, where necessary, clients’ expectations about the therapy and the therapist (both positive and negative, realistic and ideal). Therapists present from the outset a model of cognitive therapy progress that is not ideal, but is rather realistic in its depiction of progress that includes occasional small setbacks. 16 Kevin T. Kuehlwein Obviously if a client indicates that she has more than incidental suicidal ideation, then suicidality becomes the top agenda item. This is addressed more fully in a later section, “Addressing suicidality”. Homework How much clients outside therapy think about and act on the ideas discussed in sessions will determine the speed and depth of therapy progress. Several researchers have found the performance of such in-between session tasks, “homework”, to be critical to successful outcome of therapy (Persons, Burns, & Perloff, 1988). It is therefore helpful for therapists to assist their clients in thinking about the ideas discussed in therapy and provoking new thought by helping their clients locate good companion texts and providing them with certain types of handouts or booklets to read and/or fill out. Therapists may wish to draw up their own handouts specifically tailored to the types of problems most commonly encountered in their own practice. Clients benefit from having separate brief 1–2 page handouts for topics such as these: types of cognitive distortions, questions to help them evaluate their possibly dysfunctional thoughts/images, a sheet (for example, the Dysfunctional Thought Record; see Appendix 1.A, p. 41) with blanks that represents a format for writing down their thoughts/images associated with distress and more adaptive replies to these thoughts. The author uses also a sheet of quotes from various sources that are in some sense supportive of the underlying assumptions of cognitive therapy (see Appendix 1.B, p. 44). Bibliotherapy – the reading of certain texts concurrent with therapy – is also excellent homework for most clients to expand on points covered in the sessions. There are several good books available that describe the cognitive therapy model in sufficient detail. The Feeling Good Handbook (Burns, 1989) and Self-Esteem (McKay & Fanning, 1992) are especially good. Clients who are very judgemental or have impossibly high standards may benefit from The Spirituality of Imperfection (Kurtz & Ketcham, 1992). A useful guide that can also give cognitive therapists some assistance in choosing appropriate bibliotherapy for their depressed clients is The Authoritative Guide to Self-Help Books (Santrock, Minnett, & Campbell, 1994). Whichever books (or tapes for those clients who may be visually or reading-impaired) the therapist chooses, it is good for the therapist to be familiar with them so he or she can intelligently answer any questions the client raises. The author strongly encourages clients whenever possible to buy and mark up (for example, using a “highlighter” pen for emphasis in certain passages) the self-help books. In this way clients can really interact with the material in the book. Clients also find that they deepen their understanding of the cognitive therapy approach if they explain it to a friend, relative, or partner. Of course there are many types of tasks in addition to client handouts and reading that clients can usefully do for homework, many of which appear Cognitive treatment of depression 17 later in the sections on behavioural and cognitive techniques. The basic rules for cognitive therapy homework are these: 1 2 3 4 5 6 It should be collaboratively agreed upon. Although it need not be a jointly conceived task, both parties should agree that it could further therapy goals. Often it will help answer a question posed in therapy (for example, “Am I unable to experience any pleasure whatsoever, as I often believe?” or “What would happen to my mood if I call and get together with my old friends again instead of avoiding them?”). It should be no-lose in its conception. The client should be able to learn something useful from the task, regardless of whether the outcome was expected. Sometimes clients’ ATs are fairly accurate, for a variety of reasons, and if a therapist sets up a situation where he clearly believes a client’s construction of reality is wrong but his (the therapist’s) is right, that sets up a dynamic in the therapy where each attempts to prove the other wrong. It also undermines the therapist’s credibility if the client brings in data to support her AT when the therapist has assured the client that a different outcome will result from performing the homework. The homework and its purpose should be clear to both parties. For example, “In order to better understand the connection between your moods and your activities, what would you think of jotting down what activities you are currently doing when you find yourself feeling more sad or depressed this week?” To this end, it is important for both therapist and client to write down homework tasks. It should flow logically from the session. Some therapists miss this point, believing that the client should do for homework something related to an agenda item for which there was insufficient time in the last session. This sets a bad precedent and does not help clients amplify their understanding of concepts explored in the session. It should be reviewed in the next session. Nothing extinguishes the adaptive behaviour of homework completion like the therapist’s behaviour of omitting discussion of the prior week’s homework. Good therapists will add it explicitly to the agenda verbally in the beginning of the session and will typically discuss it before moving on to discuss other topics. “OK, let’s review how the homework went” is often a good introduction here. Problems with homework compliance should be put on the agenda. “Hmm. I notice that you didn’t get around to doing the homework. I’m wondering what happened there. Let’s put that on the agenda, OK?” might be a neutral way of exploring the reasons behind homework noncompliance. Again, it is important for the therapist to convey an attitude of interested enquiry rather than criticism in this arena, which is often rife with guilt and accompanying ATs on the client’s part. Indeed, many times discussions on this topic can uncover some important underlying 18 Kevin T. Kuehlwein attitudes of the client toward authority figures, their own feelings of inadequacy, and the like. Some clients will go so far as to label themselves “a bad client” when they admit that they have not done their homework. Such an idea obviously says much about their dysfunctional beliefs that can be profitable to examine. Some other ideas about non-compliance are addressed later in this chapter. Exploring deeper levels of cognition As the therapy progresses it is, of course, necessary to explore and help the client discover, understand, and modify the deeper level beliefs that undergird dysfunctional affective, behavioural, and cognitive patterns. It is therefore critical for therapist and client to look for themes across the major ATs, images, and problematic situations and to add these to the evolving conceptualisation of the client. These deeper level beliefs typically involve such themes as clients’ ideas of how loveable or acceptable they are to important others, how much control or responsibility one has or should have for events that occur (negative or positive), what is required for happiness, how life should be, and what is meant by competence or success (Safran, Vallis, Segal, & Shaw, 1986). They also are often linked with clients’ ideas of trust in others and the world to respond to and provide for their needs. Many times these beliefs will determine the expected role for them and others in the world. For example, some depressed clients may believe “Nothing should be difficult. I shouldn’t have to work at anything.” This would obviously be a dysfunctional belief for a therapy relationship, putting all of the burden on the therapist to make the client better. When the therapist helps the client discover and examine these deeper beliefs (see also later section on cognitive techniques), the therapist wants to be careful not to convey explicitly or implicitly a judgement of the client for holding these beliefs. Indeed, doing so would only increase the therapist’s countertransference feelings (Newman, 1994). Rather, what is more helpful at this stage is for the therapist to explore both the historical origins, accuracy and/or ultimate utility of these ideas. The therapist can, for example, ask Socratic questions such as the following to help the client step back from these attitudes and examine them and their effects more critically: “Tell me, what are the advantages of that belief ? What good things have resulted from your operating out of it? What disadvantages might there be to that belief ? What opportunities have you missed by holding this belief in all situations? How would you compare these advantages to these disadvantages? When did you first realise that this was a rule for you? Where did you come up with this guideline? Who else do you know who operates out of this or a similar belief ? How happy would you say that person is? Can you see any advantages to modifying this belief slightly, where it would be to your long-term benefit, for example? What do you think would Cognitive treatment of depression 19 happen if you experimented with less rigid beliefs in this area, for example, ‘I’d like things to be easy for me, but probably not everything will be and that doesn’t have to be catastrophic.’?” These sorts of questions can help clients pry themselves loose from the grasp of very dysfunctional beliefs that few people have invited them to explore. Indeed, the therapist encountering such client beliefs (and any accompanying frustrating countertransference feelings) should realise that many of these dysfunctional beliefs and behaviours being displayed were at some point at least somewhat adaptive for the client (Newman, 1994). The problem is that they are now overly rigid and therefore too absolutely applied and in too many situations in the client’s life for them to work well. Note also that in most cases the client may also have countervailing beliefs of a more reasonable nature. These more adaptive beliefs are typically, however, currently overshadowed by the stronger dysfunctional attitudes triggered by the client’s depressive mode. An important task for the therapist is to help the client uncover and appreciate these more adaptive beliefs. The next therapeutic task is coaxing forth such adaptive cognitions and strengthening them via Socratic questioning about past and current experiences of success and coping (see also later section on cognitive techniques). An elegant example of such questioning appears in a videotaped therapy session of Beck working with a depressed woman who experiences a great deal of pain about her current relationship. One of the things that most depresses her is the thought that she can never be happy without her husband. Through a series of related Socratic questions Beck helps her to remember that the time before she met him was actually better than her current situation, thereby assisting her to see that this man is clearly not integral to her happiness. Specific techniques In doing cognitive therapy with depressed clients the therapist should realise that there are specific strategies leading to therapeutic improvement, but also that cognitive therapy is not a collection of disembodied techniques to be used in random fashion, one after the other. Techniques are only as good as the conceptualisation from which they spring. A good therapist, for example, will appreciate the nuances of teaching the Dysfunctional Thought Record (DTR) to a depressed client who also meets criteria for avoidant personality disorder. This type of client will typically experience higher sensitivity to criticism from others (even when unintended) so the therapist must tailor the teaching of this tool to this individual. This would involve being especially alert to any signs of the client feeling rejected, criticised, or inadequate during this process and actively probing for any negative feelings after the exercise. The following comment and question is an example of how the therapist might successfully elicit honest feedback about the therapeutic process midsession from a client: “You’ve mentioned that you often feel criticised by 20 Kevin T. Kuehlwein others. I’m wondering to what extent you felt criticised by anything that’s happened here today.” Given that certain clients, especially at the beginning of therapy, would be reluctant to criticise the therapist, he might proceed a bit further upon getting a denial and ask the client, “How easy or difficult would it be for you to tell me if you did feel criticised by something I said or did?” In this way, the therapist would be most likely to elicit and then process any possible distortions in the therapeutic relationship before they became harder to manage. In keeping with a differentiated case conceptualisation the therapist would likely use different strategies at different stages of therapy. For example, it is more common to teach techniques such as cognitive distraction earlier on, when the client is first learning the model. This technique helps to provide quick, albeit temporary, relief and can illustrate to the client with her own data that her focus of attention largely determines her mood and behaviour. Note, however, that this technique does little to explicitly identify, evaluate, or modify dysfunctional beliefs or behaviours, so it would be a huge mistake to overuse this particular technique. Behavioural techniques Activating the depressed client is of prime importance because of the tendency for the typical client to withdraw from normal activities that could provide pleasure and then to spend the resulting free time in negative rumination, which further depresses her mood. Behavioural activation techniques are therefore often most important in the early stages of therapy, especially with clients who are most depressed. Not engaging in useful or pleasurable activities robs clients of many opportunities to feel good about themselves and increases self-blame and dread about the future. These clients therefore need to become more active in certain specific ways. Chief among these behavioural techniques are activity planning and scheduling. Both involve keeping an Activity Chart, a simple weekly form with empty boxes for each reasonable hour of the day and night. Clients can fill this out prospectively (especially helpful if they are unsure how to fill their time) or retrospectively, right after they complete a task (good to track their actual versus reported behaviours). Additionally, the therapist can ask the client to indicate the level (0–10) of pleasure (for example, P = 6) or accomplishment (for example, A = 2) beside each activity so the therapist can note and explore any unusual patterns. Clues to ATs or images that may interfere with a sense of accomplishment or pleasure can often be detected via very low reported levels of pleasure or accomplishment compared to what one would expect associated with these activities. By having the client fill out an Activity Chart retrospectively the therapist can gather early in therapy more precise information about the client’s typical day. He can, for example, observe the amount of and balance between Cognitive treatment of depression 21 leisure/pleasure and task-oriented activities. Patterns that are dysfunctional (for example, oversleeping, avoidance of necessary tasks) can then be noted and corrected. In addition, clients will be able to actively experiment with the possible positive effects on their mood of engaging in certain old and new activities. This underscores empirical aspects of the cognitive model in the client’s own mind by using their own data – harder for them to discount – to evaluate their beliefs. It also gives clients increased confidence in their ability to display some control over their dysphoria. Given that clients often show little confidence in their own ability to positively affect their moods – instead seeing the moods either as random or inevitable – this type of intervention can be quite powerful. A third reason for this intervention is that it actively challenges clients’ beliefs about how little they do or can do in other spheres of their lives since it challenges the more general sense of helplessness. In this sense all “behavioural” techniques are also cognitive in their desired effects. They are a means of actively testing beliefs such as “Nothing will make me feel better,” “I can’t do anything,” or “I’m not accomplishing anything during the day.” Therefore many techniques are neither purely cognitive or behavioural. Reducing helplessness Many times clients will claim that they can’t or couldn’t do some activity that was probably in their best interests to perform. Helping clients realise that they can perform these actions – although not as easily as before – is a key step in therapy. Therapists can thus ask questions like these, “When you say you can’t do X, how do you mean that? Are you physically unable to do that? Able but not very motivated or energetic about it? Or is it just harder to do than before you were depressed, but you can do it if you push yourself ?” Often that will help clients realise they are not as helpless as they feel. (This is often a great opportunity for the therapist to illustrate the cognitive distortion of “emotional reasoning”.) Another question that can help clients is this: “If you were in bed thinking that you just couldn’t pull yourself up out of bed and get going with your day and suddenly noticed that the far edge of the bed were on fire, what would you do?” Typically clients answer that they would somehow manage to get up and see the difference between true and perceived helplessness. Discussion of “I can’t” offers a great opportunity to illustrate the negative effects on emotion/motivation and subsequent behaviour of accepting such dysfunctional assumptions unquestioningly. Graded task assignment, another behaviourally focused strategy, is used especially when clients feel overwhelmed by the perceived enormous size of a certain task. In this technique the client breaks down the task into smaller, more manageable segments and then focuses on the easier parts of these in turn, so as to minimise any feelings of being overwhelmed by the entire task. This not only typically reduces fear in the client, but it also increases a sense 22 Kevin T. Kuehlwein of self-efficacy (for example, “I can do this if I only slow things down and work on each segment in turn”), which can then generalise to other tasks. Exercise and relaxation Many clients can greatly benefit not only from these types of behavioural approaches designed to reduce depressive affect, but also from various types of physical exercise and relaxation training. Most depressed clients experience high levels of anxiety as well as depression, due to their negative view of the future and their low level of confidence in their abilities to handle life challenges. For this reason clients may benefit greatly from learning techniques to interrupt anxious sequences in their lives. Bourne (1995) offers many such useful techniques to teach clients. Many clients also report exercise to have anti-depressant effects as well as to improve their sleep–wake cycle disturbances. As well as helping clients to show themselves that they can do something when they tend to disbelieve this, exercise actively stimulates the production in the body of certain natural chemicals that improve a sense of well-being. Cognitive techniques There are a multitude of cognitive techniques available to therapists, not all of which can be explained in this chapter. For a more extensive review see Beck (1995) and McMullin (1986). Metacognition and empiricism Therapy is always a collaborative enterprise with the client trained from early on in therapy to learn and practise skills of metacognition – thinking about her thinking. Emphasis is on the empirical: what actually happens versus what the client envisions will happen. In this way the client discovers certain inconsistencies and maladaptive tendencies in her ongoing construal of the world. There is no struggle for whose view of a situation – the client’s or the therapist’s – is correct. Indeed, when therapy is done well, typically therapist and client co-create meanings that are individually suited to the client’s life. To this end, one of the common cognitive therapy approaches involves creatively juxtaposing certain aspects of clients’ experience so as to provide optimum disequilibrium and perturbation of knowledge structures. For example, one might help a client who believes she has always been a failure to explore whether everybody would agree that she had failed at everything and search for examples of exceptions, where even the client herself admits to at least partial success in some arenas. One of the most important yet often hardest tasks for depressed clients when they first come in for therapy is to identify their automatic thoughts and Cognitive treatment of depression 23 images. This is not surprising, since the nature of ATs is to be so automatic that they at first appear only peripherally in one’s awareness and are gone too quickly to adequately explore them, their adaptiveness, or their accuracy. For this reason it is crucial for therapists to educate clients about the type and nature of ATs early on in therapy. Sometimes the therapist can jot down obvious ATs of the client that emerge spontaneously within the first session and share these with the client as examples. It is often helpful for a therapist to offer some examples that he has heard from other clients in their depressed phase of treatment. For example: It’s very common when clients first come in to have the following sorts of thoughts running through their heads, although at first they are not wholly aware of these: “Oh, god, this is such an effort. Here I have to tell my story to a complete stranger. He’s probably not even going to be able to help. What on earth am I doing wasting my money on this? I might as well give up.” I wonder if you’ve had any of those or similar ones while you were thinking about coming here for help? Therapists should further provide clients with clues as to when they are most likely to find ATs and images: typically when they have just experienced a negative shift in mood. Sometimes clients find this easier to detect via a change in a physical symptom (for example, tension in the stomach or sighing). A therapist could present it to clients in a way similar to this: Remember when you sighed loudly earlier in the session and I asked you, “What’s going through your mind right now?” Well, I was able to tell that an AT or image just went through your mind at that time because of your sigh. When our mood changes there are often physical markers for dysfunctional thoughts and images. This includes things like sighing, tensing certain muscles of the body, headaches, stomach upset, changes in breathing, sweating, and the like. So when you notice yourself suddenly feeling more upset or tense, what’s usually happening inside you? Right, you’re probably believing some sort of dysfunctional thought/image. So what’s the all-important question to ask yourself at that time? Good – “What’s going through my mind?” How about if we practise that sequence just for a moment now to really drive that point home? Let’s do the “OMIGOD!” response: take a sharp intake of breath as you think, “Omigod, what’s happening to me now!” THEN you notice this reaction and say, “Wow, I must have just had an AT/image. What was going through my mind just then?” Good! Now, how likely are you to remember that the next time you get upset? Excellent. Of course, nobody catches all their ATs and you don’t have to. It’s just important to be able to catch some of them, especially when you’re most upset. And writing them down helps you and I examine them more closely. In this way you 24 Kevin T. Kuehlwein can better understand how they might be maladaptive for you. You can also see how there are other ways to understand the situation that are going to work much better for you in terms of solving the problems you’re facing. How does that sound? Socratic questioning Socratic questioning is, of course, a primary in-session cognitive technique. Here the therapist opens up a client’s way of viewing herself and/or the world by means of guided discovery involving primarily open-ended questioning (Overholser, 1993a, 1993b). This series of questions explore the personal meanings attached to certain phenomena and the relationships between different parts of the client’s experience. The author has found that many cognitive therapists are somewhat confused by the term “Socratic questioning” and so has devised a sheet by which to instruct therapists (see Appendix 1.C, p. 45). The most important Socratic questions for clients to memorise are the ones printed at the bottom of the example DTR (see Appendix 1.A, p. 43): What’s the evidence for and against my AT/image? What are other ways of looking at this situation? What’s the worst that could happen in this situation and could I survive it? What’s the most likely to happen? What’s the effect of my believing my AT? What constructive action could I take to make things better? Therapists also use Socratic questioning in performing the downward arrow exercise to determine the underlying meaning to the client of prior ATs if they were true (for example, What would it mean if I did fail the test? What would this mean?, etc.) (Burns, 1980; see also Figures 5.2 and 5.4). The dysfunctional thought record (DTR) One of the prime tools for therapists and clients to have at their disposal is the DTR. This sheet enables clients to more easily dissect their problematic experiences and examine how adaptive and/or accurate certain examples of their thinking are. An example of this filled in with actual responses from a client is found in Appendix 1.A (p. 41). Note that the more common, useful Socratic questions are found at the bottom of the page to help the client formulate more adaptive responses. A therapist might introduce the DTR to the client thus: I have a form here which helps us tease apart the different parts of distressing situations you encounter. By clarifying these different aspects – emotions, thoughts, the situation itself – we can see more easily how your current way of interpreting situations contributes to your distress. We can also help you see the same situation more objectively and adaptively. This way you can explore other ways of interpreting the situation Cognitive treatment of depression 25 that are not so painful or disruptive for you. By practising these new ways of looking at things (including yourself and your own behaviour) there’s a very good chance that you’ll feel a great deal better. How about if we take a look at it now? Some of the snags that can occur in teaching the DTR to clients are detailed next. The author has found that clients especially tend to make these mistakes: 1 2 3 Putting interpretations of the situation (which really belong in the AT column) in the Situation column. For example, “Steve arrives late to the party, as always.” Correct would be: Situation: “Steve arrives 15 minutes late to the party.” AT: “He always arrives late.”). Not understanding the difference between thoughts/images and feelings. This is especially common when the client uses the phrase, “I feel that . . .” followed by an interpretation of the situation rather than following the “feel” word with an actual emotion word as in, “I feel sad.” It can help to provide the client with a visual list of one-word feelings at these points. Usually saying something like the following can help clarify these points in the client’s mind: “OK, you thought that you were a bad parent. We’ll put that belief in the AT column. And how did that thought make you feel? Embarrassed, annoyed, guilty, pleased, sad?” Occasionally clients will also put words really indicative of interpretations in the emotion column. For example, a client may put “rejected” in the emotion column, but this really implies an action by someone else. The emotion accompanying this perceived rejection (“sad” or “lonely”) would go in the emotion column, whereas the “rejection” would go in the AT column. Misunderstanding the exact intention of the reasonable adaptive response (RAR) column. In many cases I have seen clients write something in that column that does help them feel better temporarily, but is irrelevant to the AT or image that is causing them to feel distressed. Example: A client had written as her AT, “I have no friends.” She believed this strongly and it made her sad. For her response she had written, “Well, at least my mom loves me.” This did briefly improve her mood. It did not, however, directly address either the original AT or any assumptions underlying this (for example, If I currently have no friends, I never will. If I currently have no friends, it means I’m deeply flawed. If I currently have no friends, it must be all my fault. I am unlovable). For this reason it was a poor response to her AT and led only to very temporary relief rather than helping her to view herself and the world more accurately and adaptively. Only this deeper type of cognitive reorientation would likely lead to lasting change. 26 Kevin T. Kuehlwein In addition, therapists sometimes make the mistake of teaching the DTR to a client all at once and thus overwhelming the client. Instead, it is often a better idea for the therapist and client together to partially fill out the DTR with the client’s own example, simply inserting data in the first three columns and leaving the RAR column blank, since this is the hardest column to complete. The RAR column can be addressed in the next session after the client has better understood the structure of the sheet. Repetition of nascent positive beliefs Whenever a client comes up with an at least moderately persuasive functional belief that represents an alternative to a more depressive belief the therapist seeks to reinforce this nascent cognition by repetition in the client’s mind. Many clients are persuaded by their old negative beliefs largely because they or others have incessantly repeated these or related cognitions. Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda, is said to have claimed, “If you repeat a lie often enough, the people will believe it.” Therefore clients typically need to self-consciously support new, somewhat weaker beliefs that are more functional via similar repetition. Coping cards represent one such way. In this approach a client transcribes onto 3 inch by 5 inch cards (preferably coloured for added emphasis) new more adaptive beliefs she seeks to strengthen. She then carries them with her, reading them many times during the day. She may also want to post them in prominent places at home or work where she would read them often. She could augment the effectiveness of this technique by actively searching for examples of the new belief (for example, “I am at least as competent as most people”) in her daily life and writing these down with sufficient details that will help her recall them later. Indeed, she can amass weekly examples of such new beliefs on a running list (for example, an adequacy log) so that the impact of these may accrete over time and provide a persuasive antidote to lingering fears of the truth of the old belief. Revising core beliefs As the therapy progresses, deeper, more central beliefs will surface. Sometimes a client may successfully address these by using the DTR. More often, however, other methods may need to be used. One of these is a sheet similar to Revising Core Beliefs (see Appendix 1.D, p. 47). This tool measures the strength of old, dysfunctional beliefs as well as newer, more functional ones. Its most important use, however, is in eliciting so-called evidence that the client has maladaptively used to support dysfunctional deeper beliefs (for example, I am worthless) currently or in the past. The therapist and client write in the first column data allegedly supporting the negative core belief (for example, I was given away at birth by my birth mother). The second column examines this often poor quality “evidence” and attempts to undermine it by Cognitive treatment of depression 27 exploring other plausible explanations for the same data (for example, She couldn’t care for me and wanted me to have a better chance in a better family situation. She likely felt a lot of conflicts about the adoption). The final column attempts to elicit several various data that are supportive of the new core belief that conflicts with the old core belief (for example, I have several good friends who treat me well and am dating a good man who shows me respect and care). Finally, the bottom portion serves as a place for the client to fill in possible activities she could engage in during the next week that would lead to further experiences supporting the new core belief. This sheet is typically begun in-session and the client is sent home to continue it after entering several examples in each column. Completing several such sheets on each of the client’s major negative core beliefs over time often greatly reduces the client’s belief in damaging cognitions and builds up confidence in the more adaptive core beliefs. As above, clients should ideally strengthen these new beliefs by carrying written copies of them around on coping cards that they refer to several times per day. Rational–emotional role plays Frequently clients will complain that they know the new adaptive beliefs are accurate, but that the old beliefs still feel more accurate. They may phrase the idea somewhat differently: “I don’t believe it in my gut yet.” The rational–emotional role play is often the ideal cognitive intervention for such clients. This experience (largely imported from gestalt therapy) distils the two sides of internal struggle and pits them against each other in a very evocative (and thus memorable) way. The client begins by identifying two opposing beliefs, one emotionally persuasive and maladaptive and the other at least somewhat intellectually persuasive and more desirable. The client then occupies another chair facing her original one and speaks to her now absent self to convince herself that the old core belief (for example, “I’m incompetent”) is correct. The therapist actively encourages the client to verbalise literally all the data used over the years to support her old core belief. In this way both therapist and client can ascertain which data need to be reframed in more positive ways. In the next phase the client returns to her original chair and – with prompting and/or modelling, if necessary – rebuts the alleged evidence previously offered by her more critical side. The therapist encourages the client vehemently and firmly to challenge the relevance of such data and instead develops other, more plausible and balanced interpretations of these same data. Once the therapist is satisfied that the client has explored this second side fully, he checks for a reduction in belief level in the old core belief and in the accompanying distress. If it does not occur, the exercise may be repeated. Again, the client writes down key points emerging from this role play so that she may review and repeat these to herself over the next few weeks as a way of strengthening them. 28 Kevin T. Kuehlwein Point–counterpoint A certain subset of depressed clients temporarily benefit from cognitive restructuring, but derail this almost reflexively by an opposing, negative AT that counters the more adaptive thought. It is as if the client had said, “OK, that [new belief] may be technically true, but it doesn’t count because . . .” Clearly the client at this point is having a secondary, disqualifying AT that needs to be addressed and evaluated. Point–counterpoint is a technique that has been successfully employed to parry these latter types of thoughts. In this technique the client draws a vertical line down the middle of a sheet of paper, labelling one column ATs and RARs. She then writes her first AT and in the next column a good RAR that specifically examines and modifies this AT. Moving back to the first column, she enters the disqualifying AT that makes her doubt or minimise the prior RAR, but she does not stop there. Instead she continues to evaluate and modify this AT by developing and writing a RAR to counter this, repeating this process as long as necessary. The only rule is that the client must end in the RAR column. The client therefore never lets her minimising AT stand without challenge. In this fashion the client can gradually wear down any resistance she may have to accepting her more reasonable responses by repetition and not shying away from a fair examination of the supposed evidence that disqualifies the original RAR. This can also be done out loud in an evocative role play whereby the client rotates between chairs (see also the similar rational–emotional role play exercise described in the preceding section) as she states her objections to the RAR and then calmly answers these in turn. Visualisation Depressed clients often suffer from a paucity of healthy imagination. By that I mean that it is hard for them to see themselves, the world around them, and the future with any fullness and clarity. Instead they see a very stereotypically reduced image of things, all phenomena basically having a negative cast. This biased perception naturally makes it harder to emerge fully from the chrysalis of depression for it forestalls much adaptive action, emotion, and thought. It is for this reason that helping clients to visualise better (i.e., more accurately and adaptively) can be an important part of helping them move out of depression. Many therapists make the mistake of not probing adequately for automatic thoughts that occur in imagined form, but this is often a large mistake. One of the peculiar things about having images is that these internal pictures can seem especially convincing to clients because they have in some sense actually seen their fears being realised or have gone back in time when a terrible real event from the past occurred and are reliving it, if only for an instant. Although these cinematic realities occur only within the client’s own head, they can still be powerful impediments to feeling, thinking, and Cognitive treatment of depression 29 acting more adaptively. Frequently when clients report dysfunctional images the best way for them to counter these is by replacing them with a more accurate and/or adaptive mental image, rather than with a simple, one-dimensional verbal reasonable adaptive response. Layden (Layden, Newman, Freeman, & Morse, 1993) has written of the integral part of visualisation in assisting clients out of distress. As part of a process designed to help clients move toward their future goals, she recommends therapists work with clients to actively foster positive, attainable images of their not-too-distant future (for example, six months to several years from the present), thus building an evolving, adaptive mental representation of one’s future toward which to strive during the course of therapy. This not only helps clients to rehearse more salubrious mental scenarios, it often lifts depressed affect as clients experience a momentary escape into a more positive future. The sparks of hope that are nurtured at home as clients practise seeing in ever-increasing and multi-sensorial detail key aspects of their future life can provide some of the warming growth toward realising (in both senses of the word) these more positive potential future outcomes. Visualisation is also useful in combating those often potent ATs that occur in the form of images. The most effective challenge to an imaginal AT is usually a different, more balanced and realistic image, so the therapist encourages the client with a distressing image to transform it to a more realistic one and ensures that she has successfully done so by checking to see how much the client’s distress level reduces at the end of the exercise. Readers especially interested in the application of imagery to cognitive therapy should also see Edwards (1989). Continuum method In working with depressed clients therapists often encounter a great deal of all or nothing thinking, itself one of the main cognitive distortions that help to maintain a client’s depression. It is therefore important to be able to counter this distortion by means of the continuum method. In this case, the therapist elicits a key example of all/nothing thinking (that is, one that causes the client a great deal of distress instead of one that is more peripheral) and explores with the client the construct in question by means of Socratic questioning. A reconstructed example (based on a real client of the author) follows: Th: What problems should we work on today, Linda? L: I don’t know. I just feel awful today. I am such a bad mother. I am really ashamed. Th: Wow. You sure sound and look as if you feel pretty awful. Just slow down a little and tell me what happened to make you so ashamed and feel like such a bad mother. L: I completely screwed up last week and ruined my daughter’s birthday. 30 Kevin T. Kuehlwein Th: Hmm. Can you tell me what you mean by “completely screwed up”? L: I just completely forgot about it! Can you imagine: forgetting your own daughter’s birthday! God! What kind of mother does that? Th: That does sound upsetting. Can we explore the specifics of this, though, Linda? I want to make sure I understand everything so I can help you answer that very question you just posed. Let me draw something here so we can look at this more closely [goes to whiteboard and draws a long continuum, with one side marked GOOD (0% bad) and the other marked BAD (100% bad)]. Now where would you put yourself on this scale from 0 to 100 with 0 being the best mother in the world and 100 being the worst mother in the world? L: 90%. Th: OK. And what makes you say 90%? L: Because it’s a really terrible thing to forget a child’s birthday. Th: You’re right in the sense that children’s birthdays are pretty important to them. Let’s get a sense of where you’d put some other mothers on this scale first before we look more at that. Let’s think of somebody who’s really a terrible mother – somebody right at the end of this. What would she do as far as parenting? L: Well I guess she’d be mean to them a lot, yell at them, probably not clothe them very well and generally criticise them all the time. Th: So that would be 100 on this scale? That’s the worst that you can think of? L: Yeah, I guess. Th: Well, that sounds mean in some ways, but I wonder if you’ve heard of an even worse mother? What about if a mother were to not only criticise her kids all the time, but actually physically sexually abuse them, sell them into slavery, kill them, or who actually takes pleasure in their suffering? Where would that type of mother go on the scale? L: Oh, my god! That would definitely be a 100. Th: OK. Yeah, that does sound worse than what you came up with, doesn’t it? So, if that person would be 100, where do you belong on this scale? Still at 90 or have you moved up or down? L: Well, I guess what I did wasn’t that close to somebody who really abuses their children like that. Th: What makes you say that? How is what you do different? L: Well, I’m not hurting her on purpose. Th: Excellent point. What was Suzie’s actual reaction to everything, by the way? We didn’t find out how she actually felt about things. L: She had a great time. She was running around in that new outfit I got her and was having fun playing a party game with her friends from the neighbourhood. Th: That’s interesting. So although you’re a supposedly bad mother, it doesn’t seem as if your awful mothering produced any negative effects in the person you supposedly offended. What do you make of that? Cognitive treatment of depression L: Th: L: Th: L: Th: L: Th: L: Th: L: Th: L: Th: L: Th: L: 31 I guess I never thought of that. But isn’t it still a terrible thing to forget your child’s birthday? Linda, I’m struck with how you keep using the term “forget” as if you completely forgot and only remembered 4 weeks later and then chose to do nothing to rectify your error. Let’s investigate that question you just put to me by going back to this continuum: How terrible is forgetting a child’s birthday in the overall scheme of things? It’s bad, but I guess it’s not so bad. OK and – getting back to the bad mother part – if you were a really bad mother – completely bad – what would we expect your reaction to be to forgetting your daughter’s birthday? Hmm. [thinking] I guess if I were a really awful mom I wouldn’t care at all if I forgot it because it wouldn’t mean anything to me. If I were a really terrible mom, I’d probably make fun of her just like any other day. Right. Now, how close was that to what you actually did when, like most of us humans, you forgot something that you didn’t want to forget? Well, I guess it wasn’t very close. I did try to make up for what I did. OK and how much does that count: that you didn’t intentionally forget or try to hurt her, you’d already bought her gifts, you made sure she had a good time as soon as you remembered, and that she didn’t feel hurt at all? How do those stack up against your having initially forgotten her birthday? I guess those are really more important. Seems so, doesn’t it. What we’re doing is looking at the larger picture, seeing your action in context. But we also want to take a look at this to see if there’s a pattern here. How often do you condemn yourself so quickly and completely with issues like this and minimise positive things you do? Pretty often, I guess. And what do you suppose is the cumulative effect of that over time? It probably makes me feel bad a lot. Yeah, that would be my guess. What do you think would be the effect over time of your realising that you’re human, too, and therefore entitled to make the occasional harmless mistake? I guess I’d probably like myself better. [brightening] I think you really would. So let’s look to see if that happens and let’s be careful about those cognitive distortions we uncovered [circles them on a sheet he hands to client]: all or nothing thinking, labelling, disqualifying the positive, OK? OK [smiling]. Behavioural experiment This refers to the prospective gathering of data by the client to investigate a belief she has verbalised (for example, no one will say hello to me today even 32 Kevin T. Kuehlwein if I say hello to them). Client and therapist together specify clearly the idea to be tested and determine criteria that would indicate evidence for and against this theory. Next they determine a scenario in which the client could impartially test the theory and the client goes out and collects data in response to her prescribed action (for example, saying hello warmly and smiling to 10 people in varying situations). The data are then recorded and discussed at the next meeting. Many times the client’s predictions are incorrect, which is often surprising for the client. This exercise can provide useful support for other, more adaptive beliefs. The surprise experienced by the client often punctuates and intensifies the new learning. When the data do support her theory, therapist and client try to determine what circumstances (for example, the client’s own actions) might have contributed to this. Problem-solving approaches to develop a new approach to the situation are then explored. Completing the feedback loop Another helpful cognitive intervention is what the author refers to as completing the feedback loop. It is quite intriguing to notice how often our clients (and indeed, we, ourselves) engage in the following dysfunctional and illogical pattern: (1) having an idea about something (for example, I’ll do terribly on my exam); (2) encountering a situation in which the client could test this (for example, actually sitting for an exam); (3) having the situation turn out differently than expected (for example, passing or doing well on the exam) and then not using this discrepant and important information to go back and correct our faulty beliefs. Many times clients continue this process with the same dysfunctional belief numerous times as if for the first time. It is as though the contradictory data simply vanish. Part of the reason this disappearance of data occurs is that the depressed client does not have a readily accessible more positive template (for example, “I am competent at many things”) in which to fit more positive experiences (McKay & Fanning, 1991). Therefore contradictory information either is forgotten quickly or is simply not stored in any permanent form at all. Good therapists therefore know the importance of keeping clients’ attention focused on personal outcomes that run counter to their dysfunctional beliefs. Observant readers will note how this is almost a naturalistic post-hoc behavioural experiment. Practical problem-solving Clients need to know very clearly that cognitive therapy acknowledges that there are real problems in their lives; it is not all in the way they look at things. At the same time cognitive therapy posits that many of depressed clients’ typical cognitions (for example, “There’s nothing I can do” or “I’m not smart enough” or “This is too overwhelming!”) significantly interfere with or even exacerbate the solution of these problems. Such beliefs not only Cognitive treatment of depression 33 interfere with solving current problems, but also shroud their past successes in darkness so that the client cannot see them clearly and draw inspiration and encouragement from them. So cognitive therapy naturally focuses first on removing this extra layer of impediments to the problem-solving process and then moves on to generating possible solutions. It does this by treating the beliefs again as theories that need to be examined and tested. The therapist then teaches the client the following steps: identify the problem with precision, devise a range of possible solutions (without judging or censoring any), evaluate the different possible solutions in terms of their strengths, select a solution, implement this, and judge its effectiveness in solving the problem. The process may be repeated if the first solution does not yield the desired results. The problem-solving model is explained in more detail elsewhere (D’Zurilla, 1986). Addressing suicidality It is critical to address suicidal thoughts, feelings, and behaviours with depressed individuals. Depression is very demoralising and the hopelessness that derives from the pervasive negative views of self, future, and ongoing experience can predispose a client to consider drastic measures (including suicide) to stop their suffering. For this reason it is paramount to enquire regularly about thoughts of self-harm and hopelessness, the latter of which has been linked to increased suicidal risk (Beck, Steer, Kovacs, & Garrison, 1985). Asking at the beginning of each session either verbally or on pre-session forms (for example, the BHS and BDI) can help to elicit such thoughts and feelings. Questions 2 and 9 on the BDI are the most highly associated with suicidality, number 2 even more so than number 9 because it taps a client’s hopelessness. Likewise a score of 9 or higher on the BHS alerts the therapist to increased risk of suicidal action. Because of the acute nature of suicidality, it must always be the highest priority on the agenda when suicidal thoughts are anything more than fleeting. A common mistake some clinicians make at this stage is to try to elicit from the client or present reasons to the client why suicide is not a good option. It is important to realise, however, that the client, already struggling with a great deal of pain, may consider this approach to be further invalidation of her pain and problems. Rarely has a client quickly jumped to the idea that suicide is a good option. Rather most clients arrive at this option only after many other attempts to solve their problems. It is therefore very important for the clinician dealing with a suicidal client to elicit the client’s reasons both for and against this drastic option. This ensures that both of the client’s important perspectives are heard and understood. After exploring the reasons for suicide the therapist can have a better understanding of how best to elicit and/or provide alternative methods for reaching the functional goals underlying the option of suicide (typically 34 Kevin T. Kuehlwein cessation of pain). By eliciting these goals the therapist can empathise with the client while at the same time offering an alternative perspective on how appropriate the suicide option is for achieving them. Recall that persons who are depressed often suffer from a narrow imagination. Therefore, their problem-solving skills are currently depressed as well (see earlier section on this). Eliciting goals and exploring options in terms of problem-solving can therefore help a client feel empowered and as if somebody really understands the depths of their misery. Eliciting and listing on paper numerous positive reasons for living (for example, I want to see my son graduate from college or I don’t want to hurt my family) can also help tip the scales of doubt toward living (Beck et al., 1979; Ellis & Newman, 1996). Many clients who suffer from chronic suicidality (and, indeed, their therapists) may benefit from reading and working through the exercises in the Ellis and Newman (1996) book, which takes a cognitive therapy approach to the issue of suicidality. This subject has been only cursorily explored here because it is discussed in full detail in Freeman and Jackson (Chapter 2, this volume). Nurturing the therapeutic relationship Some therapists have underappreciated the importance of the therapeutic relationship. Yet it is crucial to the success of cognitive therapy for the therapist to carefully nurture the therapy alliance and pay attention to any ruptures within this. Careful management of situations where the client is disappointed in the therapy, the therapist, or the client’s own role in the therapy often leads to resolutions of impasses, including enhancement of the therapeutic relationship and even therapeutic breakthroughs. One of the best ways to assess the strength of the therapeutic relationship is also the simplest: simply asking clients in an open way about their reactions to the session or the therapy as a whole so far. In training therapists the author has found that many therapists too often ask feedback questions in ways that are ironically less likely to elicit what the client truly feels and thinks. They do this by framing the questions in all or nothing fashion: “Was the session helpful today?”, for example, at the end of the session. When a therapist who has been friendly asks such a question, it can be especially hard for the average client honestly to admit when it largely has not been. The therapist here also models the wrong type of thinking (all or nothing) for the client. Many times there are a variety of feelings and thoughts the client has about the therapy, not all of them completely positive. Yet, if the therapist presents the feedback in a yes/no fashion, many clients are unlikely to step out of this framework and provide this more mixed feedback. For this reason the author suggests that the therapist ask as many questions during the therapy in the form of openended or continuum-like questions: “Tell me what you got out of today’s session.” or “To what extent did you feel heard or understood today?” “What do you like best about therapy?” “What do like least?” “What things would Cognitive treatment of depression 35 you change about how we work if you could?” Notice how these latter questions encourage much greater thought and require more in the way of a reply from the client. Note also how a vague answer to the former question can provide key feedback for the therapist to revise his approach to the client so as to increase client retention in the future. As with other aspects of the therapy the therapist must use his conceptualisation to structure the relationship with each client. This helps him to ensure that his interventions flow from his best understanding of what the client needs to participate optimally in the therapy process. One must be careful not to repeat patterns with clients that helped predispose them to being depressed in the first place. Beware, for example, of doing too much of the therapy work for a client who presents with a helpless core belief. In spite of how obvious this sounds when written down, it is surprising how often therapists slip into this pattern in their desire to help clients escape their suffering more quickly. It is, however, a trap to do too much of the work for a client who is capable of doing it herself. Rather this pattern needs to be explored in a sensitive, supportive way with such clients. Client non-compliance The author cannot credibly maintain that most depressed cognitive therapy clients delight in all aspects of the therapeutic process and perform their recommended homework tasks with relish. The nature of depression as well as characteristics of therapy militate against this. While certain aspects of cognitive therapy (collaboration and presentation of rationales for interventions) probably help decrease non-compliance tendencies, there are still many times in therapy when clients do not comply. With these clients the author recommends stepping back from the problem and seeking to understand – true to the concept of conceptualisation – the nature of the problem. When the client is reluctant to perform a particular task that seems important in the therapist’s mind for progress in therapy, it is always good to ask questions of the client to better understand what the obstacle is. The client’s first stated reasons may not necessarily always be the most accurate ones. Good questions here in the example of the client not writing thoughts down could include the following: “How close did you get to completing the assignment? Did you go so far as to take out the sheet and a pen? What thoughts went through your mind as you thought about doing the assignment? How helpful did you believe writing down your thoughts would be? What did you think would happen if you did write down your thoughts?” In this way the therapist could distinguish social embarrassment ATs (for example, My neighbour might see it when she comes in for coffee and I’d be embarrassed) from hopeless ATs (Nothing’s going to help, so why should I bother?). Each of these suggests a different response from the therapist. A good additional resource for the therapist here is the Possible Reasons for Not Doing 36 Kevin T. Kuehlwein Homework Assignments Sheet (Beck et al., 1979). This sheet can help therapist and client understand the myriad interfering cognitions that may impede therapy progress. These cognitions can then be examined more carefully as a way of weakening their grip on the client so that the client can at least experiment with doing the avoided assignment to see what actual result occurs. Since non-compliance does not occur in a vacuum but is the product of an interpersonal situation, the therapist also should explore the extent to which his attitudes and actions play a role in any non-compliance. Keep in mind also that any non-compliance can inform the therapist’s conceptualisation of the client (Newman, 1994). Relapse prevention Toward the end of therapy when clients have successfully reduced their deeper negative patterns of belief, affect, and behaviour, the therapist’s attention turns to reinforcing the patterns of client change. In this last phase of treatment the therapist and client review client gains and seek to identify future problem scenarios so that the client does not leave therapy falsely believing herself to be invulnerable. Rather, the therapist inculcates in the client a belief that she now has a set of effective tools to use across the problem areas of her life as well as a high degree of competence in applying and knowing when to apply these tools. For this reason the last few sessions involve the therapist and client revisiting earlier deeper dysfunctional beliefs and situations so as to assess how confident the client would be in facing related situations evoking such types of thinking in her. Client and therapist list scenarios most likely to lead to a resurgence of depression and develop brief plans for dealing with these based on therapy successes. Clients can be taught to visualise in session such trigger situations occurring, becoming initially upset, and then applying the most relevant coping skills (for example, their most effective new, adaptive beliefs) so as to reduce their distress. More depth on this topic is offered in Beck (1995). External adjuncts to therapy: self-help groups and computer resources Recently clients have increasing access to a plethora of quasi-therapy groups and resources outside the confines of therapy, most of which are descendants of 12-Step fellowships like Alcoholics Anonymous. Many of these can be excellent adjuncts to therapy because clients often reinforce their knowledge of themselves and the impact of their dysfunctional belief systems. Such clients may also interact with others who share issues with them and thereby learn from them how to cope successfully with common problems and issues. Because fellow group members often suffer or have suffered from depression (which the therapist may or may not have done), clients exposed to such Cognitive treatment of depression 37 people may more likely integrate certain new perspectives from therapy. The author recommends strongly that clients who attend such groups periodically share information about what is occurring in them and what their reactions are to such discussions. In this way therapist and client can take optimum advantage of opportunities to reinforce messages that will ultimately be helpful to the client or opportunities to clarify points of difference. Cyberspace offers other potentially useful resources to those with computers and modems. Although not all resources are equally helpful, therapists should be aware of them and their potential impact (positive and/or negative) on clients. Clients may, for example, participate directly in on-line discussion groups run by people struggling with similar problems. They may also be strongly affected by information promulgated by groups and persons who are a “virtual” presence on the Internet, computer bulletin boards, or on-line service companies (for example, America OnLine). There are now support and advocacy groups for mental health concerns that discuss knowledgeably such subjects as treatment options, efficacy of certain treatments (psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, as well as other, less well-established approaches). There are also forums that take place in cyberspace at regularly scheduled times, where a sense of community may build differently than in a newsgroup section where people talk and respond in more piecemeal fashion. Many of these groups never meet face-to-face. Rather they are more “virtual” communities in that they consist of people connected via computers and modems, but it would be a mistake to underestimate the importance or potential of such groups in providing support and knowledge to depressed individuals. Ideally, such groups and individuals provide accurate information about therapy modalities and medications, but in today’s world there are unfortunately no assurances and misinformation can also spread quickly in this fashion. Therefore the author recommends that therapists with clients likely to have access to these resources should clarify the range of what is available and give clients a sense both of what dangers and benefits exist on-line. In general clients receive more consistent and accurate information from well-established groups without a particular bias to them (for example, pharmaceutical companies who may push all pharmacological options above psychotherapeutic ones). A good first site to direct clients to is the American Psychological Association homepage (http://www.apa.org on the World Wide Web). If clients do use Internet or other on-line resources, the therapist should strongly encourage them to discuss their experiences, so that the therapist can be aware of other possible influences (both helpful and unhelpful) on a client’s progress during therapy. Concluding thoughts and recommendations The ideas presented here have given a summary of some useful approaches within the powerful cognitive model to utilise with depressed clients. 38 Kevin T. Kuehlwein However, given that clients often come in to therapy after weeks, months, or years of suffering depression, it is important to recall that many clients’ entrenched negative patterns can crowd out more adaptive patterns. It is therefore sometimes difficult for them to maintain positive, alternative perspectives on their situations. For this reason therapists frequently find that they need to provide the client with concrete reinforcement of the client’s own new ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving. Some common ways to accomplish this are as follows: audiotaping each session and encouraging the client to listen to the session later, when they may be better able to hear and consolidate the many messages communicated within the earlier session. Another good approach is for the client to take written notes during the session and to review these later. Given that most of the content of a therapy session is forgotten later, these methods can greatly help clients to recall and then integrate important learning from therapy in their daily life. In general, the more clients think about the therapy outside, the greater the likelihood that they will be modifying their thinking, behaviour, and feelings. Therapists should also help clients to visually represent both old problematic patterns and newer, more functional ones. The author uses a “whiteboard” and coloured erasable markers to demonstrate graphically certain points during the session. Clients then copy these down on paper so that they will have a copy to refer to later. Relationships between certain phenomena within the client’s life are often easier to understand when they are represented graphically or are at least greatly aided by additional graphical representation (see Appendix 1.E, p. 48). Utilisation of these approaches can assist the therapist in strengthening the newer patterns elicited and explored in the sessions so that durable change from therapy can occur. References Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (1993a). Depression in Primary Care: Treatment of Major Depression (vol. 2; AHCPR publication 93-0551). Silver Spring, MD: Author. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (1993b). Depression in Primary Care: Diagnosis and Treatment (Quick Reference Guide for Clinicians; AHCPR publication 93-0552). Silver Spring, MD: Author. American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author. Beck, A. T. (1978). Depression Inventory. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Cognitive Therapy. Beck, A. T. (1993). Cognitive therapy: Past, present, and future. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 6, 194–198. Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 893–897. Beck, A. T. & Greenberg, R. L. (1974). Coping with Depression. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Cognitive Therapy. Cognitive treatment of depression 39 Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford. Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Kovacs, M., & Garrison, B. (1985). Hopelessness and eventual suicide: A 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 559–563. Beck, A. T., Weissman, A., Lester, D., & Trexler, L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 861–865. Beck, J. S. (1995). Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York: Guilford. Bourne, E. J. (1995). The Anxiety and Phobia Workbook, revised 2nd ed. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger. Boyd, J. H. & Weissman, M. M. (1981). Epidemiology of affective disorders: Reexamination and future direction. Archives of General Psychiatry, 38, 1039–1046. Burns, D. D. (1980). Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. New York: New American Library. Burns, D. D. (1989). The Feeling Good Handbook. New York: New American Library. Cassem, E. H. (1988). Depression secondary to medical illness. In A. J. Frances & R. E. Hales (Eds.), Review of Psychiatry, vol. 7, pp. 256–273. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Center for Cognitive Therapy (1993). Patient’s Guide to Cognitive Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Author. DiGiuseppe, R. (1993). Comprehensive cognitive-behaviour therapy with a socially isolated child. In K. Kuehlwein & H. Rosen (Eds.), Cognitive Therapies in Action: Evolving Innovative Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. D’Zurilla, T. J. (1986). Problem-solving Therapy: A Social Competence Approach to Clinical Intervention. New York: Springer. Edwards, D. J. A. (1989). Cognitive restructuring through guided imagery: Lessons from gestalt therapy. In A. Freeman, K. M. Simon, L. E. Beutler, & H. Arkowitz (Eds.), Comprehensive Handbook of Cognitive Therapy. New York: Plenum. Ellis, T. & Newman, C. F. (1996). Choosing to Live: How to Defeat Suicide through Cognitive Therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger. Fennell, M. (1989). Depression. In K. Hawton, P. M. Salkovskis, J. Kirk, & D. M. Clark (Eds.), Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Psychiatric Problems: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Freeman, A., Schrodt, G. R., Gilson, M., & Ludgate, J. W. (1993). Group cognitive therapy with inpatients. In J. H. Wright, M. E. Thase, A.T. Beck, & J. W. Ludgate (Eds.), Cognitive Therapy with Inpatients: Developing a Cognitive Milieu. New York: Guilford Press. Hays, R. D., Wells, K. B., Sherbourne, C. D., Rogers, W., & Spritzer, K. (1995). Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 11–19. Hirschfeld, R. M. A., Keller, M. B., Panico, S. et al. (1997). The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association Consensus Statement on the Undertreatment of Depression. Journal of the American Medical Association, 277, 333–340. Hollon, S. D. (1996). The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy relative to medications. American Psychologist, 51, 1025–1030. Hollon, S. D. & Beck, A. T. (1994). Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies. In A. 40 Kevin T. Kuehlwein E. Bergin & S. L. Garfield (Eds.), Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 4th ed., pp. 428–466. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Hollon, S. D. & Shaw, B. F. (1979). Group cognitive therapy for depressed patients. In A. T. Beck, A. J. Rush, B. F. Shaw, & G. Emery, Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press. Jonsson, B. & Bebbington P. E. (1994). What price depression? The cost of depression and the cost-effectiveness of pharmacological treatment. British Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 665–673. Kind, P. & Sorenson, J. (1995). Modelling the cost-effectiveness of the prophylactic use of SSRIs in the treatment of depression. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 10 Suppl.1, 41–48. Kurtz, E. & Ketcham, K. (1992). The Spirituality of Imperfection: Storytelling and the Journey to Wholeness. New York: Bantam. Layden, M. A. (1997). Formula Sheet. Unpublished manuscript. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Cognitive Therapy. Layden, M. A., Newman, C. F., Freeman, A., & Morse, S. B. (1993). Cognitive Therapy of Borderline Personality Disorder. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. McKay, M. & Fanning, P. (1991). Prisoners of Belief. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger. McKay, M. & Fanning, P. (1992). Self-Esteem, 2nd ed. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger. McMullin, R. E. (1986). Handbook of Cognitive Therapy Techniques. New York: W. W. Norton. Newman, C. F. (1994). Understanding client resistance: Methods for enhancing motivation to change. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 1, 47–69. Overholser, J. C. (1993a). Elements of the Socratic method: II. Inductive reasoning. Psychotherapy, 30, 75–85. Overholser, J. C. (1993b). Elements of the Socratic method: I. Systematic questioning. Psychotherapy, 30, 67–74. Persons, J. (1993). Case conceptualization in cognitive-behavior therapy. In K. T. Kuehlwein & H. Rosen (Eds.), Cognitive Therapies in Action: Evolving Innovative Practice, pp. 33–53. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Persons, J. B. (1989). Cognitive Therapy in Practice: A Case Formulation Approach. New York: Norton. Persons, J. B., Burns, D. D., & Perloff, J. H. (1988). Predictors of dropout and outcome in cognitive therapy for depression in a private practice setting. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 12, 557–575. Safran, J.D. & Segal, Z.V. (1990). Interpersonal Processes in Cognitive Therapy. New York: Basic Books. Safran, J. D., Vallis, T. M., Segal, Z. V., & Shaw, B. F. (1986). Assessment of core cognitive processes in cognitive therapy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 10, 509–526. Santrock, J. W., Minnett, A. M., & Campbell, B. D. (1994). The Authoritative Guide to Self-help Books. New York: Guilford. Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J.B.W., Gibbon, M., & First, M.B. (1990). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Wright, J. H. (1988). Cognitive therapy of depression. In A. J. Frances & R. E. Hales (Eds.), Review of Psychiatry, Vol. 7, pp. 554–570. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Situation: Briefly jot down a few details about what you were doing (including stream of thought), where you were, and/or who you were with when you felt your mood drop. Example: Sitting home alone thinking about test tomorrow. Emotion: Use a word or two to describe your FEELINGS at the time (e.g., sad, embarrassed, angry). Then rate how strongly you felt these emotions (5% [very little] to 100% [the most I have ever felt this emotion]). Put low, medium, or high if unsure. Automatic thought/image: Put down here what was going through your mind when you felt upset.Try to capture it in the same words or images that you hear or see, even if they sound extreme or even silly to you.Then rate how strongly you believe the thought or image (5% [not much at all] to 100% [I completely believe it]). Or just put low, medium, high if it’s hard to quantify. Reasonable adaptive response: Take a step back from your thought/ image and the situation (using the questions at the bottom of the sheet) and try to evaluate your thought/ image in terms of how accurate and/or helpful it is for you to look at things in only this way. (You may also want to see if you can recognise any types of “cognitive distortions” that may be lurking in the AT/image.) Now go back to the % in the last column. If it has changed (up or down), then cross out the old %age and put in the new %age behind it. Do the same for the emotions. NOTE: If you don’t have this sheet with you at the time, jot down enough details about it on some piece of paper so you can fill out this sheet later more completely. Instructions: Take note of when your mood drops (typically a sign that some sort of dysfunctional thought/image is being triggered and believed). When you feel the distress, write down the following: a brief description of the situation you’re in, your emotions, the thoughts/images that accompany the emotions, and then see what alternative responses you can generate to your thoughts/images and/or the situation. Cognitive treatment of depression Appendix 1.A. Sample completed Dysfunctional Thought Record 41 Had a conversation with my mother about my father. She described him as self-absorbed, unable to have a conversation and isolated. 50% 50% (Additional later emotion: Relief 40%) Scared (20% later) Depressed (20% later) I’m going to end up like my father: self-absorbed, few friends, isolated, depressed 90% (20% later) Disqualifying the positive: I am overlooking the fact that I have positive qualities: 1) I admit that I have a problem with self-esteem and I’m getting help. 80% 2) I’ve made major progress in my relationship with my daughter. 80% 3) I am less shy than I used to be. 75% 4) I have more confidence than I used to. 65% 5) I am much less anxious than I was X years ago. 90% 6) I have friends that I can be honest with: husband, B., C. [to some extent], R., & W. 65% 7) I am depressed less often and with less severity than before. 90% All or nothing: If I’m not like my mother it doesn’t follow that I am like my father. I can be unique, not a copy of either or both. 75% Overgeneralization: Just because I’m similar to him in some ways, doesn’t mean I am totally like him. 75% Fortune telling: How do I know that? 60% 42 Kevin T. Kuehlwein Appendix 1.A. Cont. Questions: 1a. What’s the evidence for and against my AT/image? 1b. How persuasive would this evidence be to others? 2a.What’s another way of looking at the situation or the evidence? 2b. If a friend were in this situation and had this thought, what would I say to him/her? 3a.What’s the worst that could happen here? 3b.What’s the best? 3c.What’s the most reasonable to expect? 4.What constructive action could I take to improve my situation? 5a. What’s the effect (on my mood or behaviour) of believing the AT/image, especially when I don’t yet know if it’s true? 5b.What’s the effect of modifying my thinking? Cognitive treatment of depression Appendix 1.A. Cont. 43 44 Kevin T. Kuehlwein Appendix 1.B. Some interesting quotes relevant to therapy Theodore N. Vail: Real difficulties can be overcome; it is only the imaginary ones that are unconquerable. Norman Vincent Peale: Change your thoughts and you change your world. SEEN ON A T-SHIRT: It’s never too late to have a happy childhood. Confucius: To be wronged is nothing unless you continue to remember it. Oscar Wilde: To become the spectator of one’s own life is to escape the suffering of life. Bertrand Russell: Fear is the main source of superstition, and one of the main sources of cruelty. To conquer fear is the beginning of wisdom. Aristotle could have avoided the mistake of thinking that women have fewer teeth than men by the simple device of asking Mrs Aristotle to open her mouth. Viktor Frankl: Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way. Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner: Knowledge is produced in response to questions. And new knowledge results from the asking of new questions: quite often new questions about old questions. Horace: He who has begun has half done. Dare to be wise: begin! Dale Carnegie: Remember happiness doesn’t depend upon who you are or what you have; it depends solely upon what you think. Seneca: It is not because things are difficult that we do not dare: it is because we do not dare that they are difficult. Cognitive treatment of depression 45 Appendix 1.C. Examples of socratic questioning Situation: A client comes in feeling like a bad mother because of yelling at her misbehaving child. Socratic questions to consider asking her (note: you would not ask these all at once): 1. What makes you think you’re a bad mother? What signs are there that you’re a good mother? 2. How strongly do you believe this idea, “I’m a bad mother,” now? 3. On a scale of 0–100%, with 100% being the worst mother you could imagine, where would you fall? Where would other people put you on this scale? Why might they rate you differently? 4. How often would you say you act as a 100% bad mother? 5. How often do you yell at your kids? 6. Whom would you consider to be a good mother? 7. Would you say that [that person] has never yelled at her kids? 8. What would a good mother do after she’d yelled at her kids and felt bad about it? 9. In terms of becoming a better mother, how helpful is it to you to criticise yourself at this level of harshness when you do something wrong? 10. What’s the effect on your parenting of your criticising yourself so strongly for something almost all parents do at one time or another? What’s the effect on your mood? 11. If you truly don’t want to yell at your children in the future, what are some things you could work on in therapy? What are some other behaviours you could try when you get angry with them? 12. What were you feeling before you yelled at your kids? 13. What do you think would happen to your parenting skills if you worked on ways of reducing those self-critical thoughts and feelings that lead you to be more easily irritated in the first place? 14. Besides viewing yourself as a 100% totally bad mother, what’s another way you could look at what happened? Notice what sorts of information this exercise can help you to a) gather about a client’s belief system b) impart to her new information to help her think differently about herself and her problem c) orient the client to thinking in more problem-solving ways Note also how the above questions mostly generate open-ended (non-yes/no) responses that flesh out the client’s ideas about herself and the way the world is or should be. 46 Kevin T. Kuehlwein Here are examples of Non-Socratic questions/comments in the same situation. (Note how much less useful they are in terms of helping the client to think differently or gather new information.) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Why are you being so hard on yourself ? What’s the big deal about yelling at your kids? Almost everyone does it. Didn’t your parents ever yell at you? I’m sure your kids will get over it. It doesn’t seem so bad to me. You’re basically a great mother; don’t you remember what you told me you did for your kids the other day? Alternative views of this evidence Evidence supporting NCB ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Actions I could take this week to increase my confidence in my NCB: ___________________________________________________________ Evidence seeming to support OCB Incident linked to highest: _________________________________ Highest this week: _____% Incident linked to lowest: ________________________________ Strength of belief now: _____% Lowest this week: _____% New core belief (NCB): ______________________________________________________________ Incident linked to highest: _________________________________ Highest this week: _____% Incident linked to lowest: ________________________________ Strength of belief now: _____% Lowest this week: _____% Old core belief (OCB): ______________________________________________________________ Cognitive treatment of depression 47 Appendix 1.D. Revising core beliefs Bob (friend) walks by without saying hello Bob (friend) walks by without saying hello [SAME] Maladaptive pattern More adaptive pattern Situation Disappointment, mild concern, puzzlement Sad, hurt Emotion That’s strange. He didn’t acknowledge me like he usually does. I wonder what’s up He’s ignoring me. He must be mad at me. (Personalization, mind-reading errors) Thought (No physiological symptom) Call him up later just to check in and mention casually that I saw him but he didn’t seem to see me Pain in the pit of my stomach. Later: I don’t return his phone call for several days to “punish” him Behaviour/physiological response Advantage: I don’t feel lousy because of faulty “mind reading”. I find out immediately whether there is something wrong with him or whether he’s upset with me so I can then decide what I want to do and I don’t have to worry about this Disadvantage: I put distance between him and me. I don’t explore what’s going on with him if there is a problem with our relationship Advantages/disadvantages 48 Kevin T. Kuehlwein Appendix 1.E. Old and newer patterns graphically represented Chapter 2 Cognitive behavioural treatment of suicidal behaviour Arthur Freeman and James Jackson Suicide, parasuicide, or self-injurious behaviour are situations of crisis for patients, therapists, and the significant others of both. Whether the actions leading to potential self-destruction or self-harm are active acts (ingesting poison, shooting oneself), threatening (collecting pills, cutting in non-lethal ways) or passive acts (not taking required medication), all have the potential for danger. Because they can all lead to or hasten one’s demise, any and all self-damaging behaviours must be addressed in as expeditious a manner as possible. Even the most experienced therapist reacts with an adrenaline surge of fear when it becomes clear that a patient has placed a time limit on life or safety. Given the severity of the consequence of the self-injurious or suicidal behaviour, it is essential for the therapist to have an understanding of the causes, assessment, process, and treatment of suicidal ideation, actions, or of self-injurious and parasuicidal behaviour. The nature of the problem requires that effective problem-solving be initiated immediately, and that follow-up treatment be initiated to minimise the relapse and return of the suicidal thoughts and actions and the subsequent danger. One of the foremost treatment models for the treatment of suicidality is cognitive therapy (CT) (Freeman & Reinecke, 1993; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979b; Freeman, Pretzer, Fleming, & Simon, 1990; Freeman & White, 1989). By definition, cognitive therapy is a short-term active, directive, collaborative, solution-oriented, psychoeducational, and dynamic model of psychotherapy originally developed for the treatment of depression, and is ideally suited for the treatment of the hopelessness and suicidality related to depression. Understanding the problems of the suicidal individual in terms of the individual’s idiosyncratic and negative beliefs about self (I’m no good), the world (“It” is unfair) and the future (“It” will never change), helps to organise the treatment and lend structure to therapy. Hopelessness, the third leg of what Beck termed the “cognitive triad” (Beck et al., 1979b), is a key part of the suicidal thinking. Clinically, it is useful to view a suicide attempt as an indication that an individual is hopeless and sees few or no options available to effect a desired change. A diverse set of therapeutic strategies and 50 Arthur Freeman and James Jackson techniques have been derived from this theory which have proved useful in providing a future focus for suicidal patients thereby increasing a sense of hope. Secondly, several techniques will be described that have the effect of helping patients in developing alternative solutions for their difficulties. Myths and realities A substantial portion of the clinical lore developed about suicide is based on clinical lore rooted in untested theories and/or limited understandings of theoretical and clinical concepts. Basing clinical decisions on clinical mythology rather than clinical psychology may likely result in either an over- or underassessment of lethality, over- or underestimation of risk, difficulty in conceptualising the problem, and, most seriously of all, difficulty in planning treatment and the consequent implementation of effective treatment strategies. Some of the mistaken beliefs about suicide commonly held by clinicians include the following. 1. Suicide is a cry for help In viewing a suicide attempt as a cry for help, one may underestimate the severity of the patient’s plight. Given the strong relationship between hopelessness and suicide (Beck, Steer, Kovacs, & Garrison, 1985), suicidality is most likely an indication that the patient believes he or she is far beyond help rather than the suicidal behaviour being a “cry for help”. 2. Talking about suicide reduces the risk This idea is based on the belief that talking about an impulse will somehow deplete its energy. A number of studies suggest that from 60% to 80% of persons who committed suicide have talked about it beforehand (Pokorny, 1960). Talking about suicide can increase, decrease or have no effect on the likelihood of suicide depending on the content of the discussion, context of the discussion, participants to the discussion and the patient’s reaction to all of the above. 3. Suicidal “gestures” are not to be taken seriously The patient who makes a suicide attempt and immediately calls for help, who “attempts suicide” using a non-lethal method, or who carefully times the attempt so as to be discovered before substantial damage occurs, may be seeking some effect other than death. However, despite the apparent ambivalence or manipulative intent, there are at least two good reasons not to simply dismiss the act as a “gesture”. First the patient may miscalculate the rescue potential making rescue impossible. Second, if the “gesture” does not achieve the desired response and the significant others or therapist do not actively intervene, the patient may initiate more extreme “gestures”. 4. Suicide risk can be determined from demographic factors While suicide rates may vary with criteria such as sex, age, social support etc., an over-reliance on Cognitive behavioural treatment of suicidal behaviour 51 such assessment criteria will lead to overestimation of risk with some patients and underestimation with others. 5. Suicide runs in families Although the data from twin studies have been examined and concordance rates for completed suicides are higher for monozygotic than dizygotic twins (Juel-Nielson & Videbeck, 1970; Tsuang, 1977), none of these studies managed to investigate monozygotic twins reared apart. Although tentative evidence exists that genetics play a small role in suicide, no methodologically sound study has adequately demonstrated the connection. Child abuse (Rogers & Luenes, 1979), early loss of parents (Stein, Levy, & Glassberg, 1974), and modelling of suicidal behaviour by significant others (Garfinkel, Froese, & Hood, 1982) all appear to place the patient at greater risk. 6. Talking openly about suicide may suggest it to the patient Novice therapists are often reluctant to address directly the topic of suicide out of fear of “putting the idea in the patient’s head” or of making the idea more acceptable if he or she is already thinking about it. Significant clinical experience shows that explicit discussions of suicide in therapy make it possible to address the issues directly and more likely reduce the suicidal risk. 7. Patients are more likely to make suicide attempts as they get less depressed This notion is largely false and directed toward a specific group of individuals with severe depression. Vegetatively depressed patients normally lack the energy to plan and carry out a suicide attempt. With a lessening of the depression and increase in energy, he or she may then make a suicide attempt if suicidality persists while the depression lifts. However, the more typical depressed individual does not become more suicidal as his or her depression lifts. Increasing hopefulness will reduce suicidality as problems are overcome. 8. Holidays are a time of increased suicide risk Quite simply, no evidence exists to substantiate the popular notion that higher rates of suicide, hospitalisation, or depression occur at holiday time (Christensen, 1984; Lester & Beck, 1975). Moreover, data suggest that the suicide rate and rate of attempts is greater in the spring (Rogot, Fabsitz, & Feinleib, 1976). 9. If the patient was serious about suicide he or she would not bring it up in therapy A high proportion of persons who go on to commit suicide do, either directly or indirectly, communicate their intent to significant others (Robins, Gassner, Wilkinson, & Kayes, 1959). While evasiveness in talking about suicide is a bad sign, willingness to talk openly about suicide does not necessarily mean that the risk of suicide is low. 52 Arthur Freeman and James Jackson 10. If someone is serious about suicide you cannot really stop them Measures to permanently prevent a determined patient from committing suicide do not exist. However, this does not mean that the therapist is helpless when confronted with a seriously suicidal patient. Since episodes of serious suicidality are usually time limited, simply delaying the attempt may allow time for the immediate crisis to pass. If the patient who seriously intends to take his or her own life begins to believe that he or she has more or better options, the press and stress of wanting to die will be reduced. 11. Medication can stop suicidal behaviour In an attempt to limit the suicidal behaviour, many non-medical therapists will react to suicidality by immediately referring the patient to a psychiatrist for antidepressant medication. Since most antidepressants require from one to three weeks before they have a substantial antidepressant effect, the use of medication may be too late to bring about an immediate reduction in suicidality. Moreover, tricyclic antidepressants can be quite lethal in overdose and may provide a convenient means for suicide. Antidepressant medication can be useful, but it is neither necessary nor sufficient in the treatment of suicidality. 12. Suicidal patients must be hospitalised Related to the medication myth is the notion that the suicidal patient must be immediately hospitalised. It is obvious that hospitalisation will be required if the therapist is not able to intervene effectively on an outpatient basis enough to eliminate the immediate danger to the person. If hospitalisation is the therapist’s primary response to suicidality and other less drastic and dramatic interventions are not tried first, patients will often become more hopeless. However, if there is concern for the individual’s ability for self-control, there is no active support system, or poor impulse control, a hospital environment may be a good choice in that the patient can be placed under careful observation. Another aspect must also be entertained. If the patient has a good support system, taking them out of that system may remove a powerful deterrent to the suicidal behaviour. 13. Patients with well-developed plans or methods are more likely to make an attempt Although patients with well-formulated plans or the means at hand present far greater risk of suicide, the absence of a plan does not eliminate the risk of an attempt. Patients with poor impulse control are at particular risk at any point because they lack the internal controls necessary to avoid selfdestructive action. 14. Patients have a right to take their own lives The case has been made that no one has the right to interfere with an individual’s existential freedom to live or die. However, it has been our experience that few patients select suicide as a free choice but rather feel compelled to attempt suicide by virtue of their Cognitive behavioural treatment of suicidal behaviour 53 perception that no other options are available to them. Thinking that they have no freedom at all, they are governed by dysfunctional thoughts that dictate the single option of death. The goal of therapy is to enhance the patient’s free will, not restrict freedom of choice. Clinical assessment An immediate and complete clinical assessment of suicide risk is important both as a part of the initial evaluation for therapy and throughout the therapy whenever indications of possible suicidality appear. The therapist must take any indications of suicide seriously and evaluate them carefully. Detecting early signs of escalating suicidality can require considerable sensitivity on the part of the therapist to subtle distinctions in meaning. The statement “I would like to die” may, for one patient, mean that while death is attractive as an escape from problems, he or she has no intention of hastening his or her demise. For another patient, the same statement may indicate that he or she intends to take active steps towards suicide or even has started implementing a plan. Even the most sensitive clinician cannot safely assume that he or she fully understands the meaning of suicidal ideation without asking the patient directly about the beliefs, actions, and thoughts. Similar care must be utilised for assessment of subtle behaviours that reflect suicidal ideation or intent. The patient who updates his or her will, begins completing unfinished details of life, or is giving away possessions may well be in the process of implementing a suicide plan and merits evaluation. Similarly, expressions of increasing hopelessness or vague comments such as, “If I’m still around next month, I’ll . . .” can be important warning signs. Early detection may allow for intervention before a crisis arises. In assessing suicidality, obtaining an understanding of the patient’s view of his or her options is critical. The patient who sees few or no options is at far greater risk than the patient who maintains that options, although limited or undesirable, exist. In making a clinical assessment of suicidality, the clinician must be aware of his or her cognitions so that information is not lost or never sought in an attempt to gain a modicum of comfort. The therapist who is discomforted by the idea of discussing suicide may be collaborating actively with the patient’s suicide attempt. Other factors to consider in assessing the potentially suicidal patient include: Has the patient made previous attempts? When was the last attempt? How frequent have the attempts been? What were the circumstances of the attempts? Is there a family history of suicide? Have either parents or grandparents made suicide attempts? Have these attempts been successful? A number of tools are available to aid clinicians in the assessment of suicidality. The Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition, a 21-item self-report measure of depression (BDI-II, Beck, 1996) can offer the clinician a measure of the patient’s general level of depression by using the total BDI 54 Arthur Freeman and James Jackson score. The clinician can also assess the specific areas of depression by examining the specific items endorsed by the patient. Of particular importance are the patient’s responses to item 2 (hopelessness) and item 9 (suicidality). The Hopelessness Scale (Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, 1975) directly assesses the hopelessness component of depression. Inasmuch as the cognitive model sees hopelessness as the prime ingredient in suicide, such direct assessment is essential. By evaluating both the overall score and changes in the score over time and conducting a content analysis, the therapist can develop a conceptualisation of the problems that are fuelling the patient’s suicidal thinking as specific themes will emerge from the scale. The Scale of Suicidal Ideation (SSI; Beck, Kovacs, & Weissman, 1979a) provides a useful framework for assessing factors including the patient’s thought, his or her intentions regarding suicide, and any plan the patient has formed. This measure can be used in two ways. First, it can be used as part of a structured interview with the clinician asking the necessary questions to obtain the information sought by each item. Questions in each area are asked in the same manner with the therapist asking for elaboration on any item that appears to be important. Since suicidality is not a trait, it is best assessed at different times and situations throughout the therapy. The SSI can also be used as a self-report measure with the patient indicating in a forced choice manner which response best fits their situation and thinking. It is important to distinguish between thoughts of suicide, suicidal intent, and potential lethality of a chosen method in assessing suicidality because the three can be quite independent of each other. The clinician should be particularly aware of the potential lethality of a number of suicidal behaviours and not underestimate any of them. For example, the ingestion of any quantity of drugs with the intention of dying must be viewed as a lethal attempt, even if the ingested drug has a wide margin of safety and low lethality. Suicidal thoughts can take the form of obsessions which the patient may find distressing or repugnant rather than appealing. Careful assessment may reveal that in spite of the presence of suicidal thoughts, the patient may have no intention of committing suicide. Use of a non-lethal method in a suicide attempt may create the impression that the attempt was manipulative and not serious, but it is important to assess the patient’s intent rather than jumping to conclusions. For example: A 24-year-old woman despondent over a lost love made all the plans to die of asphyxiation. She closed her kitchen window tightly and stuffed kitchen towels around the kitchen door to make it airtight. She then turned on the oven and put her head in the oven so she could breathe deeply of the gas. Her oven, however, was electric and all she did was singe her hair. Although the attempt may seem comic, her intent was most serious. The good news was that her attempt failed. However, it is clear that this woman had very poor problem-solving strategies which is certainly the bad news in this case because her problem-solving deficits leave her vulnerable to later Cognitive behavioural treatment of suicidal behaviour 55 attempts. In addition, her impulse control was flawed which is another poor prognostic indicator. Without effective intervention, this patient might well have learned from her experience and have chosen a more lethal method for her next attempt. Similarly, an action which is intended as a suicide gesture rather than being taken without the intention of dying can still be fatal if the patient miscalculates. It is important to take so-called “manipulative” suicide attempts seriously, not only because they can prove fatal despite the intent, but also because there is no guarantee that “serious” attempts will not follow. For example, a 28-year-old man was seen for therapy subsequent to a near-lethal suicide experience. We have not used the term “attempt” inasmuch as the man stated that he did not plan to die, but only to “frighten and inform my wife of my pain”. He had taken several pills from a bottle in the medicine cabinet. He did not check what the pills were, thinking them to be his wife’s diet pills. They were, in fact, a common medication that in combination with the antihistamine that he regularly took for his allergies put him into respiratory difficulty. Fortunately, he was able to call for emergency help. When his wife came home for dinner she found him gasping for air on the floor while emergency medical technicians worked on him and later transported him to a hospital emergency room. Vulnerability factors Factors that result in lowering an individual’s ability to cope with stress are known as vulnerability factors. A vulnerability factor has the effect of decreasing the threshold so that events that were previously ignored or never noticed now shout loudly for attention. The vulnerability factors also serve to make the individual more sensitive to internal and external stimuli that may affect the suicidal thoughts and actions. A tenet of Alcoholics Anonymous is to make members aware of the acronym HALT. The letters stand for Hungry, Angry, Lonely, and Tired. AA emphasises that these are conditions under which an individual is most likely to lose control and resume drinking. These are not the only vulnerability factors. Others include chronic pain, acute pain or illness, substance abuse, any major life loss, or a major life change. The patient can be asked to rate each factor on a scale of 1 to 5. One represents “doesn’t affect me at all”. Five represents “bothers me greatly”. The patient can also be asked to rate these separately for how they affect their feelings (Do they sense an emotional change?), their thoughts (Do thoughts about this factor tend to occupy their mind?), and their behaviour (Do they act differently when this factor is present?). The higher their score on an individual factor, the more important that factor is to them. 56 Arthur Freeman and James Jackson Feelings Thoughts Behaviour 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1. Hunger 2. Anger 3. Substance abuse 4. Loneliness 5. Fatigue 6. Pain 7. Illness 8. Major loss (job, etc.) 9. Lack of sleep 10. Major life change A cognitive behavioural conceptualisation of suicidal behaviour In fact, when the relationship between hopelessness and suicide is taken into account, the relationship between depression and suicide seems more apparent than real, with the apparent relationship due primarily to the high incidence of hopelessness among depressed individuals. Everson and her colleagues (Everson, Goldberg, Kaplan, Cohen, Pukkala, Tuomilehto, Salonen, & Jenkins, 1996) found that when all risk factors were controlled, men who evidenced higher levels of hopelessness had a higher mortality rate, increased chances for myocardial infarction, a greater chance of dying in an accident or due to violence. Clinical observation and study from any theoretical perspective would show that clinically depressed individuals systematically view themselves, their world, and their future in a negative manner. The individual’s cognitive processes are characterised by a sensitivity to several reactions including feelings of loss or feelings of abandonment. Suicidality, however, is believed to result from consequent feelings of hopelessness, in conjunction with a belief that current difficulties are unendurable, or from a desire to manipulate or rapidly gain control of a frustrating or threatening situation. These Cognitive behavioural treatment of suicidal behaviour 57 difficulties are compounded by a perceived lack of alternative choices, supports, or coping mechanisms. Suicidal patients tend to view their world in a “constricted” manner, in that they are relatively incapable of identifying alternative courses of action, or of rationally examining the validity of their belief that their problems are serious or unendurable. While suicide is an option for anyone, the majority of individuals never exercise this option because they see more promising options for dealing with their problems. At the bottom of most people’s list of options, suicide only becomes an issue as the individual exhausts other options and gets closer to the bottom of their list. Although research suggests that it is the most robust predictor of suicide, hopelessness is not the only factor which can lead to suicidality. A discussion of a number of variations on the hopelessness theme may help the therapist gain a better understanding of suicidal thinking and behaviour. We would divide suicidal behaviour into four broad types: hopeless suiciders, histrionic or impulsive suiciders, psychotic suiciders, and rational suiciders. None of these types is mutually exclusive with any of the others. The first type, the hopeless suicider, believes that there are few, if any, options for them in life. The single option that they see as the most effective measure for coping is to kill themselves. What is interesting is that each of us has a number of options that we might exercise in any situation. One person may have one hundred and fifty options. Another may see themselves as having fifteen options and another may see themselves as having five options. For the first person, suicide is a far distant option that does not enter their mind or play a part in their decision making. For the second individual it is a frequent thought and plays a part in their decision making. For the third individual, it is a constant part of their cognition. If for reasons beyond their control, each of these individuals loses four options, person one remains at ease, person two is in an increased state of upset, person three sees no options and may be acutely suicidal. The histrionic or impulsive type of suicide attempt is motivated by a desire for arousal, excitement, and/or attention. They will often seek increasing levels of stimulation. Some individuals crave activity and excitement and when feeling anxious, nervous, “itchy”, or bored, will seek out high risk or “exciting” activities such as consuming drugs or alcohol in quantity, speeding in cars or motorcycles, or deliberately entering dangerous situations. The net result may very well be physical damage or loss of life. This type of individual may even use the suicide attempt as a source of stimulation or excitement. Part of the overall symptom picture of the histrionic attempter is that the suicide attempts are flamboyant and may be repetitive. These attempts may be questioned as actual suicide attempts and be classified by the clinician as manipulative or motivated by needs for attention. Even when this is true, the possibility of a histrionic attempt being lethal exists, so that the ideation and attempts still need to be taken seriously. The following case serves to illustrate this type of attempter: 58 Arthur Freeman and James Jackson A 27-year-old man recounted several severe “suicide attempts” (labelled as such by a previous therapist). He reported that he often would be in his home at night and would start feeling what he termed “itchy” or nervous. His manner of coping with nervousness was to do one of two things. The first was to drive his car at great speeds on a highway at night, often exceeding 100 miles an hour. At times he would turn his headlights off and drive only by moonlight. He reported a great relief after these driving episodes. His “anxiety” was relieved, and he could then return home to sleep. His second strategy for relieving his nervousness was to drive along back roads to small highway bridges over streams or creeks and to jump from bridges. He would get wet and muddy, but, in spite of the potential for danger, was never injured. These attempts may be questioned as actual suicide attempts, but the ideation and attempts must be taken seriously as the possibility of lethality clearly exists. A third group of individuals attempt suicide as a direct result of command hallucinations, or voices from within (Roy, Mazonson, & Pickar, 1984; Gardner & Cowdry, 1985). It is very important to assess whether the attempt is psychotic or not, for in psychotic individuals it is not hopelessness per se that must be addressed but rather the voices or impulses that are prompting them to consider or act on the command. The primary intervention with patients who are experiencing command hallucinations would be pharmacological (i.e., the use of antipsychotic medication that would have as its function a reduction in the delusional system and/or hallucinatory phenomena). In addition, however, the therapist can help the patient learn skills to gain power over internal stimuli by teaching the patient to forcefully counter the commands by generating effective self statements. The patient can be taught to view the commands as “not all powerful” requiring no immediate response. The fourth type is the rational suicider. These are the individuals who have chosen to die on the basis of some rational consideration. These individuals rarely seek therapy to discuss their rational decision, so that therapists generally see these individuals after a failed attempt. The type of situation generally offered as the model for rational suicide is that of the terminally ill cancer patient in intractable pain. These patients come under the broad heading of “right to die”. Whenever a patient demands that life support systems be terminated, the intended result is that death would follow shortly. One manifestation of the right to die comes with the patient’s decision to ask the medical staff to agree to affix the label DNR (do not resuscitate) on the patient’s medical chart. The patient has made the choice, often in conjunction with family and significant others, that should the patient’s condition deteriorate, and they need resuscitation, none would be given. No ambulance would be called to a convalescent home or care facility, and no extraordinary measures would be employed to keep the patient alive. The issue of an individual’s right to die is a bio-medical-ethical-legal issue that is still hotly debated by ethicists, physicians, legislators, theologians, Cognitive behavioural treatment of suicidal behaviour 59 hospital administrators, attorneys, and hospital risk managers. We have found that many individuals who think that their suicidal thoughts are the most rational, reasonable, and intelligent course of action can, with therapy, see other options. We are not, however, ruling out the possibility of an individual making a rational choice and the need for the therapist to aid the client in making that choice. The need for the therapist to be prepared for sensitive discussions, and for a testing of the therapist’s own schema regarding death and dying, is quite powerful. Strategies for intervention A full understanding of the cognitive model is essential for any therapist planning to use cognitive therapy (the reader is referred to Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979b; Freeman, 1988; Freeman, Pretzer, Fleming, & Simon, 1990; and Freeman & Reinecke, 1993). Therapy cannot be a mere collection of strategies and techniques. Rather, an understanding of the cognitive underpinnings of suicidal ideation and intent is required. With that conceptual framework, the cognitive therapist can understand quickly the nature of the suicidality and develop interventions, both inter- and intrapersonally. Specifically, cognitive therapists work in a very direct manner with patients, proposing hypotheses, developing strategies for testing the hypotheses, developing a range of specific skills as needed, and teaching the patient a model for more effective coping/adapting to the world. Probably no patient population requires a direct problem-solving approach as much as the suicidal patient. Such individuals have been found, for example, to demonstrate deficits in their ability to generate and evaluate alternative solutions or viewpoints. This “cognitive rigidity” is reflected in their relatively poor performance on measures of social problem-solving, such as the Means-Ends Problem Solving Task (Platt, Spivak, & Bloom, 1975; Reinecke, 1987; Schotte & Clum, 1987). The process of cognitive therapy is based on collaboration between patient and therapist. With the severely depressed and suicidal individual, the therapist’s activity level must be high enough to supply the initial energy to develop the therapy work, so that the collaboration might start out 80–20, or even 90–10. Because of the seriousness of the patient’s condition, and the severity of the consequences, the therapist cannot rely simply on offering a restatement of the patient’s problems but must use an active restructuring of thoughts, behaviours, and affect. A problem focus is essential with the suicidal patient to help supply a direction for therapy rather than encourage a vague and aimless wandering about the broad issue of hopelessness. The initial goal is to work quickly to establish rapport. The therapist must be perceived as an individual who can be trusted, supportive, confident, resourceful, and available, and someone who is perceived by the patient as an ally. The therapist’s openness and lack of selfconsciousness in directly questioning the nature of the patient’s hopelessness 60 Arthur Freeman and James Jackson and thoughts of suicide, the utilisation of the data from the psychological measures, integrating the patient’s history, and level of depression, can all serve to put the patient at greater relative ease. They will have the confidence that their problems are not so great that even the therapist is overwhelmed. Having established rapport, the therapist needs to work actively and directly on the hopelessness. The patients must be worked with rather than on, so that he or she feels part of a therapeutic team. This is especially important with suicidal patients who must see that they can, as a result of therapy, develop alternatives and options. They need to appreciate that it is not merely the therapist telling them what to do or giving them instructions. This might feed into their hopelessness with the belief, “See I can’t even manage my life, I need to be told what to do.” The therapist should bear this in mind when working with the suicidal patient whose energy level is low, who feels paralysed, and whose general level of motivation may be lacking. For the individuals who have settled upon suicide as the option of choice, the therapist may need to contribute more to the collaboration until the patient is able to make the decision that there might be a future, that there may be things that the patient can do, and that it is possible to change. Simply being a “cheerleader” who tries to distract the patient into looking at the positive side of things is not enough. If it is possible to reach the point where the patient makes a believable commitment to refrain from suicide attempts while the therapist and patient try other approaches to overcoming the patient’s problems, the therapist and patient can then take steps to minimise the risks of a suicide attempt should a crisis arise, and begin working on the patient’s problems using the usual cognitive therapy approach. If the patient will not make a believable commitment to refrain from suicide, is not willing to take steps to dismantle his or her suicide plan, or if the patient makes it clear that he or she is still planning to attempt suicide, the therapist must take decisive action. The options at that point include voluntary or involuntary hospitalisation, and contacting the patient’s significant others to involve them in intervention. It is the therapist’s responsibility to do all that is within his or her power to minimise the risk of suicide. Initially, the therapist and his or her patient are likely to have conflicting goals in mind since the patient is at least considering suicide and the therapist’s primary goal is to keep the patient alive. This obviously makes it difficult to use a collaborative approach unless therapist and patient can identify a goal towards which both are willing to work. Often the goal of trying to determine whether suicide is a good idea or not is a good starting place. For example: a therapist might say, “It sounds like you’re pretty certain that suicide’s the best option you have in this situation. This is something I think is important to take seriously. With most decisions people have the option of changing their minds if it turns out that they’ve made a poor choice but with suicide you don’t get to try something else if it turns out you Cognitive behavioural treatment of suicidal behaviour 61 weren’t thinking clearly. Would you be willing to take a look at whether suicide is really the best option you have?” With this rationale, it is usually possible to take a collaborative approach with even seriously suicidal patients. The therapist is then in a position to clarify the patient’s motivation for suicide and his or her expectations regarding the likely consequences of suicide. The full range of interventions which are used in looking critically at automatic thoughts can be used in looking critically at the patient’s views regarding suicide. Whatever the motivation for suicide, it can be quite valuable to help the patient to look carefully at the evidence supporting his or her conclusion that suicide is necessary and will accomplish the desired ends, as well as looking at the alternatives to suicide. An intervention at this point might be contracting with the patient to act in a non-suicidal manner. This will be discussed later in the chapter. It is important to help the patient verbalise his or her hopelessness and then to look critically at his or her conviction that the situation is hopeless. What evidence convinces the patient that the situation is hopeless? Will the hopeless situation last for ever? Is it totally unchangeable? Might there be options for dealing with his or her problems that the patient has overlooked? When patients are helped to examine their situation, they are often able to see the distortions in their logic and discover that the situation is not nearly as hopeless as it appeared. For example: When Kathy, a divorced mother of one, first described her situation to her therapist, she was convinced that since she felt she couldn’t return to her job but couldn’t support herself and her son without a job, the situation seemed truly hopeless. However, when she and her therapist carefully examined the work and life situations in detail, it became clear that Kathy and her son would not perish if she quit her job. Actually she had a number of alternatives: she could use her savings for a few months and look for a new job, she could work on a part-time basis, she could ask her parents to help her out financially if she really needed it, or any combination of the above. Once it was clear that the situation was difficult rather than hopeless, her suicidality subsided and her mood improved considerably. Other assumptions such as, “They’ll be better off without me”, “Nobody will miss me”, or “I’d be better off dead” can often be handled in a similar way. In addition to questioning what would be accomplished by suicide, it is important for the therapist to work on significant reasons not to commit suicide. It is obvious that one of the major drawbacks to suicide is that the individual forfeits the rest of his or her life. However, this is seen as a good reason to refrain from suicide only if the individual has a significant amount of hope that life can be worth living. With hopeless individuals, in particular, it is important to identify reasons to refrain from suicide that do not rely on hope for the future. These deterrents might include the likely effects of the patient’s suicide on family and friends, religious prohibitions regarding suicide, fear of surviving an attempt but being seriously injured, concern about what others will think, and so on. It is usually necessary for the therapist to 62 Arthur Freeman and James Jackson take an active role in generating possible deterrents, but this can be done most effectively if the therapist works to engage the patient in the process rather than simply listing the reasons he or she sees for the patient not to commit suicide. Explicitly listing the advantages and disadvantages of continuing to live and separately the advantages and disadvantages of suicide can be an effective way of integrating the results of the above interventions. This will have the additional benefit of providing the patient with a concise summary of the conclusions reached during the therapy session, to which he or she can refer if suicide should again start to seem like a promising option. For example, the thought, “I would be better off dead” can have an enormous impact as long as it is accepted without critical examination and patients may have difficulty challenging such thoughts on their own if they have not been in treatment very long. A concise summary of the major conclusions reached in each therapy session can be quite useful to patients when suicidal thinking re-emerges between sessions. In initial interventions with hopeless patients, it is not necessary for the therapist to attempt to convince the patient that all problems will be overcome, that the alternatives to suicide will definitely be successful, or even that suicide is always unacceptable as an option. All that is necessary is (1) to raise doubt regarding the merits of suicide and, (2) to identify sufficiently promising alternatives to suicide so that (3) the patient is willing to make a commitment to refrain from suicide attempts while (4) the therapist and patient explore other options. It is important for the therapist to accept the patient’s scepticism and not to encourage unrealistically optimistic expectations which are likely to lead to sudden disappointment. Reluctant patients are often more willing to refrain from suicide for a reasonable period of time if the therapist points out that by agreeing to this approach the patient is not giving up suicide as an option. For better or worse, the patient will always have the option of choosing to commit suicide later should it ever turn out that suicide is the best option available to him or her. Cognitive therapy generally emphasises a guided discovery approach rather than a more confrontational, disputational approach. However, when the therapist is faced with a hopeless patient who is not willing to participate actively in the process described above, it is important to actively dispute the patient’s distortions and misconceptions, and to present possible alternatives to suicide even if this must be done with minimal participation by the patient. While active disputing can be useful, the therapist must walk the very fine line of not arguing with the patient. There are important advantages to involving the patient in this process as much as possible, but if guided discovery is not feasible, direct disputation may prove effective. If it is effective, then the therapist should be able to shift to a more collaborative approach as the patient becomes more willing to look at alternatives to suicide. Once it is clear that suicide is not a promising option and that there are important reasons not to Cognitive behavioural treatment of suicidal behaviour 63 commit suicide, the patient may still see no viable alternatives to suicide. It is also important for the therapist to help the patient to identify the possible alternatives. If the therapist only takes the approach of trying to elicit options from the patient, a rather limited list is likely to be generated. If the therapist takes a brainstorming approach and raises possibilities of his or her own and encourages the patient to consider options that, at first glance, seem absurd or unworkable, it is possible to generate a much larger pool of possible alternatives to suicide to choose from. Options which strike the patient as unworkable may well prove to have more potential than was immediately apparent or may suggest other, more feasible options. Having perceived the advantages and disadvantages of suicide as well as having identified alternatives to suicide, the therapist and patient can agree on a course of action and pursue it. An important part of this agreement is the patient’s making a believable commitment or contract to refrain from suicide for a reasonable period of time during which therapist and patient will work to overcome his or her problems. The agreement should also include the patient’s agreeing to call and talk with the therapist (not just leaving a message) before actually doing anything to harm him- or herself. Some therapists make a practice of having the patient sign a written contract containing these and other provisions, and doing so would have an advantage with patients who take written agreements more seriously than verbal agreements. However, the key element is the agreement and the clinician’s judgement as to whether the patient’s commitment is genuine, rather than the contract per se. This point is emphasised by one patient’s response to the therapist’s suggestion that he sign a written contract. “So what are you going to do if I kill myself, sue me?” The contract, whether spoken or written, is not intended to be enforceable by law, but is one stage of a collaborative approach to dealing with suicidality. The therapist and patient should try to anticipate any situations which would be likely to produce a sudden increase in suicidality and plan how the client can best cope with them should they arise. An important early intervention is to work with the patient to dispose of any available means for suicide that the patient may have selected. This might include steps such as asking an individual who collects guns and who had planned to shoot himself to turn the guns over to the police, to place the guns in the custody of a reliable significant other, or even to bring them to the therapist. The purpose of such precautions is not to make suicide impossible but to decrease the risk of an impulsive suicide attempt by making the means of suicide less accessible. It is best to design precautions so that it is possible to confirm that the patient has complied with them, since otherwise the therapist may face some difficult decisions. For example: One patient reported that he had three handguns loaded and available to use for a suicide attempt. After a rather lengthy discussion, he agreed to turn the guns over to his brother who would keep them indefinitely. The patient was asked to call the therapist that evening to confirm that the guns had indeed been turned over to his brother. 64 Arthur Freeman and James Jackson Instead, what the patient reported was that he had changed his mind and rather than turning the guns over to his brother, he had gone down to the river, tossed the guns in a paper bag into the river and watched them sink beneath the waves. The therapist had no way of confirming whether the guns had been disposed of or not and therefore had to decide whether the patient’s assertions were true on the basis of little or no data. If the preceding interventions have been effective, and hospitalisation is not needed, the recently suicidal patient is likely to need closer follow-up than most patients. It is not unusual for cognitive therapists to meet with a patient two or three times per week during times of crisis or to arrange telephone contacts between sessions. It is important for the therapist or a colleague to be accessible to handle crises as they arise even if that means the patient calls late at night or on weekends. If sufficient therapist patient contact is scheduled throughout the week, emergency phone calls should be held to a minimum. With the above foundation, cognitive therapy can then proceed much as it would if the patient had not been suicidal. It is usually best for therapist and patient to work first on issues which are related to the motivation for suicide, which are important to the patient, and on which there is a good chance of making noticeable progress quickly. In addition, it is important for the therapist to be alert to any indications of increasing suicidality and to repeat the above interventions if a setback or crisis should produce a renewed risk of suicide. When suicidal impulses are a product of intense anger at oneself or others, it is clear that the optimal solution is to help the patient develop more adaptive ways of handling intense anger. However, since it is likely to take considerably more than a single session to accomplish this, it is important to deal effectively with the immediate crisis first. Once it is clear to therapist and patient that suicide would be an attempt to punish oneself or others, therapist and patient are in a good position to consider whether suicide is likely to be the best option for doing so. This is likely to include an examination of the patient’s expectations about the consequences of a suicide attempt, the degree to which he or she is certain that suicide will have the desired impact, the deterrents to suicide, and alternative ways to accomplish the desired results. It is also important to question whether the desired results are important enough to be worth the patient’s risking his or her life. The patient may not have considered the fact that suicide attempts which are not intended to be fatal can still be lethal. It is possible to identify alternatives to suicide which the patient would find emotionally satisfying and would be willing to try; these can be substituted for suicide as a way of “buying time” so that it is possible to work to help the patient develop more adaptive ways of handling anger. Even alternatives which the therapist would not normally suggest are worth considering such as throwing a temper tantrum, writing a nasty letter to the person who is the Cognitive behavioural treatment of suicidal behaviour 65 object of his or her anger, or marking his or her wrists with a marking pen rather than cutting them. While these are not very appropriate ways of handling anger, they are much better than suicide. Once the client has agreed to refrain from suicide for a certain period of time, it is important to proceed with agreeing on a certain treatment plan, dismantling any preparations for suicide, and periodically monitoring suicidality, as discussed above. Many patients who consider suicide out of anger, rather than hopelessness, manifest characteristics of borderline personality disorder. Such patients are likely to have problems with impulse control and methods and techniques for increasing impulse control are likely to be helpful. As with the angry suicidal patient, in working with the histrionic suicidal individual, it is important to identify the functions which would be served by a suicide attempt and to consider whether suicide is really a promising means for accomplishing those ends. Whether the goal of a suicide attempt is to reduce anxiety, to achieve a desired response from significant others, or simply to obtain stimulation and excitement, the process of exploring the pros and cons of a suicide attempt, the deterrents to suicide, and alternatives to suicide discussed in the above can be quite useful. In working with these patients, it is important for the therapist to be aware of his or her reactions to them. On the one hand, when the patient’ s talk of suicide seems manipulative, particularly if there is a history of apparently manipulative suicide attempts, it is easy to conclude that he or she is not “really” suicidal but is just being manipulative. One must remember that if the patient feels that his or her threats of suicide are not being taken seriously, he or she may feel that it is necessary to take more extreme steps in order to be taken seriously. On the other hand, histrionic patients can sometimes be quite skilled at inducing others to come to their aid, and the therapist can easily slip into trying to “rescue” the patient rather than working to get the patient to take an active part in therapy. To be effective, the therapist needs to avoid both extremes. As briefly discussed in the above, intervention with patients who are suicidal due to command hallucinations is quite different from intervening with other suicidal patients in that the primary intervention is pharmacological. Often medication alone is effective in reducing command hallucinations, and cognitive interventions are directed towards increasing the patient’s compliance with the medication regimen. In addition, it is possible to work cognitively to increase the patient’s ability to cope effectively with the voices once the medication has substantially reduced their floridly psychotic symptoms. The therapist working with patients having command hallucinations needs to know the precise nature of the commands. Thus, the patient must be questioned directly about the content and nature of the commands as well as his or her ability to resist them. Once the nature of the commands is understood, it is important to help the patient examine whether obeying the commands is a good idea. Individuals suffering from command hallucinations usually have 66 Arthur Freeman and James Jackson never stopped to consider what would be accomplished by obeying the voices and what would happen if they resisted. By raising this question, the therapist can start to lay a foundation for the patient’s choosing not to obey the voices rather than feeling compelled to obey. Standard cognitive techniques such as questioning the evidence may be employed in this regard. An approach as simple as “what evidence do you have as to whether it is a good idea to obey the voices or not? Have they given you good advice in the past?” can be quite effective in clearly establishing that resisting the commands is a good policy. Next the therapist and patient need to develop a plan for coping with the command hallucinations. If the patient has already discovered some partially effective strategies such as staying active or keeping his or her mind occupied, these can be incorporated into the plan. Patients often find it useful to minimise the amount of unstructured time in their day, to explicitly remind themselves that they do not have to do what the voices say, and to remind themselves that the voices give poor advice. Another standard technique known as externalisation of voices may be employed as a means of teaching the patient to “talk back” to the commands either by refusing directly, e.g., “I don’t have to. I won’t, I won’t, I won’t” or through more sophisticated responses such as, “I’m not going to. Suicide is sinful and it would hurt my family. And besides, if I can hold till my new job starts, money won’t be so tight and I’ll be able to get my own apartment again.” It can be particularly useful to have the patient write a summary of the most convincing arguments for resisting the voices and of the most promising coping strategies to aid him or her on remembering the plan for coping with the voices. It is also important to take steps to reduce the risk of an impulsive suicide attempt as discussed above. If the patient is chronically psychotic, then cognitive therapy is likely to be of greatest value in increasing the patient’s compliance with his or her medication regimen and in helping the patient deal more effectively with problem situations that arise. If the psychotic symptoms are acute and subside once the immediate crisis is over, then the usual cognitive approach to the patient’s remaining problems should prove effective. Use of significant others in therapy In any emotional dysfunction or distress, there are significant implications for the families, significant others, children, parents, spouses, extended family, friends, neighbours, co-workers and colleagues, students, fellow patients, therapists, physicians, police, and clergy (Dunne, Mcintosh, & Dunne-Maxim, 1987). Given the potential impact on family dynamics and overall functioning, it is important, useful and often essential to involve significant others in several aspects of the therapy. They may be part of the referral, assessment, treatment, and relapse prevention work. Cognitive therapists advocate early contact with significant others (Beck et al., 1979b; Bedrosian, 1981). Beck and colleagues believe that, in the absence Cognitive behavioural treatment of suicidal behaviour 67 of any obvious contraindications, the significant others should be interviewed immediately after the initial interview with a suicidal patient. Such an interview would yield data regarding the patient’s symptoms and level of functioning, the reactions of those close to the patient, and the nature of their interactions with the patient. This information may help identify sources of distress and alert the therapist, family, and patient to the types of experiences or situations which might trigger impulsive and potentially self-damaging behaviour. The significant others as sources of data The family members and other individuals that are significant and meaningful to the patient can be important sources of information about the patient’s life, personal history, medical or psychiatric history, social or developmental history, and the family schema. This can serve to provide the therapist with a more balanced view of the patient’s life. When patients are too young to report major life events, when there is some neurological disability, or when information is simply not available to the patient, the significant others can offer details that might otherwise be lost. During the therapy, family members can offer feedback to the therapist about the therapy and its immediate effects on the patient. The family’s involvement can foster mutual support or it can foster divisiveness. Family members may deny the seriousness of the patient’s behaviour, may disagree with the need for hospitalisation, may punish the patient for particular behaviours by criticising or withdrawing from them, or may label the patient or another family member as the problem. Others may deeply wish to be helpful, but lack the skills to communicate effectively with the patient or may behave in an oversolicitous manner. It is therefore necessary to assess both the strengths and weaknesses of those individuals making up the patient’s social environment. Such assessment will help the therapist decide whether to include couples work or family therapy in the treatment plan. With suicidal patients, it will help the therapist judge the risk of allowing the patient to remain in the company of those significant others. Significant others play a substantial role as the patient’s social environment, responding to him or her in ways that support treatment gains. Significant others may assist in therapy to the point of acting as auxiliary therapists, helping the patient to identify negative cognitions and respond to them. Because they tend to know the patient’s history, they can recall evidence the patient may forget or ignore. Summary Cognitive therapy is ideally suited for the treatment of hopelessness and suicidality for a number of reasons. Cognitive therapy’s short-term, problemfocused orientation lends itself to the initiation of the kind of effective 68 Arthur Freeman and James Jackson problem-solving interventions required in treating the suicidal client. A problem focus is essential to help supply a direction for therapy versus encouraging a vague and aimless wandering about the broad issues of hopelessness. In addition, cognitive therapy enables the therapist to make use of a variety of strategies and techniques that have proved useful in instilling in suicidal patients a sense of future and hope. It provides the therapist with a format for understanding the problems of the suicidal individual in terms of the individual’s idiosyncratic and negative beliefs about self, the world and the future. These factors exert a powerful influence on the individual’s decision to take his or her own life. By bringing into conscious awareness those aspects of the individual’s personal meaning system which generate feelings of depression and hopelessness, the therapist is provided with a specific focus for intervention. The model provides a methodology for the rather quick and accurate assessment and conceptualisation of the client’s problem, to be followed by a number of intervention strategies and techniques which have proved effective in the treatment of depression and hopelessness. Use of strategies such as Socratic questioning enable the therapist and client to work collaboratively in developing adaptive responses to dysfunctional thinking. In addition to cognitive interventions, a number of behavioural interventions may be employed as initial strategies with the more depressed and vegetative client. Once the client’s feelings of hopelessness are sufficiently under control, the therapist may then target other factors known to contribute to suicidal behaviour. Many suicidal clients have long-standing problems with poor impulse control and may have significant problem-solving and coping skill deficits. Because it is based on both a “coping” and a “mastery” model of therapy, cognitive therapy is highly suited for teaching clients more effective problem-solving and coping skills, thereby reducing their overall vulnerability to stress. Finally cognitive therapy incorporates a strong relapse prevention component as part of its comprehensive intervention strategy. The termination of formal treatment does not mean the end of therapy for the suicidal client. Trained to identify specific situations, events, cognitions and feelings which place him or her at risk for a return to suicidal thinking, the client is also trained in effective coping and problem-solving skills needed for successful intervention and interruption of the process. Empirical testing of the short-term, active, directive, focused, problemoriented, structured, collaborative and psychoeducational nature of cognitive therapy will undoubtedly result in changes to the basic model of treating suicidal behaviour. Since the therapist is often the only person standing between the client’s life and death, it is hoped that the strategies for assessment and intervention included in this chapter will help to provide the therapist with additional hope in undertaking what is often a stressful and daunting task. Cognitive behavioural treatment of suicidal behaviour 69 References Beck, A.T., (1996). Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd Edition. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation. Beck, A.T., Kovaks, M., & Weissman, A. (1979a). Assessment of suicidal intention: The Scale for Suicidal Ideation. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology, 47, 343–352. Beck, A.T., Rush, A.J., Shaw, B.F., & Emery, G. (1979b). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press. Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., Kovacs, M., & Garrison, B. (1985). Hopelessness and eventual suicide: A 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 559–563. Beck, A.T., Weissman, A., Lester, D., & Trexler, L. (1975). The measurement of pessimism: The Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 42, 861–865. Bedrosian, R. (1981). Ecological factors in cognitive therapy: The use of significant others. In G. Emery, S. Hollon, & R. Bedrosian (Eds.), New Directions in Cognitive Therapy. New York: Guilford. Christensen, R. (1984). The misdiagnosis of holiday and winter complaints: An unconscious shift in criteria? Psychotherapy, 21, 401. Dunne, E.J., Mcintosh, J.L., & Dunne-Maxim, K. (Eds.) (1987). Suicide and its Aftermath. New York: W. W. Norton. Everson, S.A., Goldberg, D.E., Kaplan, G.A., Cohen, R.D., Pukkala, E., Tuomilehto, J., Salonen, J.T., & Jenkins, C.D. (1996). Hopelessness and risk of mortality and incidence of myocardial infraction and cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine, 58, 113–124. Freeman, A. (1988). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders. In C. Perris, H. Perris, & I. Blackburn (Eds.), The Theory and Practice of Cognitive Therapy. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag. Freeman, A. & Reinecke, M. (1993). Cognitive Therapy of Suicidal Behavior. New York: Springer Publishers. Freeman, A. & White, D. (1989). The treatment of suicidal behavior. In A. Freeman, K. Simon, L. Beutler, & H. Arkowitz (Eds.), Comprehensive Handbook of Cognitive Therapy. New York: Plenum Press. Freeman, A., Pretzer, J., Fleming, B., & Simon, K.M. (1990). Clinical Application of Cognitive Therapy. New York: Plenum Press. Gardner, D.L. & Cowdry, R.W. (1985). Suicidal and parasuicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 8, 389–403. Garfinkel, B. D., Froese, A. P., & Hood, J. (1982). Suicide attempts in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 139, 1257–1261. Juel-Nielsen, N. & Videbeck, T. (1970). A twin study of suicide. Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemmellologiae, 19, 307–310. Lester, D. & Beck, A.T. (1975). Suicide in the spring. Psychological Reports, 35, 893–894. Platt, J., Spivak, G., & Bloom, W. (1975). Manual for the Means Problem Solving Procedure (MEPS): A Measure for Interpersonal Problem-solving Skill. Philadelphia: Hahneman Medical College. Pokorny, A. (1960). Characteristics of forty four patients who subsequently committed suicide. Archives of General Psychiatry, 2, 314. 70 Arthur Freeman and James Jackson Reinecke, M. (1987). Advances in cognitive therapy of emotional disorders. Paper presented at the Sixth National Congress of Clinical Psychology, Santiago, Chile. Robins, E., Gassner, S., Wilkinson, R.H., & Kayes, J. (1959). Some clinical considerations in the prevention of suicide based on a study of 134 successful suicides. American Journal of Public Health, 49, 888. Rogers, S. & Luenes, A. (1979). A Psychometric and behavioral comparison of delinquents who were abused as children with nonabused peers. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35, 470–472. Rogot, E., Fabsitz, R., & Feinleib, M. (1976). Daily variations in USA mortality. American Journal of Epidemiology, 103, 198–211. Roy, A., Mazonson, A., & Pickar, D. (1984). Attempted suicide in chronic schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 303–306. Schotte, D. & Clum, D. (1987). Problem solving skills in suicidal psychiatric patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 49–54. Stein, M., Levy, M., & Glassberg, M. (1974). Separations in black and white suicide attempters. Archives of General Psychiatry, 31, 815–821. Tsuang, M. (1977). Genetic factors in suicide. Disorders of the Nervous System, 38, 498–501. Chapter 3 Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder Cory F. Newman Bipolar disorder (BD) is one of the most chronic, severe, lethal, and difficult to treat of the psychiatric disorders (Goldberg & Harrow, 1999; Goodwin & Jamison, 1990; Nilsson, 1995). In spite of the initial optimism generated by the introduction of lithium treatments in the United States in the 1970s, BD continues to subject many of its sufferers to long-term, serious dysfunction. Newer pharmacological developments, such as the use of anti-convulsants, have added helpful new dimensions to the treatment of BD (Sachs, Printz, Kahn, Carpenter, & Docherty, 2000). However, medications have not been a panacea. Some patients are refractory to medications such as lithium, carbamazepine, and valproate (Calabrese et al., 1999; Post, Leverich, Altshuler, & Mikalauskas, 1992). Others cannot tolerate the side-effects of medications, and therefore discontinue their use (Goodwin & Jamison, 1990; Jamison, Gerner, & Goodwin, 1979; Keck, McElroy, & Bennett, 1994; Ketter & Post, 1994). Still other patients are prohibited from taking these medications, due to concomitant conditions ranging from hypertension, to kidney dysfunction, to pregnancy (Chor, Mercier, & Halper, 1988; Sachs et al., 2000). Finally, many BD patients report negative feelings and attitudes regarding their medications (Newman, Leahy, Beck, Reilly-Harrington, & Gyulai, 2001; Jamison, 1995; Scott, 1996), and therefore are at constant risk of abandoning their use prematurely. Clearly, powerful psychosocial approaches are necessary as well in order to address the treatment of BD more completely. Bipolar disorder is well identified as a “diathesis-stress” disorder (Bauer & McBride, 1996; Goodwin & Jamison, 1990; Post, 1992). In other words, there are compelling data that indicate a hereditary component, leading to biochemical abnormalities that put patients at risk for the full expression of the disorder. At the same time, high genetic loading does not guarantee that a patient will develop BD. Environmental factors play a role as well, including the demands that are made upon the patient’s coping skills. Greater degrees of stress, over a more chronic course, increase the likelihood that a patient will develop the full symptomatology of BD. Therefore, one of the goals of therapy is to decrease the patient’s level of stress (Newman et al., 2001). This, by definition, will decrease the probability 72 Cory F. Newman of incurring (or recurring) the expression of the disorder. This observation leads to the following question – what is stress, and how do we reduce it? In many respects, stress is a subjective phenomenon. For example, two people are presented with an identical life problem (e.g., the loss of employment). One person views it as a catastrophic, personal failure, while the second person views it as an unfortunate situation that nevertheless presents him with an opportunity to find more suitable employment. The first person is more likely to become depressed, while the second person is more likely to maintain a high level of psychological functioning (Pretzer, Beck, & Newman, 1989). As this example illustrates, the first person’s highly negative, subjective view interacted with the situation to produce a depressive reaction. The loss of the job, in and of itself, was insufficient to cause the “stress”. However, coupled with the person’s negative, internal, global attribution, the person experienced a great deal of stress, resulting in depressive symptoms. Indeed, recent studies provide striking evidence that such attributional styles are predictive of both depressive and manic episodes (Alloy, ReillyHarrington, Fresco, Whitehouse, & Zechmeister, 1999; Reilly-Harrington, Alloy, Fresco, & Whitehouse, 1999). The above example demonstrates how a person may become depressed in the aftermath of experiencing – and negatively construing – an environmental stressor. This conceptualisation is at the heart of the theory of cognitive therapy of the emotional disorders (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979). The theory states that people who evince systematic, negative biases in their thinking processes are at risk for exaggerations and exacerbations of negative affect, such as dysphoria, anxiety, anger, and others. The risk of experiencing a clinical depression increases if this thinking style is stable over time, and if it discolours people’s views of themselves, their lives (and the world at large), and their future – the so-called “cognitive triad” (Beck et al., 1979). While this may explain the depressive phase of BD, how does it address the manic side of the equation? To begin, not all thinking that is biased is negative (Leahy & Beck, 1988; Leahy, 1999). As we will see, thinking that is excessively expansive, and grandiose, as it often is in people who are hypomanic, is problematic as well. Such thinking can induce people to engage in undercontrolled activities, such as overspending, imprudent sexual behaviour, and impulsive decision-making, that serve to create problems for these people. This, in turn, puts more demands on their lives. As the negative consequences accumulate, the need for advanced problem-solving exceeds the hypomanic person’s ability to cope. Often, this then leads to a marked depressive episode, as the person recognises the disturbing fallout of his or her undercontrolled behaviour. Clearly, a person in this situation needs to be at his or her best in order to deal effectively with many real-life problems. However, a BD patient who is depressed typically will feel lethargic, and hopeless, and will be in a poor position to do good problem-solving. The result is that the problems will continue Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder 73 to grow, and the BD patient’s overall levels of stress – both actual and perceived – will not diminish. As noted above, an efficacious psychosocial therapy for BD must help patients to decrease their stress (Basco & Rush, 1996). Additionally, stress can be a physiological factor. For example, people who maintain erratic sleep–wake patterns place a burden on the functioning of their organ systems, including the central nervous system. Similarly, people who abuse substances (e.g., alcohol, stimulants, analgesics), or who engage in suboptimal eating patterns, disrupt normal biochemical homeostasis. Patients who suffer from BD are especially prone to such disruptions of physiological functioning, and therefore are at risk of perpetuating a vicious cycle of behavioural and biochemical dyscontrol (Basco & Rush, 1996: Bauer & McBride, 1996). Therefore, part of the role of a psychosocial therapy is to teach patients to regulate their sleeping, eating, patterns of activity, and ingestion of psychoactive substances (Ehlers, Kupfer, Frank, & Monk, 1993; Tohen & Zarate, 1999). If successful, this approach will reduce stress as well. Basic goals of cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder As described above, cognitive therapy (CT) is especially well-suited to help patients decrease their subjective (and physiological) levels of stress, thus decreasing the probability of their experiencing full-blown, uncontrolled, affective cycling. This overarching goal can be accomplished via the following tasks. Therapists should: 1 2 3 4 5 Educate patients about their bipolar illness. Help them to understand the aetiology, and course of the disorder. Give them information that will help them to make informed, practical decisions about their treatment. Explain their role in helping themselves to combat the disorder, to increase their sense of empowerment. Test the reality of patients’ thinking. Show patients how they may monitor their own thinking, so that they may keep it within normal limits. Give them exercises that will assist them in reconstruing thoughts that are either too pessimistic, or too positively inflated. Instruct patients in the principles and practices of problem-solving, so that they may effectively address the actual problems that they otherwise may neglect, or exacerbate. Control a patient’s tendency to be reckless and impulsive when hypomanic. Give tactful, corrective feedback about their behaviour in session. Help patients to perform techniques of self-monitoring between sessions. Explain the rationale for – and benefits of – self-restraint, patience, and reflective delay. Modulate the patient’s expressions of affect, through modelling, roleplaying, audio-video feedback, relaxation, and other techniques. 74 Cory F. Newman 6 Counteract the patient’s disorganisation and distractibility by using strategies that maximise planning, focusing, and repetition. These are ambitious goals, but it is just such a broad range of aims that are necessary in order to address a disorder of the magnitude of BD. In the following sections, further details about each of the six aims are provided. Most of the focus will be on hypomania, and mania, as there is a wealth of literature on CT for depression that need not be reproduced at length in the present chapter. Educate the patient The more that BD patients know about their disorder, the better they will be able to serve as collaborators in their treatment. For example, a patient who understands that BD is a chronic disorder that can be managed, but perhaps not cured, will be more likely to remain faithful to their therapeutic plan (including medication), even if they feel well, and normal. This will reduce the chance of relapse that is induced by patients’ impulsive abandonment of treatment. By the same token, they will be less apt to feel demoralised and hopeless when symptoms recur. They will understand that this does not mean that all treatment is useless, and that they are inevitably trapped in a life filled with suffering. Instead, the patients will be ready to apply a wide range of techniques in response to an unfortunate appearance of symptoms that cannot always be predicted. It is very important for patients to learn about the influence of sleeping, eating, and activity patterns on their moods. These are some of the “zeitgebers”, or time-givers (Ehlers et al., 1993), that regulate people’s overall levels of functioning. BD patients are extremely sensitive to disruptions in sleep, eating, and activity level, and irregularities in these areas can produce biochemical changes that are associated with mood swings (Basco & Rush, 1996). For example, BD patients need to be instructed to take great care about adjusting to “jet lag” when their travels take them across multiple time zones. Similarly, therapists must discourage their BD patients from volunteering for jobs that involve rotating shifts, and conversely support their BD patients’ efforts at keeping their work schedules stable. In general, therapists greatly help their BD patients when they help them to achieve greater levels of constancy, stability, and predictability in their basic, daily functioning. Therapists and BD patients should attempt to ascertain the “early warning signs” of the patients’ problematic mood shifts (Lam, Jones, Hayward, & Bright, 1999; Lam & Wong, 1997). Patients often report that it is exceedingly difficult to apply the self-help, self-correcting techniques of CT (e.g., Greenberger & Padesky, 1995) once they are fully immersed in a manic state. However, they note that they can help themselves if they “catch themselves” in the early stages of hypomania. Clearly, self-awareness is of paramount importance. For example, one of the author’s patients noted that her Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder 75 increased irritability was one of her chief warning signs of an impending manic episode. When she would get angry, she would sit down, engage in relaxation exercises, and either read or listen to chamber music. Another patient ascertained that an early warning sign of mania was his having sexual fantasies about many different women. As he stated, “If I can’t even hear what a woman is trying to say to me, because I’m thinking about making love to her, I know I have to slow myself down immediately.” This same patient also offered that an “absence of anxiety” signalled an impending manic episode. At such times, he would try to focus his attention on his responsibilities and tasks, such as the upcoming deadline on his thesis. His goal was to increase his anxiety just enough to care about attending to his work. Another aspect of educating the patient involves a discussion of the differences between “normal good mood” and hypomania. We, as clinicians, do not want BD patients to come to distrust and fear their own pleasant moods. This undesirable outcome would lead BD patients to feel troubled, no matter what their actual condition. Instead, we want to help BD patients systematically to differentiate between “healthy” affect and “inflated” affect. The following are some of the criteria that the author and his BD patients have generated as indicative of “healthy, positive” affect: • • • • • • • • • The patient’s good mood is congruent with the situation, including the moods of others in the immediate environment. The patient is able to engage in an enjoyable activity, without being unduly distracted or beckoned by other activities. The patient is able to sit comfortably, relax, and engage in sedate conversation with others, without experiencing boredom, or pronounced urges to spring into action. The patient is able to read at length if alone, and able to listen intently to others if he or she is in their company. Focused concentration is readily achieved. The patient is content with a trouble-free situation, and does not feel a strong impulse to “stir up trouble” in order to create stimulation. The patient can successfully balance work and play, without becoming totally absorbed in one, at the expense of the other. The patient’s good moods do not prevent him or her from falling asleep at night. The patient can exercise good social judgement, such as refraining from telephoning a friend very late at night in order to tell him a “great new idea”. The patient’s good mood does not stop him or her from remembering lessons that were learned during moments of distress, and strife. Therefore, the patient remains aware of the actual benefits and consequences of a full range of behaviours, and chooses to engage in behaviours in a wise fashion. 76 Cory F. Newman • The patient does not increase his or her use of chemical substances, including nicotine, alcohol, stimulants, analgesics, hallucinogens, and others. The patient does not dwell on suicide, and does not romanticise death. The patient is able to accept constructive criticism without become highly irritated. The patient can exercise patience, and can delay gratification. • • • When BD patients notice that their elevated moods fail to meet many of the above criteria, this serves as a further “early warning sign”, and signifies the need to utilise CT self-help interventions (to be described throughout this chapter). A most important part of educating BD patients involves the utilisation of their own life experience. By the time that most BD patients present for treatment, they have experienced many, serious consequences as a result of their erratic moods, thoughts, and behaviours. This is unfortunate in its own right. However, these experiences all too often fail to serve the purpose of helping BD patients to make reparative corrections in their lives. Instead, they tend to induce a sense of hopelessness and shame in BD sufferers at the one extreme, and minimisation and denial at the other extreme. Without a doubt, the former problem exacerbates a patient’s dysphoria, while the latter problem puts the patient at risk for repeating old mistakes. Therefore, it is useful for therapists to show respect for their BD patients’ life experiences, especially the negative ones. Rather than risk insulting, or patronising, a patient by saying, “Now, now, Mr. Smith, you cannot go on that adventure holiday; after all, don’t you remember the disaster you created the last time you took such a trip?”, instead, the therapist must encourage the patient to demonstrate caution by appealing to the patient’s own recollections. For example, the therapist can say, “I know that you would greatly enjoy taking that trip to the Himalayas, and I am certainly in favour of your having a high quality of life. However, Mr. Smith, in your valuable, personal experience, have you learned reasons why it might be a good idea to postpone this trip, or at least to modify it somewhat?” If the patient is not able to remember the negative consequences that occurred in similar, past situations, the therapist can provide a prompt, such as, “Is this vacation plan similar to the trip you took in 1992, when you spent all your money, and then got lost in the wilderness for four days? How can you safeguard yourself against such a traumatic outcome now, and in the future?” The goal is to tactfully help BD patients to focus on the potential, negative consequences of some of their more grandiose plans. The ability to weigh pros and cons, to anticipate problems, and to be flexible in making plans, are among the most important skills of the mentally healthy person. The CT therapist should help their BD patients to practise these skills, with the “raw data” coming from the patient’s own natural education in life. Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder 77 Finally, bibliotherapy can be most helpful as an adjunct to the work of CT. Patients benefit by reading some of the popular (as well as professional) literature on BD. Books such as Fieve’s Moodswing (1975), and Jamison’s An Unquiet Mind (1995) are worth their weight in gold in terms of teaching BD sufferers about their disorder in a compassionate, informed, cost-effective manner. Therapists can maximise the benefits of sources such as these by reading these books themselves, and discussing their contents with BD patients as part of the therapy session. This will facilitate the sense of collaboration between patient and therapist, and will assist the therapist in correcting any misinterpretations that patients may be making about the contents of the literature. Likewise, the families of bipolar patients can take part in learning about their family member’s problems. For example, therapists can distribute and discuss the authoritative guidebook published by Kahn, Ross, Printz, and Sachs (2000), which spells out in clear, everyday language how bipolar disorder manifests itself, and how it can be treated. When patients and their families can communicate more knowledgeably and effectively, the likelihood of both discord in the household and exacerbation of the patients’ symptoms can be reduced (Miklowitz & Goldstein, 1997). Test the reality of the patient’s hyper-positive thinking When therapists notice in session (or on the phone) that their BD patients are showing signs of expansive, or grandiose thinking, they have an important responsibility to help the patients to evaluate their thinking. Understandably, therapists may be loath to question their patients’ good moods, enthusiasm, and active behavioural plans, especially in the aftermath of a depressive phase. Therapists may be concerned that the patients will feel invalidated, or punished for their “positive” behaviour, and that this will damage the therapeutic relationship. Therefore, therapists may give their hypomanic patients insufficient feedback, and the early warning signs of mania will be ignored. In spite of these concerns, therapists do more harm than good if they remain passive in such instances. Instead, therapists must find a gentle, tactful way to address the patients’ potentially problematic thinking. A useful method to accomplish the above goal is essentially the same method that therapists use to challenge negatively biased thinking – Socratic questioning (Overholser, 1988). The use of the Socratic method accomplishes a number of useful goals. First, it minimises the likelihood that the hypomanic patients will believe that their therapists are trying to control their behaviour. This will diminish the probability that the patients will rebel against the therapist’s suggestions. Second, the method shows respect for the patients’ thinking, and reasoning skills. Socratic questioning does not dictate to the patients. Rather, it asks them to ponder, and consider a wide range of evidence, and alternatives. Third, Socratic questioning helps patients to stop 78 Cory F. Newman and think, instead of acting on impulse. Finally, Socratic questions may help patients to arrive at their own conclusions, which will boost their self-efficacy in a more enduring fashion than if the patients simply rely on the therapists’ opinions. For example, one of the author’s BD patients stated that she wished to start her own marketing business. This patient, who had recently been depressed and suicidal, was now brimming with confidence and enthusiasm. However, the therapist knew that this patient did not have sufficient money, and other resources, to start her own business. Instead, it would be much more prudent for this patient to work for an employer, and to earn a stable salary. The therapist did not wish to criticise the patient’s thinking, as he was concerned that she would feel unsupported, and become angry and defiant. At the same time, the therapist understood that it was of critical importance to help this patient to think through her decisions very carefully before acting. Therefore, instead of saying, “Emily, I do not think it is wise for you to invest in your own business; you should work for someone else”, the therapist used a series of Socratic questions. For example, he asked Emily (with a positive tone): I can see that you are very happy with this idea. Do you have all of the financial details worked out in advance? Who are the consultants and advisers that you have chosen? Do they have some good ideas that you can use? How much money will you need to borrow in order to start your business? Are you eligible for a business loan? Do you believe that you are in a position to take this risk? What are the pros and cons of having your own business, as opposed to working for someone else? What have you concluded about this basic question? By asking these questions in a respectful manner, the therapist succeeded in getting Emily to discuss the relevant issues, before acting. Emily acknowledged that she did not have any advisers, and wondered if she should talk to other people in the business world first. Emily admitted that she had not yet determined how much money she would need, and that she had not considered whether or not she was eligible for a loan. She added that she had not weighed the pros and cons of being her own boss, versus working for someone else. Emily was able to conclude – for herself – that her original plans needed to be revised. Although she was not willing to abandon the notion of having a business of her own, Emily did state that she would need to minimise her costs, and that she may have to work for someone else first, in order to begin saving money. A related technique is the Devil’s advocacy role-play. When the therapist notes that the BD patient’s ideas are becoming too extreme, yet are resistant to modification, the therapist introduces the following challenge. The therapist Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder 79 and patient will engage in a friendly debate about the matter, with the therapist taking the patient’s position, and the patient taking the more conservative position. At first, some BD patients may decline to take part in this exercise, reasoning that they do not wish to argue against their actual viewpoint. However, the therapist can make the exercise more attractive by reminding the patient that “it is the mark of a sharp mind, and the essence of an expert debater, to be able to convincingly argue the merits of any issue, whether you believe it or not”. As an illustration, “Lanny”, a college student, tended to neglect his studies when he became hypomanic. He reasoned that it was more important to spend all of his time talking about philosophical issues with his friends in the dormitory, rather than read and write by himself. As a result, he was in danger of failing two of his courses. Lanny stated that he did not care if he failed, because he was “getting an education in life, and that is all that really matters”. The therapist persuaded Lanny to take part in a Devil’s advocacy role-play, where Lanny had to argue the benefits of studying, and the therapist took the position that talking with friends was more important. The role-play was very spirited, and both parties were amused (which solidified the therapeutic bond between them). When the role-play concluded, the therapist asked Lanny what he had learned. To summarise, Lanny learned that: (1) it is possible to talk to friends, and still leave sufficient time to study for courses, (2) receiving passing grades actually is very important, because it is a means to an end – a college degree, with all of the practical benefits that go with it, (3) the therapist truly understood him, because he debated Lanny’s position so well, and (4) he may be bothering other people when they are trying to study; therefore it is in Lanny’s best interest to leave them alone more often. It is critically important for BD patients to learn to self-monitor and test their hyper-positive thinking in everyday life, when the therapist is not there to provide feedback. Here, the therapist’s role is to prepare and prompt the patients to exercise caution in their day-to-day decision-making. For example, therapists teach their BD patients that they will benefit greatly by consulting with others, prior to enacting plans. The author recommends that his BD patients seek the advice and feedback of at least two others, one of whom may be the therapist. Therefore, if a BD patient suddenly gets the idea that he wants to buy a new car, he may choose to speak with his wife, and his brother (and others of his choosing), before following through with the purchase. When the therapist teaches BD patients this technique, the therapist must bear in mind that BD patients are very sensitive to issues of interpersonal control (Newman et al., 2001). Therefore, the manner in which the therapist presents this procedure is critical to its success. If the therapist implies that the BD patient is incapable of making his or her own decisions, the patient will probably resist, and will not use the technique. On the other hand, the therapist can support the BD patient’s somewhat fragile self-esteem (Winters 80 Cory F. Newman & Neale, 1985) by noting that “all of the world’s most influential and powerful people have a team of advisers, because they are smart enough to make use of all of their external resources, including the valuable feedback of esteemed others”. This conceptualisation of the benefits of consulting with others is more palatable to BD patients who might otherwise seek complete autonomy, to their detriment. Therapists also ask their BD patients to practise filling out Daily Thought Records1 (DTRs: Beck et al., 1979) between sessions, as part of their cognitive therapy homework. In the same way that depressed patients are taught to spot all-or-none thinking, overgeneralisation, fortune-telling, and the like, hypomanic patients are instructed to monitor distortions in their thinking processes. For example, BD patients may become angry when they assume that other people are deliberately denying them what they want. This is the cognitive distortion of “mind-reading” (Burns, 1980). In order to change this attribution, and perhaps diminish their anger, the BD patients can complete a DTR that addresses this scenario. In a similar vein, a BD patient may disqualify the negative (the polar opposite of the depressive process of disqualifying the positive), as Lanny had done when he claimed failing his college courses was of no consequence to him. Using a DTR, this patient can remind himself of the negative consequences of his intended actions, and thus give himself the opportunity to change his behavioural strategy, before he actually fails. Problem-solving A vital part of the strategy to reduce the BD patients’ levels of stress is to teach them to become more effective problem-solvers (Basco & Rush, 1996). It is a truism that all people face problems in life, but the more successful, happy people are those who skilfully and promptly deal with their problems. This notion takes on added significance for people who suffer from BD. When BD patients experience difficulties in their lives, they are at risk for incurring mood abnormalities. It is often the case that BD patients will report retrospectively that previous manic or depressive episodes seemed to be triggered by negative events (or series of such events) in their lives. Similarly, major life changes can tax a patient’s ability to cope, and may signal the start of a mood swing (Johnson & Roberts, 1995). Common, major stressors of this sort include: (1) death of a friend or family member, (2) pregnancy and childbirth, (3) starting school, (4) changing jobs, (5) moving to a new 1 Beck et al. (1979) originally called these forms “Daily Records of Dysfunctional Thoughts”. Later, the term was shortened in practice to “Dysfunctional Thought Records”. The author prefers to call them “Daily Thought Records”, as this designation may be seen by patients as potentially less pejorative, while still maintaining the recognisable acronym of “DTR”. Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder 81 geographic location, (6) financial setbacks, (7) medical illness, and (8) relationship discord and divorce. It is not only the case that major life stressors can induce the onset of severe mood disturbances in BD patients. It is also likely that the BD patient’s erratic behaviours will result in further serious problems. When patients act with manic recklessness, they often incur numerous difficulties in their relationships, their work, their health, and other major life areas. These additional problems will further strain the BD patient’s ability to cope. Often the patient’s condition worsens, and spirals downward as moods, behaviours, and problems become exacerbated by each other. Clearly, BD patients who practise and refine their problem-solving skills will be in a much better position to weather times of strife in their lives. Therefore, they may avert the onset of manic or depressive recurrence. Further, by utilising good problem-solving skills, BD patients can prevent downward spirals that otherwise are common in patients who neglect or add to their problems. BD patients are in the best position to learn, and execute effective problemsolving when they are in euthymic mood states. Therefore, it is important for therapists to seize the opportunity provided by the BD patients’ quiescent times in order to teach them the principles of problem-solving. Along similar lines, it is important for therapists to recognise when hypomanic patients are getting themselves into troublesome situations (e.g., spending too much money on unnecessary things), and to help the patients contain and limit the problems before they worsen. The process of teaching BD patients to do comprehensive problem-solving involves the following components. Therapists should: 1 2 3 4 5 Assist the patients in studying their past crises; how they started, how they became difficult to manage, and what the patients could have done differently in order to prevent, or limit their occurrence. Give patients the assignment of setting short-term goals in major life areas, such as work, relationships, and self-improvement; and show them how to monitor their progress across these domains on a regular basis. Brainstorm the steps that are necessary in order to achieve the above goals. Identify potential complications or obstacles to taking the above steps. Teach the patients such fundamental techniques as defining their problems, generating potential solutions, evaluating the pros and cons of each proposed solution, choosing the most advantageous (often the most conservative) of these solutions, acting on the solution in a prompt fashion, and monitoring the outcome, so that the patient can make changes, if necessary (Nezu, Nezu, & Perri, 1989). In order for BD patients to make the best use of problem-solving skills, they must avoid having an all-or-nothing attitude (a form of biased thinking that 82 Cory F. Newman is common in affective disorders). For example, it is dysfunctional for patients to believe that they have no problems that require their attention. This attitude bespeaks hypomanic overconfidence, often leading to lack of vigilance, and a problematic absence of self-monitoring. At the opposite extreme, it is harmful if BD patients become so discouraged by their problems that they conclude that “there is nothing I can do, so I might as well give up (or keep adding to my problems, because I don’t care anymore)”. This attitude puts patients at risk for getting into downward spirals, exacerbating the risk of suicide (Ellis & Newman, 1996; Newman, in press). Therefore, it is extremely important for therapists to assist their BD patients in seeing the benefits of a “middle-ground” approach to problemsolving. In this mindset, the patients always look for potential problems before they act, they take pride in their ability to self-monitor, and understand the benefits of “damage control”. As the author tells his patients, “It is almost never too late to try to correct a problem, and it is almost always beneficial to care enough about what will happen to you, so that you change your behaviour.” Control impulsivity and recklessness Patients who are hypomanic, or who are in the early stages of a full-blown manic episode, often feel exuberant and “spontaneous”. They feel driven to act on their feelings and impulses, without thinking things through carefully. This can lead to unwise or dangerous behaviours that the patients (and/or the patients’ loved ones) later regret (Jamison, 1995). Therefore, it is useful for therapists to collaborate with their BD patients to utilise techniques that provide them with time to reflect, and benign restrictions (it is necessary that the restrictions be “benign,” otherwise the BD patients may resist the technique in order to maintain their sense of autonomy and control). One such technique instructs BD patients to list their own “wise sayings” on flashcards. These “wise sayings” are recommendations to engage in careful, methodical, conservative behaviour, especially under conditions in which the patients have an urge to do something highly stimulating. Patients keep these flashcards in convenient locations for easy access, such as tacked on the refrigerator, in their wallet or handbag, taped under the bathroom mirror, propped up beside the alarm clock, or in the glove compartment of the car. Some of the “wise sayings” that the author’s BD patients have generated include the following: • • I can be in greater control of a situation if I think things through slowly and carefully. Don’t get into conflicts with people. Just walk away. I will keep my dignity that way. Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder • • • 83 It is smart to consult with other people. I shouldn’t make snap decisions on my own. Do one thing at a time. Don’t try to do everything. Proceed step by step. Always think of the potential consequences. Don’t try to be Superman. Patients are more receptive to these constraints when they are self-generated, as compared to when other people tell them what to do. A simple behavioural technique, called the “48 hour waiting period” rule, is based on the principle that one should not enact any big, life decisions if one is in a very aroused state, whether positive or negative. For example, it is unwise to gamble large sums of money, based on “feeling lucky tonight”. Similarly, it is self-defeating to drop out of school in reaction to disappointment with a test grade. Therapists ask their patients to keep a logbook of the day and times when they wish to do something that is “bold, risky, wild, extraordinarily funfilled, or involves a major life change (such as quitting a job, or proposing marriage)”. Then, they are to wait at least two full days (including at least one full night of sleep) before acting on this wish. The rationale is as follows: if the patient’s ideas and plans are good, they will still be good after the passage of two days. Nothing will be lost by waiting. On the other hand, if the ideas and plans are flawed, this may become apparent to the patient during the waiting period, and the patient can abandon his or her intentions before harm is done. Therapists should emphasise that this technique requires “uncommon patience and foresight”, and that only very few patients can succeed in utilising this technique optimally. Aside from being a statement of fact, it also sets up the sort of challenge that many hypomanic patients are eager to accept, if for no other reason than to prove their special abilities. Therapists also may choose to instruct their patients to use the 48 hour waiting period as an excellent opportunity in which to consult with others about their ideas and plans. A very simple, but effective technique asks patients to do more sitting and listening, and less standing and talking. This behavioural manœuvre should be applied to social situations in which the BD patients notice that they are speaking or gesticulating rapidly. The intention is to interrupt the patients’ overactivated sympathetic nervous system activity, along with its concomitant rapid, energetic behaviour. By silently reminding themselves to sit down, and to listen more intently to others, BD patients can decrease the risk of acting in socially inappropriate ways. Further, the technique orients patients to attend more to their environment, and less to their own racing thoughts. In order to facilitate their using the above strategy, patients can practise the use of covert self-instruction. Examples include the patients telling themselves to: 84 Cory F. Newman • • Pay attention. Listen to [other person’s name in the social situation]. Recognise that this is a meaningful conversation. Don’t miss hearing anything. Be a good friend. Be quietly supportive. Let the other person have the “stage”. I will be noble and altruistic. • • Recklessness and impulsivity also can be reduced via the use of Daily Activity Schedules (DAS; see Beck et al., 1979). By planning their schedules, and respecting the importance of adhering to the schedule, BD patients are less likely to do “spur of the moment” things. This strategy encourages the patient to be more systematic and methodical. It can be extremely beneficial for BD patients to lower the level of unpredictability in their daily lives. An important caveat about the use of the DAS: hypomanic and manic patients tend to be overactive (Bauer, Crits-Christoph, Ball et al., 1991). Therefore, they may misuse the DAS to schedule too many activities, thus driving them to exacerbate their symptoms (e.g., via not getting enough sleep). To safeguard against this, therapists can ask the patients to prioritise their activities (Palmer, Williams, & Adams, 1995), and to identify the “20% or 30% of the activities that you can strike off your schedule, with little consequence”. The author exhorts his BD patients to heed the words of the great early American statesman (and founder of the University of Pennsylvania) Benjamin Franklin, who extolled the virtues of doing “all things in moderation”. Additionally, it is wise to make arrangements in the BD patients’ lives that make it inconvenient for them to enact risky behaviours. This tactic is a form of the behavioural strategy known as “stimulus control”. Again, there is a much greater chance that the patients will comply with this method if they actively participate in its planning. Similar to patients who are prone to substance abuse (Beck, Wright, Newman, & Liese, 1993) – and, in fact, many BD patients experience this problem as well (Bauer & McBride, 1996; Tohen & Zarate, 1999) – BD patients have “high risk situations” that are associated with manic behaviours. In addition to the abuse of alcohol and substances (which ideally should not be kept in the household of a BP sufferer), typical high risk situations include: • • • • places where large sums of money can be spent, such as upscale restaurants, casinos, expensive boutiques, race tracks, auto dealerships, malls, etc., activities that entail the use of weapons, such as hunting, target shooting, recreational explosives (also known as “fireworks”), etc., socialising with people who are stimulation-seekers, and/or who have a personal history of associating with the BD patient in risky activities (e.g., former extramarital lover, drug cohorts, gambling buddies, etc.), and work situations that require the BD patient to push the limits of endurance, and therefore disrupt sleep–wake cycles, eating patterns, and induce driven behaviours. Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder 85 These are but a few of the most common classes of high-risk situations. Others include jet travel across multiple time zones, recreational pursuits that produce “rushes” of excitement (e.g., rock climbing, skydiving, and other activities popularly known in the United States as “extreme sports”), nightclubs, and any social event that encourages the person to try to become the centre of attention. Therapists and their BD patients generate lists of the above high-risk situations, as well as others that may be more idiosyncratic to the individual patient. Then, the patients make a verbal contract to voluntarily refrain from seeking out such situations, or purposely remaining in such situations. Alternatively, BD patients may promise to take part in these activities only when in the presence of a trusted companion, such as going to the mall with a spouse. Then, as a sign of good will, and empathy, the therapist helps the BD patient to discover substitute activities that the patient will enjoy, but that entail far less risk. Affect modulation In the same manner that panic disorder patients benefit from learning to control their breathing (Clark, Salkovskis, & Chalkley, 1985), hypomanic and manic patients can modulate their high affect by decreasing their rate, and volume of breathing. This technique is most effective when used in combination with relaxation exercises. Therapists teach their BD patients to spot their intense emotionality as a cue to sit down, close their eyes, and to breathe slowly, smoothly, but not deeply. Unless they are in conspicuous social situations that make the technique impractical, BD patients then can proceed to implement the “tense and relax” procedures of Jacobsonian relaxation (see Goldfried & Davison, 1976, chapter 5, pp. 81–111). Here, patients systematically go through the various muscle groups in their body, tensing or flexing them for five seconds, then releasing, one group at a time. The resulting sense of contrast accentuates the perception of relaxation, and lowers overall arousal. A very basic way that therapists can help their BD patients to keep their moods and behaviours within normal limits is to model a moderate level of energy and emotionality. If a BD patient becomes overly animated, or excessively irritable in session, it is vitally important for the therapist not to respond in kind. Instead, the therapist must maintain a calm, pleasant, levelheaded approach. Therapists who demonstrate a strong, caring, dignified demeanour serve as the best calming influence. When BD patients feel a sense of inflated energy, and euphoria, they find it difficult to demonstrate patience. Instead, they often exhibit low frustration tolerance when they are blocked from doing what they wish. Therapists can discourage their BD patients from acting on impulse by noting that it requires great skill and maturity to wait for what they want. Similarly, it is often quite 86 Cory F. Newman noble to make sacrifices, and to experience a sense of deprivation. In this manner, the therapist reframes the BD patient’s acceptance of the inevitability of frustration as a sign of high level functioning. Self-statements that include “shoulds” and “musts” sometimes drive impulsive behaviour. For example, the patient may think, “I should be allowed to control my own life”, “I must get everything done as soon as possible in order to feel relief from this tension”, or “I should get what I need right away”. Therapists can teach their BD patients to self-monitor their sense of frustration, and desires to act impulsively, and to ask themselves, “What ‘should statement’ am I thinking right now?” The patient is instructed to formulate a rational response that runs counter to the “should statement”, such as “I would like to control my own life, but sometimes this entails being cautious, and listening to the advice of people who care about me.” Ideally, the patient will write down these rational responses, for long-term reference. Sometimes BD patients act out in response to extremely intense emotions, regardless of how unstable, and unrepresentative those emotions may be. For example, they may angrily assail someone in public, even though they generally have a high regard for that person. Similarly, they may become involved in an illicit sexual relationship, based on a momentary surge of feelings after a warm conversation with someone. As a result, BD patients are prone to regret that they acted on their feelings. In order to reduce the likelihood of these unfortunate scenarios, therapists instruct their BD patients to monitor the longevity of their feelings, and to compare this with the intensity of their feelings. The following guideline is applied: act on the emotions on the basis of their longevity, not the intensity. Therefore, if the strong feelings are fleeting, the BD patient will not act in a way that brings regret later. If the feelings are long-lasting, then the patient must still consider the pros and cons of expressing these feelings openly. Therapists validate their patients’ feelings, but recommend that patients act on these feelings only after evaluating their staying power, as well as the pros and cons of expressing them. Counteracting disorganisation and distractibility Many BD patients evidence markedly unfocused thinking (Goodwin & Jamison, 1990). This is typified by flights of ideas and speech, difficulty in answering direct questions with direct answers, and a propensity for starting and discontinuing personal projects and therapy homework alike. Therapists witness these symptoms in their BD patients when they fail to follow session agendas, show deficits in their ability to understand what their therapists are saying, and remember very little of the contents of the therapy sessions once they leave the office. To some degree, the structure of a cognitive therapy session helps the BD patients to stay reasonably on task. For example, therapists use periodic Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder 87 summary statements, highlight and repeat their main points, and frequently ask for feedback to check for the patients’ understanding. Additionally, some benefits are achieved through medications. However, these factors are not always sufficient to help BD patients maintain their concentration and focus. Therefore, it is wise for BD patients to take notes while they are in session, and to make audiotaped recordings of their sessions, so that they may listen again later. In everyday life, BD patients can practise the skill of completing one task before starting another, and can spend a good deal of time writing as part of their therapy homework. Additionally, BD patients should be advised to make activity schedules, lists of important tasks, and to make use of planning and problem-solving as often as possible. Sometimes, the simple act of slowing down may help patients to be less distractible. This will help patients to process information more effectively, thus helping them in their social interactions, and their work-related tasks. Further, their self-esteem will be enhanced as well. Special considerations in the treatment of bipolar disorder Conceptualisation of the individual patient The symptoms of mania often are so marked, and so difficult to manage clinically, that there is a tendency for clinicians to focus on the disorder, but to neglect to understand the individual patient. While it certainly is important to practise the general strategies of “mania management” – indeed, the entire chapter to this point has outlined such global techniques – it is vital to formulate a conceptualisation of each patient (J.S. Beck, 1995; Needleman, 1999). One of the most basic, and useful, methods of cognitive case conceptualisation is the cognitive triad (Beck et al., 1979). This comprises the patient’s beliefs about: (1) him- or herself, (2) others, the world, and life in general, and (3) the future. Therapists can ascertain their patients’ beliefs in these three important domains via a number of simple methods: • • • • • direct questioning, homework assignments that ask the patients to write short essays about their views of themselves, their lives, and their futures, taking a personal (and psychiatric) history of the patient, and generating hypotheses about “what life experience has taught the patient to believe”, generating hypotheses about the patients’ beliefs based on their spontaneous comments in session, and generating hypotheses about the patients’ beliefs based on the nature and quality of the therapeutic relationship. 88 Cory F. Newman When therapists attempt to understand the patients’ individual life experiences, and concomitant belief systems, they are in a much better position to form a positive, working alliance with their patients. Therapists who conceptualise each patient have the best chance of demonstrating accurate empathy, and the patients will be more apt to feel understood. The resultant strengthening of the therapeutic bond will increase the chance that the BD patient will engage more effectively in the therapeutic process (Newman, 1994). It will also decrease the chance that a temporary misunderstanding between the therapist and patient will result in a damaging rupture in the alliance. To illustrate the importance of individual case conceptualisation, let us consider the following two BD patients. “Valery” is a 40-year-old married, mother of three children, and “Lanny” is a 22-year-old college student. Both patients evidence marked irritability, difficulty concentrating, impulsive behaviour, and hopelessness about the future. These characteristics represent the similarities between the two patients, based on their shared diagnosis. However, there are important differences between them that must be ascertained through individual case conceptualisation, in order to fit the treatment in specific ways to each patient. For example, Valery views herself as a “weak” person who is too easily controlled by others. Her anger becomes more pronounced as she feels more and more helpless. She views other people as malevolent, and therefore she distrusts them. Because she believes she cannot assert herself, Valery attempts to gain control by being passive–aggressive. This causes others, including her husband, to exert greater control over Valery’s behaviour, which “confirms” her belief that she is weak, and that others are malevolent. In explaining why she sometimes wished that she could be left alone for ever, Valery stated the following personal credo – “no people equals no problems”. Valery’s views took on added significance when the therapist learned (through taking a psychiatric history) that Valery had been sexually abused by her grandfather. Indeed, this traumatic experience made her feel weak and helpless, influenced her to distrust others, and inspired her to wish to be left entirely alone. By understanding these experiences and views, Valery’s therapist was able to show accurate empathy for her position. He was able to validate her anger, her desire for a large amount of personal space, and her impulse to want to leave therapy altogether. This approach somewhat reduced Valery’s mistrust, helped her to feel more comfortable, increased her level of hope, and concomitantly led her to be more vigilant in taking her medications. By contrast, Lanny’s irritability was based on feeling thwarted in accomplishing his goals. He believed that he had special abilities that were unappreciated by others. Furthermore, he believed that others were jealous of him, and therefore were trying to prevent him from succeeding in life. His hopelessness was based on the belief that he was destined to be one of the “geniuses whose spirit is crushed by the ignorance of others”. Lanny cited a number of famous people who had become embittered by the hardships of Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder 89 life, and who had ultimately committed suicide, and he hinted that a similar fate would be in store for him. This belief system made sense in the context of Lanny’s history, in which he was the only child of a father who suffered from BD, and a mother who fought with recurrent depression. Lanny was given a tremendous amount of conflicting information by his parents. On the one hand, they could be extremely supportive, telling Lanny that he could do no wrong. On the other hand, they could be neglectful, inasmuch as they were dealing with their own, serious affective disorders. Therefore, Lanny felt very special, but absent of guidance to help him succeed in life. This contributed to his agitation, and insecurity. Further, Lanny witnessed his parents’ failures to achieve their goals, and saw how they had become cynical. Lanny wished to succeed where they had failed, but he could not shake the belief that he would become exactly like them, and that the future held little promise for any of them. This knowledge about Lanny helped guide the therapist in taking a therapeutic stance that was tailor-made for him. The therapist knew that he would have to help Lanny curb his impulsive behaviour, but was very careful not to reinforce Lanny’s belief that he was being thwarted once again. The therapist often asked for feedback, to determine whether Lanny felt he was being sufficiently supported by the therapist. The therapist attempted to provide Lanny with the sort of explicit advice that he had not received from his parents; but the therapist balanced this approach with Socratic questioning, so that Lanny could learn to problem-solve for himself. In addition, the therapist encouraged Lanny to “slow down, so that you do not burn out like a shooting star, and so you may have a more secure future”. This led to therapeutic discussions about how to strive for long-term goals, and how to remain hopeful in spite of temporary hardships. Making peace with psychotropic medications BD entails a biochemical abnormality, therefore medication is a vital part of the treatment regimen (unless specifically contraindicated, as in the event of renal dysfunction). However, it is a fact of clinical life that BD patients often have difficulties in maintaining a steady, vigilant, long-term compliance with their pharmacotherapy (Cochran, 1984; Goodwin & Jamison, 1990; Jamison, 1995; Jamison & Akiskal, 1983). There are many reasons why patients experience this difficulty. Some of the reasons are a matter of practicality. For example, some medication regimens (e.g., those that involve multiple agents, and multiple daily dosages) require the patient to demonstrate high levels of concentration, self-monitoring, and routinisation. Unfortunately, these are among the very cognitive skills with which BD sufferers have the most trouble. Therefore the cognitive therapist must assist the BD patient in learning and utilising the skills of planning, cueing, scheduling, and self-instruction (Wright & Schrodt, 1988). For 90 Cory F. Newman example, one of the BD patient’s homework assignments can be to design and construct a written chart, on which he or she will record the times and dosages of the relevant medications. Then, the patient marks a “check” next to each item when the medication is taken successfully. If the patient is willing to accept reminders from loved ones, therapists can instruct the patient’s family to assist in monitoring the patient’s consistency in taking the medications. This must be handled with care, as BD patients often perceive their family as excessively intrusive in matters such as this. Another set of reasons for insufficient compliance with pharmacotherapy has to do with side-effects (Jamison, Gerner, & Goodwin, 1979). Here, the therapist must show a high level of respect, and empathy for the patient’s feelings. Medications such as lithium, carbamazepine, monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, valproate, lamotrigine, and the like can have rather bothersome side-effects, including weight gain, fine motor tremors, acne, and others (Gorman, 1995). The prescriber must be willing to collaborate with the patients in helping them to find the right titrations so that side-effects are reduced, without compromising therapeutic effect. While it may be evident to patients that side-effects of medications are less aversive than the symptoms of full-blown BD, it is less apparent to patients that medications are as useful when BD symptoms are in remission (Jamison, 1995). Therapists must remind their BD patients that medications are still necessary, even when they “feel fine”. However, therapists must acknowledge that it is reasonable for the patient to wish to be free of the medications – indeed, to be free of the disorder altogether. Additionally, BD patients maintain beliefs about their disorder, and about pharmacotherapy, that hinder their compliance. Typical problematic beliefs (Newman et al., 2001; Wright & Schrodt, 1988) include: • • • • • • • • Medication will make me lose my creativity, as well as my happiness. Medication is for people who feel sick. If I feel good, I shouldn’t take medication. If people see me take medication, they will know all about my problems, and they will judge and shun me. If my therapist wants me to take medication, it means that he or she doesn’t respect, accept, and trust me the way I am “naturally”. Medication will turn me into a dull, apathetic conformist. Taking medication infringes on my freedom, which I must maintain at all costs. Medications will change my brain in dangerous ways. I could become a “different person”. I could become addicted. I could damage myself for ever. I don’t like being told what I should do. Therefore, if my doctor (and others) tell me I must take my medications, then I must resist in order to maintain my dignity. Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder 91 It is cognitive therapy’s strength in assessing and modifying dysfunctional beliefs such as the above that make it a psychosocial therapy that is especially well suited to BD (Lam et al., 1999; Newman et al., 2001). Cognitive therapists help their BD patients to identify these beliefs, and then to evaluate their validity, their utility, and their consequences. Then, therapists and their BD patients generate alternative beliefs – in support of taking the required medications – that the patients then test in everyday life. No matter what the patient’s qualms about taking their prescribed medication, whether they be based on practical matters, concerns about side-effects, or the types of beliefs above, it is extremely useful to do a thorough study of the pros and cons of taking medication (Wright & Schrodt, 1988). Hopelessness and suicidality As noted, BD is a chronic disorder, requiring life-long observation, longterm pharmacotherapy, and at least periodic psychosocial therapy as well. If BD patients are fortunate, and they receive the care they need, there is hope that they can keep their disorder under sufficient control to experience a high quality of life. Unfortunately, many BD patients are undertreated, and/or underutilise their treatment, which increases the chances of repeated episodes throughout the life cycle. Further, there is some evidence that with each new cycle of mood disturbance, the risk of subsequent episodes increases (Post, 1992). This has been called the “kindling effect” (Bauer & McBride, 1996), and it represents major difficulty in the lives and treatments of BD patients who have had a significant history of the effects of the disorder. Therapists recognise such BD patients as those who enter treatment with a record of numerous, previous therapists, and multiple past hospitalisations. This state of affairs is discouraging enough for therapists, who must work very hard and pay extra close attention in order to provide these BD patients with the very high standard of necessary care. However, it is far more discouraging for the BD patients themselves, many of whom have seen lives of promise be cruelly interrupted, and high hopes crushed. In such cases, the depressive phases of the disorder often are quite severe, and the risk for suicide is chronically elevated. Indeed, BD is one of the most lethal psychiatric disorders (Nilsson, 1995; Simpson & Jamison, 1995). Therefore, therapists who treat BD patients must always be aware of their degree of hopelessness, as this variable has been found to be an important predictor of future suicide (Beck, Steer, Beck, & Newman, 1993; Beck, Steer, Kovacs, & Garrison, 1985; Young, Fogg, Scheftner, Fawcett, Akiskal, & Maser, 1996). This suggests that therapists must help their BD patients to generate positive, achievable goals for the future. At the same time, they must be very empathic regarding their BD patients’ grief over what has been lost, as well as their fears about setbacks in the future. A verbal contract in which 92 Cory F. Newman the patients pledge to do all that is possible to help themselves, and to solicit help from others (including professionals) before any suicidal action is taken, should be a routine part of therapy (Ellis & Newman, 1996). For some patients, their wariness about the future is a disincentive to collaborate in the therapeutic process. They believe that “I am not going to get better anyway, so there is no point in torturing myself with all these medications, all these appointments, and all these restrictions on my behaviour.” The therapist’s task – and a challenging one at that – is to help the patients reframe this belief so that they understand that a long-range plan of treatment and self-help skills offers the best chance for normal, fulfilling life. It goes without saying that if therapists are to convince their BD patients that it is worth the effort to try to overcome their disorder, the therapists themselves must demonstrate the same conviction in their own efforts. A high level of involvement on the parts of both the patient and therapist is one of the best safeguards against hopelessness and suicidality. Empirical tests of the treatment model Perhaps the groundbreaking study was Cochran’s (1984) randomised controlled trial comparing cognitive therapy with treatment-as-usual for bipolar patients. Her data provided evidence that cognitive therapy could be used to help these patients adhere more successfully to their medication regimens, and therefore to maintain better functioning. More recently, there have been a number of studies confirming the efficacy of cognitive therapy in enhancing the overall treatment package for bipolar patients. In a group therapy format, Palmer et al. (1995) and Hirshfeld et al. (1998) independently found support for the efficacy of cognitive therapy with bipolar patients. In terms of individual treatment, the outcome data of Perry, Tarrier, Morriss, McCarthy, and Limb (1999), Lam et al. (2000), and Scott, Garland, and Moorhead (in press) provide further evidence of the promise of cognitive therapy in helping bipolar patients attain longer periods of euthymia and fewer episodes of symptoms and hospitalisation. Currently, a cognitive behavioural approach to the treatment of bipolar patients is being tested in the context of a 20-site study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD; Principal Investigators, Gary S. Sachs, MD, and Michael E. Thase, MD) is a longitudinal study that will evaluate outcomes associated with combined psychosocial-pharmacological interventions. The manualised cognitive therapy being used in the STEP-BD project (Otto, Reilly-Harrington, Kogan, Henin, & Knauz, 1999) will be used to improve bipolar patients’ quality of life across a wide range of variables, above and beyond simple measures of mood per se. Given the 5–8 year scope of the data collection, it will be interesting to assess the staying power of the therapeutic effects of cognitive therapy. Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder 93 References Alloy, L.B., Reilly-Harrington, N.A., Fresco, D.M., Whitehouse, W.G., & Zechmeister, J.S. (1999). Cognitive styles and life events in subsyndromal unipolar and bipolar disorders: Stability and prospective prediction of depressive and hypomanic mood swings. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 13, 21–40. Basco, M.R. & Rush, A.J. (1996). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Bipolar Disorder: New York: Guilford. Bauer, M.S., Crits-Christoph, P., Ball. W.A., DeWees, E., McAllister, T., Alahi, P., Cacciola, J., & Whybrow, P.C. (1991). Independent assessment of manic and depressive symptoms by self-rating: Scale characteristics and implications for the study of mania. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 807–812. Bauer, M. & McBride, L. (1996). Structured Group Psychotherapy for Bipolar Disorder: The Life Goals Program. New York: Springer. Beck, A.T., Rush, A.J., Shaw, B., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford. Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., Beck, J.S., & Newman, C.F. (1993). Hopelessness, depression, suicidal ideation, and clinical diagnosis of depression. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 23, 139–145. Beck, A.T., Steer, R., Kovacs, M., & Garrison, B. (1985). Hopelessness and eventual suicide: A ten-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 559–563. Beck, A.T., Wright, F.D., Newman, C.F., & Liese, B.S. (1993). Cognitive Therapy of Substance Abuse. New York: Guilford. Beck, J.S. (1995). Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York: Guilford. Burns, D. (1980). Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. New York: William Morrow. Calabrese, J.R., Bowden, C.L., McElroy, S.L., Cookson, J., Andersen, J., Keck, P.E., Rhodes, L., Bolden-Watson, C., Zhou, J., & Ascher, J.A. (1999). Spectrum of activity of lamotrigine in treatment refractory bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 1019–1023. Chor, P., Mercier, M., & Halper, I. (1988). Use of cognitive therapy for treatment of a patient suffering from bipolar affective disorder. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 2, 51–58. Clark, D.M., Salkovskis, P.M., & Chalkley, A.J. (1985). Respiratory control as a treatment for panic attacks. Journal of Behaviour Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 16, 23–30. Cochran, S. (1984). Preventing medical non-compliance in the outpatient treatment of bipolar affective disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52, 873–878. Fieve, R. (1975). Moodswing. Toronto: Bantam Books. Ehlers, C.L., Kupfer, D.J., Frank, E., & Monk, T.H. (1993). Biological rhythms and depression: The role of zeitgebers and zeitstorers. Depression, 1, 285–293. Ellis, T.E. & Newman, C.F. (1996). Choosing to Live: How to Defeat Suicide through Cognitive Therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger. Goldberg, J.F. & Harrow, M. (1999). Poor-outcome bipolar disorders. In J.F. Goldberg & M. Harrow (Eds.), Bipolar Disorders: Clinical Course and Outcome (pp. 1–19). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. 94 Cory F. Newman Goldfried, M.R. & Davison, G.C. (1976). Clinical Behavior Therapy. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston. Goodwin, F. & Jamison, K. (1990). Manic-Depressive Illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gorman, J.M. (1995). The Essential Guide to Psychiatric Drugs (2nd ed.). New York: St. Martin’s Press. Greenberger, D. & Padesky, C.A. (1995). Mind over Mood: A Cognitive Therapy Treatment Manual for Clients. New York: Guilford Press. Hirshfeld, D.R., Gould, R.A., Reilly-Harrington, N.A., Morabito, C., Cosgrove, V., Guille, C., Friedman, S., & Sachs, G.S. (1998, November). Short-term adjunctive cognitive-behavioral group therapy for bipolar disorder: Preliminary results from a controlled trial. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy conference, Washington, DC. Jamison, K.R. (1995). An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness. New York: Knopf. Jamison, K.R. & Akiskal, H. (1983). Medication compliance in patients with bipolar disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 6, 175–192. Jamison, K.R., Gerner, R.H., & Goodwin, F.K. (1979). Patient and physician attitudes toward lithium. Archives of General Psychiatry, 36, 866–869. Johnson, S.L. & Roberts, J. (1995). Life events and bipolar disorder: Implications from biological theories. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 434–439. Kahn, D.A., Ross, R., Printz, D.J., & Sachs, G.S. (2000). Treatment of bipolar disorder: A guide for patients and families. In G.S. Sachs, D.J. Printz, D.A. Kahn, D. Carpenter, & J.P. Docherty (Eds.), Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: The Expert Consensus Guidelines Series (pp. 97–104). New York: McGraw-Hill. Keck, P.E., McElroy, S.L., & Bennett, J.A. (1994). Pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of valproic acid. In R.T. Joffe & J.R. Calabrese (Eds.), Anticonvulsants in Mood Disorders (pp. 27–42). New York: Marcel Dekker. Ketter, T.A. & Post, R.M. (1994). Clinical pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of carbamazepine. In R.T. Joffe & J.R. Calabrese (Eds.), Anticonvulsants in Mood Disorders (pp. 147–188). New York: Marcel Dekker. Lam, D.H., Bright, J., Jones, S., Hayward, P., Schuck, N., Chisholm, D., & Sham, P. (2000). Cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder – A pilot study of relapse prevention. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24, 503–520. Lam, D.H., Jones, S.H., Hayward, P., & Bright, J.A. (1999). Cognitive Therapy for Bipolar Disorder: A Therapist’s Guide to Concepts, Methods, and Practice. Chichester, UK: Wiley. Lam, D.H. & Wong, G. (1997). Prodromes, coping strategies, insight and social functioning in bipolar affective disorders. Psychological Medicine, 27, 1091–1100. Leahy, R.L. (1999). Decision making and mania. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 13, 83–105. Leahy, R.L. & Beck, A.T. (1988). Cognitive therapy of depression and mania. In A. Georgotas & R. Cancro (Eds.), Depression and Mania. New York: Elsevier. Miklowitz, D. & Goldstein, M.J. (1997). Bipolar Disorder: A Family-focused Treatment Approach. New York: Guilford Press. Needleman, L.D. (1999). Cognitive Case Conceptualization: A Guide for Practitioners. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Cognitive therapy of bipolar disorder 95 Newman, C.F. (1994). Understanding client resistance: Methods for enhancing motivation to change. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 2(1), 47–69. Newman, C.F. (in press). Reducing the risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorder: Interventions and safeguards. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. Newman, C.F., Leahy, R.L., Beck, A.T., Reilly-Harrington, N.A., & Gyulai, L. (2001). Bipolar Disorder: A Cognitive Therapy Approach. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Nezu, A.M., Nezu, C.M., & Perri, M.G. (1989). Problem-solving Therapy for Depression: Theory, Research, and Clinical Guidelines. New York: Wiley. Nilsson, A. (1995). Mortality in recurrent mood disorders during periods on and off lithium. Pharmacopsychiatry, 28, 8–13. Otto, M.W., Reilly-Harrington, N.A., Kogan, J.N., Henin, A., & Knauz, R.O. (1999). Cognitive-behavior therapy for bipolar disorder: Treatment manual. Unpublished manuscript, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Overholser, J.C. (1988). Clinical utility of the Socratic method. In C. Stout (Ed.), Annals of Clinical Research (pp. 1–7). Des Plaines, IL: Forest Institute. Palmer, A.G., Williams, H., & Adams, M. (1995). Cognitive-behavioral therapy in a group format for bipolar affective disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23, 153–168. Perry, A., Tarrier, N., Morriss, R., McCarthy, E., & Limb, K. (1999). Randomised controlled trial of efficacy of teaching patients with bipolar disorder to identify early symptoms of relapse and obtain treatment. British Medical Journal, 318, 139–153. Post, R. (1992). Transduction of psychosocial stress into the neurobiology of recurrent affective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 999–1010. Post, R.M., Leverich, G.S., Altshuler, L., & Mikalauskas, K. (1992). Lithiumdiscontinuation-induced refractoriness: Preliminary observations. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 1727–1729. Pretzer, J.L., Beck, A.T., & Newman, C.F. (1989). Stress and stress management: A cognitive view. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 5(4), 305–316. Reilly-Harrington, N.A., Alloy, L.B., Fresco, D.M., & Whitehouse, W.G. (1999). Cognitive styles and life events interact to predict bipolar and unipolar symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 567–578. Sachs, G.S., Printz, D.J., Kahn, D.A., Carpenter, D., & Docherty, J.P. (2000). Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder. The Expert Consensus Guidelines Series. New York: McGraw-Hill. Scott, J. (1996). Cognitive therapy for clients with bipolar disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 3(1), 29–52. Scott, J., Garland, A., & Moorhead, S. (in press). A randomised controlled trial of cognitive therapy for bipolar disorders. Psychological Medicine. Simpson, S.G. & Jamison, K.R. (1999). The risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60 (Suppl. 2), 53–56. Tohen, M. & Zarate, C.A. (1999). Bipolar disorder amd comorbid substance abuse disorder. In J.F. Goldberg & M. Harrow (Eds.), Bipolar Disorders: Clinical Course and Outcome (pp. 171–184). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Winters, K. & Neale, J. (1985). Mania and low self-esteem. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 94, 282–290. 96 Cory F. Newman Wright, J.H. & Schrodt, G.R., Jr. (1988). Combined cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy. In A. Freeman, K.M. Simon, L.E. Beutler, & H. Arkowitz (Eds.), Comprehensive Handbook of Cognitive Therapy. New York: Plenum. Young, M.A., Fogg, L.F., Scheftner, W., Fawcett, J., Akiskal, H., & Maser, J. (1996). Stable trait components of hopelessness: Baseline and sensitivity to depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105, 155–165. Chapter 4 Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder Gregoris Simos The definition of panic disorder (PD) as a separate nosological entity in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition – Revised (DSM-III-R) of the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 1987), triggered a flood of empirical research into this disorder. Klein’s (1964, 1967, 1981) claim that patients with recurrent panic attacks, contrary to patients with more diffuse and generalised forms of anxiety, respond to imipramine but not benzodiazepines – a finding that gave a rather pure biological quality to the conceptualisation of panic disorder – was particularly influential to the establishment of panic disorder as a separate diagnostic entity. A large number of subsequent studies showed that several biochemical and physiological manipulations (infusions of sodium lactate, yohimbine, isoproterenol, oral or intravenous administration of caffeine, voluntary hyperventilation, inhalation of carbon dioxide) frequently induce panic attacks in patients suffering from panic disorder but rarely do so in controls (Appleby, Klein, Sachar, & Levitt, 1981; Liebowitz, Gorman, Fyer et al., 1985; Charney, Heninger, & Breier, 1984; Rainey, Pohl, Williams et al, 1984; Charney, Heninger, & Jatlow, 1985; Uhde, Roy-Byrne, Vittone et al, 1985; Clark, Salkovskis, & Chalkley, 1985; van den Hout & Griez, 1984). Biologically orientated researchers have described these procedures as biological challenge tests and have assumed that pharmacological and physiological manipulations have a direct panic-inducing effect and that individuals who are susceptible to these manipulations have a neurochemical disorder. Until 1987 panic attacks were considered to be secondary to agoraphobia. Under this notion, psychological treatments had focused mainly on the extinction of agoraphobia. Behavioural treatment for agoraphobia had in many instances proved its effectiveness. Repeated in vivo exposure to agoraphobic situations had as a result rapid decrease in agoraphobic fear and avoidance; consequently frequency of panic attacks also decreased (Barlow & Wolfe, 1981; Jansson & Ost, 1982). Comparative evaluation of behaviour therapy for agoraphobia with other psychological treatments showed that treatments that do not incorporate exposure to avoided situations do not 98 Gregoris Simos have much efficacy against agoraphobic fears. Agoraphobic fear and avoidance were minimally affected by hypnosis (Marks, Gelder, & Edwards, 1968), problem-solving therapy (Cullington, Butler, Hibbert, & Gelder, 1984), or assertiveness training (Emmelkamp, van der Hout, & de Vries, 1983). Although exposure therapy was found to be the most effective psychological treatment for agoraphobia, and most follow-up studies conducted on an average of about four years after treatment indicated that most patients retained their gains (Emmelkamp & Kuipers, 1979; McPherson, Brougham, & McLaren, 1980; Munby & Johnston, 1980), only about 60–70% of agoraphobics show clinically significant improvement (Jansson & Ost, 1982). Re-analysis of exposure-based studies of agoraphobia showed an average clinically significant improvement rate of 58% and average recovery rate of 27%; patients at follow-up had mostly retained treatment gains, whereas some patients had further improved (Jacobson, Wilson, & Tupper, 1988). Jacobson et al.’s conclusion that exposure alone did not seem to be a total solution to the problem of agoraphobia resembled in some way a comment made by Gelder and Marks much earlier (1966). Gelder and Marks had already pointed out that apparently unexplained, uncued to external stimuli, and often extremely difficult to treat, panic attacks could inhibit significant progress in behaviour therapy for agoraphobia. This recognition of the significant, yet still limited, effectiveness of behaviour therapy for agoraphobia and panic coincided with the emergence of new psychological theories on the development and maintenance of panic attacks and agoraphobia. Goldstein & Chambless (1978) had already proposed that agoraphobics fear panicking in public places, not public places per se, and suggested a fear-of-fear interoceptive conditioning model of panic disorder with agoraphobia, where symptoms of physiological arousal become the conditioned stimuli for the powerful conditioned response of a panic attack. According to their model, people who have suffered one or more panic attacks become hyperalert to their sensations, interpret feelings of mild to moderate anxiety as signs of oncoming panic attacks, and react with such anxiety that the dreaded episode is almost invariably induced. Aaron Beck had previously suggested (1976) that in anxiety states, individuals systematically overestimate the danger inherent in a given situation. David Clark (1986, 1988) further elaborating this cognitive concept, proposed that panic attacks result from the catastrophic misinterpretation of certain bodily sensations. According to Clark (1986), external or internal stimuli are perceived as a threat, and result in a state of apprehension. A wide range of bodily sensations that normally accompany apprehension are interpreted in a catastrophic fashion, and a further increase in apprehension occurs. Further apprehension produces a further increase in bodily sensations and so on round in a vicious circle which culminates in a panic attack. Contrary to the interoceptive conditioning model these initial bodily sensations may not only be the symptoms of anxiety, but also sensations caused by Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder External stimuli Agoraphobic places Internal stimuli Catastrophic misinterpretation (B) of anxiety symptoms Internal stimuli Non-anxiety body sensations, thoughts, images Catastrophic misinterpretation (A) Fearful predictions Avoidance 99 Anxiety Safety behaviours Hypervigilance Physical and/or Cognitive symptoms Figure 4.1 The cognitive model of panic disorder. different emotional states (excitement, anger), or by some quite innocuous events (suddenly getting up, exercise, drinking coffee, fatigue, illness, premenstrual tension). These sensations are perceived as much more dangerous than they really are, and are also interpreted as indicative of an immediate, impending disaster. The catastrophic appraisal of sensations produces an immediate anxiety response with further and more intense symptoms, and very quickly culminates in a panic attack. The cognitive model of panic disorder is illustrated in Figure 4.1. Based on Clark’s (1986) original “vicious circle” model of panic, it also incorporates more recent theorising and elaboration on the cognitive model of panic disorder (Salkovskis, 1991; Rachman, 1991; Salkovskis, Clark, & Gelder, 1996). According to this model, internal triggering stimuli for a panic attack may be produced by anxiety sensations, or by non-anxiety sensations (or thoughts and images). In the first instance, bodily sensations of elevated anxiety are misinterpreted catastrophically, which in turn produces more symptoms and leads to a panic attack. Sequence of events is thus: anxiety-produced sensations become anxiety-producing through their misinterpretation: anxiety-produced sensations ➔ misinterpretation ➔ anxiety-producing sensations ➔ panic. In the second instance, non-anxiety sensations are interpreted catastrophically, thus leading to elevated anxiety; symptoms of elevated anxiety are further misinterpreted catastrophically, producing more symptoms and leading to a panic 100 Gregoris Simos attack. In this case, sequence of events is thus: non-anxiety-produced sensations become anxiety-producing through their misinterpretation, and anxietyproduced sensations become even more anxiety-producing through a further misinterpretation: non-anxiety-produced sensations ➔ first misinterpretation ➔ anxiety-produced sensations ➔ second misinterpretation ➔ anxiety-producing sensations ➔ panic. In this second case, panic patients become habitually victims of two, at least, consecutive misinterpretations, something that apparently has implications for the development of effective interventions. Panic disorder is maintained by two additional processes: hypervigilance and safety behaviours. As panic disorder patients develop the tendency to misinterpret catastrophically, and consequently develop the fear of, certain bodily sensations, they become hypervigilant and repeatedly scan their body. Although such an increased self-focused attention reflects patients’ attempts to control stimuli (Kendall & Ingram, 1987), and patients become capable of noticing sensations which many other people would not be aware of, these sensations are taken as further evidence of a serious physical or mental disorder, and may consequently trigger another panic attack. Safety behaviours tend to maintain patients’ negative cognitions and are either anticipatory/avoidant or consequent/escape (Salkovskis, 1991). Since a safety seeking behaviour is perceived to be preventive, and focused on especially negative consequences (e.g., death, illness, humiliation), spontaneous disconfirmation of threat is made particularly unlikely by such safety seeking behaviours. Avoidance, either overt in the form of agoraphobia or in more subtle forms, prevents disconfirmation of panic-related cognitions and may thus maintain panic disorder. Within-situation safety seeking behaviours result in the maintenance of catastrophic cognitions in the face of repeated panic, during which the feared catastrophes do not occur (Salkovskis et al., 1996). Overt avoidance, on the other hand, is the most common behavioural consequence of panic; the major determinant of panic-related avoidance behaviour is the person’s present prediction of the probability of experiencing a panic in specified circumstances. While panic episodes in general are followed by an increase in the prediction of future panics, and expected panics are followed by little or no change in predictions of panic, unexpected panics contribute to a significant overprediction of panic (Rachman, 1991). Since agoraphobic avoidance does not necessarily disconfirm predictions of panic, and spontaneous panics are by definition unpredicted, an increase in fearful predictions predisposes to elevated levels of anxiety, and in a selffulfilling prophecy mode, may result in a panic attack. Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 101 Cognitive behavioural treatments of panic Preliminary cognitive behavioural treatment for panic attacks gave a particular emphasis on the importance of hyperventilation in the production of panic attacks and, consequently, emphasis on breathing retraining techniques (Clark, Salkovskis, & Chalkley, 1985; Salkovskis, Jones, & Clark, 1986; Clark, 1988). Since the cognitive behavioural approach involves identifying patients’ negative interpretations of bodily sensations experienced in panic attacks, and suggests alternative non-catastrophic interpretations of such sensations, the approach by Clark at al. (1985) and Salkovskis et al. (1986) focused on the view that the bodily sensations which patients experience in a panic attack are the results of stress-induced hyperventilation rather than the more catastrophic occurrences which they usually fear, e.g. heart attack, stroke, fainting, losing control. Hyperventilation was chosen as an alternative explanation, because the bodily sensations which occur in a panic attack are very similar to those produced by voluntary hyperventilation, and there was evidence that hyperventilation has an important role in the production of some patients’ panic attacks. This treatment approach has several successive steps. In the first step, the cognitions and bodily sensations that are associated with panic are elicited. In the next step the therapist tries to demonstrate that hyperventilation could have produced the symptoms of panic by asking the patient to overbreathe for two minutes. Patients are asked to breathe through their nose and mouth quickly, fully emptying their lungs as they breathe out, and filling them completely as they breathe in. Patients are not told exactly what sensations they are likely to experience, and are not told that the effects of overbreathing might be similar to their panic attacks. The procedure is presented to the patient as a diagnostic exercise. If the patient recognises the bodily sensations induced by hyperventilation as similar to those experienced during a panic attack, this observation becomes the basis for a discussion on the “catastrophic” nature of panic attack symptoms. Therapists can thus help patients to reappraise their symptoms and reattribute them away from catastrophic interpretations, and toward the notion that the patient is suffering from stress-induced hyperventilation. The next step in the treatment involves training of controlled respiration which is incompatible with hyperventilation. Slow (8–12 breaths per minute), shallow, diaphragmatic breathing is intended to be used as a coping technique when a patient thinks a panic is about to start or notices that he has started overbreathing. In the last step, the patient is taught to identify and modify panic triggers. Clark et al. (1985) and Salkovskis et al. (1986) reported impressive evidence for the efficacy of breathing retraining combined with cognitive reattribution in a study of 18, and 9 panic patients, respectively. Substantial reductions in panic attack frequency were observed during the first weeks of treatment. Initial gains, which occurred in the absence of exposure to feared external 102 Gregoris Simos situations, were improved with further treatment, including exposure in vivo if appropriate, and were maintained at 2-year follow-up. A limitation of these studies was that not all panic patients perceive a marked similarity between the effects of voluntary overbreathing and naturally occurring panic attacks. Indeed, in the second study there was evidence that outcome was positively correlated with the extent to which patients perceived this similarity. Nevertheless, it was becoming clear that focus on panic attacks seemed to be more promising than the conventional treatment methods centred on secondary symptoms such as anticipatory anxiety or agoraphobia. Under this principle a series of cognitive behaviour treatment studies were conducted. Various therapeutic processes, mainly cognitive, that arose from the above theories and findings, were used as adjunctive techniques to exposure therapy: self-instructional training (Meichenbaum, 1977), rational-emotive therapy (Ellis, 1962), Beck’s cognitive therapy (Beck, Emery, & Greenberg, 1985) and paradoxical intention (Ascher, 1981), as well as relaxation training and breathing retraining (Emmelkamp, Kuipers, & Eggeraat, 1978; Emmelkamp & Mersch, 1982; Emmelkamp, Brilman, Kuiper, & Mersch, 1986; Williams & Rappoport, 1983; Mavissakalian, Michelson, Greenwald, Kornblith, & Greenwald, 1983; Marchione, Michelson, Greenwald, & Dancu, 1987; Michelson, Mavissakalian, & Marchione, 1988). Findings of the above investigations were interpreted in two different ways. Marks (1987) contended that these investigations suggest that relaxation and cognitive procedures add little to exposure in vivo. However, Hoffart (1993) critically evaluating most of these studies, pointed out that some studies had not attained a methodological level that made it possible to draw any conclusions, or that in nearly all studies (with the exception of the Marchione et al. study, 1987, which actually supported the potentiating effect of Beck’s cognitive therapy), the forms of cognitive therapy that were applied had either not been derived from “true” cognitive models, or had been connected to an explicit cognitive theory. Full or “true” cognitive therapy of panic has been investigated in one naturalistic and four controlled studies. Sokol, Beck, Greenberg, Wright, & Berchick (1989) conducted a naturalistic study with no predetermined duration of treatment in order to examine the effectiveness of cognitive therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. Seventeen panic disorder patients received a mean of 18 individual cognitive therapy sessions. Mean number of panic attacks was reduced significantly to zero at the end of treatment, and there was also a concomitant reduction in self-report measures of depression and anxiety. Furthermore, there was a significant reduction on a measure of cognitive dysfunction during panic attacks, and treatment results were maintained at 12-month follow-up. In the Beck, Sokol, Clark, Berchick, & Wright (1992) study, researchers sought to determine the short- and long-term effects of focused cognitive therapy for panic disorder. Thirty-three psychiatric outpatients with the Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 103 DSM-III (APA, 1980) diagnosis of panic disorder were randomly assigned to either 12 weeks of individual, focused cognitive therapy or 8 weeks of brief supportive psychotherapy based on principles of client-centred therapy. The patients who received supportive psychotherapy were subsequently given the opportunity to cross over to cognitive therapy for 12 weeks. Patients were rated for panic and depression before therapy, after 4 and 8 weeks of therapy, and at 6-month and 1-year follow-up. Clinician ratings and self-ratings of panic frequency and intensity indicated that the focused cognitive therapy group achieved significantly greater reductions in panic symptoms and general anxiety after 8 weeks of treatment, than did the group that received brief supportive psychotherapy. At 8 weeks, 71% of the cognitive therapy group were panic free, compared to 25% of the psychotherapy group. Moreover, 94% of the psychotherapy patients elected to cross over to 12 weeks of cognitive therapy. At 1-year follow-up, 87% of the group that received cognitive therapy only, and 79% of the group that crossed over into cognitive therapy, remained free of panic attacks. In the study by Clark, Salkovskis, Hackmann, Middleton, Anastasiades, & Gelder (1994), 64 panic disorder patients were initially assigned to cognitive therapy, applied relaxation, imipramine (mean 233 mg/day), or a 3-month wait followed by allocation to treatment. During treatment, patients had up to 12 sessions in the first 3 months and up to three booster sessions in the next 3 months. Imipramine was gradually withdrawn after 6 months. Each treatment included self-exposure homework assignments. Cognitive therapy and applied relaxation sessions lasted one hour, while imipramine sessions lasted 25 minutes. Assessments were made before treatment/wait and at 3, 6, and 15 months. Comparisons with the waiting-list showed all three treatments were effective. Comparisons between treatments showed that at 3 months, cognitive therapy was superior to both applied relaxation and imipramine on most measures. At 6 months cognitive therapy did not differ from imipramine and both were superior to applied relaxation on several measures. Since between 6 and 15 months a number of imipramine patients relapsed, at 15 months cognitive therapy was again superior to both applied relaxation and imipramine but on fewer measures than at 3 months. Cognitive measures taken at the end of treatment were significant predictors of outcome at follow-up. The Ost & Westling study (1995) investigated the efficacy of a coping technique, applied relaxation (AR) and cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), in the treatment of panic disorder. Thirty-eight outpatients fulfilling the DSM-IIIR criteria for panic disorder with no (n = 30) or mild (n = 8) avoidance were assessed before and after treatment, and at 1-year follow-up. The patients were treated individually for 12 weekly sessions. The results showed that both treatments yielded very large improvements, which were maintained or further increased at follow-up. There was no difference between AR and CBT on any measure. The proportions of panic-free patients were 65 and 74% at 104 Gregoris Simos post-treatment, and 82 and 89% at follow-up, for AR and CBT, respectively. There were no relapses at follow-up; on the contrary, 55% of the patients who still had panic attacks at post-treatment were panic-free at follow-up. Besides affecting panic attacks, the treatments also yielded marked and lasting changes on generalised anxiety, depression and cognitive misinterpretations. Ost & Westling (1995) concluded that both AR and CBT are effective treatments for panic disorder without avoidance. In the Arnz & van den Hout (1996) study, cognitive therapy was compared with applied relaxation, in a group of panic disorder without agoraphobia patients. Assessments were at pre-, post-treatment, and 1-month and 6-month follow-ups. Significantly more cognitive therapy patients than applied relaxation patients were panic free at the end of treatment, and at both follow-ups. The above studies indicate that properly conducted cognitive therapy is a highly effective treatment for panic disorder, with intention-to-treat analyses indicating 74–94% of patients becoming panic free, and these gains being maintained at follow-ups; effects of the treatment do not seem to be entirely due to non-specific therapy factors (Clark, 1997). What is the position of exposure therapy in the contemporary cognitive behavioural treatment for panic, with or without agoraphobia? Cognitive therapy has anti-panic effects and exposure has anti-agoraphobic effects, while it is suggested that agoraphobia is a secondary complication of panic disorder. It was therefore hypothesised that cognitive therapy reduces not only panic but also agoraphobia, and that it potentiates the effects of exposure in vivo. This hypothesis was tested in the van den Hout et al. study (van den Hout, Arntz, & Hoekstra, 1994). One group of 12 severe agoraphobics were treated with four sessions of cognitive therapy followed by eight sessions of cognitive therapy combined with in vivo exposure. Another group of 12 patients received four sessions of “associative therapy”, a presumably inert treatment that controls for therapist attention, followed by eight sessions of in vivo exposure that was framed in common behavioural terms. The initial cognitive therapy produced a significant reduction in panic frequency, while associative therapy did not affect panic. Neither cognitive therapy alone nor associative therapy alone significantly reduced self-rated agoraphobia or behavioural avoidance. After adding exposure, however, these parameters were clearly and significantly reduced. Cognitive therapy did not seem to potentiate exposure effects. There is a consensus that panic disorder without agoraphobia should be treated with cognitive therapy (with or without breathing retraining, with or without relaxation training), and agoraphobia without a history of panic disorder should be treated with exposure in vivo. But what happens with panic disorder with agoraphobia, the most common form of panic disorder in clinical practice? What actually happens is rather disappointing. Findings from a multicentre anxiety-disorders study investigating, among other variables, the treatment provided, showed that most panic patients received Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 105 medication, usually benzodiazepines, while psychodynamic psychotherapy was the most frequent psychosocial treatment; cognitive and behavioural approaches were less commonly received (Goisman, Warshaw, Peterson et al., 1994). It seems that panic disorder with agoraphobia can be best perceived as a complex syndrome with cognitive, behavioural, and physiological disturbances, and treated accordingly with cognitive restructuring and exposure to both external and interoceptive stimuli. The above integrative form of cognitive behavioural treatment (cognitive restructuring plus interoceptive exposure) of panic disorder without agoraphobia, or its variation (cognitive restructuring plus interoceptive exposure plus exposure in vivo) for panic disorder with agoraphobia was developed and repeatedly evaluated by Barlow and his colleagues (Barlow, Craske, Cerny, & Klosko, 1989; Barlow, 1990; Craske, Brown, & Barlow, 1991). This treatment package includes breathing retraining to correct hyperventilatory breathing patterns, cognitive restructuring to correct catastrophic misinterpretations of benign somatic sensations, and exposure to somatic cues (also called interoceptive exposure) through the use of any of a number of provocation procedures, e.g. hyperventilation, carbon dioxide inhalation, running in place, spinning in a chair (Moras, Craske, & Barlow, 1990). Barlow et al. (1989) reported the results of a long-term clinical outcome study, testing variations of behavioural treatments for panic disorder without agoraphobic avoidance. Treatment consisted of either progressive muscle relaxation, interoceptive exposure therapy plus cognitive restructuring, or a combination of relaxation and interoceptive exposure therapy plus cognitive restructuring. All three treatments were superior on a variety of measures to a waiting-list control group. In the two treatment conditions containing exposure to somatic cues and cognitive therapy, 85% or more of clients were panic free at post-treatment. These were the only groups significantly better than the waiting-list control group on this measure. Relaxation, on the other hand, tended to effect greater reductions in generalised anxiety associated with panic attacks, but was associated with high drop-out rates. The same group of patients was assessed 6 months and 24 months following treatment completion (Craske et al., 1991). Patients in the interoceptive exposure plus cognitive therapy condition tended to either maintain or improve upon their post-treatment status over the 2-year follow-up interval. Fully 81% of the patients in the latter condition remained panic-free at the 24-month assessment. Finally, in a comprehensive review of newly developed psychological approaches for panic, Margraaf, Barlow, Clark, and Telch (1993) conclude that approximately 80% or more of the patients receiving combined cognitive behavioural treatments achieved panic-free status as well as strong and clinically significant improvement in general anxiety, panic-related cognitions, 106 Gregoris Simos depression, and phobic avoidance, while these gains were maintained at follow-ups of up to 2 years. Furthermore, the above authors conclude that success of these psychological treatments compared favourably with the outcome for the established pharmacological treatments. Key points in the treatment of panic disorder Although panic disorder patients are exposed to their dreaded panic attacks and their potentially “catastrophic” consequences countless times, cognitive change is rather unlikely to happen in the absence of treatment. According to the cognitive model this means that their catastrophic predictions are not disconfirmed. This phenomenon is partly explained by the fact that panic disorder is characterised by interpretive, attentional, memory, and interoceptive biases for processing threat (McNally, 1994). Paul Salkovskis, on the other hand, has suggested that, according to a more explicit cognitive hypothesis, safety seeking behaviours may constitute a crucial factor in the maintenance of panic disorder (Salkovskis, 1991; Salkovskis, Clark, & Gelder, 1996). Although avoidant or escape behaviours were well recognised and managed by exposure therapy, panic disorder patients also engage in more subtle or covert avoidant and escape behaviours, e.g. the patient that interprets his dizziness as a sign of imminent collapse may lean on the wall, or the patient that perceives his accelerated heart rate as a sign of an upcoming heart attack may slow down his breath or lean back in his armchair and try to relax. These subtle safety/avoidant behaviours do not allow for disconfirmation of catastrophic predictions and are thus further selfenhanced. Basic principles in the cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder CBT attempts to treat PD by teaching patients to identify, test, and modify the thoughts and beliefs that accompany their panic attacks or their anticipatory anxiety, as well as the avoidance behaviours that may be perpetuating their faulty appraisals and responses. CBT is a collaborative process of investigation, reality testing, and problem-solving between patient and therapist. The therapist does not forcefully exhort patients to change their views and their thinking styles, but instead, tries to accurately understand how patients come to develop their problems, and proceeds to teach patients a set of durable skills that will help them think more objectively and flexibly. We, as therapists, ought to not forget that the evidential basis for the misinterpretations of bodily sensations made in a panic attack may be inaccurate, but the degree of anxiety is rational and proportional to a given patient’s immediate personal and idiosyncratic appraisal of threat (Salkovskis, 1991). Patients are taught to view their thoughts and beliefs as testable hypotheses, and Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 107 encouraged to take graded risks in confronting feared situations in order both to disconfirm their predictions, and to learn to cope actively with stresses. The therapist does not attempt merely to change the content of a patient’s thinking, but assists the patient in adopting an improved thinking process (Newman & Haaga, 1992). CBT for PD, as is the case for CBT for any other mental disorder, is a structured and highly active form of treatment with therapy sessions in which agendas are set, goals are defined, priorities are established, and problems are concretised (Newman, 1992). The therapist and the patient share the responsibility for the work of therapy, with the therapist being willing to respond to direct questions with direct answers, but also using Socratic questioning in order to help the patient to gradually learn to recognise and solve problems for himself. Further, the implementation of between session homework assignments helps patients to translate their new hypotheses and goals into actual behaviours that increase self-esteem, reduce anxiety, fears and avoidance, and improve the patient’s quality of life. Cognitive behaviour treatment techniques Although CBT for PD is a highly structured treatment process, and there are excellent descriptions of the basic elements of this process and on how a therapist will deal with almost all panic disorder aspects, CBT for PD is rarely described in a step-by-step or session-by-session manner (Clark & Salkovskis, 1987a; Beck, 1988; Clark, 1989, 1996, 1997). From all the above published work, Clark’s 1996 description of specialised treatment procedures is the briefest and most conclusive, while Clark’s 1989 is the most extensive. Clark’s (1996) delineation of the Oxford Cognitive Therapy Package for Panic Disorder is as follows: The Cognitive Therapy Package uses a wide range of cognitive and behavioural procedures to help patients change their misinterpretations of bodily sensations and to modify the processes that tend to maintain the misinterpretations. The cognitive techniques include using review of a recent panic attack to derive the vicious circle model, identifying and challenging patients’ evidence for their misinterpretations, substituting more realistic interpretations and restructuring images. The behavioural procedures include inducing feared sensations (by hyperventilation, by reading pairs of words representing feared sensations and catastrophes, or by focusing attention on the body) in order to demonstrate the true cause of the panic symptoms, and dropping safety behaviours (such as holding onto solid objects when feeling dizzy) and entering feared situations in order to allow patients to disconfirm their negative predictions about the consequences of their symptoms. (Clark, 1996, p. 328) 108 Gregoris Simos Beck (1988, p. 106) describes nine steps in the treatment of panic disorder: (1) Explanation of the nonpathological nature of symptoms; (2) reappraisal of the panicogenic sensations and of the idiosyncratic meaning and interpretations; (3) eliciting automatic thoughts and images associated with attack; (4) enhancement and re-evaluation of symptoms and responding to automatic thoughts; (5) relaxation, breathing exercises; (6) induction of miniattacks in office by hyperventilation, exercise, imagery, etc.; (7) distraction; (8) systematic exposure; and (9) use of flash cards. Although it is useful to remember all these steps, the above steps are not always taken in this specific order in clinical practice. Along the Oxford tradition, Adrian Wells (1997, pp. 131–132), after giving his account of the cognitive techniques for the treatment of panic disorder, presents a useful example treatment outline. This example includes gross session-by-session guidelines: Session 1: (a) Map out panic circle for a recent attack, (b) socialise using circle and socialisation procedures, (c) identify range of misinterpretations/beliefs/safety behaviours, and (d) homework – fill out panic diary with misinterpretations, listen to therapy session tape. Session 2: (a) Map out circle for recent panic recorded in diary, (b) focus on key beliefs and use behavioural and verbal reattribution, (c) introduce concept of safety behaviours, and (d) homework – cognitive diary, experiment by dropping safety behaviours, listen to therapy session tape. Sessions 3–7: (a) Continue to map out circles for panics, including safety behaviours, focus on key beliefs, (b) in-session induction experiments to challenge different beliefs, (c) verbal reattribution and generation of rational responses based on this and on behavioural experiments, and (d) homework – specific exposure experiments/dropping safety behaviours/pushing symptoms. Continue panic diary, include rational responses, listen to therapy session tape, write a summary. Sessions 8–12: (a) Challenge remaining beliefs, (b) identify/eliminate remaining safety behaviours/avoidance, (c) relapse prevention, and (d) homework – continue pushing symptoms, go in search of a panic to test fears, work on blueprint. As Wells (1997, p. 280) notes, therapists should use sessional responses on the Panic Rating Scale to guide the focus of treatment sessions. (The Panic Rating Scale serves a similar function to the panic diaries described in the following page.) It sounds logical that on treating a panic disorder patient, a therapist has to adhere to the therapy rationale, but must also keep a certain degree of flexibility in order to tailor treatment procedures to the individual patient. Development of a patient-specific case formulation seems to emerge as an integral part of contemporary CBT for panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia (Taylor, 2000). Such a case formulation requires the clinician to formulate and test hypotheses about the predisposing, precipitating, and protective factors in the patient’s problems, and to select interventions according to these hypotheses. Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 109 Beck and his colleagues devised a treatment protocol for panic disorder called Focused Cognitive Therapy (FCT) for Panic Disorder (Beck, 1992a). A version of this 12-session treatment protocol was the one that was used in the controlled study mentioned earlier (Beck et al., 1992). This treatment proved highly effective, as 71% of the cognitive therapy group were panic free at week 8, and 87% of this group remained free of panic attacks at 1-year follow-up. An adapted version for the needs of this book will be presented here. The aim of FCT for PD is to reduce belief in patients’ catastrophic misinterpretations, and for this purpose it uses a variety of procedures and techniques: education, drawing panic scenarios, panic inductions, behavioural experiments, listing evidence against and disputing evidence supporting misinterpretations, identification and reduction of subtle avoidant behaviours, daily work on agoraphobic avoidance. FCT also teaches a limited number of coping skills to panic patients (e.g. controlled breathing, refocusing, relaxation); coping skills are taught in order to control anxiety, although the therapist emphasises that these skills are not necessary, or an integral part of therapy, since panic attacks are not dangerous. Session 1 1 2 3 Introduction of panic diary. Education about panic: handout, cognitive model of anxiety, panic scenario. Summary and discussion of therapy plan. A panic diary is useful for data collection and planning interventions. A panic diary may have either the form suggested by Clark (1989) or the one suggested by Beck (1992b). This first form has several columns: day, description of situations where panic attack occurred, a column for each of the DSM-IV (APA, 1994) physical and cognitive symptoms, severity of panic (0–100), and number of panic attacks per day. The latter form (Weekly Panic Log) has six columns: (a) date, time, and the duration of panic attack; (b) situation in which panic occurred, severity of panic attack (1–10); (c) symptoms and sensations during a panic attack (in the bottom of Weekly Panic Log there is a list of DSM physical and cognitive symptoms, and the patient writes down in the column symptom numbers); (d) interpretation of sensations and accompanying thoughts and images; (e) full-blown/limited symptom panic attack; patient tries to explain why it was a limited symptom attack and not a full-blown attack, and vice versa; (f) patient’s response to panic attack, including any medication taken. 110 Gregoris Simos A most complicated form of panic diary is the one where the patient, in addition to the information provided above, tries to identify the sequence of symptoms–thoughts in a panic attack. This kind of information is difficult for the patient to provide at the beginning of treatment, at least, but this information will help the therapist draw the vicious circle of a panic attack and introduce the cognitive theory of panic. From such a detailed diary, therapists are often able to reach a variety of conclusions and suggest appropriate, and sometimes simple, interventions. For example, review of a teacher’s diary showed that this patient was experiencing heightened anxiety, and sometimes a panic attack at approximately 11 a.m. Detailed discussion of this finding revealed that “anxiety” related to his eating habits; as he used to have his dinner early in the evening, and he almost invariably did not have breakfast, 11 a.m. seemed to be the time of the day with his lowest blood sugar levels. Introduction of a proper breakfast, as an experiment to test the low blood sugar hypothesis, reversed this condition. Review of a housewife’s diary showed that she was having some of her most severe panics at midday; appropriate investigation showed that during the morning, and after her children had gone to school, she had the habit of visiting neighbours or inviting them “to have coffee”. It was apparent that by midday she had already had several cups of coffee, and that misinterpretation of the autonomic arousal produced by caffeine was the trigger of her panic attacks. Reduction in the number of coffees consumed in a day resulted in a significant decrease in her panic attack frequency. Education about panic seems to be a powerful tool in the management of panic. Several centres provide the panic patient with written material on the physiology of anxiety and panic (Clark & Salkovskis, 1987b; Barlow & Cerny, 1988; Craske & Barlow, 1993; Greenberg & Beck, 1987; Simos, 1991) and/or suggest to the patient to read specific texts. For example, appropriate books for this purpose are Living with Fear by Isaac Marks (1978) or Panic Disorder: The Facts by Stanley Rachman and Padmal de Silva (1996). Written material of this kind provides information about the fight-or-flight response, the adaptive nature of such a response, the usefulness of non-pathological anxiety, and the self-regulation of anxiety and panic reactions. Information about the nondangerous nature of panic and the non-catastrophic consequences of anxiety symptoms help patients understand that the catastrophic misinterpretation of their panic symptoms has no scientific basis. The recognition, for example, that people faint when there is a drop both in their heart rate and in their arterial pressure, and that during a panic attack there is usually a small increase in their arterial pressure, makes panic patients see that experiencing accelerated heart rate during an attack is incompatible with collapsing, and their consequent fear of collapsing. Moreover, patient handouts include information about the cognitive model in general (thoughts influence emotions, behaviour, and physiological responses), and the cognitive model of panic in particular (catastrophic misinterpretation of bodily sensations of various origins). Education Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 111 is an integral part of CBT for panic, and it is given throughout the whole therapy. Sometimes it is useful even to refer to some impressive experimental findings, depending always on the stage of treatment, and the quality of therapeutic relationship. The Ehlers, Margraaf, Roth, Taylor, and Birbaumer (1988) false heart rate feedback experiment is especially effective. After briefly presenting the experimental procedure to the patient, the therapist asks the patient to guess what the results of the experiment were. Interestingly, the patient’s predictions are almost invariably towards the right direction, showing that the patient has already understood the way that misinterpretation of bodily symptoms leads to the development of a panic attack. Eliciting idiosyncratic data for the construction of the cognitive vicious circle model or a panic scenario is of primary importance. For this purpose, therapist and patient scrutinise a specific, probably more recent, and typical for a given patient panic attack, and through persistent Socratic questioning they elicit all appropriate information pertaining to sequence of bodily sensations, catastrophic thoughts, and emotional, physiological, and behavioural reactions. Safety behaviours or subtle avoidance are also important for the therapist and patient to identify. Safety behaviours not only prevent disconfirmation of the patient’s belief in catastrophic misinterpretation, but may also directly exacerbate physical and cognitive symptoms. A patient, for example, who walks around her neighbourhood, perceives that her heart is beating faster than usual, chooses to go straight back home, and starts walking quickly. The more quickly she walks, the more her heart accelerates – an apparently normal reaction to increased needs in blood and oxygen supply – and the more convinced she becomes that she is having a panic attack, her heart “will break”, and she will collapse. Her heart rate returns to normal only after she is home, sits in an armchair, or lies in her bed, and such a safety-behaviour makes her believe that what she did (walk quickly, return home, lie in bed) was the “right thing”. In addition to the details given in session by the patient, useful information about a panic scenario can also be obtained by appropriate questionnaires. The Body Sensations Questionnaire and Agoraphobic Cognitions Questionnaire (Chambless, Caputo, Bright, & Gallagher, 1984) access most feared bodily sensations and most prevalent catastrophic thoughts, respectively, and there is evidence of significant and meaningful relationships between certain symptoms and specific cognitions (Warren, Zgouridis, & Englert, 1990; Simos, Dimitriou, Vaiopoulos, & Paraschos, 1994). The Panic Belief Questionnaire (Greenberg, 1989; Brown, Beck, Greenberg, Newman, Beck, Tran, Clark, Reilly, & Betz, 1991) assesses beliefs and assumptions related to panic and oneself, and gives the therapist a clear understanding of a panic patient’s thoughts and behaviours, as well as ideas for appropriate cognitive and behavioural interventions. The Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck & Steer, 1991) is another useful source of information on subjective, neurophysiological, and panic symptoms related to a patient’s recent anxiety experiences. 112 Gregoris Simos Reading therapy session notes and relevant texts on anxiety and panic is part of the homework given to the patient at the end of the first session. As continuous monitoring of panic attacks and appropriate use of the panic diary are essential ingredients in this part of therapy, patients are especially instructed for this purpose. Session 2 1 2 3 4 Review panic diary and degree of belief in catastrophic misinterpretation. Review homework. Panic induction. Review panic scenario with places/techniques for intervention. Therapist and patient review panic diary and degree of belief in catastrophic misinterpretations. Specific panic attacks become the focus of discussion in order for the patient and therapist to identify precipitating events, sequence of sensations, thoughts, and behaviours, and especially overt and subtle avoidant/escape behaviours. The therapist also asks for feedback on topics discussed in the first session, and especially credibility of the cognitive model. Such a feedback has already been elicited in the first session; however, after the patient has experienced his real-life difficulties and some additional panic attacks, he may have already seen how the cognitive model works, or does not work, in practice, and thus feedback may be more extensive in this case. Questions arising from the written material that was given or suggested in the first session are appropriately answered. Panic induction techniques have many aims. They are designed to test predictions based on a patient’s beliefs, help patients reattribute their symptoms to more benign, and less catastrophic, processes, and also reveal subtle avoidant/escape behaviours. Panic induction is normally presented as a diagnostic experiment and without a clear rationale, since a detailed rationale can interfere with the impact of the procedure. Panic inductions are implemented in such a way as to induce symptoms which closely resemble those normally present and misinterpreted during a panic attack. Panic induction through hyperventilation or overbreathing is most commonly used because overbreathing usually produces a wide range of panicogenic sensations, such as palpitations, dizziness, faintness, blurred vision, feeling of unsteadiness, trembling, feelings of unreality, or chest discomfort. Panic induction through hyperventilation is considered a safe procedure, but it should not be practised with patients suffering from a narrow range of medical conditions, like cardiopulmonary problems and epilepsy, or with patients who are pregnant. Given the young age of most panic patients, these problems are usually rare. Panic induction through hyperventilation has already been described earlier in this chapter, but some points need to be made. The patient fills out a Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 113 Sensation Checklist or patient and therapist review a recent or typical panic attack and write down the most common and intense symptoms during such an attack, before panic induction. Review of a recently completed Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) can also serve the same purpose. The therapist informs the patient that he may stop the procedure earlier if he wishes to, but also points out that it is essential for the patient to try as much as he can. The patient is asked to overbreathe for two minutes, while the therapist models an appropriate way of deep and rapid breathing. The therapist encourages the patient to continue, while giving a continuous feedback to the patient on the time left until the end of the overbreathing period. After the patient stops overbreathing, the patient is asked to rate on a 0–100% basis similarities between the overbreathing – or any other panic induction technique – and an actual panic attack. The therapist uses a variety of questions to elicit appropriate information and help the patient arrive at the right conclusions. Questions like “What emotions did you feel during this experience?”, “What were you worried might happen?”, “What pictures or images went through your mind?”, “What sensations made you believe that the worst could happen?”, “Did you try to make the experience easier or safer?” “Were you telling yourself anything in order to feel better?”, “What do you conclude?”, “What do you make of the fact that there is a similarity between overbreathing and panic attack?”, “What is your breathing like before or during a panic attack?” Forced hyperventilation sometimes has powerful effects. There are patients who stop overbreathing after only a couple of breathing cycles, or suddenly grip on their chair, or even steadily lean their arm on a nearby wall, in order to prevent a full-blown panic attack, or the catastrophic consequences of their experiencing panic-like symptoms through hyperventilation. An excellent example of such reactions, as well as the constructive way that the therapist handles them, is given by Dattilio and Salas-Auvert (2000) in “the case of Susan”. Nevertheless, hyperventilation symptoms do not always match panic attack symptoms. In such cases the therapist can use other techniques to produce panic-like symptoms. Spinning in a chair, use of fearful imagery, physical exercise, reading paragraphs about a disturbing event, reading paired words where various combinations of bodily sensations and catastrophes are presented (e.g. breathlessness–suffocate, dizziness–fainting, palpitations–dying), visual distortion grids, staring at a blank wall or a blank sheet of paper are some of the procedures the therapist may choose to use for this purpose. Needless to say, the selection of procedures is always based on the possibility each one of them has to produce specific symptoms for the specific patient. Sometimes the therapist has to use his imagination to devise a procedure that matches the patient’s unique panic profile and the idiosyncratic meaning he ascribes to panic sensations and cognitions. The identification of subtle avoidant/escape behaviours helps patient and 114 Gregoris Simos therapist agree on consequent homework assignments. Repeatedly dropping safety behaviours whenever a panic attack occurs will help a patient repeatedly disconfirm his catastrophic misinterpretations and his predictions for the worst happening. Breathing retraining or training in slow breathing gives the patient a pattern of breathing that is incompatible with hyperventilation, something that the patient can use as a coping technique when anxious. Breathing retraining is introduced in the session and then given as homework. Patients are instructed to practise regularly in a slow, smooth and shallow pattern of breathing, with a rate of 8–12 breaths per minute. For this purpose patients can use either their watch – a complete breathing circle in 5 seconds results in a rate of 12 breaths per minute – or a pacing tape. The aim of this procedure is for the patient to become familiar with such a breathing rate without using the tape or his watch, and easily switching to that rate whenever and wherever it is needed. Since patients believe that there is something wrong with their physical health, and depending on the interpretations they make of certain bodily symptoms (for example, palpitations are indicative of a serious cardiac problem), patients selectively attend to their body. Even a slight change in heart rate or a transient light-headedness, sensations probably unnoticed under normal conditions, may thus become the trigger of a panic attack. Manipulating focus of attention during the session by asking the patient to concentrate for a couple of minutes on a specific bodily part or function, and asking the patient to focus on an external situation – e.g. describing a drawing on the wall with every possible detail – are ways of demonstrating the anxiogenic role of selective attention, and also introduce the patient to refocusing techniques. Patient and therapist work together to identify what might have worked for the patient in the past, generate alternatives, and agree on ways for the patient to practise external refocusing techniques until the next session. Significant conclusions arising from this session’s experiences are written down by the patients, and are used either as a homework task where the patient regularly reviews his notes, or in the form of coping cards for appropriate occasions. Session 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Review panic diary and degree of belief in catastrophic misinterpretations. Reaction to last week’s session/conclusions/further conclusions. Review homework. Recent panic scenario/coping techniques. Additional coping skills (refocusing, coping imagery, rational responding). Automatic thoughts. Homework. Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 115 The panic diary helps the review of recent panic attacks. Triggering events, panic attack frequency, panic symptom profile, possibly identified sequences of sensations – thoughts, interpretation of sensations and accompanying thoughts and images, as well as responses to each panic attack – and effective coping or escape behaviours are carefully reviewed. The patient’s reactions to the previous week’s session, and especially reactions to the hyperventilation provocation test and the resulting conclusions are important topics for a detailed discussion. The therapist also reviews homework and the agreed practice and implementation in practice of breathing retraining and refocusing techniques. Instances of successful or unsuccessful use of these techniques are also examined in detail. Drawing a recent panic scenario may also help patient and therapist find and discuss where the patient did use or could have used coping techniques to prevent or arrest a panic attack. Panic induction through the same, or a different, manipulation may also be included in this session, and refocusing techniques are also practised in the session. Brief, threatening images are sometimes triggering or maintaining factors in a panic attack. A feared consequence or outcome may by represented as a dreadful image, and not as a verbal representation in a panic patient’s mind. Such images may have a stereotypical and repetitive nature, while specific images that accompany a panic attack almost invariably stop at their worst moment. Identifying and responding to spontaneous imagery is a significant task for these patients. Restructuring and modifying such an image into a less threatening and less catastrophic image can be done by asking the patient to visualise a more realistic sequence of events. Practising image substitution or image continuation to a non-catastrophic end may result in either the image disappearing or losing its panicogenic effect. Practising coping imagery, both regularly and as soon as a frightening image occurs, becomes part of the homework. In this session the patient is introduced to automatic thoughts and the role they play in emotions, behaviours, and physiological arousal. By using the patient’s automatic thoughts, the therapist reviews the relationship of automatic thoughts to anxiety, and the patient is taught how to identify automatic thoughts. Rationally responding to negative automatic thoughts is introduced as a skill the patient can progressively learn in order to manage unnecessary emotional, behavioural and bodily reactions. Session 4 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Review panic diary and degree of belief in catastrophic misinterpretations. Review homework. Brief treatment review. Subtle avoidance/exposure hierarchy. Practise cognitive skills. Dysfunctional Thought Record (DTR). Homework. 116 Gregoris Simos A brief treatment review is an essential step in this session. Evaluation of progress, data collected to date, and degree of patient’s belief in his catastrophic misinterpretations are extensively discussed. The therapist will probably have to re-conceptualise the patient’s problems in the light of recently collected data. One problem in this stage of treatment, not pertinent to cognitive behaviour therapy only, but to almost any other kind of therapy, is the therapist’s inclination to fit a patient’s problems into the therapist’s theoretical orientation and available treatment options, instead of adjusting his conceptualisation to the patient’s presenting problem. Relevant problems that may already be evident at this stage are those related to the patient’s compliance with assigned homework. Extensive discussion on the patient’s feedback on the way he perceives treatment rationale, the credibility he gives to the conceptualisation of his problem in cognitive behavioural terms, and the way he perceives his progress are essential steps toward resolving such problems. Having already drawn and re-drawn panic scenarios with the patient, and having already reviewed several panic attacks in the panic diary, the therapist may already have clearly identified a patient’s forms of safety and avoidance behaviours. By reviewing a recent panic scenario with the patient, the therapist helps the patient understand the role that safety and avoidant behaviours play in maintaining catastrophic beliefs and consequently panic attacks. The therapist presents his observations not in the form of an unchallenged truth, but as a rather testable hypothesis. This kind of attitude will also effectively help implementation of consequent behavioural experiments. Behavioural experiments can start in session. Induction of anxiety or panic reactions in session through hyperventilation or other techniques, and dropping safety behaviours, is a way to test an agreed hypothesis. For example, the patient who is afraid of dizziness is asked to hyperventilate, reproduce his fearful bodily sensations in a standing position and, instead of letting himself sit down or lean on the wall in order to prevent himself from collapsing, is asked to remain in that position, or even stand on one leg. Specific behavioural experiments targeting specific symptom misinterpretations can be agreed upon with the patient, practised both in session, and as homework assignments. Principles of progressive exposure to feared situations in the case where a panic patient is also agoraphobic are introduced in that session. The way that agoraphobic avoidance maintains fears and prevents disconfirmation of catastrophic predictions is also explained. The patient is also encouraged to enter agoraphobic conditions, try out his new skills for dealing with panic, and also practise and enhance his control and reappraisal techniques. An exposure hierarchy will help patient and therapist devise appropriate exposure assignments as part of the following week’s homework. Having already socialised the patient to negative automatic thoughts, and to rationally responding to them in the previous session, helps the therapist proceed to the verbal challenging of the automatic thoughts part of therapy. Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 117 A necessary tool for this purpose is the Dysfunctional Thought Record (DTR) developed by Judith Beck (1995). The DTR allows patients to monitor (a) situations that trigger automatic thoughts, (b) automatic thoughts, (c) resulting emotions, (d) rational and adaptive responses to automatic thoughts, and (e) related outcomes (change in beliefs and emotional responses). Appropriate questions, like “What evidence do I have for this thought?”, “Is there any alternative explanation?”, or “Am I thinking in allor-nothing terms?”, help patients question the evidence for a particular misinterpretation or validity of specific safety behaviours, explore counterevidence, and adopt alternative appraisals. Rationally responding to automatic thoughts is a skill the patient can learn through continuous reasoning and practice, and appropriate feedback by the therapist. Negative automatic thoughts related to a recent panic attack are dealt with first in session, and also as part of the homework. Sessions 5–12 1 2 3 4 5 6 Review panic diary and degree of belief in catastrophic misinterpretations. Review homework. Dysfunctional beliefs/anxious imagery/cognitive restructuring. DTR. Stresses/problems/problem-solving. Homework. Review of the panic diary and DTRs is an opportunity for continuous work on the reduction of catastrophic misinterpretations. Eliciting and responding to the patient’s idiosyncratic evidence, identifying relevant dysfunctional beliefs, and consequent cognitive restructuring are parts of the ongoing cognitive change process. Panic inductions, behavioural experiments, dropping safety behaviours, exposure to feared situations, use of coping imagery and coping cards, as well as controlled breathing, refocusing, or relaxation, are additional therapeutic techniques. Identification and modification of stressors, management of concurrent real life difficulties, and application of problem-solving techniques, are also possible areas for appropriate interventions. Effects of treatment become evident in the reduction and elimination of panics and general anxiety, reduction and elimination of agoraphobic avoidance, the patient’s increased self-reliance, and ultimately in the patient’s improved quality of life (Telch, Schmidt, Jaimez, Jacquin, & Harrington, 1995). Final sessions also orient patients toward termination of therapy and relapse prevention. Discussion of skills acquired in therapy and the way they can be utilised and applied in the case of future attacks, as well as a jointly developed self-programme for this case, are necessary steps in prevention of 118 Gregoris Simos relapses. Scheduled booster sessions help patient and therapist manage nonanticipated problems, and review maintenance of therapeutic results and further progress. The above structured treatment plan does not include a formal interoceptive exposure (i.e. repeated exposure to feared bodily sensations) procedure, although repeated panic induction in sessions, described above, may also function as such. Recent evidence suggests that the addition of interoceptive exposure to cognitive restructuring and in vivo exposure to agoraphobic situations is more effective than the addition of breathing retraining to cognitive restructuring and in vivo exposure to agoraphobic situations (Craske, Rowe, Lewin, & Noriega-Dimitri, 1997). However, a somewhat contrasting finding was also recently reported (Brown, Beck, Newman, Beck, & Tran, 1997). Focused cognitive therapy (FCT), described above, was compared with standard cognitive therapy (SCT). SCT focused primarily on the cognitions and beliefs relevant to interpersonal concerns involved in generalized anxiety, and contrary to FCT did not include induced in-office panic exposure specific to the patient’s panicogenic cognitions. Both treatment conditions proved equally effective in reducing panic attack frequency, anxiety, and depression, with 89.5% of the SCT group and 84.2% of the FCT group being free of panic attacks at 1-year follow-up. However, for a more detailed description of regular interoceptive exposure see Barlow and Cerny (1988, pp. 151–170). Concluding remarks Although a panic attack may present with a variety of different symptoms, panic attacks seem to have some uniqueness; the six most frequent symptoms reported by a group of 41 agoraphobics with panic from Albany, USA, were palpitations, dizziness, sweating, fear of going crazy or losing control, dyspnoea, and shaking (Barlow & Craske, 1988), while those reported by a similar group of 71 patients from Thessaloniki, Greece, were palpitations, dizziness, fear of dying, dyspnoea, shaking, and tingling sensations (Simos, Bitsios, Dimitriou, & Paraschos, 1995). While the most intense panic symptoms in the Albany group were palpitations, fear of dying, dizziness, trembling, dyspnoea, and hot and cold flushes, the most intense panic symptoms in a similar group of 29 patients from Manchester, UK, were palpitations, hot and cold flushes, sweating, fear of losing control, trembling, and fear of going crazy (Kalpakoglou, 1993). These findings support not only the uniqueness of panic attacks, but also their universality. DSM-IV (APA, 1994) requires 4 symptoms out of a list of 11 physical and 2 cognitive symptoms for the diagnosis of a panic attack. It is obvious from this definition that one can generate 715 possible four-symptom combinations or phenotypic expressions of a panic attack. Some of these symptom clusters may have similarities, if they share two or three common symptoms, but a panic attack characterised by “palpitations, shortness of breath, hot and cold Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 119 flushes, and nausea” is completely different from an attack with “dizziness, trembling, sweating, and depersonalisation” or from an attack with “lightheadedness, chest pain, heart pounding, and fear of losing control”. It is apparent from these examples that DSM-IV leaves quite ample room for non-cognitive panic attacks (330 symptom combinations of the above 715 do not include at least one cognitive symptom), something that may be a weakness of DSM-IV, a weakness of cognitive theory, or a weakness of both, in their conceptualisation of panic. Cox, Swinson, Endler, and Norton (1994) have found a three-factor model of panic symptomatology consisting of dizziness-related symptoms, cardiorespiratory distress, and cognitive factors, and concluded that some symptoms are more likely to be present in a panic attack than others, suggesting thus that the present phenomenological classification (DSM) of panic is rather inaccurate. A second consequence of these numerous panic-symptom profiles is that panic disorder patients may constitute a quite heterogeneous group. As a result, standardised or focused cognitive behaviour therapies for panic disorder cannot have, and actually do not have, a total and unique therapeutic application and success. Cognitive theory of panic has been very influential in the way contemporary therapists understand and treat panic; cognitive behaviour therapy “is a highly effective treatment for panic, with intention-totreat analyses indicating 74–94% of patients becoming panic free and these gains being maintained at follow-up” (Clark, 1997, p. 145). However, there are still 6–26% of panic patients that, although treated by pioneering and highly skilful therapists, remain symptomatic. The recognition that, although CBT is highly effective both in the short and long term, there are still patients who continue to experience some exacerbations and remissions over the long term, creates considerable scepticism (Barlow, 1997). On the other hand, convincing evidence suggests that panic disorder is a chronic and recurring condition, often requiring ongoing maintenance pharmacotherapy (Pollack & Otto, 1997; Davidson, 1998). Finally, sufficient data are not available to determine whether the effects of CBT combined with pharmacotherapy are additive in treating panic disorder, while CBT is not widely offered to patients because of cost considerations (Gelder, 1998). A possible answer to these challenges will perhaps show that there is still something missing, and hopefully a more accurate conceptualisation of panic, as well as more powerful cognitive behavioural treatments for panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, will develop. References American Psychiatric Association (1980). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM-III). Washington, DC: Author. American Psychiatric Association (1987). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised (DSM-III-R). Washington, DC: Author. 120 Gregoris Simos American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: Author. Appleby, I.L., Klein, D.F., Sachar, E.L., & Levitt, M. (1981). Biochemical indices of lactate-induced panic: A preliminary report. In D.F. Klein & J.G. Rabkin (Eds.), Anxiety: New Research and Changing Concepts. New York: Raven Press. Arnz, A., &, van den Hout, M. (1996). Psychological treatments of panic disorder without agoraphobia: cognitive therapy versus applied relaxation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 113–121. Ascher, L.M. (1981). Employing paradoxical intention in the treatment of agoraphobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 19, 533–542. Barlow, D.H. (1990). Long-term outcome for patients with panic disorder treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 51 (Suppl.), 17–23. Barlow, D.H. (1997). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder: current status. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 58 (Suppl. 2), 32–36. Barlow, D.H. & Cerny, J.A. (1988). Psychological Treatment of Panic. New York: The Guilford Press. Barlow, D.H. & Craske, M.G. (1988). The phenomenology of panic. In S. Rachman & J.D. Maser (Eds.), Panic: Psychological Perspectives. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Barlow, D.H. & Wolfe, B.E. (1981). Behavioral approaches to anxiety disorders: A report on the NIMH-SUNY, Albany, research conference. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49, 448–454. Barlow, D.H. Craske, M.G., Cerny, J.A., & Klosko, J.S. (1989). Behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behavior Therapy, 20, 261–282. Beck, A.T. (1976). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. Madison: International Universities Press. Beck, A.T. (1988). Cognitive approaches to panic disorder: theory and therapy. In S. Rachman & J.D. Maser (Eds.), Panic: Psychological Perspectives. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (page 106). Beck, A.T., & Steer, R.A. (1991). Relationship between the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale with anxious outpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 5, 213–223. Beck, A.T., Emery, G., & Greenberg, R.L. (1985). Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Perspective. New York: Basic Books Beck, A.T., Sokol, L., Clark, D.A., Berchick, R., & Wright, F. (1992). A crossover study of focused cognitive therapy for panic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 778–783. Beck, J. (1995). Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York: Guilford Press. Beck, J.S. (1992a). Focused Cognitive Therapy (FCT) for Panic Disorder. Center for Cognitive Therapy, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Beck, J.S. (1992b). Panic Diary. Center for Cognitive Therapy, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Brown, G.K., Beck, A.T., Greenberg, R.L., Newman, C.F., Beck, J., Tran, G., Clark, D., Reilly, N., & Betz, F. (1991, Nov.). The role of beliefs in the cognitive treatment of panic disorder. Poster presented at the Annual AABT Convention, New York. Brown, G.K, Beck, A.T., Newman, C.F., Beck, J.S., & Tran, G.Q. (1997). A comparison of focused and standard cognitive therapy for panic disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 11, 329–345. Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 121 Chambless, D.L., Caputo, G.C., Bright, D., & Gallagher, R. (1984). Assessment of fear of fear in agoraphobics: The Body Sensations Questionnaire and the Agoraphobic Cognitions Questionnaire. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52, 1090–1097. Charney, D.S., Heninger, G.R, & Breier, A. (1984). Noradrenergic function in panic anxiety: Effects of Yohimbine in healthy subjects and patients with agoraphobia and panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42, 751–763. Charney, D.S., Heninger, G.R., & Jatlow, P.I. (1985). Increased anxiogenic effects of caffeine in panic disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42, 233–243. Clark, D.M. (1986). A cognitive approach to panic. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24, 461–470. Clark, D.M. (1988). A cognitive model of panic attacks. In S. Rachman & J.D. Maser (Eds.), Panic: Psychological Perspectives. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Clark, D.M. (1989). Anxiety states: Panic and generalised anxiety. In K. Hawton, P.M. Salkovskis, J. Kirk & D.M. Clark (Eds.), Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Psychiatric Problems: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Clark, D.M. (1996). Panic Disorder: From theory to therapy. In P.M. Salkovskis (Ed.), Frontiers of Cognitive Therapy. New York: Guilford Press. Clark, D.M. (1997). Panic disorder and social phobia. In D.M. Clark & C.G. Fairburn (Eds.), Science and Practice of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Clark, D.M. & Salkovskis, P.M. (1987a). Cognitive Treatment for Panic Attacks: Therapist’s Manual. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford. Clark, D.M. & Salkovskis, P.M. (1987b). The Physiology of Hyperventilation/Coping with a Panic Attack. Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford. Clark, D.M., Salkovskis, P.M., & Chalkley, A.J. (1985). Respiratory control as a treatment of panic attacks. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 16, 23–30. Clark, D.M., Salkovskis, P.M., Hackmann, A., Middleton, H., Anastasiades, P., & Gelder, M. (1994). A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation and imipramine in the treatment of panic disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 759–769. Cox, B.J., Swinson, R.P., Endler, N.S., & Norton, G.R. (1994). The symptom structure of panic attacks. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 35, 349–353. Craske, M.G., & Barlow, D.H. (1993). Panic disorder and agoraphobia. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.), Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders/ Second Edition. New York: Guilford Press. Craske, M.G., Brown, T.A., & Barlow, D.H. (1991). Behavioral treatment of panic disorder: A two-year follow-up. Behavior Therapy, 22, 289–304. Craske, M.G., Rowe, M., Lewin, M., & Noriega-Dimitri, R. (1997). Interoceptive exposure versus breathing retraining within cognitive-behavioural therapy for panic disorder with agoraphobia. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36, 85–99. Cullington, A., Butler, G., Hibbert, G., & Gelder, M. (1984). Problem solving: Not a treatment for agoraphobia. Behavior Therapy, 15, 280–286. Dattilio, F.M. & Salas-Auvert, J.A. (2000). Panic Disorder: Assessment and Treatment through a Wide-angle Lens. Pheonix, AZ: Zieg, Tucker & Co. 122 Gregoris Simos Davidson, J.A.R. (1998). The long-term treatment of panic disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59 (Suppl.8), 17–21. Ehlers, A., Margraaf, J., Roth, W.T., Taylor, C.B., & Birbaumer, N. (1988). Anxiety induced by false heart rate feedback in patients with panic disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 26, 1–11. Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. Sacaucus, NJ: Lile Stuart. Emmelkamp, P.M.G., & Kuipers, A.C.M. (1979). A follow-up study four years after treatment. British Journal of Psychiatry, 134, 353–355. Emmelkamp, P.M.G., & Mersch, P.P. (1982). Cognition and exposure in vivo in the treatment of agoraphobia: Short-term and delayed effects. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6, 77–88. Emmelkamp, P.M.G. Brilman, E., Kuiper, H., & Mersch, P.P. (1986). The treatment of agoraphobia: A comparison of self-instructional training, Rational Emotive Therapy, and exposure in vivo. Behavior Modification, 10, 37–53. Emmelkamp, P.M.G., Kuipers, A.C.M., & Eggeraat, J.B. (1978). Cognitive modification versus prolonged exposure in vivo: A comparison with agoraphobics as subjects. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 16, 33–41. Emmelkamp, P.M.G., van der Hout, A., & de Vries, K. (1983). Assertive training for agoraphobics. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21, 63–68. Gelder, M.G. (1998). Combined pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18 (Suppl. 2), 2–5. Gelder, M.G., & Marks, I.M. (1966). Severe agoraphobia: A controlled prospective trial of behaviour therapy. British Journal of Psychiatry, 112, 309–319. Goisman, R.M., Warshaw, M.G., Peterson, L.G., Rogers, M.P., Cuneo, P., Hunt, M.F., Tomlin-Albanese, J.M., Kazim, A., Gollan, J.K., Epstein-Kay, T, Reich, J.H., & Keller, M.B. (1994). Panic, agoraphobia, and panic disorder with agoraphobia: Data from a multicenter anxiety disorders study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease,182, 72–79. Goldstein, A.J. & Chambless, D.L. (1978). A reanalysis of agoraphobia. Behavior Therapy, 9, 47–59. Greenberg, R.L. (1989). Panic disorder and agoraphobia. In J.M.G. Williams & A.T.Beck (Eds.), Cognitive Therapy in Clinical Practice: An Illustrative Casebook. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Greenberg, R.L. & Beck, A.T. (1987). Panic Attacks: How to Cope, How to Recover. Center for Cognitive Therapy, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Hoffart A. (1993). Cognitive treatments of agoraphobia: A critical evaluation of theoretical basis and outcome evidence. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 7, 75–91. Jacobson, N.S., Wilson, L., & Tupper, C. (1988). The clinical significance of treatment gains resulting from exposure-based interventions for agoraphobia: A reanalysis of outcome data. Behavior Therapy, 19, 539–554. Jansson, L. &, Ost, L-G. (1982). Behavioral treatments for agoraphobia: An evaluative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 2, 311–336. Kalpakoglou, T. (1993). Generalized anxiety and panic disorder: cognitivebehavioural group therapy. PhD Thesis, Victoria University of Manchester, England. Kendall, P.C. & Ingram, R.E. (1987). The future of cognitive assessment of anxiety: Let’s get specific. In L. Michelson & L.M. Ascher (Eds.), Anxiety and Stress Cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder 123 Disorders: Cognitive-behavioral Assessment and Treatment. New York: The Guilford Press. Klein, D.F. (1964). Delineation of two drug responsive anxiety syndromes. Psychopharmacologia, 5, 397–408. Klein, D.F. (1967). Importance of psychiatric diagnosis in prediction of clinical drug effects. Archives of General Psychiatry, 16, 118–126. Klein, D.F. (1981). Anxiety reconceptualized. In D.F. Klein & J. Rabkin (Eds.), Anxiety: New Research and Changing Concepts. New York: Raven Press. Liebowitz, M.R., Gorman, J.M., Fyer, A.J., Levitt, M., Dillon, D., Levy, G., Appleby, I.L., Anderson, S., Palij, M., Davies, S.O., & Klein, D.F. (1985). Lactate provocation of panic attacks: II. Biochemical and physiological findings. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42, 709–719. Marchione, K., Michelson, L., Greenwald, M., & Dancu, C. (1987). Cognitive behavioral treatment of agoraphobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 25, 319–328. Margraaf, J., Barlow., D.H., Clark, D.M., & Telch, M.J. (1993). Psychological treatment of panic: Work in progress on outcome, active ingredients, and follow-up. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31, 1–8. Marks, I.M. (1978). Living with Fear. New York: McGraw-Hill. Marks, I.M. (1987). Fears, Phobias, and Rituals. New York: Oxford University Press. Marks, I.M., Gelder, M.G., & Edwards, G.G. (1968). Hypnosis and desensitisation for phobias: A controlled prospective trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 114, 1263–1274. Mavissakalian, M., Michelson, L., Greenwald, D., Kornblith, S., & Greenwald, M. (1983). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of agoraphobia: Paradoxical intention vs. self-statement training. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21, 75–86. McNally, R.J. (1994). Panic Disorder: A Critical Analysis. New York: Guilford Press. McPherson, F.M., Brougham, L., & McLaren, S. (1980). Maintenance of improvement in agoraphobic patients treated by behavioural methods – A four-year follow-up. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 18, 150–152. Meichenbaum, D. (1977). Cognitive-Behavior Modification. New York: Plenum Press. Michelson, L., Mavissakalian, M., & Marchione, K. (1988). Cognitive behavioral and psychophysiological treatments of agoraphobia: A comparative outcome investigation. Behavior Therapy, 19, 97–120. Moras, K, Craske, M., & Barlow, D. (1990). Behavioral and cognitive therapies for panic disorder. In R. Noyes Jr, M. Rorth, & G.D., Burrows (Eds.), Handbook of anxiety, Vol. 4: The Treatment of Anxiety. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers. Munby, M. & Johnston, D.W. (1980). Agoraphobia: The long-term follow-up of behavioural treatment. British Journal of Psychiatry, 137, 418–427. Newman, C.F. (1992). Cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders. In B. Wolman (Ed.), Anxiety and Related Disorders: A Handbook. New York: Wiley Newman, C.F. & Haaga, D.A.F. (1992). Cognitive skills training. In W. O’Donohue & L. Krasner (Eds), Handbook of Skills Training. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press. Ost, L-G. & Westling, B.E. (1995). Applied relaxation vs cognitive behaviour therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 145–158. Pollack, M.H. & Otto, M.W. (1997). Long term course and outcome of panic disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 58 (Suppl. 2), 57–60. Rachman, S. (1991). The consequences of panic. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 5, 187–197. 124 Gregoris Simos Rachman, S. & de Silva P. (1996). Panic Disorder: The Facts. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rainey, R.M., Pohl, R.B., Williams, M., Knitter, E., Freedman, R.R., & Ettedgui, E. (1984). A comparison of lactate and isoproterenol anxiety states. Psychopathology, 17, (Suppl. 1), 74–82. Salkovskis, P.M. (1991). The importance of behaviour in the maintenance of anxiety and panic: A cognitive account. Behavioural Psychotherapy, 19, 6–19. Salkovskis, P.M., Clark, D.M., & Gelder M.G. (1996). Cognition-behaviour links in the persistence of panic. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 453–458. Salkovskis, P.M., Jones, D.R.O., & Clark, D.M. (1986). Respiratory control in the treatment of panic attacks: Replication and extension with concurrent measurement of behaviour and pCO2. British Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 526–532. Simos, G. (1991). Understanding Anxiety (in Greek). CMHC, 2nd Department of Psychiatry, Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece. Simos, G., Bitsios, P., Dimitriou, E., & Paraschos A. (1995, July). Panic attacks in panic disorder with and without agoraphobia: Different symptom profiles? Poster presentation at the World Congress of Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies, Denmark. Simos, G., Dimitriou, E., Vaiopoulos, C., & Paraschos, A. (1994, Sept.). Does medical knowledge influence catastrophic anxiety cognitions? 24th Congress of the European Association for Cognitive and Behavioural Psychotherapy, Corfu, Greece. Sokol, L., Beck, A.T., Greenberg, R.L., Wright, F.D., & Berchick, R.J. (1989). Cognitive therapy of panic disorder. A nonpharmacological alternative. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 177, 711–716. Taylor, S. (2000). Understanding and Treating Panic Disorder. Cognitive-behavioural Approaches. Chichester: Wiley. Telch, M.J., Schmidt, N.B., Jaimez, T.L., Jacquin, K.M., & Harrington, P.J. (1995). Impact of cognitive-behavioral treatment on quality of life in panic disorder patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 823–830. Uhde, T.W., Roy-Byrne, P.P., Vittone, B.J., Boulenger, J.P., & Post, R.M. (1985). Phenomenology and neurobiology of panic disorder. In A.H. Tuma & J.D. Maser (Eds.), Anxiety and the Anxiety Disorders. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. van den Hout, M., Arntz, A., & Hoekstra, R. (1994). Exposure reduced agoraphobia but not panic, and cognitive therapy reduced panic but not agoraphobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 32, 447–451. van den Hout, M.A. & Griez, E. (1984). Panic symptoms after inhalation of carbon dioxide. British Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 503–507. Warren, R., Zgouridis, G., & Englert, M. (1990). Relationships between catastrophic cognitions and body sensations in anxiety disordered, mixed diagnosis, and normal subjects. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28, 355–357. Wells, A. (1997). Cognitive Therapy of Anxiety Disorders: A Practical Manual and Conceptual Guide. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons. Williams, S.L. & Rappoport, A. (1983). Cognitive treatment in the natural environment of agoraphobics. Behavior Therapy, 14, 299–313. Chapter 5 Psychosocial treatment for OCD Combining cognitive and behavioural treatments Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is no longer seen as a problem that is untreatable. In the 30 years since behavioural treatments for OCD were introduced (Meyer, 1966) they have become the psychosocial treatment of choice (Foa & Franklin, 1998). Foa and Kozak (1996) reported that 83% of people who completed treatment benefited from it. Of those studies that reported long-term treatment outcome (i.e., an average of 2.5 years), 79% of people continued to be considered treatment responders (Foa & Kozak, 1996). Medications given alone or in combination with exposure and response prevention (ERP) are not more effective than ERP alone (Foa, Franklin, & Kozak, 1998). Given the high rate of relapse associated with medication withdrawal (Pigott & Saey, 1998) there is some suggestion that ERP is a more cost-effective treatment (Foa, Franklin, & Kozak, 1998) for OCD sufferers. As there are variations in how ERP is conducted, Abramowitz (1996) reported that effect sizes for ERP were larger when the treatment was conducted with the aid of a therapist as opposed to being self-directed, involved complete and not partial response prevention, and included both in-vivo and imaginal exposure. Despite the promising treatment outcomes associated with ERP, a number of caveats must be considered which include residual symptoms, treatment refusal/dropout, and treatment non-response. Moreover, ERP is not particularly helpful with obsessions in the absence of overt compulsions (Salkovskis & Westbrook, 1989; Rachman, 1983). Salkovskis and Westbrook (1989) reported that in a review of seven studies, using 50% decline in symptom severity as a cut-off to separate improved from not improved, only 46% of the subjects met that criterion. Rachman (1983) suggested that the difficulty behaviour therapists encountered when working with “pure” obsessionals (as opposed to obsessive-compulsives) was due to a technical failure and a lack of effective therapeutic strategies. In their review of treatment efficacy in OCD, Foa, Steketee, and Ozarow (1985) used a 30% decline in symptom severity pre- to post-treatment to differentiate those who benefited from treatment from those who did not. Foa et al. (1985) reported that approximately half of the subjects reported at least a 126 Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean 70% decline in symptoms and approximately 40% reported a moderate response to treatment. The remaining subjects, approximately 10%, did not benefit from treatment (i.e., less than 30% decline in symptoms). Although these figures are impressive, they also indicate that some people are leaving treatment with considerable residual symptoms. In a review of follow-up studies, O’Sullivan and Marks (1991) reported that 1–6 years following treatment, subjects reported an average of 60% decline in symptoms compared to pre-treatment severity. Although it is encouraging that treatment gains are maintained long after completion of treatment, it also suggests that further improvements are not made and that people continue to live with residual symptoms. Moreover, as an indirect indicator of continued impairment following treatment, O’Sullivan and Marks (1991) reported that approximately 33% of the sample sought treatment for comorbid depression and approximately 15% received further treatment for their OCD. For some people ERP can be difficult to tolerate. Stanley and Turner (1995) reported that 20–30% of people either refuse to commit to treatment or drop out after treatment has been initiated. When drop-outs and refusers are considered, the conservative estimate of those people who will respond to treatment decreases to 63% at post-treatment and 55% at follow-up (Stanley & Turner, 1995). Despite the substantial percentage of people who either do not respond to treatment or terminate prematurely, there have been no consistent predictors of failure or drop-out. Variables that have been investigated include pretreatment severity, duration of disorder, age of onset, severity of comorbid depression, overvalued ideation, treatment expectancies, homework compliance and the presence of personality disorders (Foa, Franklin, & Kozak, 1998; Stanley & Turner, 1995). Rachman and Hodgson (1980) reported that “OCD lifestyle” was the only factor that predicted a negative outcome. Given that it was independent of severity, the extent to which an individual’s life revolved around his/her OCD was a negative predictor of treatment outcome. A cognitive alternative to ERP Salkovskis (1985) proposed a cognitive theory of OCD that has stimulated research in the area. Although he is not the first to suggest the importance of a cognitive conceptualisation of intrusive thoughts (e.g., Carr, 1974; McFall & Wollersheim, 1979), the theory put forward by Salkovskis has been the most comprehensive to date and has stimulated a great deal of subsequent research. The cornerstone of the cognitive model rests on the premise that intrusive thoughts are essentially a universal human experience. Rachman and de Silva (1978) initially reported that over 90% of a community sample reported occasional intrusive, repugnant, unwanted thoughts, images, or impulses. Salkovskis Psychosocial treatment for OCD 127 and Harrison (1984) replicated this finding. The intrusions reported by the non-clinical sample did not differ in content from those experienced by people diagnosed with OCD. However, what did differ was the meaning attributed to the intrusive thought. People without OCD appraised these intrusive thoughts as having no special significance, whereas people diagnosed with OCD appraised these thoughts as threatening and personally relevant. According to Salkovskis (1985), the threat simultaneously produces emotional distress and the urge to engage in overt or covert compulsive behaviour that functions to reduce the threat. For example, a common intrusive thought reported in Rachman and de Silva’s (1978) sample was the thought of one’s family being killed in a car accident. A nonOCD person would not place any special significance on that thought but somebody with OCD may appraise the same thought as indicative of future danger and to ignore it would be tantamount to causing the car crash. This threatening appraisal would clearly lead to anxiety and the urge to warn family members about the danger associated with automobile travel. The threatening appraisal is what maintains the behaviour; without it, the emotional distress would be minimal or non-existent and the urge to engage in a behaviour that functions to decrease the threat would be unnecessary. Given the pivotal importance of the appraisal process, it is the target of cognitive behavioural treatment and will be discussed in detail in later sections of the chapter. In the initial theoretical paper, Salkovskis (1985) discussed the advantages of his theory and treatment in terms of the disadvantages associated with ERP, namely the high drop-out and refusal rate. He reasoned that a treatment that did not rely so heavily upon exposure and habituation would be less taxing upon patients and would lead to lower drop-out rates. More importantly, cognitive treatment allows therapists to focus on appraisals and the underlying beliefs thought to be precursors to appraisals that may remain unaddressed in a purely behavioural paradigm. Salkovskis (1985) reasoned that the appraisals thought to be of central importance are those that focus on responsibility. Although there have been various definitions of responsibility, Salkovskis (1996) regards responsibility as “the belief that one has power which is pivotal to bring about or prevent subjectively crucial negative outcomes”. In the above example of the car accident, Salkovskis would say that the threat associated with intrusive thought is not the possibility of the car accident, but rather the appraisal that the OCD person would feel, or fear being held, responsible for the outcome because he or she did not act on the thought. The function of the compulsive behaviour (i.e., warning the family) decreases the possibility of being held responsible. The theory has been modified (Salkovskis, 1996) and expanded but the central thesis, responsibility appraisals driving behaviour, has been retained. 128 Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean Other belief domains in OCD Other theorists have suggested additional appraisals aside from inflated responsibility that may function to maintain obsessive compulsive behaviour. For example, the Obsessive-Compulsive Cognitions Working Group (OCCWG), an international group of researchers in OCD, have suggested five appraisal domains in addition to responsibility (OCCWG, 1997). Specifically, the beliefs thought to be important are (1) overimportance of thoughts, (2) excessive concern about the importance of controlling one’s thoughts, (3) overestimation of threat, (4) intolerance of uncertainty, and (5) perfectionism (OCCWG, 1997). Overimportance of thoughts Overimportance of thoughts has also been discussed by other researchers (e.g., Freeston, Rheume, & Ladouceur, 1996; McFall & Wollersheim, 1979; Shafran, Thordarson, & Rachman, 1996) and can be summarised as giving a thought merit because it was experienced (i.e., the thought was important, which is why it occurred and it is thought about because it is important). The reasoning behind overimportance of thoughts is circular and is easily illustrated using a variety of examples (e.g., fresh food is in high demand and it is in high demand because it is fresh). An additional concept is thought–action fusion (TAF) (Rachman & Shafran, 1997; Shafran, Thordarson, & Rachman, 1996). As the name suggests, TAF is thought to be operating when thoughts and actions are inappropriately fused together. There are two suggested components to TAF: (1) moral TAF and (2) likelihood TAF. In moral TAF, having the thought and engaging in the action are seen as the same (e.g., having an unwanted, unacceptable sexual intrusion is equivalent to carrying out the act). Likelihood TAF entails a higher probability of an event happening because the thought occurred (e.g., the probability of a car crash increases because of an intrusive thought of a loved one dying in an automobile accident). Both moral and likelihood TAF can be associated with guilt and shame and can co-occur within the same person and in response to the same trigger. For example, after a recent US school massacre, a patient with aggressive obsessions experienced both moral and likelihood TAF. He drew a comparison between himself and the boys who did the killing and used the massacre as evidence that, without great resistance on his part, when he experienced aggressive obsessions, he could lose control of his behaviour and begin randomly killing people (likelihood TAF). And because of the likelihood TAF, he continued to view himself as evil for having the aggressive intrusions (moral TAF). An extreme version of TAF is the reasoning process that accompanies the subgroup of OCD people who engage in magical thinking (e.g., unless the lights are turned on and off five times when leaving a room, someone will Psychosocial treatment for OCD 129 die). The implicit appraisal in overimportance of thoughts is responsibility (the responsibility for the outcome in a particular situation rests with the person who initially experienced the thought). However, amongst others, Freeston et al. (1996) agree that there may be some merit, both theoretical and practical, in separating overimportance of thoughts from inflated responsibility. Control over thoughts A concept that is similar to overimportance of thoughts and TAF is the perceived need for control over thoughts. Clark and Purdon (1993) reported a correlation between the inability to control/dismiss thoughts and the frequency and severity of intrusions. The distress is hypothesised to be produced by the perceived catastrophic consequences if the intrusive thought is not controlled (Clark & Purdon, 1993). A typical response to thoughts that are perceived as uncontrollable is an effort to suppress the thought. This strategy has been demonstrated to further increase the frequency of unwanted thoughts (Purdon, 1999; Wegner, 1989), which further increases the use of suppression and so on. Overestimation of threat Overestimation of threat, the tendency to predict negative consequences more so than others, is a cognitive style that may be a common denominator across the anxiety disorders (Salkovskis, 1991). It has been suggested that a faulty reasoning process is at the heart of threat overestimation (Foa & Kozak, 1986). Specifically, most people assume that a situation is not dangerous until it is proven otherwise whereas people with OCD (and perhaps all those with an anxiety disorder) assume danger until it is demonstrated that a situation is proven to be safe. Within OCD, some investigators have differentiated between overpredicting the occurrence of the event and overpredicting the awful consequences associated with the event (van Oppen & Arntz, 1994). These authors reiterated that risk = chance × consequence and to adequately reduce risk, both chance and consequence must be addressed. Van Oppen and Arntz (1994) further suggested that issues of responsibility underlie the unacceptable consequences that might be inflating perceived risk. Thus, appropriate cognitive therapy for OCD would target danger and responsibility. As threat overestimation may be a common cognitive process in the anxiety disorders, lasting therapeutic change may depend upon challenging those appraisals that may be unique to OCD (e.g., overimportance of thoughts and need to control thoughts). Intolerance of uncertainty Although it is a feature of other anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder) it has long been acknowledged to be part of OCD (e.g., Carr, 1974; 130 Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean McFall & Wollersheim, 1979) in that it is difficult for people to make decisions secondary to certainty concerns. It is commonplace for people with OCD to report that they know the behaviour (e.g., locking the door) was done as they watched themselves lock the door. However, because it doesn’t “feel right” or they are not absolutely certain, the behaviour must be repeated (“it’s almost as if I don’t believe what I see or hear” (the locked door or the deadbolt turning)). For people with OCD and perhaps other anxiety disorders, it appears that even the smallest seed of doubt is unacceptable, likely due to the consequences associated with being uncertain (e.g., the door being left unlocked creating an easy entry for a thief). Again, the underlying appraisal that may make uncertainty particularly intolerable is responsibility. Perfectionism Striving for perfection is not unique to OCD and has been hypothesised to be a significant factor in eating disorders (Srinivasagam, Kaye, Plotnicov, Greeno, Weltzin, & Rao, 1995), depression (Hewitt & Flett, 1991, 1993), and other anxiety disorders (Antony, Purdon, Huta, & Swinson, 1998). However, with respect to OCD, the role of perfectionism is evident in people with symmetry/exactness compulsions, cleaning that is not contamination driven, and more subtly in the need to know (e.g., the OCD patient who obsessed about the meaning of life and the necessary components to be happy). The cognitive domains presented in the preceding paragraphs reflect those thought to be important according to the OCCWG (1997). It is possible that other cognitive domains are significant but as yet unidentified. It is also evident that the domains discussed thus far are not mutually exclusive. The importance of the various cognitive domains awaits empirical validation. However, the hypothesised cognitive domains are prominently featured in the cognitive behavioural treatment of OCD, which is described below. The overlap between the cognitive and behavioural approaches Prior to discussing the specific techniques associated with a cognitive behavioural approach to OCD, it is necessary to discuss the common denominator, exposure. Although exposure is common to both a purely behavioural and a cognitive behavioural treatment, the function and duration of it varies. In a behavioural paradigm, exposure is the primary tool used to alter dysfunctional behaviour. OCD is thought to be maintained by the escape from and avoidance of anxiety, which is accomplished by typically overt, and occasionally covert, compulsions. Allowing the person to tolerate gradually more intense levels of anxiety by preventing the completion or initiation of Psychosocial treatment for OCD 131 compulsions and allowing the individual to observe that anxiety habituates both within and between exposures has been the core of behavioural treatments. Exposure also plays a role in cognitive behavioural treatments, but it is one of many tools that therapists have at their disposal to change appraisal and is used primarily to disprove feared consequences. As will be described, the goal of cognitive behavioural treatment (CBT) for OCD is to give the patient alternative(s) regarding how they interpret/appraise their intrusive thoughts. Having patients engage in behavioural experiments to test their appraisals is only one of the many avenues therapists can utilise. What is implied by the difference between the treatments is the centrality of anxiety. In the behavioural model, anxiety is the driving force behind the behaviour. In the cognitive behavioural model, anxiety plays a role but it is secondary to appraisal; the emotion experienced is epi-phenomenal to the interpretation provided by the individual. Foa and colleagues (e.g., Foa & Franklin, 1998; Foa, Franklin, & Kozak, 1998) have stated that the differences between behavioural (i.e., ERP) and cognitive behavioural treatments are essentially moot as therapists appropriately trained in ERP routinely discuss probability overestimation and risk assessment in an effort to alter patient’s beliefs. In our view the differences between ERP and CBT therapies are clear. As we will demonstrate, CBT for OCD is complex and requires a primary focus on appraisal. Exposure is a small but important part of CBT and is conceptualised as one of many possible tools to use to change appraisal/beliefs. We aim to establish that there is much more to CBT for OCD than discussing risk assessment and probability overestimation in the context of exposure. Having stated the difference between the therapies, it has yet to be established if they produce outcomes that are significantly different. It is possible that CBT and ERP may reach a common therapeutic end point having used alternative routes to get there. Guiding principles of treatment The principles of CBT, collaborative empiricism, guided discovery, and Socratic questioning, form the foundation of CBT with OCD sufferers. It is crucial in the initial sessions to establish a working alliance with patients. This working alliance continues throughout therapy as the clinician endeavours to provide an alternative interpretation(s) of the intrusive thoughts rather than disconfirm the OCD interpretations/appraisals. The goal is to provide patients with some flexibility in how they view their triggers and how they interpret their intrusive thoughts. Use of the guiding principles of CBT may prevent the clinician from adopting an argumentative stance with patients (i.e., debating the validity of the intrusive thoughts). The social psychological literature is replete with data suggesting that arguing for or 132 Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean having to support your opinion in a debate functions to strengthen that opinion. Likewise, collaborative empiricism begins during the assessment and continues throughout the duration of the treatment. The clinician’s job during the assessment is to provide a conceptualisation of the OCD that is agreeable to the patient and establishes the importance of one or more of the cognitive domains discussed above. As is true for panic disorder (Cox, Fergus, & Swinson, 1994), understanding and agreeing with the cognitive behavioural conceptualisation of the disorder and the treatment rationales that come from the theory is probably an important component in a successful treatment. If patients understand/accept the model for treatment, it is likely that they will be more active in challenging OCD appraisals. Guided discovery as established through Socratic questioning is a tool that therapists can use to establish and maintain the working alliance. Rather than a didactic style, the collaborative relationship can be protected by guiding patients to their own answers with a series of questions. For example, rather than telling patients the definitions of obsessions and compulsions, they should be asked to identify characteristics that would describe obsessions and compulsions, the form in which they are experienced (thoughts, images, and/or impulses) and examples of each from their own OCD. Allowing patients to reach their own conclusions is probably more powerful than directly supplying the information. The goal of the clinician during treatment is to teach the patient to be his or her own therapist. A Socratic style may be more beneficial than a didactic style in allowing patients to continue to help themselves after treatment is completed. Trigger Faulty appraisals Intrusive thought 1. Overimportance of thoughts 2. Overestimations of danger 3. Overestimations of the consequences of danger 4. Inflated responsibility 5. Overestimations of the consequences of responsibility 6. Need for certainty and control over thoughts Appraisal OCD maintained by failure to evaluate and consider alternative appraisals and beliefs in light of contrary experience Urge to neutralise Distress Figure 5.1 Cognitive behavioural model of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychosocial treatment for OCD 133 Cognitive behavioural treatment strategies for OCD The initial sessions: presentation of the model and treatment rationale and identifying appraisals Following a thorough assessment regarding the extent and severity of the OCD, the first task of treatment is to provide patients with an alternative in conceptualising their symptoms using a cognitive behavioural model (Figure 5.1). Although we use a template when describing the model, the explanation must be idiosyncratic to the patient’s intrusive thoughts, appraisals, and compulsions. As with all subsequent interventions, the information that we provide is presented as a possibility. We never imply or directly state that patients are wrong in their thinking and that we are right, but rather that there is an alternative. In the case of a man who has contamination fears, a typical trigger might be touching money or something in public. Touching these items would likely trigger intrusive thoughts about contamination which is, according to the cognitive behavioural model, followed by an appraisal or interpretation about the possible meaning of being contaminated (e.g., “I’ll pass it on to my children and it will be my fault when they get sick”). As a consequence of this threatening, personally relevant appraisal, the person feels emotional distress (typically anxiety but sometimes guilt, shame, or anger) and the compulsive urge to check to decrease the threat. Once the threat has been neutralised by checking the anxiety decreases. In the above example, engaging in the compulsion functions as a reward in that it allows the OCD person to avoid being responsible for a fire or break-in, which subsequently reduces the anxiety. The OCD person learns that to continue to avoid being responsible for potential catastrophic consequences these compulsive behaviours must be completed when similar appraisals arise in the future. In the absence of contradictory information, OCD patients use their “rewarding non-punishment” (Salkovskis, 1985) as evidence that the situation is indeed dangerous and requires their attention and action. For example, with a doubter/checker, assuming no break-ins or fires and thus nothing for which to feel responsible, they would tend to assume it was due to their efforts at checking and that they should continue to be vigilant and continue to check. After explaining the model the next logical step is to discuss the rationale for treatment. Given that intrusive thoughts are nearly universal (Rachman & de Silva, 1978; Salkovskis & Harrison, 1984) the obsessions are not the target for treatment. It would be impossible to stop thoughts that are a normal experience of being human. However, it is reasonable to target the way in which these intrusive thoughts are interpreted (i.e., appraisals). By way of illustrating the importance of the appraisal process, the patient and therapist collaborate on a non-threatening appraisal that may serve as an alternative to the previously identified OCD appraisal (e.g., responsibility for a fire or 134 Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean break-in would be shared among members of the household and/or the perpetrator). Assuming the patient believes this alternative appraisal (the therapist should acknowledge that they know that the patient does not believe it now, at the beginning of treatment, but if they believed it), the urge to engage in the compulsion and the distress would decrease. Throughout treatment therapists should take every opportunity to normalise the patient’s behaviour, beginning with emphasising the ubiquity of intrusive thoughts. We routinely ask patients to conduct a survey of the frequency of intrusive thoughts amongst their friends and/or family members. To accomplish this task we provide patients with multiple copies of a list of intrusive thoughts reported by a non-clinical sample (Rachman & de Silva, 1978). In session, if the therapist is comfortable, he or she can complete the list with the patient and identify his or her own intrusions. The more people and the wider the variety of people (e.g., peers, people in authority) that complete the list, the more this may aid the patient in realising that experiencing occasional unwanted, repugnant, intrusive thoughts is normal. Explaining the differences between the frequency, intensity, and severity of the thoughts experienced by OCD people and those without OCD, which are all higher in the former group, can be done using the model and emphasising the importance of the appraisal. If an intrusive thought is experienced but appraised in a non-threatening way, there will be no need to attend to it in the future or prevent it from occurring. On the other hand, the same intrusion that is associated with a threatening appraisal can lead to a compulsion, an effort to suppress, distract, or avoid future occurrences of the thought. These strategies, which seem useful in the short term, are damaging in the long term in that they increase the frequency, intensity, and severity of intrusive thoughts. The list of intrusive thoughts reported by a non-clinical sample can have an additional purpose. There will invariably be items on the list that the patient has experienced, but not frequently. The appraisals associated with these intermittent intrusive thoughts would likely be non-threatening and contain no personally relevant meaning. The appraisals associated with infrequent intrusive thoughts can be compared to the appraisals associated with obsessional intrusive thoughts to demonstrate the pivotal role of the appraisal process. As with CBT in other disorders, the first skill to be mastered is identifying the appraisals as they occur during an episode of obsessive compulsive behaviour. Monitoring appraisals and differentiating them from intrusive thoughts is a typical homework assignment that is given after the first treatment session. Accurately identifying appraisals and differentiating them from intrusions often requires a few attempts, as it can be a difficult concept for patients to understand. However, once the initial appraisals are identified, it is often instructive to complete a downward arrow, a process of successive questioning, to identify additional appraisals and/or the core feared consequences. Completing downward arrows can often be difficult for patients as the Psychosocial treatment for OCD 135 Initial Appraisal Not organising receipts would lead to financial mayhem and irresponsible spending ⇓ If that were true, what would it mean to me? I would be an irresponsible person ⇓ If that were true, what would it mean to me? I would be reckless and stupid ⇓ If that were true, what would it mean to me? I’d lose my apartment, car, etc. ⇓ If that were true, what would it mean to me? Become a homeless person – down and out ⇓ If that were true, what would it mean to me? I’d be a failure Figure 5.2 Downward arrow of a man obsessed with accuracy. material can be either emotional or hard to access as the information that is uncovered is often material that patients typically avoid. Figure 5.2 illustrates a downward arrow completed with a man who was obsessed with accuracy and as a result engaged in a number of behaviours that included saving and cataloguing receipts, recording his weight, the room temperature, his urine output, organising his belongings to maximise efficiency, and extensively researching a product prior to purchasing it. The downward arrow often produces other appraisals that need to be addressed that may have otherwise been unidentified. For example, in the example presented in Figure 5.2 two themes are apparent: inflated responsibility and the overriding theme of perfectionism. Introduction of the downward arrows is typically done in session 2. Rather than provide a session by session outline, which can be difficult to accomplish, given the idiosyncratic nature of OCD and the associated appraisals, we will provide strategies to cognitively challenge the various cognitive domains (e.g., overimportance of thoughts, need to control thoughts, etc.). In a recent treatment outcome study completed at our centre, we used the outline listed in Table 5.1 to direct our treatment. As indicated in Table 5.1, the first two sessions are relatively standard, with the first one involving presentation of the model, treatment rationale, and 136 Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean Table 5.1 Overview of CBT for OCD Session 1 Establish goals OCD education Review CBT model and treatment rationale Assess patient understanding of intrusions versus appraisals (provide written examples of each) Homework – self-monitoring of intrusions and appraisals Session 2 Review model and treatment rationale Review homework Introduce general cognitive errors and relation to appraisals Identification of core fears using the downward arrow technique Homework – self-monitoring of intrusions and appraisals and completing a downward arrow for each OCD appraisal Sessions 3–7 Review model and homework Introduction and discussion of one of the belief domains (e.g., overimportance of thought, inflated responsibility) and potential challenge strategies Identifying alternative appraisals that are typically not as threatening as the original OCD appraisal Collaborating on homework – specific assignment is idiographic and typically involves a behavioral experiment and/or other strategies that assist in reappraisal (e.g., survey, information from an expert, etc.) Sessions 8–10 Review of the model and homework Review of OCD appraisals and challenge strategies discussed to date Identification and discussion of OCD assumptions/beliefs Challenging OCD assumptions/beliefs and development of alternative assumptions/beliefs Homework – behavioural experiments to gather evidence for and against alternative assumptions/beliefs Sessions 11–12 Review model and homework Review treatment to date Transition to being own therapist (e.g., what to do when an intrusion is experienced) Relapse prevention Collaborating on homework (session 11 only) introduction to appraisal monitoring. Goal setting also occurs in the first session. Patients are asked to establish a minimal level of decline in symptom severity for which they would consider treatment a success. They are discouraged from expecting to be “cured” of their OCD and encouraged to adopt a management stance. Specifically, patients are told to expect a decline in severity, but that at the termination of treatment there will likely be remaining Psychosocial treatment for OCD 137 symptoms. However, they will have the skills to continue to help themselves after treatment is completed (i.e., function as their own therapist). The second session involves review of the model and treatment rationale and clarifying problems encountered with the previous week’s homework. As time usually permits in a 50–60 minute session, downward arrows are introduced and one is completed in treatment. The third session, as do the remaining sessions, begins with a review of the model and homework. Prior to beginning the cognitive challenging of appraisals, the various cognitive domains (i.e., typical OCD appraisals) are introduced and explained to the patient. Together the patient and the therapist decide on which cognitive domains are central to the patient’s OCD. What follows are suggestions regarding how to cognitively challenge appraisals that are categorised in one of the domains discussed earlier. It should be noted that the cognitive challenge strategies represent the work of a number of investigators in the field including Freeston et al. (1996), van Oppen and Arntz (1994), Salkovskis and colleagues (e.g., Salkovskis & Kirk, 1997), and Whittal and McLean (1999). Challenging responsibility appraisals As has been suggested earlier, responsibility may be a central appraisal in OCD. If a responsibility appraisal is not immediately apparent, it can often be found during a downward arrow analysis. Occasionally a responsibility appraisal can be inferred from the emotion reported by the patient. Guilt and/or shame are strong clues that responsibility appraisals may be present. Freeston et al. (1996) suggested a courtroom procedure where an individual patient takes the roles of both the prosecuting and the defence attorneys. This strategy allows the patient to think critically about the reasoning behind their OCD beliefs as they are required to put forward “arguments” that are evidence-based and not emotion-based (i.e., emotional reasoning). An additional strategy that functions to challenge appraisals of inflated responsibility and has been described by a number of investigators is the piechart technique (e.g., van Oppen & Arntz, 1994). Figure 5.3 illustrates a pie-chart that was completed with a doubter/checker. In this example, an obsessional doubter was concerned with a basketball hoop he had put up for his son. The hoop had fallen over and caused a scrape on his son’s arm. Because the patient had put up the hoop, he blamed himself 100% for the accident. When completing a pie-chart the patient and therapist collaborate to determine all possible people or situational variables that may play a role in a particular event (e.g., a break-in). If the patient has responsibility appraisals, it is likely that he or she will automatically assume a large percentage, if not all, of the responsibility for the event. In dividing up the pie-chart, it is important to place other potential sources of responsibility in the pie first before placing the patient’s responsibility. Pie-charting with patients who have appraisals of inflated responsibility provides the tool for 138 Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean Playmate 5% Weather 10% Me 10% Toy makers 50% My son 20% Wife 5% Figure 5.3 The pie-chart technique. them to critically evaluate situations and hopefully establish more flexible guidelines to direct behaviour. A shorthand alternative to pie-charting that accomplishes the same goal is training patients to ask themselves the following question after they have assumed responsibility for an event or situation: “That’s one possibility (i.e., that I’m to blame), what are some others?” Challenging overimportance of thoughts Freeston et al. (1996) have provided an extensive discussion of challenging overimportance of thoughts. Attaching overimportance to one’s thoughts takes various forms: (1) my having the thought means it is important, (2) my having the thought increases the probability of the action, and (3) my having the thought and engaging in the action are morally equivalent. Collaboratively, the patient and therapist decide which of these three points are relevant. Examples of circular reasoning involved in appraising the thought as overimportant, and the process by which it developed, are discussed. Specifically, the natural reaction to appraising a thought as important is to dwell on the thought. Dwelling on the thought provides evidence that it is indeed important (i.e., why else would a person dwell on a thought unless it had some meaning and was important). Patients are asked to adopt a “come and go style” (i.e., non-dwelling) and test it in a behavioural experiment. On alternate days patients are asked to let intrusive thoughts “come and go” and on the other days to engage in their typical “fight and dwell” style. The outcome measure that patients are asked to record is the time spent engaging in obsessional thinking. Typically what patients report is a lower frequency, intensity, and duration of obsessions on the “come and go” days. Patients who have likelihood thought–action fusion appraisals often recall Psychosocial treatment for OCD 139 instances in which a thought was followed by the relevant event (e.g., thinking about an old friend and receiving a phone call from that person the same day) and overinterpret the significance of such events. These events can lead the person to believe that they have a special ability to predict the future. A strategy to normalise these “premonitions” is a survey conducted by the patient. Establish the patient’s predicted outcome for the survey and have them ask 10 friends if they experienced a situation similar to the example stated above. Freeston et al. (1996) also suggest conducting behavioural experiments to determine the power of thoughts (e.g., buy a lottery ticket and think about winning, attempt to kill a goldfish or break a reliable appliance by thinking about it). However, some patients may find these behavioural experiments too artificial (i.e., “because I purposely thought about it, the meaning is not the same”). In these cases patients should be required to keep a list of all naturally occurring episodes of likelihood TAF and the outcome (i.e., did the thought come true?). Frequently, due to selective attention, only those scenarios that support the hypothesis are remembered while those that provide evidence against it are forgotten. Keeping a running list of all likelihood TAFs and their outcomes can provide an accurate picture of the power of thoughts. Equating thoughts and action is particularly prevalent in people who have sexual, aggressive, or blasphemous intrusions. For example, a patient appraised his aggressive images that followed a mild confrontation as evidence “that somewhere deep down inside I have the ability to be like Hitler”. The continuum technique (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) may help challenge these appraisals. Draw a visual analogue scale with the anchors “best person ever” and “worst person ever” and ask patients to place people at these anchors and then place themselves on the continuum. Put a variety of other people on the continuum that reflect varying levels of “goodness” (e.g., a tax evader, someone who murders in self-defence, someone who cheats on their spouse, someone who has thoughts about cheating on their spouse but doesn’t do it, etc.). Subsequently, ask the patient to re-evaluate their own “goodness” (e.g., “because you have unwanted, unacceptable thoughts but never engaged in the action, does that make you as bad as someone who has purposely acted in a way to hurt another person?”). Freeston et al. (1996) have also suggested that thoughts can be disassociated from actions by establishing that morality is related to action and not thought. Define morality as using values and principles to guide behaviour. Thus morality is then equated to action and not thought. Challenging need to control thoughts The challenges associated with the need to control are similar to those associated with overimportance of thoughts and also may reflect appraisals of responsibility. Suppression (of the thought) is a common coping strategy for 140 Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean people who have these appraisals. The consequences of suppression are illustrated using the model and a behavioural experiment is devised such that patients are asked to alternate between suppressing the intrusive thoughts as they normally would and not fighting the thoughts. The dependent measure is the frequency, severity, and duration of intrusive thoughts. This behavioural experiment is very similar, if not identical, to alternating between “come and go” and “fight and dwell”. Challenging overestimation of threat The tendency to see danger or expect negative outcomes is readily apparent in OCD, but it is not as easily challenged compared to other anxiety disorders. For example, in panic disorder the feared consequences are typically imminent (e.g., “I’m about to have a heart attack”) and thus are open to disconfirmation. However, as noted by Salkovskis (1996) the feared consequences (and therefore the appraisals) of OCD patients are generally not open to disconfirmation because the threat is often future oriented (e.g., “I’ll go to hell because of my blasphemous thoughts”). Thus, challenges that focus on disconfirmation can be of limited usefulness. Occasionally, OCD patients report feared consequences that are associated with a finite, and therefore testable, time limit. For example, the contamination/washer who feared the onset of illness within one week following contact with a contaminate. In these situations, it is reasonable to attempt disconfirmation with a behavioural experiment or other cognitive challenges. Van Oppen and Arntz (1994) have discussed logical versus subjective probability estimation. Table 5.2 illustrates an example of the steps needed in calculating the logical probability. Table 5.2 An example of a cumulative odds ratio for a compulsive checker (initial chance of the house burning down was 20%) Step Chance Cumulative chance 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 1/10 1/10 1/10 1/100 1/100 1/10 1/100 1/1000 1/100 000 1/10 000 000 Not extinguish cigarette Spark falls on the floor Carpet catches on fire Carpet starts to burn and it is not noticed Patient notices the fire too late and can do nothing Subjective probability (20%) is compared to the logical probability (0.000 01%). For example, in the case of a checker who was concerned about causing a fire that would burn the house down, all steps required prior to the ultimate feared consequences are listed and the individual probabilities associated with each step are estimated. The probability of the final outcome (i.e., burning Psychosocial treatment for OCD 141 down the house) is the product of the previous steps (i.e., multiply previous steps with each other). This logical probability is compared to the subjective probability, the patient’s initial estimate prior to the cognitive challenge. Challenging intolerance for uncertainty Compared to people without OCD who assume a situation is safe until proven otherwise, Foa and Kozak (1986) have suggested that until disproven, people with OCD tend to assume that a situation is dangerous. Similarly, we have noticed that when some OCD people (e.g., doubters/checkers) cannot remember completing an action, they tend to assume it was not completed. Surveys can also be a useful tool to normalise and challenge certainty appraisals. Specifically, we have asked patients to survey non-OCD friends if they remembered locking their door when they last left their house. If they did not remember, patients ask how confident they are that the door is locked. If they did remember locking the door they are asked if it was due to an unusual occurrence (e.g., difficulty locking door). Typically, most non-OCD people cannot remember completing everyday, routine activities, thus hopefully normalising non-remembering. As with all surveys, patients should make a prediction about what they will expect to find and compare it to the results of their survey. However, caution must be used when assigning surveys Initial Appraisal My surroundings are not in order and it’s a reflection on me ⇓ If that were true, what would it mean to me? I’m embarrassed, feel guilty, unclean and not tidy ⇓ If that were true, what would it mean to me? I’m failing – not meeting standards set by others ⇓ If that were true, what would it mean to me? People would think I don’t care ⇓ If that were true, what would it mean to me? I’m not a good person ⇓ If that were true, what would it mean to me? Not worthy of living Figure 5.4 Downward arrow of a compulsive cleaner/organiser. 142 Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean such that they do not become a method for patients to seek reassurance rather than an information gathering exercise. As with all initial appraisals, it needs to be determined why uncertainty is particularly difficult. A downward arrow should be completed and may reveal underlying appraisals of threat overestimation and/or responsibility that if left unaddressed may result in less than satisfactory change. Challenging perfectionism Freeston et al. (1996) have discussed perfectionism in terms of need for certainty, need to know, and the need for control. In the patients we have worked with for whom perfection is a central concern the downward arrows typically reflect issues of self-worth. For example, Figure 5.4 illustrates a downward arrow of a compulsive cleaner/organiser who did not have contamination fears. In this case a continuum, as described earlier, was utilised. We also made a list of character traits of a good and bad person. It revealed the patient’s double standard; that she did not use cleanliness/neatness to judge other people’s self-worth but for herself it was the primary indication of her selfworth. This discovery was followed by a survey in which she asked friends/family to identify character traits associated with a good and a bad person. We also completed some behavioural experiments that entailed going outside with small stains on her clothes, leaving dishes in the sink when company was coming over, and altering the arrangement of knick knacks. These behavioural experiments were not done for the purpose of habituation as they are in ERP but rather to test the appraisal that cleanliness/neatness does not equal self-worth. After these behavioural experiments were completed the patient was debriefed regarding her experience and what she learned with respect to evidence for or against the alternative appraisal she discovered with the help of the therapist. Beliefs/assumptions underlying appraisals In addition to challenging appraisals, it is also important to address the beliefs/assumptions that are thought to result in appraisals. The beliefs/assumptions can be as varied as the appraisals they produce. For example, the assumptions of a checker we treated included “If I’m not perfect, I’m a failure”; “I can’t trust anybody but myself ”. “The world is dangerous” and “If I’m not careful something bad will happen” were some of the assumptions identified by a patient who felt compelled to imagine disasters happening to her family when she heard about such events in the news. If she did not “play out” these painful images she was convinced they would occur in real life. Once these assumptions are identified we have typically asked patients to Psychosocial treatment for OCD 143 describe the associated characteristics. Their adjectives have included rigid, unattainable, unrealistic, absolute, and threatening. Patients are asked if they can determine a connection between the assumptions and their OCD, the ways in which these rules have influenced their lives, and possible experiences that may have resulted in the formation of these rules. Most patients identify salient experiences that occurred early in their lives that logically relate to the rules. Alternatives to these rules are developed through cognitive challenging, which is similar to challenging appraisals. The goal is to develop alternatives that are flexible and reflect the complexities of adult life. As such, the alternatives that are developed are necessarily more elaborate (e.g., a possible alternative to “the world is dangerous” may be “there are certain dangerous things in our environment, but many are safe until demonstrated otherwise”). A special case of challenging beliefs is considered when working with patients who are primarily obsessional. The beliefs (and the appraisals) typically reflect some personal significance about the person. These people typically believe that the presence of the thoughts says something about their value as a human being. For example, we treated a female patient who had sexual obsessions and believed that she was a “totally depraved person”. Although they are generally considered to be more challenging to treat compared to people who have primary compulsions, obsessionals do benefit from CBT that focuses on changing the meaning of the intrusive thought (e.g., Freeston et al., 1996). Potential hazards for clinicians in using CBT with obsessive-compulsives Implementing CBT with obsessive-compulsives is complex and as such there are many places for clinicians who are unfamiliar with the protocol to have difficulty. Van Oppen and Arntz (1994) thoroughly discussed the pitfalls in doing CBT with OCD patients. Whittal and McLean (1999) have also discussed ways in which common problems are handled. One of the most common pitfalls is attempting to challenge the intrusion (e.g., “Is the stove off ?”) as opposed to the appraisal (e.g., “There will be a fire and it will be my fault”). Identifying appraisals can be difficult for patients to accomplish but intrusive thoughts are comparatively easy to identify. When patients are attempting to identify appraisals, they should focus on the personal meaning associated with the intrusive thought/image/impulse. Writing the cognitive behavioural model on a dry erase board or piece of paper and identifying the intrusion and appraisal from an example can also be helpful in differentiating the two concepts. If the intrusion is challenged and not the appraisal, it is likely that the clinician will be attempting to convince the patient that their intrusion is not true. Most patients already know it is not true and this strategy will at best not be helpful and at worst result in an argument. 144 Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean Identifying feared consequences and labelling them as appraisals is another common problem. For example, with the intrusion “is the stove off ”, we have had patients initially identify the appraisal as “the house will catch on fire”, which is the feared consequence. To accurately identify the appraisal, the meaning behind the feared consequence must be identified (i.e., “what would it mean to you if the house caught on fire?”). Of the cognitive domains discussed earlier, clinicians who are unfamiliar with contemporary CBT with OCD patients may tend to rely too much on overestimation of threat and focus on reducing probability. Overestimation of danger is common among the anxiety disorders and calculating logical probabilities is a central feature of panic treatment (e.g., Otto, Pollack, & Barlow, 1996) and is a powerful strategy. Treatment of OCD is more complex compared to panic. Although a reduction of probability (as illustrated in Table 5.2) is part of cognitive challenging, it is not sufficient. As indicated by van Oppen and Arntz (1994), risk = chance × consequence. Risk will not be reduced without attending to consequence (which is typically responsibility related) in addition to probability. Similarly, clinicians who were trained as behaviourists or those who are accustomed to doing ERP with OCD patients may rely too heavily upon behavioural experiments to change appraisal. Contemporary CBT with OCD patients is much more than doing behavioural experiments to “see what happens”. Treatment outcome using CBT To date there have only been two published controlled trials using the contemporary CBT protocol (Freeston, Ladouceur, Gagnon, Thibodeau, Rheume, Letarte, & Bujold, 1997; van Oppen, de Haan, van Balkom, Spinhoven, Hoogduin, & van Dyck, 1995) and a handful of case studies (e.g., Ladouceur, Freeston, Gagnon, Thibodeau, & Dumont, 1995; Ladouceur, Leger, Rheume, & Dube, 1996). Emmelkamp and colleagues (e.g., Emmelkamp & Beens, 1991; Emmelkamp, Visser, & Hoekstra, 1988) have presented treatment outcome data using an early version of the CBT that is now being advocated. Freeston et al. (1997) used a contemporary CBT package to treat 29 OCD patients who exclusively experienced covert compulsions. Treatment involved a cognitive behavioural explanation of the occurrence and maintenance of obsessive thoughts, exposure to obsessive thoughts, preventing all neutralising, cognitive challenging of appraisals, and relapse prevention. Compared to a wait-list condition, the treated group reported a significant decrease in obsessions and anxiety and an increase in functioning. These gains were maintained at 6-month follow-up. Although ERP was used in this study, Freeston et al. (1997) suggest that the cognitive restructuring techniques were essential to the successful outcome given that obsessional ruminators are notoriously difficult to treat behaviourally. Psychosocial treatment for OCD 145 Van Oppen et al. (1995) reported on 57 patients who were treated with either cognitive therapy as conceptualised by Salkovskis (1985) or exposure. Patients in the cognitive therapy group completed behavioural experiments to test appraisals and thus did receive some exposure. There were no statistical differences on OCD severity between the groups at post-treatment. However, a higher percentage of patients in the cognitive therapy group were rated recovered (50%) compared to the exposure group (28%). As noted by Steketee, Frost, Rheume and Wilhelm (1998), the post-treatment dependent measure (Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale – YBOCS; Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Mazure, Fleishmann, Hill, Heninger, & Charney, 1989) was higher compared to studies that used similar protocols, which suggests that the exposure was not as powerful as in previous studies. A treatment trial has recently been completed at the University of British Columbia comparing the CBT package described in this chapter and ERP (Whittal, McLean, Thordarson, Koch, Taylor, & Sochting, 1998). Patients were treated in small groups with two therapists; 31 patients completed the CBT condition and 32 completed the ERP condition. Patients in both conditions reported a significant decrease in YBOCS score pre to post treatment. However, at post-treatment YBOCS scores of patients in the ERP condition (13.2) were significantly lower compared to patients in the CBT condition (16.1). It is possible that the nature of group treatment did not allow for the idiosyncratic OCD appraisals to be properly addressed, thereby making treatment less effective. To address this issue, the same protocol was used to treat patients individually. Data collection is currently ongoing. At the time of writing this chapter 14 patients have completed the CBT condition and 23 have completed the ERP condition. Although the sample size is relatively small, YBOCS scores are lower for subjects in the CBT condition (7.9) compared to the ERP condition (10.1). Although the results of the individual study are tentative, it appears that ERP works equally well in groups or individually, whereas CBT is more effective individually than in groups. Case studies or case series have also pointed to the effectiveness of a cognitively focused OCD treatment. For example, Ladouceur et al. (1995) completed CBT on three patients who experienced obsessions and covert compulsions. Subjects were treated in a multiple baseline design where treatment was initiated on different days for each of the three patients. Treatment involved a combination of exposure and response prevention using a “loop tape” and cognitive restructuring that focused on inflated responsibility, perfectionism, overimportance of thoughts, and overestimations of danger. All patients responded positively to the cognitive behavioural intervention and maintained their gains at follow-up. Ladouceur et al. (1995) indicated that it was impossible to determine if the behavioural elements or the cognitive components or the combination were responsible for the successful outcomes. Exposure may function to provide evidence that the original OCD appraisals are not valid (i.e., that the situation is not as dangerous as was originally 146 Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean appraised). To determine the utility of a cognitive treatment approach, it would need to be tested in the absence of exposure. Ladouceur et al. (1996) treated four checkers with a purely cognitive protocol that focused on appraisals of inflated responsibility. These patients were given no exposure homework during the course of treatment. Ladouceur et al. (1996) reported a significant decrease in pre- to postYBOCS scores for all participants. Gains were maintained at 6- and 12-month follow-ups for three of the four patients. Conclusions Exposure and response prevention has been the psychosocial treatment of choice for OCD, resulting in well-documented and consistent therapeutic outcomes. However, fear generated by the rigours of exposure-based treatment has resulted in relatively high levels of treatment refusal and drop-outs, and obsessions without overt rituals have proven difficult to engage with ERP. Such limitations have encouraged exploration of alternative models of OCD. Following Salkovskis’ (1985) influential cognitive theory of OCD in which it was proposed that beliefs about personal responsibility form threatening appraisals of intrusive thoughts in OCD sufferers, the work of a number of investigators systematically articulated other distorted beliefs and implicated their role in OCD. In the CBT protocol for OCD outlined in this chapter, five types of distorted beliefs, identified by consensus amongst investigators, are defined and illustrated. It is expected that the structure and function of such beliefs will be further clarified over time. We have outlined a CBT protocol for OCD that addresses some of the intricacies of this treatment as well as typical difficulties faced by therapists and have suggested ways around the challenges. Early CBT case studies and controlled trials have been promising, posting results generally equivalent to ERP and in several studies superior. The mechanisms by which ERP and CBT effect change are probably more complex than habituation and insight, respectively. Patients undergoing ERP may well be doing self-directed cognitive therapy, unbeknownst to the therapist, as a function of interpreting their exposure-based experiences. And it appears that CBT induced improvements are the result of much more than insight and depend upon a skilled and systematic consideration of alternative explanations to invalidate fearful appraisals of intrusive thoughts and images. CBT is well received by OCD patients and holds considerable hope for those who cannot tolerate, or who are unresponsive to, ERP. Interestingly, treatment effectiveness may be a question of individual differences in matching patients to type and modality of treatment. More concrete and less psychologically minded OCD patients may do better with ERP, while others benefit more from CBT. Our preliminary evidence is that ERP is easier to deliver in group format than CBT, but is less effective than CBT when delivered on an individual basis. Psychosocial treatment for OCD 147 References Abramowitz, J.S. (1996). Variants of exposure and response prevention in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy, 27, 583–600. Antony, M.M., Purdon, C.L., Huta, V., & Swinson, R.P. (1998). Dimensions of perfectionism across the anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 1143–1154. Beck, A.T., Rush. J.A., Shaw, B.F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford. Carr, A.T. (1974). Compulsive neurosis: A review of the literature. Psychological Bulletin, 81, 311–318. Clark, D.A. & Purdon, C. (1993). New perspectives for a cognitive theory of obsessions. Australian Psychologist, 28, 161–167. Cox, B.J., Fergus, K.D., & Swinson, R.P. (1994). Patient satisfaction with behavioral treatments for panic disorder with agoraphobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 8, 193–206. Emmelkamp, P.M.G. & Beens, H. (1991). Cognitive therapy with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparative evaluation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 29, 293–300. Emmelkamp, P.M.G., Viser, S., & Hoekstra, R.J. (1988). Cognitive therapy vs exposure in vivo in the treatment of obsessive-compulsives. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 12, 103–114. Foa, E.B. & Franklin, M.E. (1998). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. In D.K. Routh & R.J. DeRubeis (Eds.), The Science of Clinical Psychology (pp. 235–264). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Foa, E.B., & Kozak, M.J. (1986). Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 20–35. Foa, E.B., & Kozak, M.J. (1996). Psychological treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. In M.R. Mavissakalian & R.F. Prien (Eds.), Long-term Treatment of Anxiety Disorders (pp. 285–309). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press. Foa, E.B., Franklin, M.E., & Kozak, M.J. (1998). Psychosocial treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Literature review. In R.P. Swinson, M.M. Antony, S. Rachman & M.A. Richter (Eds.), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Theory, Research, & Treatment (pp. 258–276). New York: Guilford Press. Foa, E.B., Steketee, G., & Ozarow, B.J. (1985). Behavior therapy with obsessivecompulsives: From theory to treatment. In M. Mavissakalian, S.M. Turner & L. Michelson (Eds.), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Psychological and Pharmacological treatments (pp. 49–120). New York: Plenum Press. Freeston, M.H., Ladouceur, R., Gagnon, F., Thibodeau, N., Rheume, J., Letarte, H., & Bujold, A. (1997). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of obsessive thoughts: A controlled study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 405–413. Freeston, M.H., Rheume, J., & Ladouceur, R. (1996). Correcting faulty appraisals of obsessional thoughts. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 433–446. Goodman, W.K., Price, L.H., Rasmussen, S.A., Mazure, C., Fleishmann, R.L., Hill, C.L., Heninger, G.R., & Charney, D.S. (1989). The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46, 1006–1011. 148 Maureen L. Whittal, S. Rachman, and Peter D. McLean Hewitt, P.L. & Flett, G.L. (1991). Dimensions of perfectionism in unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 98–101. Hewitt, P.L. & Flett, G.L. (1993). Dimensions of perfectionism, daily stress, and depression: A test of the specific vulnerability hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 58–65. Ladouceur, R., Freeston, M.H., Gagnon, F., Thibodeau, N., & Dumont, J. (1995). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of obsessions. Behavior Modification, 19, 247–257. Ladouceur, R., Leger, E., Rheume, J., & Dube, D. (1996). Correction of inflated responsibility in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 767–774. McFall, M.E. & Wollersheim, J.P. (1979). Obsessive-compulsive neurosis: A cognitivebehavioral formulation and approach to treatment. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 3, 333–348. Meyer, V. (1966). Modification of expectations in cases with obsessional rituals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 4, 273–280. Obsessive-Compulsive Cognitions Working Group (1997). Cognitive assessment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 667–682. O’Sullivan, G. & Marks, I. (1991). Follow-up studies of behavioral treatment of phobic and obsessive compulsive neuroses. Psychiatric Annals, 21, 368–373. Otto, M.W., Pollack, M.H., & Barlow, D.H. (1996). Stopping Anxiety Medication. New York: Greywind. Pigott, T.A. & Seay, S. (1998). Biological treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Literature review. In R.P. Swinson, M.M. Antony, S. Rachman, & M.A. Richter (Eds.), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Theory, Research, & Treatment (pp. 298–326). New York: Guilford Press. Purdon, C. (1999). Thought suppression in psychopathology. Behaviour Research and Therapy. Rachman, S. (1983). Obstacles to the successful treatment of obsessions. In E. Foa & P.M.G. Emmelkamp (Eds.), Failures in Behavior Therapy (pp. 35–57). New York: John Wiley & Sons. Rachman, S., & Hodgson, R. (1980). Obsessions and Compulsions. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Rachman, S., & de Silva, P. (1978). Abnormal and normal obsessions. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 16, 233–248. Rachman, S. & Shafran, R. (1997). Cognitive and behavioral features in obsessivecompulsive disorder. In R.P. Swinson, M.M. Antony, S. Rachman, & M.A. Richter (Eds.), Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Theory, research, & treatment (pp. 51–78). New York: Guildford Press. Salkovskis, P.M. (1985). Obsessional-compulsive problems: A cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 23, 571–583. Salkovskis, P.M. (1991). The importance of behaviour in the maintenance of anxiety a panic: A cognitive account. Behavioural psychotherapy, 19, 6–19. Salkovskis, P.M. (1996). Cognitive-behavioural approaches to the understanding of obsessional problems. In R. Rapee (Ed.), Current Controversies in the Anxiety Disorders (103–133). New York: Guilford. Salkovskis, P.M. & Harrison, J. (1984). Abnormal and normal obsessions: A replication. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 22, 549–552. Salkovskis, P.M. & Kirk, J. (1997). Obsessive-compulsive disorder. In D.M. Clark & Psychosocial treatment for OCD 149 C.G. Fairburn (Eds.), Science and Practice of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (pp. 179–208). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Salkovskis, P.M. & Wesbrook, D. (1989). Behaviour therapy and obsessional rumination: Can failure be turned into success? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 27, 149–160. Shafran, R., Thordarson, D.S., & Rachman, S. (1996). Thought action fusion in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 10, 379–391. Srinivasagam, N.M., Daye, W.H., Plotnicov, K.H., Greeno, C., Weltzin, T.E., & Rao, R. (1995). Persistent perfectionism, symmetry, and exactness after long-term recovery from anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 1630–1634. Stanley, M.A. & Turner, S.M. (1995). Current status of pharmacological and behavioral treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behavior Therapy, 26, 163–186. Steketee, G.S., Frost, R.O., Rheume, J., & Wilhelm, S. (1998). Cognitive theory and treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. In M.A. Jenike, L. Baer, & W.E. Minichiello (Eds.), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders: Practical Management (3rd edition). New York: Mosby. Van Oppen, P. & Arntz, A. (1994). Cognitive therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 32, 79–87. Van Oppen, P., de Haan, E., van Balkom, A.J.L.M., Spinhoven, P., Hoogduin, K., & van Dyck, R. (1995). Cognitive therapy and exposure in vivo in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 379–390. Wegner, D. (1989). White Bears and Other Unwanted Thoughts. New York: Viking/Penguin. Whittal, M.L. & McLean, P.D. (1999). CBT for OCD: The rationale, protocol, and challenges. Cognitive and behavioral practice, 6, 383–396. Whittal, M.L. McLean, P.D., Thordarson, D.S., Koch, W.J., Paterson, R. Taylor, S., & Sochting, I. (1998). OCD treatment outcome: Behavioral and cognitive behavioral techniques. Paper presented at the meetings for the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Washington, DC. Chapter 6 Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and generalised anxiety disorder Michelle G. Newman and Thomas D. Borkovec The goal of this chapter is to present an overview of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). The symptomatic picture of GAD is first described. Specific techniques developed by cognitive behaviour therapists to reduce GAD symptoms are then presented. In addition, the empirical evidence supporting the effectiveness of CBT for GAD is reviewed. Although CBT is the only current form of therapy for GAD that has been empirically supported (Chambless, Sanderson, Shoham, Johnson, Pope, Crits-Christoph et al., 1996), this chapter also addresses the limitations of this treatment and suggests research directions for improving its effectiveness. Symptomatology According to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), the current definition for GAD is excessive and uncontrollable worry about a number of events or activities. To be diagnosed, the person has to worry more days than not for at least 6 months and the worry must be associated with significant distress or impaired functioning. In addition, the person’s symptoms cannot be due to a drug, a general medical condition, or another Axis I condition. Throughout most of the time period the person is uncontrollably worrying, he or she must also be experiencing three of six symptoms (restless/keyed-up/on-edge, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance) that are associated with autonomic nervous system activity. The selection of these particular symptoms was based on psychophysiological research showing reduced variability in autonomic nervous system activity of GAD clients (e.g., Hoehn-Saric, McLeod, & Zimmerli, 1989). Prior to DSM-IV, the diagnostic criteria for GAD went through several changes. It first appeared in 1980 in the third edition of the DSM (American Psychiatric Association, 1980) as a subdivision of the previous category of anxiety neurosis. At this time, the diagnostic criteria focused on chronic Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and GAD 151 diffuse anxiety, symptoms of apprehensive expectation (worry), vigilance or scanning, motor tension, and autonomic hyperactivity. However, GAD was not diagnosed if the individual also met criteria for any other Axis I condition. When DSM-III was revised to DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987), GAD was made a primary diagnosis even if the person met criteria for other Axis I disorders. Another change was that its central component was considered to be apprehensive expectation (worry). For diagnosis to occur, the person also had to experience six of eighteen symptoms associated with motor tension, autonomic hyperactivity, and vigilance (e.g., restlessness, frequent urination, and exaggerated startle response). Although the diagnosis of GAD has only been recognised recently, research evidence suggests that a significant number of individuals suffer from this disorder, with prevalence rates of 3.6 to 5.1% for lifetime and 3.1% for one year (Kendler, Neale, Kessler, Heath, & Eaves, 1992; Wittchen, Zhao, Kessler, & Eaton, 1994). GAD is also one of the most frequent additional diagnoses to other anxiety and mood disorders (Brown & Barlow, 1992). In addition to being a frequent primary or secondary disorder, the central feature of GAD, excessive or uncontrollable worry, is a common symptom in all of the anxiety and mood disorders (Barlow, 1988). Moreover, when GAD is successfully treated, comorbid diagnoses are diminished or eliminated (Borkovec, Abel, and Newman, 1995). In fact, its early onset, chronicity, and resistance to change has led researchers to suggest that GAD forms the basis of other anxiety disorders (Brown, Barlow, & Liebowitz, 1994). Moreover, GAD may play a role in the maintenance of many disorders. Research suggests that worry prevents emotional processing. Worry may thus interfere with the treatment of psychological problems, such as anxiety disorders, for which such processing is crucial for therapeutic change (Borkovec, 1994; Borkovec & Newman, 1998; Newman, 2000b). The development of effective therapies for GAD may therefore lead to advances in the treatment or prevention of other disorders. Cognitive behavioural therapy techniques The symptoms of GAD are thought to result from spiralling, habitual, inflexible interactions of cognitive, imaginal, and physiological responses to constantly perceived threat (Barlow, 1988; Borkovec & Inz, 1990). Cognitive behavioural therapists have developed a series of techniques meant to target each of the cognitive, imaginal, and physiological response systems (Newman, 2000a; Newman & Borkovec, 1995). These interventions are aimed at providing the client with numerous coping skills, with the goal that it might help them develop a flexible, adaptive lifestyle conducive to reduced anxious experience. The specific techniques that are part of the clinical repertoire of CBT therapists include self-monitoring, stimulus control, relaxation, selfcontrol desensitisation, and cognitive therapy. This section will provide a 152 Michelle G. Newman and Thomas D. Borkovec detailed description of each of these techniques. Before doing so, however, it is important to present a brief description of the overarching rationale and guidelines underlying this treatment. Cognitive behavioural therapy is based on the premise that most of the therapeutic change takes place between sessions and is the consequence of client practice and application of CBT techniques. Therefore, the therapist must ensure that clients fully understand the value and method of application of each technique as well as the importance of regular practice. In therapy for GAD, clients are told that worry is the result of habits from the past and that therapy is focused on teaching them new skills. As with any skill, therapy techniques require frequent practice before they can be mastered. Each time a new cognitive or behavioural technique is introduced in therapy, it is helpful for the therapist to practise it with the client in an attempt to create an immediate, noticeable, and positive effect, however slight. Such a demonstration may help clients develop confidence that the technique can make a difference for them with further practice and application. The more confidence clients have in any one technique, the more motivated they will be to practise it routinely and the more helpful it will be. Self-monitoring and early cue detection The first step in therapy is the detection of cues that trigger anxiety. These cues can be either internal or external. Important internal cues may include attention, thoughts, images, bodily sensations (especially muscle tension), emotions, and behaviours. External cues refer to stressful events in a client’s life. These can include such things as a subtle comment or gesture made by another person or unexpected financial or work demands, as well as ambiguous situations in which the client lacks information. In CBT, more attention is placed on internal cues than external cues. Clients are told that it is not their reactions to events that are the problem. Their reactions to their reactions are the problem. The goal of therapy is to change their reactions to their reactions and to strengthen new coping responses. Therapy emphasises detection of initial cues of anxiety. These early cues typically lead to a spiralling up of anxiety involving, for example, the perception of stressful events (e.g., an ambiguous comment made by their boss) followed by an anxious thought (“he thinks I’m not doing a good job”), which leads to a physiological response (e.g., increased muscular tension), which in turn creates another worrisome thought (“maybe he will fire me”), leading to a negative emotion (e.g., anxiety and depression), which then generates more anxious thoughts (e.g., “I’m a failure and I will never be able to provide for my family”). By intervening in response to early cues for anxiety, therapists teach clients how to cut off the anxiety spiral before it reaches a high level of intensity. The earlier clients can identify initial cues for anxiety, the earlier they can intervene. Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and GAD 153 There are many approaches that can be used by therapists to help clients identify early anxiety cues. One of them is to ask clients to give a detailed description of a situation that created worry in terms of what they attended to, did, thought, imagined, and physically and emotionally felt. Alternatively, the therapist can ask them to imagine themselves in a past or upcoming anxiety-provoking situation. Another method is to have clients recreate their worry process by worrying silently about a topic of concern. Clients may also worry out loud to provide the therapist with information on the nature and content of their worry. Moreover, the therapist can help clients identify early cues by looking for any detectable shift in their affective state and asking them to describe what is occurring at that moment. In addition, clients can be encouraged to tell the therapist when they notice the beginning of anxiety cues. It is also helpful to have clients regularly record information about worry periods as they are happening. Clients can document the first external or internal cue that they noticed, the content of the worry, their highest level of anxiety, and the length of time that they worried. This method can help them gather an accurate record. Self-monitoring of anxiety cues on a moment-to-moment basis forms the foundation for CBT with GAD. In addition to aiding the identification of anxiety triggers, such self-monitoring helps the therapist identify particular patterns that are idiosyncratic to any one client and to track the impact of therapy. Moreover, clients can use self-monitoring to identify and attend to additional emotions other than anxiety such as anger, frustration, and depression. Such emotions are frequently involved as an initial cue or integral part of an anxiety spiral and could therefore be specific targets for CBT intervention. Remembering to record information at the time it happens is a difficult challenge for clients. However, the therapist can help the client by suggesting ways to create reminders in their environment. For example, the client can monitor their anxiety every hour or at every change in activity. Over time, the client can begin to identify more specific reminder cues that are stressful to them, such as whenever the phone rings, or whenever a particular co-worker is seen during the day. The important thing is to establish an ample number of effective cues so that clients are repeatedly reminded to observe their inner processes. The ultimate goal is to develop a habit of recognising early anxiety and to intervene at that moment with all the coping responses that have been learned up to that point. Stimulus control methods GAD clients develop the habit of worrying in multiple situations. Such a habit creates numerous internal and external cues that over time come to trigger worry responses in and of themselves. Stimulus control techniques can help the client reduce the association between worry and these specific cues 154 Michelle G. Newman and Thomas D. Borkovec (i.e., the discriminative stimuli), which in turn can reduce the intensity and frequency of the worry response. As a first step, clients are instructed to schedule a daily 30-minute period during which they will worry. This period should occur at the same time and place every day and may not be associated with work or relaxation. At all other times and places, they must actively postpone any worrying until this 30-minute period. To achieve this task clients must pay attention to the internal and external events that start the spiral cycle of worrisome thoughts and anxiety responses (e.g., walking into their office and sitting down in front of the computer as they prepare to write a paper). Whenever they detect such a cue they can postpone their worry (“Okay, I know that I usually get very anxious when I start writing a paper, but this time I will postpone my worry until my designated worry period. At that time, I can worry as much as I want”) and concentrate on the task that they had planned to do (e.g., writing for an hour) or focus their attention on what is going on in their environment (i.e., to focus on steps necessary to write, but this time without worrying). When the worry period arrives, the client can go to the designated place and worry intensively. If, for any reason, they have difficulty controlling or postponing their worry during specific times of the day (e.g., while lying in bed at night prior to going to sleep), they should go immediately to the designated “worry” spot, and worry intensively until their worry is under control. Only then are they allowed to go back to their previous destination. These procedures provide the client with a sense of control over their worry. With practice, they learn that they can intentionally reduce their worry in specific situations, as well as increase it when they decide to do so. As the therapy progresses, therapists also use the client’s ability to create worry on demand to help them practise cognitive behavioural techniques to reduce the worry response. The effectiveness of these stimulus control methods has been supported with college samples of chronic worriers (Borkovec, Wilkinson, Folensbee, & Lerman, 1983). Relaxation methods The physiological process of GAD clients is characterised by autonomic rigidity. Methods that can increase autonomic flexibility may therefore be beneficial to individuals with GAD. In the clinical repertoire of CBT are a number of relaxation methods that are designed to increase such flexibility. Therapists, for example, may use diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, pleasant imagery, meditation, and daily application of applied relaxation. The variety of these techniques allows the therapist to identify which methods are most effective for specific individuals who are experiencing anxiety in particular situations. Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and GAD 155 Diaphragmatic breathing and progressive muscle relaxation A relaxation technique that is easy to teach clients and that often produces a rapid relaxation response is slowed, paced, diaphragmatic breathing. This technique can be introduced by telling clients that people with anxiety problems often breathe more from their chest than their diaphragm. Chest breathing stimulates the sympathetic autonomic nervous system which produces many uncomfortable bodily sensations that people experience when they are anxious. On the other hand, diaphragmatic breathing stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system which produces the comfortable feelings experienced during deeply relaxed states. To demonstrate the anxiety-inducing impact of chest breathing, the therapist can first model and then have clients practise rapid, shallow, thoracic breathing for 1 minute or until they begin to feel anxious or uncomfortable. This can be followed by slowed paced diaphragm breathing to reduce their anxiety. To help clients ensure that they are breathing from their diaphragm, they can place one hand on their diaphragm below their belly button and the other hand on their chest. As they breathe, only the hand on their diaphragm should move. They should also be told to keep their breathing smooth by inhaling and exhaling an even amount of air. These exercises help clients understand the impact their breathing has on how they feel as well as their ability to instantly control their physiological and psychological response. Clients are encouraged to shift to diaphragmatic breathing whenever they notice chest breathing during the session, or in their day-to-day activities. Monitoring and modifying their breathing habits provide clients with a fastacting and easy-to-learn method to control anxiety spirals upon early cue detection. Similar to other cognitive behavioural techniques, the key for the effectiveness of diaphragmatic breathing is repeated rehearsal. Another helpful relaxation technique is progressive muscle relaxation (PMR), which involves systematic tension production and subsequent release of various muscle groups. Initially, clients tense and release 16 separate muscle groups. The muscle groups that are addressed include the right hand and lower arm, left hand and lower arm, right biceps, left biceps, upper face, central face, lower face, neck, chest, shoulders and upper back, abdomen, right thigh, left thigh, right calf, left calf, right foot and left foot. As therapy progresses, muscle groups are tensed and relaxed in combinations. Thus, after 16 muscle group PMR is mastered, the client can produce and release tension in 7 combined muscle groups and then 4 muscle groups each tensed at the same time (e.g., muscles of the left and right arms, hand and biceps, muscles of the face and neck, muscles of the chest, shoulders, upper back and abdomen, and muscles of the left and right thigh, calf and foot). Eventually, clients learn to relax their muscle groups without tensing them; the muscles are relaxed by the client remembering the feeling created by repeated exercise of tension and release. This is caledl “relaxation-by-recall”. 156 Michelle G. Newman and Thomas D. Borkovec At the same time clients are taught PMR, they are introduced to the notion of “letting go” of anxiety. Specifically, the client is taught that during relaxation practice, as they are letting go of physical tension, they can actively let go of anxious emotions. The process of letting go can also be generalised to other components of the anxiety response. Clients, for example, can stop their anxiety spiral by letting go of worrisome thoughts or images. To help clients master the skill of letting go, the therapist can tell them to focus on their breathing during PMR and to clear their minds of all other thoughts. Whenever they become aware of a distracting thought, image, or emotion, they should not force it away, but rather, imagine it floating out of their head as though it were a balloon filled with helium. Another helpful technique is to have clients repeat a particular cue word such as the word “calm” over and over, similar to a mantra during meditation practice. As they are practising PMR, their goal is to focus all of their attention on that particular cue word. Whenever they notice their mind wandering, they can use that word to refocus their attention. Frequently, diaphragmatic breathing and PMR are not sufficient to allow GAD clients to achieve a pleasant state of relaxation. This is because the subjective world of these individuals is dominated by worrisome images and thoughts. Cognitive behaviour therapists therefore often use relaxation techniques which focus on positive mental images. In using pleasant imagery, for example, therapists invite the client to imagine a person or a place in their life that is associated with a feeling of serenity, peace, and/or comfort. Whenever they are feeling anxious, the client can then imagine themselves in that place with all of the sights, sounds, smells, and tactile sensations that would be present. A client, for example, may imagine him/herself sailing on a calm sea, enjoying a cool breeze, a warm sun, and the thought of an infinite and serene journey. The therapist can also apply the technique of guided pleasant imagery in which the therapist and client work together to construct a relaxing mental scene for the client to imagine and then elaborate on as the client progressively achieves a deeper state of relaxation. Using the above example, the client might first imagine setting off on a sailboat in the calm sea and as the ship moves away from the harbour, they are leaving behind all their troubles, and becoming more and more relaxed as the people, houses, and boats on the shore get smaller and smaller. Therapists should be aware, however, that for some GAD clients letting go of tension to attain a fully relaxed state may, in itself, generate anxiety which can interfere with that very goal. This is because many GAD clients are perfectionistic, fear losing control, or are uncomfortable with the increased awareness of feelings sometimes elicited by relaxation (Heide & Borkovec, 1984). If the means for reducing anxiety is itself anxiety-provoking, the probability of a therapeutic impact is minimal. In fact, in the three published GAD therapy investigations that assessed for relaxation-induced anxiety (RIA) during training, it negatively predicted outcome (Borkovec & Costello, Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and GAD 157 1993; Borkovec & Mathews, 1988; Borkovec, Mathews, Chambers, Ebrahimi, Lytle, & Nelson, 1987). Luckily, there are several techniques available that can help the therapist work around this problem. In one of these techniques, the therapist can describe relaxation training in terms of “movement toward relaxation”. The client can be told that the goal of the treatment is not to achieve a specific end point where the presence of anxiety has been eradicated from their life. The essence of the treatment is presented as a gradual process of change which is aimed at facilitating clients’ mastery over the anxiety spiral pattern that has invaded their life. Another way to reduce the likelihood that clients will experience RIA is to emphasise repeated applications of brief relaxation responses to detected anxiety cues in place of twice-a-day formal practice of deep relaxation. Clients can be told that frequency of application is more important than depth of relaxation. Teaching clients alternative relaxation techniques is also helpful because clients who experience RIA in response to one relaxation technique rarely experience it in response to another (Heide & Borkovec, 1983). Moreover, in more difficult cases, RIA can be viewed as comparable to graduated exposure to a feared situation. Similar to other such exposure methods, relaxation can be practised by having the client expose themselves to increasingly deeper relaxation levels as therapy progresses. When these techniques were used in a recently completed Penn State therapy study (Borkevec, Newman, Pincus, & Lytle, in press), the initial presence of RIA no longer predicted treatment outcome. An important underlying objective of relaxation training is to decrease the amount of time clients spend worrying about the future or the past by increasing their focus on the present moment. Focusing excessively on the future or past is an inattention to the immediate environment. This inattention impedes clients’ ability to process new information which prevents learning and development. The clients can, however, learn to re-focus their attention on the present environment. They can begin by closing their eyes and getting in touch with whatever small sensations they may hear, smell, and feel. Then, whenever they notice their mind wandering, they can re-focus their attention on these sensations. After doing this exercise with their eyes closed, clients can repeat it with their eyes open and eventually as they are walking around. After they have practised this exercise with the therapist, clients can also try this exercise as a homework assignment whenever they notice that they are not focused on the present moment. Another goal of relaxation is to increase the clients’ adaptive behaviour. Since anxiety has been repeatedly shown to reduce performance, it is not surprising that with increased mastery of relaxation techniques clients report being more effective at work and more at ease in social situations. Because all aspects of the human system are in constant interaction, the decrease in autonomic rigidity created by apparently simple relaxation techniques can have a synergetic impact on other components of the clients’ functioning. The 158 Michelle G. Newman and Thomas D. Borkovec therapeutic benefit of relaxation practice, however, is more than likely to increase with the addition of applied relaxation. Applied relaxation (AR) Applied relaxation is a technique in which clients actively let go of tension on a moment-to-moment basis whenever they detect initial anxiety cues or subtle shifts toward anxiety. Clients can be asked to regularly scan their body and mind for physiological, cognitive, or behavioural anxiety cues, and then to use diaphragmatic breathing or release of muscular tension as a rapid coping response to such cues. As opposed to the relaxation techniques described above, AR is not used by the client at times when they are alone and in a comfortable situation (e.g., lying in bed while getting ready to read a novel). It is primarily designed to help clients reduce their anxiety as they are engaged in day-to-day activities, such as performing a task at work or interacting with others. A specific aspect of this technique is called cue-controlled applied relaxation. In cue-controlled relaxation, a particular word (e.g., “relax”, “calm”, or a word taken from meditational focusing devices) that was paired with the feeling of “letting go” during the formal practice of any relaxation technique is used by clients as a signal for applied relaxation in the midst of stressful situations (internal or external) or in response to any anxiety trigger. To facilitate the generalisation of applied relaxation skills to daily living, clients can practise differential relaxation training. For this technique, clients are taught to relax themselves when walking and as they engage in various common activities. The therapist helps clients to differentiate the muscular tension that is required for specific activities from any excessive or unnecessary tension that clients typically experience when performing these activities. The client’s task is then to learn how to relax away such excessive tension, without removing themselves from the activity in which they are engaged. Similar to other CBT techniques, AR should be used frequently between sessions to help clients adopt a more habitually relaxed lifestyle. They can be told that stressful events have three phases (anticipation of the event, during the event, and recovery from the event) and that applied relaxation is particularly helpful when used throughout each of these phases. Using AR in anticipation of or during the event may well prevent the spiral of anxiety from reaching a paralysing level. The same coping skills used after the event can help clients more rapidly achieve a sense of self-control and decrease the amount of time they may spend worrying about the past event. As they develop increased mastery of AR, clients can apply this technique to progressively more stressful situations, as would be done in any type of exposure intervention. Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and GAD 159 Self-control desensitisation (SCD) Clients’ physiological reactions to images are similar to their reactions to real events. In addition, worrying prevents emotional processing, whereas imagery can be an effective method for engaging such processing. For these reasons, imagery exposure is particularly important to the treatment of GAD. Self-control desensitisation (SCD) is an imagery technique that was designed to be applied to anxiety problems such as GAD, in which there are no discrete phobic stimuli (Goldfried, 1971). This technique requires less detailed hierarchy construction than techniques associated with circumscribed anxiety problems (e.g., systematic desensitisation for insect phobia). Instead of identifying a phobic stimulus, clients identify external situations that are representative of those associated with anxiety and worry. Within each situation, the client also identifies physiological, cognitive (especially worry and catastrophic images), and behavioural cues for their anxiety spirals as well as external triggers. Identified situations are roughly graded as mild, moderate, or severe in anxiety-provoking value. The client can begin with mildly anxiety-provoking situations, and as they become more proficient with the technique they can move to situations rated as moderate and later severe. The implementation of SCD requires several steps. In the first step, clients formally practise PMR until they are fully relaxed. Next, they imagine themselves in a circumstance that commonly elicits anxiety. For example, a client who often worries about being late, might imagine themselves in their house, about to leave for work, and unable to find their car keys. They continue to imagine themselves in this scene until they notice anxiety cues. As soon as anxiety is elicited (which can be signalled to the therapist during in-session practice by raising their finger), they relax it away as they picture themselves coping effectively with the situation (e.g., calmly trying to recall the last place they may have left their car keys). After they no longer notice the anxiety cues (which can be signalled by lowering their finger), they continue to imagine themselves relaxed and coping effectively with the situation (for about another 20 seconds). Finally, clients stop imagining the situation and return to focusing solely on the process of relaxation (about 20 seconds). SCD is aimed at having clients repeatedly practise relaxation applications to the types of situations that trigger anxiety. Although this technique may lead to some extinction of the connection between anxiety and specific triggers, its effectiveness is probably due more to the strengthening of adaptive coping responses to representative anxiety cues. The more clients practise SCD, the greater the likelihood that they will remember to use their CBT coping responses during daily living. The paragraph below is an example of the sort of therapist patter that can be used when conducting formal insession SCD practice. 160 Michelle G. Newman and Thomas D. Borkovec When I begin to present the images, try to picture yourself as if you are actually in the situation, picturing the associated sights, smells, and sounds. In addition, please raise your finger at the first moment that you begin to feel any tension or anxiety. Once you have signalled, continue to picture yourself in the situation that I am depicting, and hold your finger raised until you are aware that your anxiety is dissipating . . . Visualise yourself at home near your front door about to leave for work . . . Imagine that as you reach into your purse to get your keys, they are not in their usual place . . . Imagine thinking, ‘What if I am late?’ . . . ‘What if my boss goes to look for me, and he notices I haven’t arrived yet?’ . . . You can feel the anxiety beginning to increase as your mind is thinking these things . . . Your tension and anxiety are escalating as you continue to worry about being late . . . Imagine that your heart is racing faster and faster. When the client raises their finger to indicate that they are feeling anxious, or after you have been presenting the scene for 60 seconds and they have not signalled anxiety, instruct the client to begin to apply their coping strategies: Now continue to imagine yourself at home near your front door, as you imagine yourself letting go of the anxiety . . . Just visualise yourself letting go of and relaxing away the anxiety completely . . . Calm and peaceful, quiet and relaxed . . . Imagine that relaxation is reducing the speed of your heart, the tension in your muscles . . . Anxiety dissipating, just melting away . . . Your muscles are becoming more and more smooth and regular . . . Breathing becoming more and more even . . . As you imagine yourself at home, calmly trying to determine where you may have left your keys . . . Relaxing more and more and focusing on finding your keys . . . If the client does not signal that the anxiety cues have dissipated, the therapist can continue to present the scene as the client pictures themselves coping with it for an additional 20 seconds. However, if after an additional 20 seconds, the client still does not indicate relaxation, the therapist can discontinue their presentation of the image and have the client focus solely on relaxation. If the client does indicate that their anxiety has dissipated by lowering their finger, the therapist asks the client to continue picturing themselves in the scene and coping effectively: Just continue imagining yourself at home calmly retracing your steps . . . Relaxing more and more completely . . . Your breathing becoming even more smooth and regular . . . Loosening up and becoming more and more comfortably and deeply relaxed . . . Nothing to do but to enjoy the pleasant sensations of relaxation as the relaxation process continues to take place as you imagine yourself calmly at home focusing on finding your keys. Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and GAD 161 Then instruct the client to stop visualising that scene and to continue focusing on the relaxation for another 20 seconds: Allowing the relaxation process to continue . . . Calm and quiet . . . Breathing smoothly and slowly, calm, heavy, and relaxed . . . Peaceful relaxed . . . nothing to do now but to simply enjoy the pleasant feelings of relaxation. During each in-session practice, the therapist should present the image at least three times or until the client indicates the absence of anxiety in response to two consecutive presentations. After the client has practised SCD for a period of time, the therapist can introduce several anxiety cues associated with any one image. The ultimate goal of this technique is for the client to be able to picture all of the cues that are representative of his or her anxiety triggers, either with no anxiety or being able to rapidly terminate the anxiety. Of course, every single cue cannot be paired with every anxiety-provoking situation. However, the therapist should make the effort to cover a sample of representative environmental contexts as well as all of the internal anxiety cues the client typically experiences. Following the first formal SCD practice that is conducted in the session with the client, he or she is asked to use the technique at the end of his/her daily relaxation practice sessions. The client starts by using the image that was introduced in the last therapy session after each relaxation practice. He or she can use this same image until it is no longer anxiety-provoking, at which time another anxiety-provoking image can be substituted. Eventually, when the client has begun to master SCD, the therapist can introduce some variations of this technique. For example, periodically when the client is describing a situation that they are worried about (e.g., an upcoming presentation to a group), the therapist may suggest that they briefly close their eyes and imagine themselves in the situation and then imagine themselves effectively coping with the situation (e.g., “as you relax away your anxiety, imagine yourself standing in front of the group, giving an excellent presentation”). Another helpful variation involves the sequential presentation of a series of representative anxiety-provoking images, with no advance warning to the client. This introduces the same sort of surprise that is prototypical of real life. As the therapist is presenting the images, clients imagine themselves effectively coping with each one. Cognitive therapy Cognitive therapy (CT) is based on the idea that our emotions are often the result of how we interpret situations around us. The importance of this technique for GAD clients is demonstrated by studies showing that these 162 Michelle G. Newman and Thomas D. Borkovec individuals have a tendency to make negative interpretations of and predictions from ambiguous and neutral information (Mathews, 1990; Mathews & MacLeod, 1994). In addition, the current Penn State GAD project has found that when clients monitor the actual outcomes of events that they worried about, 84% of the situations turned out better than they predicted and they coped better than predicted in 78% of the remaining situations. In only 3% of all worries did the core feared event (“The predicted bad event will occur, and I won’t be able to cope with it”) actually happen. This suggests that GAD clients may be biased toward inaccurately negative interpretations which remain uncorrected by their positive experiences. Cognitive therapy teaches clients to actively correct inaccurately negative interpretations by attending to the evidence around them. Prior to having clients engage in specific techniques of cognitive therapy, therapists must help them discover the link between thoughts and anxiety. This link will become increasingly clearer as clients begin to track and identify the variety of thoughts and images associated with their anxiety and worry. The therapist can point out that when they are worrying about the future or the past, they are creating an illusion. Although these future and past events do not exist now, clients still react emotionally as if the events are actually occurring. Thus, they create many of their anxious experiences merely by thinking worrisome thoughts and imagining catastrophic scenes. CT for anxiety disorders (Beck & Emery, 1985) involves a series of steps that clients can follow. The first step is for clients to concretely identify the thoughts, images, predictions, interpretations and beliefs that are creating anxiety. Next, they treat their thoughts like hypotheses rather than facts and, as a scientist would, logically gather evidence to support and refute their thoughts. As part of this evidence, they can estimate the probability that their feared outcome will actually happen. The probability of something happening in the future is often best estimated by how frequently it has happened in the past, and clients can search their personal history to come up with a meaningful estimate of the chances for the occurrence of the feared event. Distancing methods can also be used by clients to gather evidence. This method has clients logically analyse the thoughts and predictions of another person rather than of themselves (e.g., a friend or acquaintance, a hypothetical stranger, or the therapist role-playing someone else). Such distancing reduces the likelihood of the reliance on habit and allows clients to think more clearly and to reason more accurately. Once all of the evidence has been gathered, the next step is to examine it carefully to determine whether the original thought is accurate (e.g., is there more evidence in support or in opposition of their thought?). Next, they try to come up with multiple alternative interpretations that are less anxiety-provoking but equally or more likely to be true based on the evidence they have. They then choose the least anxiety-provoking, most believable alternative self-statement and substitute it for the original anxiety-provoking one. In the future, whenever they notice Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and GAD 163 themselves using the old interpretation, they can try to substitute the alternative that may be more true. If they are not convinced that the alternative view is accurate, they can try testing out the perspective by conducting experiments during their daily life to get the evidence they may need. The main goal of CT for GAD is to help clients create more balanced perspectives. CT is not meant to teach clients to look at the world in an unrealistically positive way (e.g., through rose coloured glasses), but rather to view the world more accurately. The most important therapeutic task is for the client to objectively view all encountered situations, encode all new information, and to use this information to reconstruct their world view. Our clinical experience reveals that GAD clients typically show two types of error thinking that can block this goal. They tend to focus on mental illusions related to the past or the future, and they excessively attend to negative aspects of their situation. The therapeutic task, therefore, is to help clients encode the positive information around them and to become more objective in their assessment of current, past, and future reality. To help them determine the accuracy of particular perspectives, clients are asked to adopt two rules. The first rule is that they should avoid only probable dangers rather than every conceivable outcome. If the danger does not have a high likelihood of occurrence, there are usually more accurate predictions available. This is a very important rule as GAD clients are very good at justifying their fears (e.g., “yes, but it is possible that it could happen”). The therapist can tell clients that there are lots of things that could happen but it is not advantageous to worry about every single one of those things. One way to illustrate this point is to describe what life might be like if we worried about everything that could happen. For example, what if every time I picked up a pencil, I worried that the point would break, and every time I climbed into a car, I worried that I would get into a car accident, and every time I took a shower, I worried that I would slip and fall, etc. In fact, if I didn’t set limits for myself, I could worry about everything all the time. If the danger does have a high likelihood of occurrence, the client is asked to rate how well he or she could cope with the feared outcome. This question is linked with the idea that even when the feared outcome is likely, we often underestimate our ability to cope it. The second rule is that clients should suspend judgement until they have evidence to support a particular conclusion. This rule can be particularly difficult to follow since GAD clients often believe that viewing situations in the most negative light is actually advantageous. For example, a common belief is that anticipating the worst possible outcome helps them to be more prepared for it and less disappointed if it actually happens. For such a perspective, the therapist might want to do a cost–benefit analysis. In many cases the cost of always expecting the worst is sleeplessness, chronic anxiety, chronic fatigue, depressed mood, etc. In addition, most situations never really turn out exactly as expected; it is therefore not possible to try to prepare in 164 Michelle G. Newman and Thomas D. Borkovec advance. Moreover, even when we expect the worst, we are not able to prevent feelings of sadness or disappointment when it happens. Thus, we have spent a longer time period feeling anxious and sad, with no true advantage. To help GAD clients to become more objective in their assessment of reality, it is useful to ask them to take on the role of scientists in evaluating the validity of their worries. The clients are invited to monitor the content of their worry on a daily basis, to test whether their negative predictions have been valid, and to evaluate how well they were able to cope when their predictions of negative events were correct. Such detailed and specific assessment of the clients’ worry, predictions, and coping abilities frequently provides a direct challenge of clients’ distorted thoughts. After such a “scientific assessment” of their worry, clients typically realise that most of their predictions were unfounded or that they were able to handle the predicted negative event better than they thought. It is not unusual for a client to realise that even negative events are not all that bad and that sometimes the worst things can turn out to be the best thing for them. As he had predicted, one client failed to be offered a job for which he had recently been interviewed. A few weeks later, however, he was offered what he had for a long time considered to be his “dream job”. If he had not failed at getting the first job, he would never have been able to see his dream come true. At the beginning of CT it may be difficult for clients to generate alternative ways of thinking or believing. Their schematic views of themselves, the world, and the future have become old and powerful habits that have allowed them to function well enough in their lives. However, with a greater number of perspectives available, clients have more choices than when their perspectives are determined by habit. As they are learning to consider various perspectives, clients may find it helpful to focus first on neutral topics rather than on internal or external events that generally trigger their anxiety spiral. Therapists may ask their clients to think about the good and bad things related to a rainy day, or to identify the pros and cons of getting older. This type of exercise prepares them to approach anxiety-provoking events from a variety of perspectives, rather than by rigidly committing themselves to one interpretation. Once clients have agreed to approach stressful events from a variety of perspectives, the next step is to have them weigh the advantages and disadvantages of each perspective as well as its likely accuracy based on logic, probability, and evidence. The final step is to choose the least anxiety-provoking, most accurate and believable perspective for application. As clients engage in logical analysis and generate more accurate perspectives, they sometimes report that the alternative perspective just does not feel true in the way that the old view does, even though it is more logical. There is very good reason for this. The more one imagines catastrophes, the more real they feel. In addition, GAD clients have had images of positive outcomes far less frequently, so the “feeling” that these are true is less vivid. To Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and GAD 165 help them make the alternative perspective feel more real, clients will find it beneficial to integrate some of the more successful realistic perspectives that they end up adopting about the self and the world into the SCD procedure. For example, as the client is picturing themselves successfully coping with a stressful situation and becoming more and more relaxed, they can also substitute a non-anxiety-provoking thought. Using the above SCD example in which the client was afraid that he or she would be late for work, they might say to themselves, “Well my boss has also seen me working late quite frequently, so he won’t mind if I’m a few minutes late this morning.” The cognitive technique of decatastrophising is an important tool when working with individuals who spend a large portion of their awakened hours fearing the worst. This involves first specifying what the clients are telling themselves is the worst outcome. Next, clients delineate the various steps that it would take to get to that point and the probability that each step could actually occur. Clients can also specify multiple alternative perspectives as well as what coping resources exist for each step. Similar to the findings that result from the “scientific assessment” described above, a detailed analysis of the outcome predicted by clients frequently reveals that the probability of real catastrophes is low and the risk of a complete lack of coping resources is virtually absent. Therapists will also find it useful to set up behavioural experiments to test clients’ negative predictions. A client who is afraid of being rejected by a woman, for example, can be invited to test his prediction by purposefully engaging in a brief conversation with this woman before the following session. In addition to helping such a client to disconfirm his worst fear, this type of experiment can also be viewed as a form of exposure. Such exposure may well be therapeutic since research evidence suggests that GAD clients engage in both cognitive and behavioural avoidance (Butler, Cullington, Hibbert, Klimes, & Gelder, 1987). Part of the goal in CT of identifying individual thoughts and images is eventually to identify recurrent, underlying themes that reflect core beliefs. One way to access core beliefs is for the therapist to ask clients if they have a rule for themselves about situations like this. For example, a client who worries about completing housework may have a rule such as, “If my whole house isn’t spotless at all times, I am a failure as a mother”. Often people develop such rules for themselves and never bother to question their value or accuracy. When core beliefs are identified, CT proceeds in similar fashion using the core beliefs as targets for intervention. The therapist can also use assessment devices developed to categorise a client’s characteristic styles of thought. In the current Penn State project, for example, all clients are administered the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (Beck, Brown, Steer, & Weissman, 1991). This scale is reviewed by all therapists prior to their first therapy session and frequently helps them to quickly identify the core schemata that are relevant to a particular client. Common schemata included fear of 166 Michelle G. Newman and Thomas D. Borkovec disapproval, the idea that they are dependent on others for their happiness, as well as excessively rigid rules about the way things “should” be. The ultimate goal of CT with GAD is to help clients create as much freedom as possible within the restraints of their everyday lives. This includes becoming less influenced by and reactive to other people’s opinions of them and more flexible with regard to the rules they use to evaluate themselves and others. At the core of this freedom is helping the client to gradually shift their attention from extrinsic (e.g., how will other people judge me) to the intrinsic rewards (e.g., how can I discover joy in this task at the moment I am doing it). By re-focusing their attention to the joy of the present moment and shifting away from their focus on the desired outcomes, clients discover that they spend much less time generating worrisome thoughts about potential consequences and more time enjoying the moments of their lives. For example, a person who is writing a paper can focus his or her attention on how that paper may be evaluated by others and the hope that the paper will bring some concrete reward (e.g., publication, a high grade, funding, a raise in salary). However, such a focus on potential rewards also brings about the focus on the fear that the reward may not be given to them. This may lead to performance anxiety which is likely to interfere with their ability to accomplish the task at hand. On the other hand, clients can focus their attention, on the task of writing, its intrinsic meaning, or how it can be done in a beautiful, skilful, or joyful manner. The role of the therapist is to help clients rediscover for each activity or role what it is that is pleasureful or intrinsically satisfying in them. The client can also apply such an alternative perspective as they are practising SCD. This can strengthen their inclination to apply such views on a daily basis. Once clients have learned to successfully use more adaptive cognitions in their daily lives, the therapist can introduce the additional goal of expectancyfree living. Of course, certain circumstances do require human beings to anticipate the future and to make plans. However, GAD clients tend to try to overplan for almost every possible consequence. Such a continual focus on the future can interfere with their processing of information and distort what they store in memory. This focus also creates frequent anxious and depressed moods in response to negative future predictions. Moreover, it is rare that a client can accurately predict the exact outcome of any situation. Therefore, as with muscular tension, the client must learn to discriminate necessary and helpful planning from future anticipation that is not helpful to them. One concept that can be introduced is the idea of diminished return. A future focus is only helpful as long as the person is not feeling anxious and is engaged in helpful problem-solving. However, once such focus leads to anxiety, such anxiety interferes with their ability to benefit from this focus, and this is a signal to refocus their attention to the present. Such a present moment focus means trying to process events as they happen and trusting that he or she will be able to handle any consequence that happens. As with Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and GAD 167 other CBT tasks, clients can test out a present moment focus, and conduct behavioural experiments to provide evidence that focusing on the present does not diminish their ability to cope with the ongoing events in their lives. Therapists frequently discover that GAD clients often have the ability to come up with multiple reasons for fearing and planning for the future. They have spent so much time anticipating every possible negative outcome that they have developed infinite detailed reasons as to why the world is a dangerous place and why they may not be able to cope. They are thus very good at countering logic and evidence. As a result, therapists can find themselves in a non-victorious debate with their clients as they use examples from their clients’ life in an attempt to teach them how to apply CT. If therapists find themselves in a situation in which they have come up with multiple alternative perspectives about a situation that are rejected, it may not be beneficial to continue to try to “convince” the client that they should believe something that just does not feel true to them. Such a rigid pursuit can lead to frustration, create alliance ruptures, and ultimately becomes counter-therapeutic (Safran & Segal, 1990). Instead, it is important for the therapist to be as flexible as possible, to try a number of options, and not to focus on the outcome of getting the client to accept an alternative perspective after each example. As they do this, therapists can watch the client to determine whether any of the options they have tried are helpful. The ultimate outcome is simply to show the client that there are multiple alternative ways of viewing most situations and that they can learn to think more flexibly. Treatment outcome research Controlled investigations of GAD treatment have only occurred recently. This is because the diagnostic criteria were changed several times. Another reason is that exposure-based cognitive behavioural therapies for anxiety were predicated on the theory that anxiety was maintained via escape or avoidance. However, the maintenance of GAD could not be easily explained by the same sort of avoidance that had been thought to maintain other anxiety disorders. Whereas other anxiety disorders were associated with behavioural avoidance as a means of coping with externally feared situations, GAD clients relied on conceptual activity (i.e., worry) to avoid or prepare for ways to cope with possible future danger (Beck & Emery, 1985). Because such danger existed only in their minds, behavioural avoidance was not an available response. As a result, internal cues were more important, whereas the therapeutic value of exposure techniques was less clear. To resolve this dilemma, the first GAD interventions relied primarily on relaxation techniques which clients applied as a general coping response whenever they felt anxious. The first clinical trials began with non-DSM-defined “general anxiety”. These studies generally found that combined anxiety management treatments 168 Michelle G. Newman and Thomas D. Borkovec were associated with sustained improvements that were sometimes better than the effects of individual components. There was also some evidence that the addition of cognitive therapy techniques led to increments in followup improvement (Durham & Turvey, 1987; Lindsay, Gamsu, McLaughlin, Hood, & Espie, 1987). Twelve subsequent treatment studies used DSM criteria to select GAD participants. All of these studies included cognitive behavioural therapies in most or all of their comparison conditions. This research supported the efficacy of CBT as a treatment that leads to clinically significant change, with sustained improvement up to a year later (Borkovec & Whisman, 1996). These studies also indicate that CBT therapies are associated with low drop-out rates, reductions in use of medication, and the largest effect sizes when compared to no treatment, analytic psychotherapy, pill placebo, non-directive therapy, and placebo therapy. Although several investigations have not found differences between combined CBT and either cognitive therapy or behaviour therapy alone, others have documented its superiority immediately after treatment or at long-term follow-up. As we have mentioned at the start of this chapter, CBT currently stands as the only therapy method for GAD that has been empirically validated (Chambless et al., 1996). Despite support for the effectiveness of CBT, there is still room for improvement. Only about 50% of treated clients exhibit clinically significant change at follow-up (Borkovec & Whisman, 1996; Chambless & Gillis, 1993). In addition, despite the application of fairly stringent research methodology (e.g., frequent use of manuals, diagnostic interviews, integrity checks, and expectancy/credibility assessments), a majority of studies have had significant limitations. For example, GAD is the anxiety disorder with the lowest interrater agreement (Barlow & DiNardo, 1991), yet only three studies required two independent diagnostic interviews. Such a lapse may have led to the inclusion of inaccurately diagnosed individuals (as many as 25–30%). Moreover, the superiority of combined CBT to non-specific or individual CBT components has not been consistently supported. This may be due to an inflated number of false positive GAD diagnoses. The issue of non-specific effects and the contribution of individual CBT elements was addressed in a recent comparison of applied relaxation, CBT (applied relaxation, self-control desensitisation, and brief CT), and a reflective listening control condition (Borkovec & Costello, 1993). Contrary to previous research, GAD was diagnosed using two independent structured interviews. Moreover, this study employed objective ratings which showed that therapists adhered to a tightly structured protocol and that the provided therapy was of a high quality. Results of this study supported the superiority of applied relaxation and CBT to reflective listening at post-test. At 12month follow-up, however, those treated with reflective listening had deteriorated, those who received applied relaxation had maintained their gains, and those in the CBT condition showed even further improvement. Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and GAD 169 A larger number of clients in the combined CBT condition also showed clinically significant change than in the other two conditions. These findings supported the view that CBT for GAD was optimal when it employed multiple techniques to target each of the cognitive, physiological, and imaginal response systems. In a recently completed therapy study at Penn State (Borkovec et al., in press), three therapy conditions were compared. One condition was focused on applied relaxation and self-control desensitisation, the second on cognitive therapy, and the third on their combination. Therapist contact time was oubled from the previous trial to determine whether this would lead to a larger percentage of clients who would achieve high endstate functioning. Findings suggest that similar to the previous study, no more than 50% of the clients in the three therapy conditions achieved high endstate functioning, and all three therapies were equally effective. These results do not support existing evidence from prior research that long-term maintenance is best produced by a combined CBT that targets the cognitive, physiological, and imaginal response systems. However, it is possible that this result is due to the doubling of client contact time, which may have increased the efficacy of the cognitive therapy and behavioural therapy component conditions. However, this study also indicates that doubling CBT therapist contact time does not result in any incremental benefit. The impact of therapy at follow-up was not significantly different from previous studies using 50% less therapist contact. Given this result, as well as the current climate of costcontainment, future research might benefit from a determination of the minimum number of therapy sessions required to achieve the best therapeutic result possible. Research on GAD treatment might also benefit from the assessment of other techniques to increase the efficiency and costeffectiveness of CBT for GAD (e.g., Newman, 2000b; Newman, Consoli, & Taylor, 1997). An ongoing study is currently being conducted by the first author of this chapter examining the effect of computer-assisted CBT combined with reduced therapist contact time in a group setting. In a pilot study of this approach, three out of three group members no longer met diagnostic criteria for GAD at 6-month follow-up (Newman, 1999). Future research might also benefit from the examination of therapeutic techniques that have not yet been empirically tested to develop more potent therapies for GAD. Evidence from the ongoing Penn State study indicates that a fertile area of investigation may be therapy techniques that target interpersonal problems (Newman, Castonguay, Borkovec, & Molnar, in press). Specific types of interpersonal difficulties, such as being domineering, overly nurturant, and intrusive, did not improve as a result of therapy and negatively predicted outcome. This suggests that a therapeutic intervention aimed at interpersonal problems may increase the effectiveness of CBT. A preliminary study is currently being conducted to test this hypothesis (Newman, Castonguay, & Borkovec, March 1999). 170 Michelle G. Newman and Thomas D. Borkovec Acknowledgement This research was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health Research Grant MH-39172 to the second author. Correspondence can be addressed to Michelle G. Newman, Department of Psychology, Penn State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA. References American Psychiatric Association (1980). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition. Washington, DC: Author. American Psychiatric Association (1987). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised 3rd Edition. Washington, DC: Author. American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. Washington, DC: Author. Barlow, D. H. (1988). Anxiety and its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic. New York: Guilford Press. Barlow, D. H. & DiNardo, P. A. (1991). The diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder: Development, current status, and future direction. In R. M. Rapee & D. H. Barlow (Eds.), Chronic Anxiety: Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Mixed Anxiety–Depression. New York: Guilford Press. Beck, A. T., Brown, G., Steer, R. A., & Weissman, A. N. (1991). Factor analysis of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale in a clinical population. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 3, 478–483. Beck, A. T. & Emery, G. (1985). Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Perspective. New York: Basic Books. Borkovec, T. D. (1994). The nature, functions, and origins of worry. In G. C. L. Davey & F. Tallis (Eds.), Worrying: Perspectives in Theory, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: John Wiley and Sons. Borkovec, T. D., Abel, J. L. & Newman, H. (1995). The effects of therapy on comorbid conditions in generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 479–483. Borkovec, T. D. & Costello, E. (1993). Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive behavioural therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 611–619. Borkovec, T. D. & Inz, J. (1990). The nature of worry in generalized anxiety disorder: A predominance of thought activity. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28, 153–158. Borkovec, T. D. & Mathews, A. M. (1988). Treatment of nonphobic anxiety disorders: A comparison of nondirective, cognitive, and coping desensitization therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 877–884. Borkovec, T. D., Mathews, A. M., Chambers, A., Ebrahimi, S., Lytle, R. & Nelson, R. (1987). The effects of relaxation training with cognitive therapy or nondirective therapy and the role of relaxation-induced anxiety in the treatment of generalized anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinic al Psychology, 25, 883–888. Borkovec, T. D. & Newman, M. G. (1998). Worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In P. Salkovskis, A. S. Bellack & M. Hersen (Eds.), Comprehensive Clinical Psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 439–459). New York: Pergamon Press. Cognitive behavioural therapy for worry and GAD 171 Borkovec, T. D., Newman, M. G., Pincus, A. L., & Lytle, R. (in press). A component analysis of cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder and the role of interpersonal problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. Borkovec, T. D. & Whisman, M. A. (1996). Psychological treatment for generalized anxiety disorder. In M. R. Mavissakalian & R. F. Prien (Eds.), Long-term Treatments of Anxiety Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Borkovec, T. D., Wilkinson, L., Folensbee, R. & Lerman, C. (1983). Stimulus control applications to the treatment of worry. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21, 247–251. Brown, T. A. & Barlow, D. H. (1992). Comorbidity among anxiety disorders: Implications for treatment and DSM-IV. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 835–844. Brown, T. A., Barlow, D. H. & Liebowitz, M. R. (1994). The empirical basis of generalized anxiety disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1272–1280. Butler, B., Cullington, A., Hibbert, G., Klimes, I. & Gelder, M. (1987). Anxiety management for persistent generalized anxiety. British Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 535–542. Chambless, D. L. & Gillis, M. M. (1993). Cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 248–260. Chambless, D. L., Sanderson, W. C., Shoham, V., Johnson, S. B., Pope, K. S., CritsChristoph, P., Baker, M., Johnson, B., Woody, S. R., Sue, S., Beutler, L., Williams, D. A. & McCurry, S. (1996). An update on empirically validated therapies. The Clinical Psychologist, 49, 5–18. Durham, R. C. & Turvey, A. A. (1987). Cognitive therapy vs behaviour therapy in the treatment of chronic generalised anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 25, 229–234. Goldfried, M. R. (1971). Systematic desensitization as training in self-control. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 37, 228–234. Heide, F. J. & Borkovec, T. D. (1983). Relaxation-induced anxiety: Paradoxical anxiety enhancement due to relaxation training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 171–182. Heide, F. & Borkovec, T. D. (1984). Relaxation-induced anxiety: Mechanisms and theoretical implications. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 22, 1–12 Hoehn-Saric, R., McLeod, D. R., & Zimmerli, W. D. (1989). Somatic manifestations in women with generalized anxiety disorder: Physiological responses to psychological stress. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46, 1113–1119. Kendler, K. S., Neale, M. C., Kessler, R. C., Heath, A. C. & Eaves, L. J. (1992). Generalized anxiety disorder in women: A population-based twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49, 267–272. Lindsay, W. R., Gamsu, C. V., McLaughlin, E., Hood, E. & Espie, C. A. (1987). A controlled trial of treatment for generalized anxiety disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 26, 3–15. Mathews, A. (1990). Why worry? The cognitive function of anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28, 455–468. Mathews, A. & MacLeod, C. (1994). Cognitive approaches to emotion and emotional disorders. Annual Review of Psychology, 45, 25–50. Newman, M. G. (1999). The clinical use of palmtop computers in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 6, 222–234. 172 Michelle G. Newman and Thomas D. Borkovec Newman, M. G. (2000a). Generalized anxiety disorder. In M. Hersen & M. Biaggio (Eds.), Effective Brief Therapies: A Clinician’s Guide (pp. 157–178). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Newman, M. G. (2000b). Recommendations for a cost offset model of psychotherapy allocation using generalized anxiety disorder as an example. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 549–555. Newman, M.G. & Borkovec, T. (1995). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. The Clinical Psychologist, 48, 5–7. Newman, M. G., Castonguay, L. G., & Borkovec, T. D. (1999, March). New dimensions in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: Interpersonal focus and emotional deepening. Paper presented at the Society for the Exploration of Psychotherapy Integration, Miami, FL. Newman, M. G., Castonguay, L. G., Borkovec, T. D., & Molnar, C. (in press). Integrative psychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder. In R. Heimberg, D. Mennin, & C. Turk (Eds.), The Nature and Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder. New York: Guilford Press. Newman, M.G., Consoli A. & Taylor, C.B. (1997). Computers in the assessment and cognitive-behavioral treatment of clinical disorders: Anxiety as a case in point. Behavior Therapy, 28, 211–235. Safran, J. & Segal, Z. V. (1990). Interpersonal Process in Cognitive Therapy. New York: Basic Books. Wittchen, H.-U., Zhao, S., Kessler, R. C. & Eaton, W. W. (1994). DSM-III-R generalized anxiety disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 355–364. Chapter 7 Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch Introduction The apparent increasing incidence of both anorexia and bulimia nervosa has resulted in a surge of interest in effective treatment methods among a wide range of health professionals. The aim of this chapter is to provide a practical overview of treatment principles which have been identified as useful in the management of these eating disorders. Emphasis will be given to cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) methods which may be justified for bulimia nervosa by the growing body of empirical literature indicating that these methods are effective for many patients (Fairburn, 1985; Fairburn, Marcus, & Wilson, 1993; Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 1997; Walsh, Wilson, Loeb, Devlin, Pike, Roose, Fleiss, & Waternaux, 1997). There is less empirical evidence for anorexia nervosa since comparative treatment trials have not been reported. The rationale for the application of CBT interventions to anorexia nervosa is based almost entirely on clinical experience (Garner, 1986, 1988; Garner & Bemis, 1982, 1985; Garner & Rosen, 1990; Garner, Vitousek, & Pike, 1997; Vitousek & Orimoto, 1993). Definition of terms Anorexia nervosa The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (APA, 1994), are summarised as follows: (1) refusal to maintain a body weight over a minimally normal weight for age and height (e.g., weight loss leading to maintenance of a body weight less than 85% of that expected, or failure to make expected weight gain during period of growth, leading to body weight less than 85% of that expected); (2) intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight; (3) disturbance in the way that body weight, size, or shape is experienced; and (4) amenorrhoea in females (absence of at least three menstrual cycles). The DSM-IV criteria formalise earlier overlapping 174 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch conventions for subtyping anorexia nervosa into restricting and bingeeating/purging types based on the presence or absence of the bingeing and/or purging (i.e., self-induced vomiting, or the misuse of laxatives, or diuretics). It is important to note that patients move between these two subtypes with chronicity leading toward aggregation in the binge-eating/purging subgroup (Hsu, 1988). Bulimia nervosa The diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (APA, 1994), are summarised as follows: (1) recurrent episodes of binge-eating (binge-eating is characterised by a sense of lack of control over eating a large amount of food in a discrete period of time); (2) recurrent, inappropriate compensatory behaviour in order to prevent weight gain (i.e., vomiting; abuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications; fasting or excessive exercise); (3) a minimum average of two episodes of binge-eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviours per week for the past three months; (4) self-evaluation unduly influenced by body shape and weight; and (5) the disturbance does not occur exclusively during episodes of anorexia nervosa. Bulimia nervosa patients are further subdivided into purging type and non-purging type, based on the regular use of selfinduced vomiting, laxatives, diuretics or other medications, fasting or excessive exercise. Eating disorders not otherwise specified (NOS) Individuals who have eating disorders that are clinically significant but who fail to meet one or more of the criteria required for a formal diagnosis of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa have been given the diagnostic designation “eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS)”. For example, the EDNOS diagnosis is given for individuals who meet all of the criteria for anorexia nervosa except that they have regular menses or a weight that is in the normal range. It is also assigned when all of the criteria for bulimia nervosa are met except that the binge frequency is less than an average of twice a week for a duration of less than three months. It is also applied to patients who are at a normal body weight who regularly engage in inappropriate compensatory behaviour after eating small amounts of food (i.e., in the absence of binge-eating) or who repeatedly chew and spit out large amounts of food. Finally, the eating disorder NOS category is applied to patients who have what has been referred to as the “binge-eating disorder”, characterised by recurrent episodes of binge-eating in the absence of the inappropriate compensatory behaviours evident in bulimia nervosa. Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 175 Causal factors Earlier psychological theories attributing eating disorders to exclusive developmental, familial, cultural, or personality factors have tended to be replaced by “multidimensional” models which emphasise that the characteristic symptom picture may evolve from a different blend of predisposing factors for different individuals. Accordingly, symptom patterns represent final common pathways resulting from the interplay of three broad classes of predisposing factors: (1) cultural, (2) individual (psychological and biological), and (3) familial. These causal factors are presumed to combine with one another in different ways that lead to the development of eating disorders. The precipitants are less clearly understood, except that dieting is invariably an early element. Perhaps the most practical advancements in treatment have come from increased awareness of the perpetuating effects of starvation, with its psychological, emotional, and physical consequences (Garner, 1997). This general aetiological model has led to various treatment formulations. The cognitive behavioural approach will be the focus of this chapter because it has received comparatively greater empirical and clinical support over the last decade. Duration and structure of therapy The duration of treatment for bulimia nervosa is typically about 20 weeks (Fairburn et al., 1993); however, it is well recognised that difficult patients may require a longer period of care (Wilson et al., 1997). In contrast, treatment for anorexia nervosa typically lasts 1–2 years (Garner et al., 1997; Pike, Loeb, & Vitousek, 1996). The longer duration of treatment is required in most cases of anorexia nervosa because of the time required to overcome motivational obstacles, achieve appropriate weight gain, and occasionally implement inpatient or partial hospitalisation. The structure of individual therapy sessions is similar for bulimia nervosa (Fairburn et al., 1993) and anorexia nervosa (Garner et al., 1997). In each session: (1) an agenda is set, (2) self-monitoring is reviewed, (3) dysfunctional behaviours and schemas are identified and changed, (4) the session is summarised, and homework assignments are specified. For anorexia nervosa additional components are added such as checking the patient’s weight, discussion of weight within the context of goals, review of physical complications and meal planning (Garner et al., 1997). Also, in anorexia nervosa, modifications must be made to the format of therapy to take into consideration the special needs such as the age of the patient and the clinical circumstances, and to determine the format of meetings as individual, family, or a mix of family and individual meetings. 176 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch General treatment principles There are several general principles that should be considered central to any treatment approach to eating disorders and they will only be briefly mentioned here because they have been elaborated in depth elsewhere (Fairburn, 1985; Garner, 1986; Garner & Bemis, 1982, 1985; Garner & Isaacs, 1985; Garner, Garfinkel, & Bemis, 1982; Garner, Garfinkel, & Irvine, 1986). These include the importance of the therapeutic relationship, cultivating motivation for treatment, differences in treatment for the two main eating disorders, and the two track approach to treatment. The therapeutic relationship Although Beck and his colleagues (Beck, 1976; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) have emphasised that CBT treatment, as with other approaches, presupposes a trusting, warm, and empathic relationship with the therapist, this essential ingredient is sometimes overlooked in discussions of the technical aspects of cognitive therapy. Rather than representing a “non-specific” element in the treatment of eating disorders, a strong therapeutic relationship should be regarded as integral to change. This is particularly important in anorexia nervosa where the patient may enter treatment with considerable resistance to change (Garner et al., 1997). Motivation for treatment Enlisting motivation for treatment can be difficult with eating disorder patients since certain symptoms like restrictive dieting are ego-syntonic. It is generally agreed that motivation is more difficult to cultivate with anorexia nervosa since these patients are reluctant to commit to the main goal of treatment, namely weight gain. This contrasts with bulimia nervosa where patients usually accept elimination of binge-eating as the primary goal of treatment. Specific strategies for cultivating and sustaining motivation for change with anorexia nervosa are beyond the scope of this chapter; however, they have been detailed elsewhere (Garner et al., 1997). Differences in treatment of anorexia versus bulimia nervosa Anorexia and bulimia nervosa share many features in common so it is not surprising that cognitive approaches to therapy for both disorders overlap to a significant degree. Similar cognitive restructuring approaches are recommended for both disorders to address characteristic attitudes about weight and shape. Education about regular eating patterns, body weight regulation, starvation symptoms, vomiting and laxative abuse is a strategic element Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 177 in the treatment of both disorders. Finally, similar behavioural methods are also required, particularly for the binge-eating/purging subgroup of anorexia nervosa patients. However, key distinctions can be made between these disorders. Standard CBT for bulimia nervosa must be altered to address specific clinical features more pertinent to anorexia nervosa. For example, with anorexia nervosa patients, the style, pace, and content of CBT needs to be modified to address motivational obstacles, weight gain as a target symptom, the use of meal planning versus self-monitoring, the need to integrate family therapy for younger patients and interpersonal themes that emerge over a much longer typical course of treatment. These will not be discussed in detail here since they have been reviewed elsewhere (Garner et al., 1997). Two track approach to treatment Throughout all stages of treatment we recommend a “two track” approach in which the first track pertains to issues related to weight, bingeing, vomiting, strenuous dieting, and other behaviours aimed at weight control. The second addresses the psychological context of the disorder including beliefs and thematic underlying assumptions which are relevant to the development or maintenance of the disorder. In practice, there is considerable switching back and forth between these content areas in therapy. Greater emphasis is placed on track one early in therapy, emphasising the interdependence between mental and physical function. Treatment gradually shifts to track two issues as progress is made in the areas of eating behaviour and weight. Selection of treatment approaches Rather than assume that all treatments are equally applicable to all eating disorder patients, clinical writers have shown a growing interest in “steppedcare”, “decision-tree” or “integration” models which rely on fixed or variable rules for the delivery of the various treatment options (see Garner & Needleman, 1997, for a review). According to the stepped-care model, a patient is provided with the lowest step intervention, one that is least intrusive, dangerous, and costly, even if the lowest step intervention does not have the highest probability of success. In contrast, a decision-tree approach provides numerous choice points resulting in different paths for treatment, depending on the clinical features of the patient as well as the response to each treatment delivered. Using a combined decision-tree and integration model, Garner and Needleman (1997) recommend an educational approach as the initial intervention for the least disturbed bulimia nervosa patients, and integrate this into other forms of treatment for other eating disorder patients, including those with anorexia nervosa. Family therapy is recommended as the 178 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch primary treatment modality if the patient is young and living at home. Pharmacotherapy is considered as an option in bulimia nervosa (but not anorexia nervosa) when patients fail to respond to psychosocial treatments. For patients with serious medical complications or for those who need to gain substantial body weight, inpatient treatment is recommended as the initial intervention. Day treatment is suggested for patients who do not require hospitalisation but do need a high level of treatment intensity and meal supervision. This model for the integration and sequencing of treatment represents an attempt to articulate the decision-making process in delivering different forms of treatment for both of the main eating disorders. At this time, proposals for integrating and sequencing different forms of treatment have not been empirically tested in the eating disorder area. This is partly due to the formidable practical and theoretical impediments to a research protocol required to test complex stepped-care, decision-tree and integration models. Nevertheless, existing treatment research combined with current clinical knowledge provides a foundation for rational recommendations regarding the selection of treatments in the management of eating disorders. Cognitive behavioural theory There is now broad agreement that the rationale for CBT for eating disorders rests primarily on the assumption that restrictive dieting (largely in response to cultural imperatives to meet unrealistic standards for body weight) is in direct conflict with the internal biological systems responsible for the homeostatic regulation of body weight (Garner, 1997; Garner, Rockert, Olmsted, Johnson, & Coscina, 1985). Given the current cultural pressures for thinness, it is not hard to understand how women, particularly those with persistent self-doubts, could arrive at the conclusion that personal failings are to some degree related to weight or that the attainment of slenderness would measurably improve self-estimation. It has been asserted that for some who develop eating disorders, the motivating factors do not seem to go beyond a literal or extreme interpretation of the prevailing cultural doctrine glorifying thinness. For others, however, the impetus is more complicated, with a range of psychological and interactional factors playing a role. According to the cognitive behavioural view, the dieter’s steadfast attempts to down-regulate body weight leads to a myriad of compensatory symptoms including bingeeating. Although the cognitive restructuring component of CBT has taken various forms, most rely on Beck’s well-known model which has been adapted for eating disorders (Fairburn, 1985; Fairburn, Marcus & Wilson, 1993; Garner & Bemis, 1982, 1985; Garner et al., 1997). The initial aim of cognitive restructuring is to challenge specific reasoning errors or self-destructive attitudes toward weight and shape so that the patient can relax restrictive dieting. Behavioural strategies such as self-monitoring, meal planning and exposure Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 179 to feared foods serve the overall goal of normalising food intake. The primary point of emphasis of the cognitive behavioural view has been the analysis of functional relationships between current distorted beliefs and symptomatic behaviours related to eating, weight and body shape. Particularly in the treatment of anorexia nervosa, the cognitive behavioural model has been broadened to address historical, developmental and family themes more typically described by psychodynamic and family theorists (Garner et al., 1997). It has been reasoned that motifs such as fears of separation; engulfment or abandonment; failures in the separation– individuation process; false-self adaptation; transference; overprotectiveness, enmeshment, conflict avoidance; inappropriate involvement of the child in parental conflicts; and symptoms functioning to deflect away from family conflict all involve distorted meaning on the part of theindividual, the family, or both. Although the language, style, and specific interpretations may differ sharply between the cognitive behavioural model and the dynamic models that have generated these respective formulations, it is notable that both orientations are specifically concerned with meaning and meaning systems. Moreover, the respective therapies are aimed at identifying and correcting misconceptions that are presumed to have developmental antecedents (Garner & Bemis, 1985; Guidano & Liotti, 1983). The advantage of the cognitive behavioural approach is that it allows the incorporation of developmental themes when they apply to a particular patient but does not compel all cases to fit into one restrictive explanatory system. Although there is debate about the active ingredients of CBT in the treatment of eating disorders, it is generally recognised that cognitive and behavioural strategies for normalising eating and weight are fundamental. Self-monitoring has been recommended in CBT studies as well as treatment delivered from other orientations achieving the best treatment results (Garner, Fairburn, & Davis, 1987). Self-monitoring has been considered an important component of CBT; however, some reports have specified that affective and interpersonal antecedents of binge-eating should be the target of the procedure, whereas others have focused on dietary management and changing attitudes toward weight and shape. Although both approaches to self-monitoring may prove valuable, research is needed to determine their relative effectiveness across the broad range of symptom domains. Early CBT reports emphasised the importance of exposing the patient to avoided foods (in vivo) and then preventing vomiting (Rosen & Leitenberg, 1985; Wilson, Rossiter, Kleifield, & Lindholm, 1986). Later studies indicated that the response prevention techniques did not add any benefit to cognitive procedures that do not involve response prevention (Agras, Schneider, Arnow, Raeburn, & Telch, 1989; Wilson, Eldredge, Smith, & Niles, 1991). Although there are now many studies indicating that CBT can achieve 180 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch good results with many patients, recent research has revealed that other forms of treatment, which do not address eating or weight issues at all, can lead to the amelioration of binge-eating (Fairburn et al., 1991; Fairburn, Norman, Welch, et al., 1995; Garner, Olmsted, Davis, Rockert, Goldbloom, & Eagle, 1990). In a comparison between CBT, behavioural treatment, and interpersonal psychotherapy, Fairburn et al. (1991) found that CBT was more effective than the other treatments in modifying extreme dieting, self-induced vomiting, and disturbed attitudes toward shape and body weight at the end of treatment; however, at the 12-month and 6-year follow-up there were no meaningful differences between CBT and interpersonal therapy in outcome (Fairburn et al., 1995). Table 7.1 Major content areas for cognitive therapy Phase I Building a positive therapeutic alliance Assessing key features of the eating disorder Providing education about starvation symptoms and other selected topics Evaluating and treating medical complications Explaining the multiple functions of anorexic symptomatology Differentiating the “two tracks” of treatment Presenting the cognitive rationale for treatment Giving rationale and advice for restoring normal nutrition and weight Implementing self-monitoring and meal planning Prescribing normal eating patterns Interrupting bingeing and vomiting Implementing initial cognitive interventions Increasing motivation for change Challenging cultural values regarding weight and shape Determining optimal family involvement Phase II Continuing the emphasis on weight gain and normalized eating Reframing relapses Identifying dysfunctional thoughts, schemas and thinking patterns Developing cognitive restructuring skills Modifying self-concept Developing an interpersonal focus in therapy Involving the family in therapy Phase III Summarizing progress Reviewing fundamentals of continued progress Summarizing areas of continued vulnerability Reviewing the warning signs of relapse Clarifying when to return to treatment From: Garner et al. (1997). Reproduced by permission. Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 181 Cognitive behavioural methods Beck and his colleagues have delineated a number of specific cognitive behavioural procedures for the treatment of depression and other emotional disorders (Beck, 1976; Beck et al., 1979; Beck & Emery, 1985). For an elaboration of the rationale for selecting CBT methods with eating disorders as well as the adaptation of standard procedures for anorexia and bulimia nervosa, we refer the reader to earlier publications (Fairburn et al., 1993; Garner, 1986; Garner & Bemis, 1982, 1985; Garner et al., 1997; Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 1997). Our aim here is to provide a synopsis of what we consider to be the critical components of CBT interventions. Table 7.1 contains a summary of the content areas in the treatment of anorexia nervosa from Garner et al. (1997). Presenting the cognitive rationale for treatment The main principles of cognitive therapy govern the conduct and content of therapy from the beginning: (1) primary reliance on conscious experience rather than unconscious motivation; (2) explicit emphasis on beliefs, assumptions, schematic processing and meaning systems as mediating variables accounting for maladaptive behaviours and emotions; (3) use of questioning as a major therapeutic device; (4) active and directive involvement on the part of the therapist; and (5) emphasis on work outside of the session as a means for exploring beliefs and patterns of thinking (Beck, 1976; Beck et al., 1979). Discussion of the cognitive behavioural model of treatment in anorexia nervosa must be tailored to fit the current motivation of the patient. In contrast to bulimia nervosa where symptoms are usually more distressing to the patient, at this stage in the treatment of anorexia nervosa, it is advisable to resist “teaching” the cognitive model or prematurely introducing techniques for identifying and correcting “dysfunctional beliefs”. Patients are reticent to accept a model for belief change if they prefer their ego-syntonic symptoms and are not committed to treatment. It is advisable for cognitive behavioural principles to unfold gradually in the initial phase of treatment. Education is the first “cognitive” procedure since it is explicitly aimed at changing beliefs through new or corrective information. Another way to present the cognitive model early in therapy is by example. The therapist can use the language of cognitive therapy by emphasising the importance of beliefs and assumptions in determining behaviour. Education as an initial cognitive behavioural approach Education was originally recommended as part of early descriptions of cognitive behavioural treatment for eating disorders based on the premise that 182 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch certain faulty assumptions evinced by patients were maintained, at least in part, by misinformation (e.g., Garner & Bemis, 1982). There seems to be general agreement on the utility of incorporating psychoeducation into most treatment approaches for eating disorders. There have been a number of empirical studies of the effectiveness of educational treatments in bulimia nervosa. One study comparing the presentation of this educational material in a group “classroom” format (five 90-minute sessions during a one-month period) with individual CBT indicated that, for the least symptomatic 25% to 45% patients in the sample, both treatments were equally effective on important measures of outcome (Olmsted, Davis, Garner, Eagle, & Rockert, 1991). Several specific content areas for education are reviewed below and these have been elaborated elsewhere (Garner, 1997). Education about starvation symptoms Eating disorder patients typically fail to interpret their food preoccupations, urges to binge eat, emotional distress, cognitive impairment, and social withdrawal as secondary to their severe attempts to reduce or control their weight. These symptoms are commonly thought of as specific to eating disorders; however, it is useful for the therapist to re-attribute them to dieting or starvation based on well-established research studies on these topics (Garner, 1997; Garner & Bemis, 1982). Table 7.2 lists some of the symptoms of starvation that are commonly reported by eating disorder patients. Education indicating that restrictive dieting increases the risk of bingeing Patients should also be educated about the effects of dieting on the tendency to engage in binge-eating (Polivy & Herman, 1985; Garner et al., 1985; see Garner, 1997). The fact that binge-eating can occur in the absence of primary psychopathology is surprising to many patients and can provide a springboard to a new understanding of the patient’s symptoms. Education indicating that dieting does not work Long-term follow-up studies of obesity treatment consistently indicate that 90–95% of those who lose weight will regain it within several years (Garner & Wooley, 1991). Patients can benefit from understanding that the failure of restrictive dieting in permanently lowering body weight is not related to a lapse in will-power but rather is logically consistent with the biology of weight regulation, which shows that weight loss leads to metabolic adaptations designed to return body weight to levels normally maintained. Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 183 Table 7.2 The effects of semi-starvation from the 1950 Minnesota study Attitudes and behaviour toward food Food preoccupation Collection of recipes, cookbooks, and menus Unusual eating habits Increased consumption of coffee, tea, and spices Gum chewing Binge-eating Emotional and social changes Depression Anxiety Irritability, anger Lability “Psychotic” episodes Personality changes on psychological tests Social withdrawal Cognitive changes Decreased concentration Poor judgement Apathy Physical changes Sleep disturbances Weakness Gastrointestinal disturbances Hyperacuity to noise and light Oedema Hypothermia Paraesthesia Decreased basal metabolic rate Decreased sexual interest Adapted from Garner et al. (1997). Education about the self-perpetuating cycle of bingeeating and vomiting Self-induced vomiting and laxative abuse usually begin as methods of preventing weight gain by “undoing” the caloric effects of normal eating or binge-eating. It becomes self-perpetuating because it allows the patient to acquiesce to the urge to eat but eliminates the feedback loop that would stem underlying hunger and food cravings. Education regarding laxative abuse Laxative abuse is dangerous because it contributes to electrolyte imbalance and other physical complications. Perhaps the most compelling argument for 184 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch discontinuing their use is that they are an ineffective method of trying to prevent the absorption of Calories. Education regarding physical complications Anorexia nervosa patients should have a medical evaluation to determine overall physical status and to identify or rule out physical complications associated with starvation and certain extreme weight loss behaviours (Mitchell, Pomeroy, & Adson, 1997; Sharp & Freeman, 1993). Education about eating disorders Attention should be given to clarifying myths resulting from inaccurate or conflicting reports regarding aetiology and complications of eating disorders themselves. Rationale and advice for normal nutrition and body weight Numerous methods have been advocated for helping the patient normalise eating and weight. Some are specifically designed to interrupt the bingeing and purging cycle in the subset of patients with this behaviour; others are aimed at facilitating weight gain in emaciated patients. Still others are generally applicable to patients with both of these symptom patterns. The formulation of goals related to body weight, eating behaviour and symptomatic control is dependent on the patient’s current level of motivation. If delineating concrete weight goals is beyond the patient’s level of commitment or tolerance for change, then attention needs to shift to increasing motivation for change (Garner et al., 1997). Several specific methods of normalising eating and body weight will be briefly outlined; however, the reader is encouraged to consult other primary source material for fundamentals (Fairburn, 1985; Fairburn, Marcus, & Wilson, 1993; Garner & Bemis, 1982, 1985; Garner et al., 1997). Addressing body weight in treatment The topic of body weight is approached from an entirely different perspective for anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Fairburn et al. (1993) recommend that bulimia nervosa patients “should be told that in most cases treatment has little or no effect on body weight, either during treatment itself or afterwards” (p. 376). Patients who are reluctant to eat meals or snacks due to fear of weight gain, “should be reassured that this rarely occurs . . . [and they] will discover that they can eat much more than they thought without gaining weight” (p. 378). In anorexia nervosa, this reassurance is not available since weight gain is a major aim of treatment. Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 185 In the treatment of bulimia nervosa, weekly weighing is left up to the patient, “in part because sessions can become dominated by the subject of weight at the expense of other more important issues” (Fairburn et al., 1993, pp. 372–374). In contrast, with anorexia nervosa, weight and weight gain cannot be sidestepped but must be directly confronted. Weight must be regularly checked by the therapist or another reliable source. In the case of anorexia nervosa, changes in body weight dramatically effect the interpretation of session content (Garner et al., 1997). Determine minimal body weight threshold for anorexia nervosa Anorexia nervosa patients need to be told that outpatient treatment can only proceed if their weight does not fall below a certain minimum (Garner et al., 1982). If the patient is near this minimum at the initial meetings, then this weight needs to be clearly stipulated. However, there are no absolute rules regarding this minimum, since it depends on the patient’s overall health, the presence of complications and the ability to make progress in outpatient treatment. If the patient’s weight falls below the established minimum, other more structured alternatives such as partial or inpatient hospitalisation must be available, and the focus of therapy shifts to convincing the patient that these options are necessary. Setting a target weight range as a goal in the initial meeting is dependent on the patient’s current level of motivation and commitment to treatment. The patient needs to understand the enormous biological significance of reaching a certain minimal body weight threshold and that the achievement of this weight status is essential to recovery. There are individual differences in this threshold; however, it generally corresponds to approximately 90% of expected weight for post-menarcheal women and elicits resumption of normal hormonal functioning and menstruation. Self-monitoring Self-monitoring has been consistently recommended in cognitive behavioural research studies with bulimia nervosa (Wilson et al., 1997). Self-monitoring can be helpful in establishing a regular eating routine as well as gaining control over symptoms such as binge-eating, vomiting, or laxative abuse. Self-monitoring involves keeping a daily written record of all food and liquid consumed as well as incidents of binge-eating, vomiting, laxative abuse and other extreme weight controlling behaviours. Patients are sometimes reluctant to complete self-monitoring forms because they feel ashamed of their behaviour or they feel that self-monitoring will only increase their preoccupation with food. These concerns need to be set aside with the knowledge that selfmonitoring is an extremely effective tool in obtaining control over eating 186 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch disorder symptoms. Although there is general agreement on the value of self-monitoring, recommendations related to timing and flexibility in implementing this procedure with anorexia nervosa vary. Patients who require more structure in complying with advice regarding normalising their eating patterns may benefit from meal planning in contrast to self-monitoring typically described for bulimia nervosa (Garner et al., 1997). Meal planning Meal planning involves specifying the details of eating in advance. It includes prescribing the precise foods to be consumed and their amounts, as well as the context, such as the place and times for eating. It is highly recommended that the task of meal planning occur as part of therapy rather than being necessarily relegated to a dietician or nutritionist. Meal planning and elements of prescribing normalised eating are not only aimed at renutrition, but also at probing motivation and illuminating beliefs that then become targets for cognitive interventions. There are several important components of meal planning that are particularly useful in the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Mechanical eating Eating should be done “mechanically” according to set times and a predetermined plan. Food should be thought of as “medication” prescribed to “inoculate” the patient against future extreme food cravings and the tendency to engage in binge-eating (Garner et al., 1982). Temporarily taking the decision-making out of eating is necessary early in treatment when patients are particularly prone to become overwhelmed by anxiety and guilt in problematic eating situations. Spacing eating It is important for meals to be spaced throughout the day (Garner et al., 1985). Breakfast should never be omitted and it is ideal for there to be 3 meals and 1–2 snacks spread throughout the day). It is best to confine eating to set times on the clock rather than relying on internal sensations in determining when to eat. The rationale for this type of plan is that it will minimise food cravings, urges to overeat, undereat, and loss of control. Quantity of foodstuffs The number of Calories that patients need to consume daily depends on current weight, metabolic condition, eating patterns, and tolerance for change (Garner et al., 1985). Some emaciated patients have maintained their weight Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 187 on as few as 600–900 Calories per day (Russell, 1970). Gradually increasing energy intake to achieve a 1–2 pound weight gain per week is ideal. For inpatients, the number of Calories should be adjusted to achieve a 2–3 pound weight gain per week. The prescribed diet for inpatients should never be set below 1500 Calories per day and is usually increased to 1800 to 2400 Calories within the first week. All meals need to be completed so that the patient can gain confidence that Calories prescribed can be assimilated according to the plan for weight gain or weight stabilisation. As patients shift from a hypometabolic to a hypermetabolic state, daily consumption may need to be increased to as high as 3500–4000 Calories. Patient with a personal or family history of obesity will usually need fewer Calories to accomplish the desired rate of weight gain. As outpatients, the speed of weight gain is not as important as steadily moving in the direction of gradual weight gain. Quality of foodstuffs Most patients begin treatment with considerable confusion about what constitutes “normal” eating. Patients tend to divide food into “good” and “bad” categories and this is frequently based on “nutritional myths” such as “calories from dietary fat accumulate as body fat in contrast to calories from protein and carbohydrate that get burned off ”. One goal of treatment is learning to feel more relaxed eating a wide range of foods. A weekly meal plan should gradually incorporate small amounts of previously avoided or forbidden foods. Patients should be encouraged to challenge the tendency to divide food into “good” and “bad” categories by recognising that the Calories of those foods previously considered “bad” really have no greater impact on weight than Calorie-sparing food items. Patients who engage in binge-eating should consume small amounts of the foodstuffs typically reserved for episodes of binge-eating. Again, these foods should be redefined as “medication that will help inoculate against binge-eating” by reducing psychological cravings as well as by establishing new response tendencies to foods that previously had only denoted a “blown” diet. Reframing relapses The therapist needs to prepare patients for vulnerability to relapses in bingeeating and vomiting, particularly during stressful times. After an episode of binge-eating, patients chastise themselves with conclusions like: “I have blown it; it doesn’t matter any more; since I binged this morning, the rest of the day is ruined and I might as well continue bingeing; all of my efforts are spoiled, now I must start over from square one; bingeing is evidence that I will never recover.” Patients need to be encouraged to refrain from applying dichotomous and perfectionistic thinking to relapses. They need to reframe relapses by stepping back and evaluating the episode in light of the “big picture”. The 188 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch therapist should encourage the patient to practise the four R’s (Garner et al., 1997) in reframing relapses: 1 2 3 4 Reframe the episode as a “slip” not “blown recovery”. Renew the commitment to long-term recovery. Return to the plan of regular eating without engaging in compensatory behaviours. Re-institute behavioural controls to interrupt future episodes. Identify and challenge dysfunctional thoughts, schemas and thinking patterns Throughout the course of therapy, the therapist needs to assist the patient in learning to identify dysfunctional thoughts and the processing errors that influence her perceptions, thoughts, feelings and symptomatic behaviour. Beliefs and behaviours that direct symptomatic behaviour need to be connected to more general and often implicit schemas referred to as underlying assumptions (Beck, 1976) or higher order implicit meanings or schematic models (Teasdale & Barnard, 1993). Guidano and Liotti (1983) described the progression in therapy from more superficial cognitive structures related to food and weight to “deep cognitive restructuring implying a modification of the personal identity” (p. 299). Develop cognitive restructuring skills Cognitive restructuring is a method of examining and modifying dysfunctional thinking. It has several steps (Table 7.3). Automatic thoughts, beliefs and assumptions can be pinpointed by increasing awareness of the thinking process. They may also be accessed by observing behavioural patterns. For example, restricting eating to “fat free” foods implies certain beliefs. The automatic thought may also be identified by focusing on particular situations and replaying the thinking and feeling associated with that situation. Then, the patient is encouraged to generate and examine the evidence for and Table 7.3 Steps in cognitive restructuring 1. Monitor thinking and heighten the awareness of thinking patterns. 2. Identify, clarify, distil and articulate dysfunctional beliefs or thoughts in simplest form. 3. Examine the evidence or arguments for and against the validity and utility of dysfunctional beliefs. 4. Come to a reasoned conclusion by evaluating the evidence for and against. 5. Make behavioural changes that are consistent with the reasoned conclusion. 6. Develop believable disputing thoughts and more realistic interpretations. 7. Gradually modify underlying assumptions reflected by more specific beliefs. Adapted from Garner et al. (1997). Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 189 against a particular dysfunctional belief. Most of the following cognitive strategies have been described in connection with the treatment of other emotional disorders; however, the content and style have been adapted for eating disorders. Articulation of beliefs Normal verbalisation in therapy tends to be complex, fragmented, disjointed and often vague. Beliefs and dysfunctional thoughts are embedded in complicated accounts of current and past experiences. Even with some exposure to the cognitive model, patients require practice in thinking about thinking and help in distilling specific beliefs from their more complex stream of thought. Sometimes simplifying or consolidating a belief may make the distortion highly apparent and lead to immediate attitude change. Decentring Decentring involves the process of evaluating a particular belief from a different perspective in order to appraise its validity more objectively. It is particularly useful in combating egocentric interpretations that the patient is central to other people’s attention. For example, a patient reported “I can’t eat in front of others in the residence cafeteria because others will be watching me.” First, it needs to be established that the eating behaviour was not indeed unusual. If not, the therapist might enquire: “How much do you really think about others’ eating? Even if you are sensitised to their eating, how much do you really care about it except in the sense that it reflects back to your own eating? Even if your behaviour was unusual, do others really care?” Through the technique of decentring, the patient may be encouraged to develop a more realistic idea of the impact that most behaviour has on others. Challenging dichotomous reasoning Dichotomous reasoning (all-or-none or absolutistic thinking) is a common problem in anorexia nervosa. Beliefs that foods are either “good” and “bad”, that deviation from rigid dieting is equivalent to bingeing, and that gaining a pound is a sign of complete loss of control are all reflections of dichotomous reasoning. This style of thinking is applied to topics beyond food and weight. Patients commonly report extreme attitudes in the pursuit of sports, school, careers, and acceptance from others. This type of reasoning is particularly evident in the beliefs about self-control. Common examples include: “If I am not in complete control, I will lose all control; if I learn to enjoy sweets, I will not be able to restrain myself; if I stop exercising for one day, I will never exercise; if I enjoy sexual contact, I will become promiscuous; if I become angry, I will devastate others with my rage.” A major therapeutic task is to teach the 190 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch patient to recognise this style of thinking, to examine the evidence against it, to evaluate its maladaptive consequences, and to practise adopting a more balanced lifestyle. Decatastrophising Ellis (1962) originally described decatastrophising as a strategy for challenging anxiety that stems from magnifying negative outcomes. It involves the therapist asking the patient to clarify vague and implicit predictions of calamity by asking: “What if the feared situation did occur? Would it really be as devastating as imagined? How would you cope if the feared outcome does occur?” Ironically, catastrophising can actually produce the feared outcome. In an attempt to avoid social rejection and isolation, patients can withdraw from all social interactions, thus becoming isolated. Fear of failure can lead to the scrupulous avoidance of risk which results in failure. Moreover, there is no relief from catastrophic thinking. If a patient believes that weight gain would be a catastrophe, it is clear why they would be fearful and anxious when they gain weight. What is less obvious is the fact that they are usually anxious when they do not gain because they can never be completely free of the risk. In addition to helping the patient temper dire forecasts about the future, the therapist can facilitate the development of coping plans for mastering feared situations if they were to occur. Challenging beliefs through behavioural exercises A primary goal of cognitive therapy is helping patients alter behaviour by modifying dysfunctional beliefs and underlying assumptions. However, the reciprocal effect of behaviour on belief change is at least as important in the treatment of eating disorders. Anxiety and fear are central to the maintenance of eating disorder symptoms. Even the most careful cognitive preparation does not eliminate the fear associated with changed eating patterns and weight gain. At some point, if patients are to recover, they must begin making behavioural changes in these areas. Behavioural changes provide the real opportunity to probe, challenge and correct faulty assumptions regarding eating, weight and related self-attributions. It is difficult to maintain the belief that you cannot eat dietary fat or sugar without losing control, if you indeed consume these substances without binge-eating. Similarly, behavioural change can have a profound effect on beliefs unrelated to food and weight. Social interaction can attenuate the view of self as socially incompetent. Independent and self-reliant behaviour interferes with personal and family schemas that foster overprotectiveness and excessive dependence. However, it is common for well-established beliefs to remain intact, despite an undeniably contradictory behaviour. It is important for the therapist to make sure that the implications of the behavioural change are integrated at the cognitive level. Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 191 Reattribution techniques There are no reliable methods for directly modifying body size misperception in anorexia nervosa. Rather than correcting size misperception reported by some patients, it is useful to simply reframe the interpretation of the experience. This involves interrupting and overriding self-perceptions of fatness with higher-order interpretations such as “I know that those with anorexia nervosa cannot trust their own size perceptions” or “I expect to feel fat during my recovery, so I must consult the scale to get an accurate reading of my size.” The therapist asks the patient to attribute these body self-perceptions to the disorder and to refrain from acting upon intrusive thoughts, images or body experiences. This approach is contrary to the general therapeutic goal of encouraging self-trust in the validity and reliability of internal experiences. Modifying self-concept Self-concept is a broad and multidimensional construct involving at least two sub-components: self-esteem and self-awareness. Self-esteem constitutes the appraisal or evaluation of personal value, including attitudes, feelings, and perceptions. In contrast, self-awareness relates to the perception and understanding of the internal processes that guide experience. Vitousek and Ewald (1993) have organised self-concept deficits characteristic of anorexia nervosa into three broad clusters of variables: the unworthy self, the perfectible self and the overwhelmed self. The unworthy self is characterised by (1) low self-esteem, (2) feelings of helplessness, (3) a poorly developed sense of identity, (4) a tendency to seek external verification, (5) extreme sensitivity to criticism, and (6) conflicts over autonomy/dependence. The second cluster, the perfectible self, includes (1) perfectionism, (2) grandiosity, (3) asceticism, and 4) a “New Year’s resolution” cognitive style. The third cluster, the overwhelmed self, is characterised by (1) a preference for simplicity, (2) a preference for certainty, (3) a tendency to retreat from complex or intense social environments. Improving self-esteem It is well recognised that poor self-esteem often predates the appearance of eating disorder symptoms. The pride and accomplishment of weight control seem to temporarily alleviate this malady. The correction of low self-esteem, particularly if pervasive and long-standing, is a formidable task. At some point in therapy, patients usually reveal that they do not feel worthwhile or that they lack personal worth. This assumption may emerge in discussing the meaning of dieting and weight control as markers for constructs such as competence, control, attractiveness, and self-discipline which in turn reflect self-worth. It may be expressed in vague terms such as general feeling of ineffectiveness, helplessness or lack of inner direction. 192 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch It is useful for the therapist to help the patient distil vague assumptions about self-worth into a clear and simple statement such as “I feel like a failure”, “I do not feel like a worthwhile person” or “I must be liked by others in order to feel good about myself ”. Once the patient has expressed the view that she has low self-worth, it is useful to engage in a more general discussion about the basis for self-worth, later applying what has been learned back to particular index situations identified by the patient. It is often useful to begin by noting how much time and energy most people devote to trying to evaluate their self-worth. For most patients, weight or shape have become the predominant gauge for inferring self-worth. It is possible to determine the pros and cons of this frame of reference and then to extend this to other behaviours, traits or characteristics employed in the process of self-evaluation following the procedures described by Burns (1993). Decentring can be used to analyse this “balance-sheet” approach to human worth. Does the patient evaluate others in this same way? Is someone else considered worthless or inferior if she makes mistakes, is less intelligent, or does not perform well? The following example from Garner and Bemis (1985) illustrates the process: P: T: P: T: P: T: P: T: P: T: P: I am terrified I may do worse this year than last year in my studies. What would it mean if you did do worse? Well, I guess it would mean that I am not very good as a person. You mean you are rating your worth as a person by your grades? Yes, I guess that is right. It is important to do well in everything you attempt. I feel the same way about sports, hobbies, and my friends. In the last year losing weight has become the way for me to feel good about myself. The way that you are looking at your worth sort of relates to a philosophical question. How does one really evaluate or measure self-worth? [Operationalise belief.] You have implied that you base it on your daily performance, but this has some distinct disadvantages. [The therapist then outlines these as listed above.] Don’t all people judge their worth by what they do? We may do this to some degree, but not as literally or as harshly as you seem to do, and not on a moment-to-moment basis. In fact, you might ask yourself if you rate others’ worth by their performances. Do you rate your roommate’s worth based on her grades? You haven’t seemed particularly concerned about my grades in graduate school [decentering.] I just assumed that you did everything well. That is hardly the case. If you found that I did things poorly in several areas, would your evaluation of me decline? Well, no, but you are different. The aim of the approach is to help the patient gradually begin to question the utility of the “balance sheet” concept of self-worth. Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 193 Difficulties in labelling and expressing emotions Bruch (1962, 1973) considered the “lack of interoceptive awareness”, inability to accurately identify and respond to emotions and other internal sensations, as fundamental to anorexia nervosa. She observed that patients with anorexia nervosa “behave as if they had no independent rights, [and seem to believe] that neither their bodies nor their actions are self-directed, or not even their own” (p. 39). The failure to identify and respond accurately to internal sensations has received some empirical support (Bourke, Taylor, Parker, & Bagby, 1992; Schmidt, Jiwany, & Treasure, 1993). The confusion surrounding internal state extends to mistrust of the validity and reliability of attitudes, motives, and behaviour. The lack of confidence in thinking processes is reflected in exaggerated self-monitoring and rigidity. Cognitive theorists have attributed this tendency to idiosyncratic beliefs, assumptions or schemas that anorexia nervosa patients use in evaluating inner state (Garner & Bemis, 1985). These beliefs commonly centre around attitudes about the legitimacy, desirability, acceptability, or justification of inner experiences. The following comments by patients are clues to the operation of this process: “I do not know how I feel; how should I feel?; I do not experience pleasure; I never feel angry; I am always energetic and never get tired; I admire others who don’t show their feelings; I can’t stand these feelings – they are too strong; I don’t feel anything – I just binge.” Asked about feelings in a family interview, one patient appeared confused and responded by pointing to her mother stating: “Ask her, she knows me better than I do”. Similar mislabelling can be applied to other sensations like pleasure, relaxation or sexual feelings. Patients commonly interpret these sensations as “wrong”, frivolous or threatening. One patient reported: “If I give in to the urge to relax, I will become a degenerate.” Once distorted meanings are revised, it is important for the therapist to encourage behavioural exercises to reinforce and legitimise the new interpretations. Interpersonal focus in therapy Interpersonal concerns are inevitably expressed by anorexia nervosa patients during the protracted course of therapy. The prominence of interpersonal schemas has been the basis for their inclusion in earlier cognitive approaches to the disorder (Garner et al., 1982; Garner & Bemis, 1985; Guidano & Liotti, 1983). Fairburn (1993) has cautioned that combining cognitive behavioural and interpersonal therapy methods is “difficult, if not impossible, because their style and focus are so different” (p. 374) in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. He has suggested different pathways to explain the effectiveness of both forms of therapy in bulimia nervosa: 194 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch Cognitive Therapy ➔ Improved eating habits and attitudes ➔ Improved interpersonal functioning. Interpersonal Therapy ➔ Improved interpersonal functioning ➔ Improved eating habits and attitudes. Although there are stylistic differences in the two approaches, and it may be technically possible to exclude discussion of the interpersonal domain from cognitive therapy, the theoretical justification for this separation is not obvious. Self-schemas and interpersonal schemas both influence and are influenced by interactions with others. Although the interpersonal focus to therapy requires a shift in therapy content, the systematic reliance on standard cognitive procedures continues. Patients tend to apply the same types of schematic processing errors and dysfunctional assumptions to interpersonal relationships as those displayed in other areas. Cognitive therapy generally eschews the exploration of historical material; however, this approach can be therapeutic in examining interpersonal schemas. First, it is sometimes necessary to examine historical relationships to find recurrent interpersonal patterns. Second, it can be useful for patients to develop some understanding of the historical events and relationships that may have made particular interpersonal schemas “adaptive”. Understanding the earlier adaptive context can allow the patient to make sense of current dysfunctional interpersonal schemas. Therapy sessions provide in vivo opportunities to assess dysfunctional interpersonal schemas that may generalise outside of therapy. For example, the patient might be encouraged to examine beliefs that interfere with assertiveness and then practise assertiveness in the therapy session. The therapist and the patient then need to plan out-of-session opportunities to apply this newly acquired skill outside of the therapy session. Family therapy Support for involving the family in the treatment of eating disorders comes from a number of sources. First, there are ethical, financial and practical grounds for including the parents in the treatment of younger anorexia nervosa patients. Second, recovered patients consider resolution of family and interpersonal problems as pivotal to recovery (Hsu, Crisp, & Callender, 1992; Rorty, Yager, & Rossotto, 1993). Third, though early reports may have overstated the effectiveness of family therapy (Martin, 1983; Minuchin et al., 1978; Selvini-Palazzoli, 1974), this mode of intervention has had an enduring impact in the treatment of anorexia nervosa (Vandereycken, Kog, & Vanderlinden, 1989) and has received empirical support in controlled trials (Crisp, Norton, Gowers et al., 1991; Russell, Szmukler, Dare, & Eisler, 1987). Practical factors are sufficiently compelling to justify the family approach with some patients; however, our primary impetus for integrating family and Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 195 cognitive approaches to anorexia nervosa is the conceptual harmony that can be achieved in integrating these two treatment models (Garner et al., 1982, 1986). On a fundamental level, there is agreement between models that “meaning” is the primary locus of clinical concern. Also, both models assume symptoms are adaptive on one level of meaning and dysfunctional on another. Nevertheless, attempts to find common theoretical ground between cognitive and family therapy have revealed key differences as well as significant areas of overlap (Epstein, Schlesinger, & Dryden, 1988; Leslie, 1988). Some contrasts relate to intervention tactics and style while others pertain to the language and conceptualisation of the change process (Epstein et al., 1988). Epstein et al. (1988) define the role of the cognitive therapist as a consultant to clients who generate, accept or reject new cognitions based on rational evaluation of the evidence. This differs from the systems and structural therapist who provides new meaning to symptoms and prescribes behavioural change. However, the evolution of cognitive theory toward including different levels of meaning tends to blur these distinctions. The central question remains – how is family therapy conducted from a cognitive perspective? One issue that often bitterly divides the family and individual therapy camps may actually be illusory. It pertains to the mistaken assumption that family therapists rely exclusively on the family format for sessions. Although the point has not been widely publicised, Minuchin et al. (1978) recommended family therapy sessions only in the beginning for older adolescents, “moving quickly to separate the patient into individual sessions and the parents into marital sessions in order to foster disengagement” (p. 132). Family therapists argue that an eating disorder can maintain certain dysfunctional roles, alliances, conflicts or interactional patterns within the family. Eating symptoms may be functional by directing attention away from basic conflicts in the family. For example, eating symptoms may prevent parents from addressing serious marital discord. Whether the format is individual or family, the conceptual framework offered by systems theorists can be directly translated into terms consistent with modern cognitive theory. The cornerstone of systemic and structural family theory is the recognition that symptoms and behaviours function on different levels, adaptive at one level but maladaptive at another. In both cognitive and family therapy, the primary objective is to expose and alter meanings, generally by achieving shifts in interactional patterns. A premise of both orientations to family therapy is that an eating disorder can deflect members of the family away from the developmental tensions that naturally emerge with the transition to puberty and the attendant preparation for emancipation. In this case, the eating disorder serves as a maladaptive solution to the child’s struggle to achieve autonomy. Moves toward independence are perceived as a threat to family unity and activate behaviours aimed at preserving the status quo. This view is consistent with other major theories of anorexia nervosa including the 196 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch cognitive formulations we presented earlier. The only difference is the degree of emphasis on the individual’s versus the family’s reaction to this same predicament. The cognitive therapist does not assume the specific meaning behind interactional patterns, but tries to assist the patient and the family in identifying dysfunctional assumptions through questioning and the prescription of behavioural change. Some examples illustrate multi-level beliefs. One patient did not know why she was so angry at her mother’s cheerful and congenial manner until she realised that it was really insincere. This same patient communicated her anger in her conflict-avoidant family by vomiting, claiming that her behaviour was involuntary. The clue to the meaning of her behaviour was that she always left the bathroom door open and retched so that all could hear. By defining her vomiting as involuntary, she denied its hostile intent and avoided reprisals. Conclusion This chapter has provided a broad overview of the cognitive behavioural approach to the treatment of eating disorders. Specific components of treatment have been recommended such as self-monitoring, introduction of avoided foods, and normalising body weight where appropriate. Assumptions that typically become the focus of cognitive restructuring were reviewed, and a sampling of strategies for addressing these have been provided. One of the major benefits of CBT methods is that they are not necessarily incompatible with other models for understanding eating disorders. In light of the growing body of empirical support for the effectiveness of CBT methods in the treatment of bulimia nervosa, they should be considered the standard against which other methods are measured. The conclusions for the value of CBT treatment for anorexia nervosa must be tentative at present because there has been insufficient empirical research in which its efficacy has been systematically examined. Acknowledgement Portions of this chapter have been adapted with permission from: Garner, D.M., Vitousek, K., & Pike, K. (1997). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anorexia nervosa. Handbook of Treatment for Eating Disorders (pp. 94–144). D.M. Garner & P.E. Garfinkel (Eds.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. References Agras, W.S., Schneider, J.A., Arnow, B., Raeburn, S.D., & Telch, C.F. (1989). Cognitive-behavioral and response-prevention treatments for bulimia nervosa. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, 215–221. Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 197 American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Medical Association. Beck, A.T. (1976). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. New York: International Universities Press. Beck, A.T. & Emery, G. (1985). Anxiety Disorders and Phobias. A Cognitive Perspective. New York: Basic Books. Beck, A.T., Rush, A.J., Shaw, B.F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press. Bourke, M.P., Taylor, G.J., Parker, J.D.A., & Bagby, R.M. (1992). Alexithymia in women with anorexia nervosa – A preliminary investigation. British Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 240–243. Bruch, H. (1962). Perceptual and conceptual disturbances in anorexia nervosa. Psychosomatic Medicine, 24, 187–194. Bruch, H. (1973). Eating Disorders: Obesity, Anorexia Nervosa and the Person Within. New York: Basic Books. Burns, D.D. (1993). Ten Days to Self-Esteem. New York: Quill William Morrow. Casper, R.C. (1990). Personality features of women with good outcome from restricting anorexia nervosa. Psychosomatic Medicine, 52, 156–170. Crisp, A.H., Norton, K., Gowers, S., Halek, C., Bowyer, C., Yeldham, D., Levett, G., & Bhat, A. (1991). A controlled study of the effect of therapies aimed at adolescent and family psychopathology in anorexia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 325–333. Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. New York: Lyle Stuart. Epstein, N., Schlesinger, S.E., & Dryden, W. (1988). Concepts and methods of cognitivebehavioral family treatment. In N. Epstein, S.E. Schlesinger, & W. Dryden (Eds.), Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy With Families. New York: Brunner/Mazel Publishers. Fairburn, C.G. (1985). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for bulimia. In D.M. Garner & P.E. Garfinkel (Eds.), Handbook of Psychotherapy for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia. New York: Guilford Press. Fairburn, C.G. (1993). Interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. In G.L. Klerman & M.M. Weissman (Eds.), New Applications of Interpersonal Psychotherapy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Fairburn, C.G., Jones, R., Peveler, R.C., Carr, S.J., Solomon, R.A., O’Connor, M.E., Burton, J., & Hope, R.A. (1991). Three psychological treatments for bulimia nervosa: A comparative trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 463–469. Fairburn, C.G., Marcus, M.D., & Wilson, G.T. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating and bulimia nervosa. In C.G. Fairburn & G.T. Wilson (Eds.), Binge Eating. Nature: Assessment, and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press. Fairburn, C.G., Norman, P.A., Welch, S.L., O’Connor, M.E., Doll, H.A., & Peveler, R.C. (1995). A prospective study of outcome in bulimia nervosa and the long-term effects of three psychological treatments, Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 304–312. Garner, D.M. (1986). Cognitive therapy for anorexia nervosa. In K.D. Brownell and J.P. Foreyt (Eds.), Handbook of Eating Disorders. New York: Basic Books. Garner, D.M. (1988) Anorexia nervosa. In M. Hersen & C.G. Last (Eds.), Child Behavior Therapy Casebook, pp. 263–276. New York: Plenum Press. Garner, D.M. (1997). Psychoeducational principles in treatment. In D.M. Garner & P.E. Garfinkel (Eds.), Handbook of Treatment for Eating Disorders. New York/London: Guilford Press. 198 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch Garner, D.M. and Bemis, K.M. (1982). A cognitive-behavioral approach to anorexia nervosa. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6, 123–150. Garner, D.M. and Bemis, K.M. (1985). Cognitive therapy for anorexia nervosa. In D.M. Garner and P.E. Garfinkel (Eds.), Handbook of Psychotherapy for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia. New York: Guilford Press. Garner, D.M., Fairburn, C.G., & Davis, R. (1987). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of bulimia nervosa: A critical appraisal. Behavior Modification, 11, 398–431. Garner, D.M., Garfinkel, P.E., & Bemis, K.M. (1982). A multidimensional psychotherapy for anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 1, 3–46. Garner, D.M., Garfinkel, P.E., & Irvine, M.J. (1986). Integration and sequencing of treatment approaches for eating disorders. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 46, 67–75. Garner, D.M. & Isaacs, P. (1985). Psychological issues in the diagnosis and treatment of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. In R.E. Hales & J. Francis (Eds.), The Psychology of Eating Disorders. Psychiatric Update, Vol. IV, pp. 503–515. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Garner D.M. & Needleman L. (1997). Sequencing and integration of treatments. In D.M. Garner & P.E. Garfinkel (Eds.), Handbook of Treatment for Eating Disorders. New York/London: Guilford Press. Garner D.M., Olmsted, M.P., Davis, R., Rockert, W., Goldbloom, D., & Eagle, M. (1990). The association between bulimic symptoms and reported psychopathology. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 1–15. Garner, D.M., Rockert, W., Olmsted, M.P., Johnson, C.L., & Coscina, D.V. (1985). Psychoeducational principles in the treatment of bulimia and anorexia nervosa. In D.M. Garner and P.E. Garfinkel (Eds.), Handbook of Psychotherapy for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia. New York: Guilford Press. Garner, D.M., Rockert, W., Garner, M.V., Davis, R., Olmsted, M.P., & Eagle, M. (1993). Comparison of cognitive-behavioral and supportive-expressive therapy for bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 37–46. Garner, D.M. & Rosen, L.W. (1990). Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. In A.S. Bellack, M. Hersen and A.E. Kazdin (Eds.), International Handbook of Behavior Modification and Therapy, 2nd ed. New York: Plenum Publishing. Garner D.M., Vitousek K., & Pike K. (1997). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anorexia nervosa. In D.M. Garner & P.E. Garfinkel (Eds.), Handbook of Treatment for Eating Disorders. New York/London: Guilford Press. Garner, D.M. & Wooley, S.C. (1991). Confronting the failure of behavioral and dietary treatments for obesity. Clinical Psychology Review, 11, 729–780. Guidano, V.F. & Liotti, G. (1983). Cognitive Processes and Emotional Disorders: A Structural Approach to Psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Press. Hsu, L.K.G. (1988). The outcome of anorexia nervosa: A reappraisal. Psychological Medicine, 18, 807–812. Hsu, L.K.G., Crisp, A.H., & Callender, J.S. (1992). Recovery in anorexia nervosa – the patient’s perspective. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 11, 341–350. Leslie, L.A. (1988). Cognitive-behavioral and systems models of family therapy: How compatible are they? In N. Epstein, S.E. Schlesinger, & W. Dryden (Eds.), Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy With Families. New York: Brunner/Mazel Publishers. Martin, F. (1983). Subgroups in anorexia nervosa: A family systems study. In. P.L. Cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders 199 Darby, P.E. Garfinkel, D.M. Garner, & D.V. Coscina (Eds.), Anorexia Nervosa: Recent Developments. New York: Alan R. Liss. Minuchin, S., Rosman, B.L., & Baker, J. (1978). Psychosomatic Families: Anorexia Nervosa in Context. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Mitchell, J.E., Pomeroy, C., & Adson, D.E. (1997). Managing medical complications. In D.M. Garner & P.E. Garfinkel (Eds.), Handbook of Treatment for Eating Disorders. New York/London: Guilford Press. Olmsted, M.P., Davis, R., Garner, D.M., Eagle, M., & Rockert, W. (1991). Efficacy of brief psychoeducational intervention for bulimia nervosa. Behavior Research and Therapy, 29, 71–83. Pike, K.M., Loeb, K., & Vitousek, K. (1996). Cognive-behavioral therapy for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. In J.K. Thompson (Ed.), Body Image. Eating Disorders and Obesity. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Polivy, J., & Herman, C.P. (1985). Dieting and bingeing: A causal analysis. American Psychologist, 40, 193–201. Rorty, M., Yager, J., & Rossotto, E. (1993). Why and how do women recover from bulimia nervosa? The subject appraisals of forty women recovered for a year or more. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 14, 249–260. Rosen, J.C., & Leitenberg, H. (1985). Exposure plus response prevention treatment of bulimia. In D.M. Garner & P.E. Garfinkel (Ed.), Handbook of Psychotherapy for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia. New York: Guilford Press. Russell, G.F.M. (1970). Anorexia nervosa: Its identity as an illness and its treatment. In J.H. Price (Ed.), Modern Trends in Psychological Medicine, Vol. 2. London: Butterworths. Russell, G.F.M., Szmukler, G.I., Dare, C., & Eisler, I. (1987). An evaluation of family therapy in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 1047–1056. Schmidt, U., Jiwany, A., & Treasure, J. (1993). A controlled study of alexithymia in eating disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 1, 54–58. Selvini-Palazzoli, M.P. (1974), Self-starvation. London: Chaucer Publishing. Sharp, C.W., & Freeman, C.P.L. (1993). The medical complications of anorexia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 452–462. Teasdale, J.D., & Barnard, P. J. (1993). Affect, Cognition, and Change: Re-Modelling Depressive Thought. Hove (UK): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Vandereycken, W., Kog, E., & Vanderlinden, J. (1989). The Family Approach to Eating Disorders. New York: PMA Publishing Corp. Vitousek, K.B., & Ewald, L.S. (1993). Self-representation in eating disorders: A cognitive perspective. In Z. Segal & S. Blatt (Eds.), The Self in Emotional Disorders: Cognitive and Psychodynamic Perspectives. New York: Guilford Press. Vitousek, K.B., & Orimoto, L. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral models of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and obesity. In P. Kendal & K. Dobson (Eds.). Psychopathology and Cognition. New York: Academic Press. Walsh, B.T., Wilson, G.T., Loeb, K.L., Devlin, M.J., Pike, K.M., Roose, S.P., Fleiss, J., & Waternaux, C. (1997). Medication and psychotherapy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 523–531. Wilson, G.T., Eldredge, K.L., Smith, D., & Niles, B. (1991). Cognitive-behavioral treatment with and without response prevention for bulimia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 29, 575–583. 200 David M. Garner and M. Teresa Blanch Wilson, G.T., Fairburn, C.G., & Agras, W.S. (1997). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. In D.M. Garner & P.E. Garfinkel (Eds.), Handbook of Treatment for Eating Disorders. New York/London: Guilford Press. Wilson, G.T., Rossiter, E., Kleifield, E.I., & Lindholm, L. (1986). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of bulimia nervosa: A controlled evaluation. Behavior Research and Therapy, 24, 277–288. Chapter 8 Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders Jeffrey E. Young Introduction The emergence of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has led to new methods of treating patients with a character pathology or what DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 1997) refers to as personality disorders. As cognitive therapists have become more interested in examining core structures and the factors which affect personal growth negatively and positively, they have moved from treating only Axis I disorders like depression or anxiety to working with the more deep-seated characterological disorders of Axis II. Paralleling and influenced by the constructivist movement within cognitive therapy, Young has proposed an integrative model called schema-focused therapy (SFT), designed to extend rather than replace Beck’s original model and specifically address the needs of patients with long-standing characterological problems. The intention of this chapter is to describe the practical applications of schema-focused therapy against a background of its theoretical postulates. Historical roots of schema-focused therapy Cognitive therapy was developed as a movement away from the limitations of psychoanalysis and the restrictive nature of radical behaviourism (Dobson, 1988). Beck’s cognitive therapy derived directly from his efforts to test Freud’s theory that, at its core, depression is anger turned back on itself. Studying his depressed patients, Beck concluded that depression is characterised by a consistent bias towards negative interpretations of the self, the environment, and the future. Emotions were explained as the result of ongoing cognitive appraisals: distorted appraisals and the negative emotions which result from these distortions became the focus of the cognitive model. In contrast to the psychoanalytic model and the strict behavioural tradition, Beck proposed that dysfunctional beliefs could readily be brought into conscious awareness. He theorised that core assumptions about the self, the future, and the environment seem unconscious because of the same nonpathological mechanisms by which other habits of thinking and behaving 202 Jeffrey E. Young become automatic. He advocated active dialogue with patients through which he trained his patients to develop empirical, reality-based arguments to combat distortions in their thinking. Because the patient and the therapist work together as a team, systematically testing the patient’s thoughts and beliefs, this working style was called “collaborative empiricism”. One of the most widely researched of the psychotherapies, there is promising evidence that cognitive therapy may be superior to pharmacology and non-behavioural psychotherapies in preventing relapse (Dobson, 1989), and there is growing evidence that it is also effective for anxiety and other disorders. The questions of process and outcome are still being actively researched (Beckman & Watkins, 1989; Robins & Hayes, 1993). The clinical impact of cognitive therapy has been enormous. However, rather than a single integrated method, by 1990 more than twenty different types of cognitive therapy had been identified (Haaga & Davidson, 1991). Limitations of cognitive therapy and the constructivist movement Therapists working with personality disorders and other chronic problems found limitations in Beck’s original model. Young (1994a) proposed that several conditions had to be met for patients to succeed with Beck’s model: 1 2 3 4 5 that patients have ready access to their thoughts and feelings; that patients have identifiable life problems to focus on; that patients are able and willing to do homework assignments; that patients can engage in a collaborative relationship with the therapist; and that patients’ cognitions be flexible enough to be modified through established cognitive-behavioural procedures. Patients with personality disorders often do not meet these conditions, and, to the extent that they do not, Young discovered that the therapy with them would often fail without significant alterations. This thinking coincides with the constructivist movement within cognitive therapy. Several developments in psychology challenged many of the assumptions and intervention strategies of mainstream cognitive therapy (Mahoney, 1993). These include: new research findings on the nature of emotions, the incorporation of experiential techniques into clinical practice, the study of unconscious processes in cognitive therapy, an increasing focus on self-organising and self-protective processes in personality and life-span development, and social, biological, and embodiment processes in therapy. For constructivists, human cognition is seen as proactive and anticipatory rather than passive and determined. As a consequence, constructivists tend to challenge broader systems of personal constructs rather than disputing Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders 203 circumscribed units of thought (Neimeyer, 1993). Because these systems are believed to have enduring continuity over time, developmental dimensions of patients’ psychopathology are emphasised, with particular attention to primary attachment relationships. The goal of the constructivist therapist is creative rather than corrective. The interventions are likely to be reflective and intensely personal rather than analytic or technically instructive. Emotions are viewed as informative, reflecting patients’ attempts to construct meaning out of their experiences. Resistance is seen as self-protective when the therapist seems to threaten patients’ core ordering processes. The development of schema-focused therapy Faced with the problems of treating patients with long-standing characterological disorders, Young developed schema-focused therapy. Young (1994a) proposed that such patients have certain characteristics which make them unsuitable for standard cognitive therapy. He identified four important characteristics. Diffuse presentation Patients with characterological problems often lack the kind of readily identifiable problems which can become the focus of treatment. Such patients often exhibit significant disturbance in personal adjustment yet present vague, ill-defined, or generalised complaints. With no specific target, the standard techniques of cognitive therapy require modification. Interpersonal problems Interpersonal difficulties are emphasised in DSM-IV (APA, 1994) for Axis II patients and are often the core problem for these patients. In traditional cognitive therapy, patients are expected to engage in a collaborative relationship with the therapist in a few sessions. This may be difficult for some of these patients while others may become overly dependent on their therapist. If these difficulties are viewed as a barrier to the real tasks of therapy, the core problems may be missed. Rigidity In traditional cognitive therapy, patients are assumed to have a certain flexibility which enables them to modify their thoughts and behaviours through empirical analysis, logical discourse, experimentation, gradual steps, and practice. Because one of the hallmarks of personality disorders is the presence of rigid, inflexible traits, standard cognitive therapy techniques alone 204 Jeffrey E. Young may meet with limited or no success. Patients with entrenched patterns of thinking and behaving may not yield to months of therapeutic work; even those patients able to acknowledge their maladaptive thoughts or actions may still maintain a sense of hopelessness about changing their core feelings, behaviours, or beliefs. Avoidance Since patients with characterological problems chronically block or avoid painful feelings (affective avoidance; see Young, 1994a) and thoughts (cognitive avoidance), standard cognitive techniques are often unsuccessful in gaining access to their thoughts and feelings. Young theorises that this avoidance develops as a result of aversive conditioning: anxiety and depression become associated with memories and cognitions, leading to avoidance. Although patients with uncomplicated Axis I disorders also exhibit avoidance, they have relatively free access to their thoughts and feelings. For instance, patients with panic disorder may avoid looking at their catastrophic thoughts, but, with sufficient training, they generally are able to access their automatic thoughts, and thus challenge and modify their thoughts and behaviour. The schema-focused model: theoretical framework In the schema-focused model, four main constructs are proposed: early maladaptive schemas, schema processes, schema domains, and schema modes. This model is not intended as a comprehensive theory of psychopathology but rather as a working theory to guide clinical interventions with patients who present with character disorders and other chronic disorders. Early maladaptive schemas Schemas have been defined as “organized elements of past reactions and experience that form a relatively cohesive and persistent body of knowledge capable of guiding subsequent perceptions and appraisals” (Segal, 1988). Beck noted the importance of schemas in some of his earliest work. “On the basis of the matrix of schemas, the individual is able to orient himself in relation to time and space and to categorize and interpret his experiences in a meaningful way” (Beck, 1967). Rather than present a competing theory of schemas, Young (1994a) proposes a subset of schemas called “early maladaptive schemas (EMS)”. Instead of concentrating on automatic thoughts and underlying assumptions, the Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders 205 schema-focused approach proposes a primary emphasis on the deepest level of cognition, the early maladaptive schema1. The schema-focused model defines schemas as “broad, pervasive themes regarding oneself and one’s relationship with others, developed during childhood and elaborated throughout one’s lifetime” and dysfunctional to a significant degree (Young, 1994a). Schemas are essentially implicit, unconditional motifs held by individuals. They are perceived as irrefutable and are taken for granted. Schemas serve as a template for processing experience and, as a result, become elaborated throughout life and define an individual’s behaviours, thoughts, feelings, and relationships with other people. In contrast with underlying assumptions, schemas are usually unconditional and, therefore, far more rigid. Essentially, schemas are usually valid representations of the noxious experiences of childhood. The problem is that schemas over time become deeply entrenched patterns of distorted thinking and dysfunctional behaviour. Because schemas develop early in life, they become habitual and unquestioned, often defining selfconcepts and views of our world. Even when presented with evidence that refutes the schema, many individuals distort information to confirm the validity of the schema. By definition, schemas are significantly dysfunctional. They interfere with the individual’s ability to satisfy basic needs for stability and connection, autonomy, desirability, and self-expression, or the capacity to accept reasonable limits. The threat of schematic change is too disruptive to the core organisation to be tolerated and, hence, a variety of cognitive and behavioural manœuvres arise that ultimately reinforce the schema. These are called schema processes. Schema processes Three schema processes are proposed: maintenance, avoidance, and compensation. These are automatic processes which overlap with the psychoanalytic concepts of resistance and defence mechanisms. They are maladaptive styles of coping used by the individual that are activated by and, in turn, reinforce the schemas. Schema maintenance Schema maintenance refers to cognitive distortions and maladaptive behaviour that directly reinforce and perpetuate a schema. For instance, individuals with defectiveness schemas may settle for a menial job rather than seek one that will demonstrate their gifts. 1 The term “schema” will be used to refer to “early maladaptive schemas” in this paper. 206 Jeffrey E. Young Schema avoidance Schema avoidance refers to the cognitive, behavioural, and emotional strategies by which the individual attempts to avoid triggering a schema and the inherent intense affect. This involves distracting oneself from thinking about schema-connected issues or avoiding situations likely to trigger them. For example, a patient with the Failure schema may avoid working on a project because he fears it will be poorly evaluated; by doing so, he makes it likely that he will obtain a negative evaluation, thus further reinforcing the schema. Schema compensation Schema compensation refers to behaviours or cognitions which overcompensate for a schema; they appear to be the opposite of what one would expect from a knowledge of patients’ early schemas. Schema compensation represents early functional attempts of the child to redress and cope with the pain of mistreatment by parents, siblings, and peers. However, schema compensations are often too extreme for an adult environment and ultimately backfire, serving to reinforce the schema. An individual with the Emotional Deprivation schema may demand too much of others, alienating them and thus feeling even more deprived. Schema domains and developmental origins Young has identified eighteen schemas and has outlined specific cognitive, behavioural, and interpersonal strategies for treatment of each schema (Bricker, Young, & Flanagan, 1993; Young, 1994a). Each schema is grouped in one of five broad categories or domains, and each domain is believed to interfere with a core need of childhood. This section provides a description of each schema domain. A list of domains and schemas is presented in Table 8.12. Disconnection and Rejection Patients with these schemas expect that their needs for security, stability, nurturance, empathy, sharing of feelings, acceptance, and respect will not be met in a predictable manner. Schemas in this domain (Abandonment/Instability, 2 This listing is tentative and constantly open to modification and elaboration based on our growing work within this model. Recent studies generally confirm the factor structure of the Schema Questionnaire, a self-report questionnaire derived through clinical experience and designed to assess the early maladaptive schemas (Young & Brown, 1994; Schmidt, Joiner, Young, & Telch, 1995; Schmidt, 1994). Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders 207 Mistrust/Abuse, Emotional Deprivation, Defectiveness/Shame, and Social Isolation/Alienation) typically result from a detached, cold, rejecting, withholding, lonely, explosive, or abusive family environment. Impaired Autonomy and Performance Patients with these schemas (Dependence/Incompetence, Vulnerability to Danger, Enmeshment/Undeveloped Self, and Failure) have expectations about themselves and the environment that interfere with their perceived ability to separate, survive, function independently, or perform successfully. The typical family in this schema domain is enmeshed, undermining of the child’s confidence, overprotective, or may fail to reinforce the child for performing competently outside the family. Impaired Limits Schemas within this domain (Entitlement/Grandiosity, Insufficient SelfControl/Self-Discipline) pertain to deficiency in internal limits, responsibility to others, or long-term goal orientation. These schemas lead to difficulty respecting the rights of others, cooperating, keeping commitments, or setting and meeting realistic personal goals. Patients with these schemas typically have families characterised by permissiveness, indulgence, a lack of direction, or a sense of superiority, rather than appropriate confrontation, discipline, and limits. In some cases the child may not have been pushed to tolerate normal levels of discomfort or may not have been given adequate supervision, direction, or guidance. Other-Directedness Within this domain, there is an excessive focus on the desires, feelings, and approval of others at the expense of one’s own needs, in order to gain love and approval, maintain one’s sense of connection, or avoid retaliation. Patients with these schemas (Subjugation, Self-Sacrifice, and ApprovalSeeking/Recognition-Seeking) often suppress or lack awareness of their own anger and natural inclinations. Typical of the family origin for these patients is conditional acceptance; children need to suppress important aspects of themselves to gain love, attention, and approval. Overvigilance and Inhibition Schemas within this domain include Negativity/Vulnerability to Error, Overcontrol/Emotional Inhibition, Unrelenting Standards/Hypercriticalness, and Punitiveness. Within this domain there is an excessive emphasis on controlling one’s spontaneous feelings, impulses, and choices in order to avoid 208 Jeffrey E. Young Table 8.1 Schema domains Domain I. Disconnection and Rejection Abandonment/Instability Mistrust/Abuse Emotional Deprivation Defectiveness/Shame Social Isolation/Alienation Domain II. Impaired Autonomy and Performance Dependence/Incompetence Vulnerability to Danger Enmeshment/Undeveloped Self Failure Domain III. Impaired Limits Entitlement/Grandiosity Insufficient Self-Control/Self-Discipline Domain IV. Other-Directedness Subjugation Self-Sacrifice Approval-Seeking/Recognition-Seeking Domain V. Overvigilance and Inhibition Negativity/Vulnerability to Error Overcontrol/Emotional Inhibition Unrelenting Standards/Hypercriticalness Punitiveness making mistakes; or on meeting rigid, internalised rules about performance and ethical behaviour, often at the expense of happiness, self-expression, relaxation, close relationships, or health. The typical family origin tends to be grim and sometimes punitive: performance, duty, perfectionism, following the rules, and avoiding mistakes predominate over pleasure, joy, and relaxation. There is usually an undercurrent of pessimism and worry that things may fall apart if one fails to be vigilant at all times. Schema modes Young defines a schema mode as “a facet of the self, involving a natural grouping of schemas and schemas processes, that are not integrated with other facets” (Young & Flanagan, 1994). Although more than one schema may underlie an individual’s behaviour, all the schemas may not be active at the same time. Some schemas may be triggered while others remain dormant. Patients with severe characterological problems, such as those with borderline personality disorder, abruptly flip from one mode to another, Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders 209 primarily in response to life events or environmental circumstances. These schema modes are more or less cut off from each other, and patients may display different behaviours, cognitions, and emotions in each mode. Schema modes are different from personality traits in that they are coping mechanisms which are triggered by schematic events and correspond to “ego states” in psychoanalysis. Many patients understand schema modes more easily than they do the schemas that trigger them, and thus they may recognise the actions of the schema more comfortably. The principal modes are (Young & First, 1996): Child modes 1 Vulnerable Child 2 Angry Child 3 Impulsive/Undisciplined Child 4 Happy Child Maladaptive coping modes 5 Compliant Surrender 6 Detached Protector 7 Overcompensator 8 Punitive Parent Modes 9 Demanding Parent Healthy adult mode 10 Healthy Adult Clinicians must not only distinguish between the different modes, they must also be alert to triggers which activate each mode and note the different cognitions, emotions, and behaviours displayed by the patient in each schema mode. Practical applications of schema-focused therapy Schema-focused therapy is divided into two distinct phases: assessment and change. The assessment phase focuses on the identification and activation of the particular schemas which are most relevant for each patient. The change phase attempts to modify the relevant schemas by altering the distorted view of the self and others. SFT is an integrated therapy, using techniques from experiential and gestalt methods and object relations models as well as from the strictly cognitive behavioural model. It is also both objective and subjective, focusing on both the rational and the emotional. While it is useful to the practitioner to conceptualise assessment and change as distinct processes, in fact they may often overlap. Many patients find the venting which can take place during assessment therapeutic, while 210 Jeffrey E. Young therapists continue to assess in the change phase even while they may be empathising with the distress which the patient is expressing. Assessment The assessment phase entails several components. In schema identification, relevant schemas are identified via clinical analysis of the presenting problems and a life review, using inventories such as Young Schema Questionnaire (YSQ), the Multimodal Life History (MLH), the Young Parenting Inventory (YPI), the Young Compensation Inventory (YCI), and the Young–Rygh Avoidance Inventory (YRAI). The therapist also carefully observes the patterns in the therapy relationship. The Schema Grid (Young, 1990) helps the therapist view the relative power of the patient’s schemas. This form uses a count of the high scores on the Young Schema Index to make a sort of graph which illuminates the relationship of the various schemas. In schema activation, the therapist triggers identified schemas and affect through role-playing, dialogues, and imagery in order to confirm the role of the schemas and to overcome affective avoidance. In schema conceptualisation, to prepare for the change phase, the therapist develops a treatment plan with an overall conceptualisation of the relevant schemas. In schema education, the therapist discusses the conceptualisation of the problem in schema terms with the patient and they agree on a plan for change. These components are expanded below. Schema identification The first task of the schema-focused therapist is to identify the patient’s relevant schemas. This begins with an interview, as the patient describes the presenting problems. The therapist derives supporting information from other sources. The Young Schema Questionnaire (Young & Brown, 1994) is a 205item inventory that consists of a series of self-statements related to each EMS. The Multimodal Life History Inventory (Lazarus & Lazarus, 1991) is a record of important historical events in the patient’s life which helps the clinician generate hypotheses about schema origins and life patterns. The Young Parenting Inventory (Young, 1994b) illuminates the origin of schemas by asking clients to rate their parents separately on many statements regarding their childhoods (e.g., “criticised me a lot, spoiled me,” or “was overindulgent, in many respects”). This inventory can also be very helpful with patients who are out of touch with or avoidant of their feelings. Often the therapist is able to infer from the information provided by the questionnaire what the feelings probably are that the patient is avoiding. The Young Compensation Inventory taps into the degree and type of compensation. The Young–Rygh Avoidance Inventory measures the degree and type of schema avoidance. Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders 211 Once specific EMS are identified, the clinician must explore how the patient characteristically maintains, avoids, or compensates for the schemas. For example, a patient with a defectiveness schema may enter into a relationship with someone who is overly critical and thereby may come to feel even more defective. Identifying these schema processes helps the clinician determine how the patient perpetuates the schema while also providing important information about the primacy of certain schemas over others. Finally the therapist identifies the most relevant schema modes at this time. Schema activation As part of the assessment process, the therapist focuses on activating the primary schemas. One of the most valuable methods involves the use of experiential techniques, such as asking the patient to image early childhood scenes that come to mind, first with the mother, then with the father, and finally with any other significant adults or siblings from childhood. The purpose is to trigger affect associated with the identified schemas. The goal is two-fold. First, activating schemas during assessment confirms the primacy of identified schemas. That is to say that those schemas which elicit high levels of affect during schema activation sessions are usually considered primary while those that do not elicit such strong affect may be considered secondary for the patient. As mentioned earlier, patients with characterological disorders exhibit tremendous affective, cognitive, and behavioural avoidance. As long as a patient continues to avoid the thoughts and memories that cause painful emotions, keeping vital information out of awareness, therapy cannot proceed efficiently. Activating EMS enables such patients to tolerate painful feelings without withdrawing so that the change process may proceed effectively. The clinician also uses schema activation to overcome schema avoidance. This process is not intended to modify the schemas but merely to facilitate modification during the change phase. In essence, the role of the therapist is to help the patient tolerate low levels of schema-related affect and then gradually intensify the experience until the patient is able to tolerate the full imagery exercise without retreating from the image. This ultimately enables the patient to gain access to previously avoided thoughts and emotions which facilitates the modification of the underlying schemas during the change phase. Before the change phase can begin, the therapist must organise the material obtained during the assessment phase. It may require several sessions to get to this point, depending on the complexity of the issues involved and how wounded, self-protective, or avoidant the patient is. Two patients with the core schema of Defectiveness may exhibit vastly different clinical pictures. As well as being different in age, intelligence, ethnicity, talents, and so on, one patient with Defectiveness may come across as flamboyant, self-absorbed, and eager to talk 212 Jeffrey E. Young about superficial aspects of himself while another might be very guarded, shy, and threatened by any personal question, no matter how gently posed. The tool that finally integrates the information into a road map is the Schema Conceptualization Form (Young, 1992). This form guides the therapist through the complicated process of viewing the patient’s problem in schema terms and helps form an effective treatment plan so that there is a clear direction during the ensuing change phase. The form lists the schemas involved, the presenting problems with the schemas’ links, and schema triggers. It also looks at core memories, cognitive distortions, maintenance behaviours, avoidance strategies, and compensatory strategies. Then, taking into account the therapeutic relationship, the therapist lists the strategy for change linked to the problems at hand. Hence the conceptualisation is always tailored to the individual patient because the patterning of schemas and the particular way they interact is unique to each individual. Schema education Finally, before change is initiated, it is essential to explain the nature of EMS, domains, process, and modes to the patient in order to develop a shared understanding of the problems and core issues involved. This allows the patient and the therapist to agree on a conceptualisation of the problem and a treatment plan in the context of the schema model. To further consolidate their understanding of schemas, the therapist routinely recommends that patients read Reinventing Your Life (Young & Klosko, 1993), a self-help book based on the schema-focused approach. The change phase As stated earlier, the schema-focused model is an integrative approach to the treatment of patients with characterological disorders and incorporates experiential and interpersonal techniques within a cognitive behavioural framework. Since many of the cognitive and behavioural strategies used are similar to the ones used in standard cognitive therapy, this chapter will focus on techniques specific to this model. Cognitive techniques The overall aim of cognitive techniques is to alter the distorted view of the self and others which stem from the schema by presenting contrary objective evidence to refute it. Cognitive exercises are intended to improve the way patients habitually process information. Cognitive exercises include the “life review”, where patients are asked to provide evidence from their lives that supports or contradicts the schema. The goal of the life review is (a) to help the patient appreciate how their schemas Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders 213 distort their perceptions and feelings, thereby rigidly maintaining the schema and (b) to begin the process of distancing from, rather than identifying, with the schema. The Schema Therapy FlashCard (Young, 1996) is a form which replaces index cards on which the therapist can summarise and incorporate the most powerful evidence and counter-arguments against the patient’s schemas. This form is a four-step guide to be used in fighting schemas when they arise in everyday situations. The patient is urged to carry the flashcards and to review them frequently to continue the distancing process from the schema outside therapy. Furthermore the Schema Diary (Young, 1994c) helps the patient to view the role that schemas play in life in general and allows patients to understand what it is possible for them to do about them. Patients use these forms when feeling negative emotions. The therapist encourages patients to carry these tools wherever they may go and to read them repeatedly, especially when schemas are triggered (that is when there is a “schema attack”). The constant repetition of rational responses and the acknowledgement of evidence contrary to the schema at the time of its activation helps patients to gain distance from the schema and its related feelings as well as to identify increasingly with the newer, healthier, and more objective voice. Experiential techniques Experiential techniques have been increasingly incorporated into cognitive therapy in recent years (Daldrup, Beutler, Engle, & Greenberg, 1988; Safran & Segal, 1990) and are utilised to bring the patient’s emotions in sync with cognitive changes. These techniques appear to be among the most useful of all strategies in schema-focused therapy and appear to change the underlying schemas in a fundamental way that is usually more powerful than cognitive techniques alone. Experiential techniques enable the patient to experience the affective arousal associated with the schema. Among the two most commonly used experiential techniques are imagery and schema dialogues. SCHEMA DIALOGUE In a schema dialogue, the patient learns to reject the feelings elicited by the schema and to strengthen the healthy side of themselves. The therapist helps the patient to confront the schema by providing contradictory evidence to refute it. Just as the life review enables the patient to experience cognitive distance from the schema, the schema dialogue helps the patient to learn to fight the schemas and can promote freedom and self-efficacy. This technique requires two chairs so the patients can move back and forth between one and the other as they assume different personae. One chair is for 214 Jeffrey E. Young the schema; the other one is the healthy, rational voice. Generally, the patient has little or no trouble giving the schema its “voice”; the difficult part is usually finding the voice of the emerging healthy side as the schema is often so deeply embedded and accepted. The therapist may need to coach the healthy side; in the beginning patients may have little spontaneous material to refute the schema when they hold strongly felt negative beliefs. A variation of this technique is to have the patient pretend to confront a person who has played a particularly difficult role in his or her life. Again the patient is often adept at playing the detractor; the difficulty for the patient usually arises in finding the words for the refutation mode. Again coaching is often necessary. Also it can be useful to have the healthy schema mode challenge one of the maladaptive schema modes. In this case one chair represents the maladaptive mode while the other is the healthy mode, the patient moving back and forth between the two. With sufficient practice, patients gradually learn to assume the role of the healthy voice and almost automatically contradict the voice of the schema. When a patient gets to this stage, the ability to ventilate feelings and to reject the schemas provides a sense of liberation from this habitual way of thinking and facilitates a newer, healthier way of thinking and feeling. Many patients feel that studying the negative role is almost as helpful as learning the healthy role as the negative voice becomes more clearly identified as something extraneous. This demonstrates that the schema voice is not a valid one but only a maladaptive remnant of childhood. IMAGERY TECHNIQUES Imagery techniques are among the most powerful approaches to changing schemas. Whereas in the assessment phase patients focus on recalling and tolerating the pain and discomfort of schemas, working in the change phase, the therapist encourages the patient to recall an image from real life and to modify the image by acting in a more functional manner. The patient is asked to visualise the scene as vividly as possible. To this end, the therapist may ask patients to describe explicit details of the painful situation, such as how they looked at that age, the clothes they were wearing, how parents, siblings, or peers appeared, what the scene looked like, the time of day, and other such minutiae. During the imagery procedure, particular attention is paid to assessing feelings and thoughts relevant to the visualised scene. Patients are encouraged to stay with their feelings and ultimately to respond to the image with the newer, healthier pictures of themselves. For instance, during an imagery exercise, a female patient with the Defectiveness schema may be encouraged to express to her critical father how he made her feel and to defend herself. If this proves too difficult, the therapist may ask the patient’s permission to enter the image to help in the confrontation and provide a feeling of protection. Confronting the critical father in Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders 215 imagery may enable a patient to recognise the parent’s role in forming her Defectiveness schema, instead of attributing all the criticism to herself. Guided imagery can help patients to visualise a different experience from that which they knew; this can show that a different interpretation, or even a different experience, is possible. This again can weaken the power of the schema. Interpersonal techniques Since many patients with characterological disorders have difficulty establishing a therapeutic relationship, and since interpersonal problems are often the presenting problem for these patients, the therapeutic relationship is often a potent vehicle for schema modification. When patients who feel lonely and isolated or ones who feel mistrustful come to rely on the therapist, there is a powerful leverage for change. For instance, when patients with the Unrelenting Standards schema find the therapist accepting and empathic, they may begin to relent on their perfectionism. LIMITED REPARENTING One can construe one aspect of the therapist’s task as “limited reparenting” where the therapist attempts to provide a therapeutic relationship that counteracts the schemas. The patient’s schemas and schema domains guide the therapist in deciding what aspects of the reparenting process might be especially important. Limited reparenting is most valuable for patients with schemas in the Disconnection and Rejection domain, particularly those who experienced extreme criticism, abuse, instability, deprivation, or rejection as children. For example, if a patient’s parents were extremely critical, the therapist attempts to be as accepting as possible. The therapist might make a point of praising the patient and helping to recast events in a positive light. If the patient’s parents were withholding, the therapist attempts to be as nurturing as possible. The therapist can empathise with the painful experiences in the patients’ lives. Besides the general attitude of concern, the therapist’s supporting role within the images when that is appropriate and his or her support during the patient’s crises can give the patient the feeling of having a substitute or proxy parent. A young man with the Deprivation Schema who had feelings of hopelessness about finding a decent job and organising his life imaged the overwhelming difficulty he had had with homework in the home of his demanding but neglectful parents. He allowed the therapist to enter the image and help him with his assignment. The young man felt more optimistic and empowered. Of course, the therapist offers only an approximation of the missed emotional experience, maintaining the ethical and professional boundaries of the therapeutic relationship. No attempt is made to re-enact being the parent nor to regress the patient to a state of childlike dependency. 216 Jeffrey E. Young SCHEMAS TRIGGERED WITHIN THE THERAPY RELATIONSHIP Patients’ thoughts and feelings about the therapist also become relevant material in identifying, triggering, and modifying schemas. It is important to make the patient as comfortable as possible in discussing any feelings, especially negative feelings, about the therapist. Contrary to traditional psychoanalytic practice, the schema-focused therapist works collaboratively, directly, and openly with patients to identify the schema and the schema triggers when they arise during session. When a schema seems to be activated in relation to the therapist, the therapist gives patients the opportunity to test the validity of their beliefs. This can involve self-disclosure on the therapist’s part to correct a patient’s distortions. Often the therapist offers direct feedback that contradicts the patient’s schemadriven beliefs and expectations, and provides the patient with the opportunity to express highly charged feelings directly in session. Through repeated empathic confrontation – that is, contradicting patients’ negative ideas in an empathic and accepting manner which does not denigrate the patient – patients are taught to understand the role of the schemas in maintaining thoughts and expectations and to challenge and modify them as they arise during sessions. On the other hand, when the therapist has indeed done something which hurts or displeases the patient no matter how inadvertently, it is often helpful for the therapist to admit it. This can make the bond stronger. INTERPERSONAL RELATIONS Schemas are also maintained by patients’ current interpersonal environment, including intimate partners, friendships, and work. Patients gradually are made aware of their role in their schemas in affecting interpersonal relationships. Patterns that rise within the therapeutic relationship may also be true of interpersonal relationships in the patients’ life experience. At times, it may be helpful to invite those close to the patients like partners or friends to a session to help a patient assess the validity of the schemas and to modify dysfunctional relationships. During these sessions, the therapist identifies the patient’s schema-driven thoughts and expectations and helps the patient to draw accurate inferences about others. Such sessions also enable patients to communicate their previously unexpressed thoughts and feelings in a safe environment. The results of such meetings can often be dramatic, particularly when the participants can see how their schemas interact to produce conflict and disappointment. A woman with a Mistrust/Abuse schema can come to understand that her partner is devoted and that his occasional exasperation with her is not an excuse to desert her but only the normal friction of married life. Or, contrariwise, partners may be able to see where behaviour they see as normal may be hurtful to the patient. Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders 217 Behavioural techniques Behavioural techniques are used in schema-focused therapy to modify selfdefeating patterns of behavioural avoidance, maintenance, and compensation that perpetuate the patient’s schema. Although cognitive exercises weaken the schema, schematic thoughts may still be triggered in specific situations, causing the patient to continue to behave in ways that reinforce the schema. Therefore, the therapist uses behavioural exercises in conjunction with cognitive exercises to further challenge thoughts and behaviours. When appropriate, schema-focused therapy incorporates many well-established behavioural and operant techniques such as systematic exposure, teaching social skills, assertiveness training, and behavioural training to change behaviours that reinforce the schema. PERFORMING NEW BEHAVIOURS Sometimes the patient and the therapist jointly construct an exposure hierarchy to enable the patient to challenge the maladaptive thoughts systematically and to acquire and perform new behaviours which contradict the schema. Before in vivo exposure takes place, the patient rehearses each step in the hierarchy during the therapy session. This can be done by role playing or with guided imagery or both. This process reduces anxiety and increases the likelihood of success in the real life situation. This is because the patient will see these new behaviours as more familiar than if they were to try them “cold”. In fact, once patients have successfully completed each step in imaging, they are required to perform it outside the session (in vivo exposure). If patients perform the exercise successfully outside the session, they are reinforced during the next session. The therapist then guides the patient through the next, more difficult exercise in the hierarchy. A woman who feared panic attacks while driving in the city started by imaging driving on quiet streets with the therapist at her side. As she came to accept such images, the scene little by little included more threatening situations. Eventually patient and therapist used an actual automobile and finally the patient was able to drive the circumference of the city without difficulty. If the patient is unsuccessful, the situation is discussed at length during the next session to pinpoint exactly how and where it failed. The patient has a chance to discuss the event and vent any feelings about it. Once the source of the failure is identified, the appropriate exercises are rehearsed again during session before the patient attempts it again outside therapy. Often flashcards are helpful in fighting schemas in these circumstances. 218 Jeffrey E. Young BEHAVIOURAL PATTERN-BREAKING In addition to exercises that focus on adding new behaviours to their repertoire, patients are encouraged to stop behaving in ways that reinforce the schema. For example, since patients with the Defectiveness schema often perceive well-intentioned suggestions or casual remarks as harsh criticism (schema maintenance), they may be helped to distinguish useful suggestions from derogatory criticism. Once they are able to make this distinction, they are taught to confront partners who are inappropriately critical and terminate the relationship if the partner does not change. They might also learn to respond more appropriately to friends who offer feedback instead of becoming defensive or depressed. Likewise, if patients have the Subjugation schema and have an exploitative employer, they might consider finding employment with someone who treats the staff with respect. There can be similar strategies for most of the other schemas, depending on the patient’s situation. Homework Homework is very helpful in fighting schemas. It keeps the work present in the patient’s mind and helps to focus during the week on what has been accomplished during session. There are many possible kinds of homework. We have already discussed the life review. It is sometimes helpful to assign reading as, for instance, Reinventing Your Life. The patient may write a rebuttal to some schematic thought which emerged during session. The assignment of homework can often be a challenge to the therapist as ideally each assignment is tailor-made to the peculiar needs of that particular patient. This can tax the resourcefulness of the therapist, but the rewards in patient improvement can more than repay any effort in that direction. Commonly the therapist will ask the patient to list supposedly defective traits, following each in the next column with confirming evidence, and finally filling in a column with evidence that contradicts the schematic thought. The patient and the therapist go over this in the next session. Generally, in the beginning, the patient has difficulty with the contradicting evidence and needs considerable coaching from the therapist. A woman who has earned an MFA (Master of Fine Arts) and holds a highly responsible, well paying job saw herself as “lazy”. As she had come from a deprived blue collar background in which few of her relatives had even graduated from high school, the therapist was finally able to convince her that the idea that she was lazy came from some judgemental adults, family and teachers who helped bring her up. A lazy person could never have accomplished all that she had. Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders 219 Difficult cases Patients with borderline personality disorder may switch between four modes: the Detached Protector, the Vulnerable Child, the Angry Child, and the Punitive Parent. The Detached Protector is the default mode for most of these patients, and it serves to detach them from people and from the pain of experiencing emotions. Patients with borderline personality disorder usually experience a sense of depersonalisation, emptiness, or boredom and may appear excessively obedient or compliant. Substance abuse, bingeing, selfmutilation, and psychosomatic complaints are characteristic of this mode. Such patients may flip into the Abandoned Child mode if they feel threatened by fears of harm or abandonment. They then experience intense depression, hopelessness, fear, worthlessness, unloveability, victimisation, and great neediness. They may engage in frantic efforts to avoid abandonment and may even attempt suicide. A shift to the Punitive Parent mode, when patients with borderline personality disorder believe they have done something wrong (for example, having “inappropriate” feelings like anger), makes them begin to experience self-hatred and self-directed anger and they tend to punish themselves harshly for making mistakes. In severe cases they may even cut or mutilate themselves. The Detached Protector and Abandoned Child modes create tremendous anger in these patients because they involve the suppression of intense needs and feelings. When anger builds up to a point when it can no longer be contained, these individuals flip into the Angry Child mode. Their previously pent-up emotions are unleashed, and they often become enraged, demanding, devaluing, manipulative, controlling, and abusive. They now become focused on getting their needs met, but they do so in destructive ways – they become impulsive, make suicide attempts, engage in pent-up rage and acting out, and so forth. A patient with narcissistic personality disorder may often flip between three modes, the Special Self, the Deprived Child, and the Self Soother. Many narcissists spend the majority of their time in the Special Self mode, which comprises the Entitlement, Approval Seeking, Unrelenting Standards, and Mistrust schemas. In this mode they act superior, status oriented, entitled, and critical of others, showing little empathy. They may flip to the Deprived Child mode – comprising the Defectiveness, Emotional Deprivation, and Subjugation schemas – if they are cut off from sources of approval and validation when, for instance, they receive criticism. In this mode these individuals experience acutely the loss of special status and feel devalued. Finally, to escape the pain of being average, narcissists either switch back to the Special Self, or, failing attempts to regain approval and validation, they switch into a third mode, the Self Soother. This mode is a form of schema avoidance; its purpose is to distract or numb themselves from the pain of the Emotional Deprivation or the Defectiveness schemas. Self soothing can take 220 Jeffrey E. Young many forms, including drug and alcohol abuse, compulsive sexual activity, stimulation seeking – high stakes gambling or investing – overeating, extravagance, fantasies of grandiosity, and workaholism. As schema modes or facets of the self are more or less cut off from one another, and characterological patients display different cognitions, behaviours, and emotions in each one, the therapist must use different treatment strategies in response to each mode. The therapeutic goal is to integrate the different facets of the self by making the transition from one mode to another a seamless process. Clinical and empirical validation of schemafocused therapy In our clinical experience, Young’s schema-focused model has been successfully applied to patients with a range of DSM-IV disorders including prevention of relapse in depression and anxiety disorders (Young, Beck, & Weinberger, 1993); avoidant, dependent, compulsive, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders; substance abuse during the recovery phase; and to patients with a history of eating disorders, chronic pain, or childhood abuse (McGinn, Young, & Sanderson, 1995). However, controlled clinical outcome studies comparing the relative efficacy of schema-focused therapy versus standard cognitive therapy for the treatment of these disorders have yet to be conducted. Conclusion Schema-focused therapy is a promising new integrative model of treatment for a wide selection of lifelong patterns. It was proposed to meet the needs of patients with personality disorders who did not benefit fully from Beck’s early model of cognitive therapy. Schema-focused therapy adapts techniques used in traditional cognitive therapy but goes beyond the short-term approach by combining interpersonal and experiential techniques within a cognitive behavioural framework, utilising the concept of the early maladaptive schema as the unifying element. References American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition). Washington, DC: Author. Beck, A.T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, Experimental, and Theoretical Aspects. New York: Harper & Row. Beckman, E.E. & Watkins, J.T. (1989). Process and outcome in cognitive therapy. In A. Freeman, K. Simon, L. Buetler, & H. Arkowitz (Eds.), Comprehensive Handbook of Cognitive Therapy. New York: Plenum Press Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders 221 Bricker, D.C., Young, J.E., & Flanagan, C.M. (1993). Schema-focused cognitive therapy: A comprehensive framework for characterological problems. In K.T. Kuehlwein & H. Rosen (Eds.), Cognitive Therapies in Action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Daldrup, R.J., Beutler, L.E., Engle, D., & Greenberg, L.S. (1998). Focused Expressive Psychotherapy: Freeing the Overcontrolled Patient. New York: Guilford Press. Dobson, K.S. (1989). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology, 57, 414–419. Dobson, K.S. (Ed.) (1988). Handbook of Cognitive-behavioral Therapies. New York: Guilford Press. Haaga, D.A. & Davison, G.C. (1991). Disappearing differences do not always reflect healthy integration: an analysis of cognitive therapy and rational-emotive therapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 1, 287–303. Lazarus, A.A. & Lazarus, C.N. (1991). Multimodal Life History Inventory (2nd edition). Champagne, IL: Research Press. Mahoney, M.J. (1993). Introduction to special section: Theoretical developments in the cognitive therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2, 187–212. McGinn, L.K., Young, J.E., & Sanderson, W.C. (1995). When and how to do longerterm therapies without feeling guilty. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 2, 187–212. Neimeyer, R.A. (1993). An appraisal of constructivist therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2, 221–234. Robins, C.J. & Hayes, A.M. (1993). An appraisal of cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 6, 205–214. Safran, J.D. & Segal, Z.V. (1990). Interpersonal Processes in Cognitive Therapy. New York: Basic Books. Schmidt, N.B. (1994). The Schema Questionnaire and The Schema Avoidance Questionnaire. Behavior Therapist, 17, 90–92. Schmidt, N.B., Joiner, T.E., Young, J.E., & Telch, M.J. (1995). The Schema Questionnaire: Investigation of psychometric properties and the hierarchical structure of a measure of maladaptive schemas. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 19, 295–321. Segal, Z.V. (1988). Appraisal of the self-schema constructs in cognitive models of depression. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 147–162. Young J.E. (1990). Schema Grid. (Available from the Cognitive Therapy Center of New York, Suite 530, 120 East 56 Street, New York, NY 10022.) Young, J.E. (1992). Schema Conceptualization Form. (Available from the Cognitive Therapy Center of New York, Suite 530,120 East 56 Street, New York, NY 10022.) Young, J.E. (1994a). Cognitive Therapy for Personality Disorders: A Schema Focused Approach (Revised edition). Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press. Young, J.E. (1994b). Young Parenting Inventory. (Available from the Cognitive Therapy Center of New York, Suite 530, 120 East 56 Street, New York, NY 10022.) Young, J.E. (1994c). Schema Diary. (Available from the Cognitive Therapy Center of New York, Suite 530, 120 East 56 Street, New York, NY 10022.) Young, J.E. (1996). Schema FlashCard. (Available from the Cognitive Therapy Center of New York, Suite 530, 120 East 56 Street, New York, NY 10022.) Young, J.E. & Brown, G. (1994). Young schema questionnaire (2nd edition). In J.E. Young, Cognitive Therapy for Personality Disorders: A Schema Focused Approach (Revised edition). Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press. 222 Jeffrey E. Young Young, J.E. & First, M. (1996). Schema Modes. (Available from the Cognitive Therapy Center of New York, Suite 530, 120 East 56 Street, New York, NY 10022.) Young, J.E. & Flanagan, C. (1994). Schema-focused therapy for narcissistic patients. In E. Ronningstam (Ed.), Disorders of Narcissism – Theoretical, Empirical, and Clinical Implications. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Young, J.E., & Klosko, J. (1993). Reinventing Your Life. New York: Plume. Young, J.E., Beck, A.T., & Weinberger, A. (1993). Depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.), Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders (2nd edition). New York: Guilford Press. Chapter 9 Letting it go Using cognitive therapy to treat borderline personality disorder Susan B. Morse Cognitive therapy has been proven to be effective for the treatment of unipolar depression (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) and anxiety disorders (Beck, Emery, & Greenberg, 1985). This theory and some of the techniques have also been applied to the treatment of personality disorders (Beck, Freeman, & Associates, 1990; Young, 1990; Layden, Newman, Freeman, & Morse, 1993). This chapter will focus on what may be the most complex of all the personality disorders: the borderline. Many of the same issues arise in the treatment of the borderline patient as in the treatment of depression and anxiety. However, there are some additional problems which occur with this special and challenging patient. This chapter will attempt to address those issues which are different from the more standard cognitive therapies and give the reader a conceptualisation and techniques which will light a path toward health for these patients. Diagnosis and identification of the borderline patient Some therapists can spot a borderline patient immediately, but they may also be overdiagnosing this disorder. There are many signs that lead to a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD). The DSM-IV (APA, 1994) defines a BPD as “A pervasive pattern of instability of mood, interpersonal relationships, and self-image, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts”, as indicated by at least five of the following: 1 A pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterised by alternating between extremes of overidealisation and devaluations. 2 Impulsiveness in at least two areas that are potentially self-damaging, such as spending, sex, substance abuse, shoplifting, reckless driving, or binge-eating (do not include suicidal or self-mutilating behaviour covered in criterion 5). 3 Affective instability: marked shifts from baseline mood to depression, 224 4 5 6 7 8 Susan B. Morse irritability, or anxiety, usually lasting a few hours and only rarely more than a few days. Inappropriate, intense anger or lack of control of anger – for example, frequent displays of temper, constant anger, recurrent physical fights. Recurrent suicidal threats, gestures, or behaviours, or self-mutilating behaviour. Marked and consistent identity disturbance manifested by uncertainty about at least two of the following: self-image, sexual orientation, longterm goals or career choice, type of friends desired, preferred values. Chronic feelings of emptiness or boredom. Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment (do not include suicidal or self-mutilating behaviour covered in criterion 5). In addition to these criteria, there are some other signs identified by Layden et al. (1993), which may serve as markers or signposts leading the way to diagnosis: 1 The patient states, “I’ve always been this way. This is who I am.” 2 The patient demonstrates ongoing non-compliance with the therapeutic regimen (especially indicative of BPD when the patient is uncooperative in a hostile manner). 3 Therapeutic progress seems to come to a sudden halt for no apparent reason. 4 The patients seem entirely unaware of the negative effects of their behaviour on others. 5 The patients’ personality problems appear to be acceptable to them. Motivation for change is very low. 6 The therapist has very powerful, potentially antitherapeutic reactions to the patient. This feeds into the BPD patient’s propensity for mistrusting the therapist. 7 The patient misses many therapy sessions, arrives late for many sessions, and sometimes leaves abruptly during sessions. 8 The patient exhibits an extreme all or none thinking style. 9 The patients have difficulty moderating or modulating their emotional reactions, especially outbursts of anger. 10 The patient frequently does things that cause some sort of self-harm. These signs may indicate the existence of any personality disorder but, taken in combination with the DSM-IV criteria, are very helpful in identification of the BPD patient. There is a large intradiagnostic variability within the BPD group. It has been suggested by Kernberg (1975, 1984), Meissner (1988) and Layden et al. (1993) that BPD is more of a spectrum than a single discrete entity. The three subtypes identified by Layden et al. (1993) are: Cognitive behaviour in borderline personality disorder 1 2 3 225 Borderline–avoidant/dependent. Borderline–histrionic/narcissistic. Borderline–antisocial/paranoid. These hypothetical subdivisions of BPD have been extremely helpful in conceptualising these patients more clearly. The subdivisions also help to prioritise goals for these patients when the things they need to work on can seem overwhelming. Understanding these distinctions has critical implications for conceptualisation. The borderline–avoidant/dependent patient displays high levels of anxiety, low levels of competence (often due to avoidance), and very low self-esteem. They often have an underdeveloped sense of self and have difficulty maintaining boundaries in any relationship, including therapy. They alternate between distancing people and the need for constant reassurance. This movement between mistrust of intimacy and extreme dependency causes this type of patient to appear highly anxious and often dysthymic. The behavioural strategies they engage in are avoidance, withdrawal, clinging, and neediness, and they will display high levels of anxiety. The borderline–histrionic/narcissistic patient displays mood lability, stormy relationships, and overwhelming need for affection and attention. Their fears related to abandonment and unloveability decrease their ability to understand and respect interpersonal boundaries. These patients appear to desire stimulation but its focus is external. The need for changes within the self is not recognised. They are therefore resistant to therapy and often use all of their resources to thwart progress. The behavioural strategies they engage in are rage reactions, impulsivity, impatience, low frustration tolerance and overinvestment in relationships which have not yet matured. The borderline–antisocial/paranoid patient shows a marked disregard for the rules that govern behaviour; whether these rules are formal (laws, religious mores) or informal (moral, polite, socially based) makes no difference to this patient. They put themselves first because there is no recognition of others’ rights. They display a chronic and pervasive distrust of the motives of others and are hypervigilant to any sign of threat. These patients, although they may look the same as “pure” antisocial/paranoid, are motivated out of extreme emotional pain and helplessness. These patients display hostility, suspiciousness and recklessness. They have a low tolerance for boredom which often leads to substance abuse. The behavioural strategies these patients display are aggression, substance abuse, low impulse control and destructive behaviours which may be directed inward or outward. Once you diagnose a borderline personality disorder and identify the subtype they resemble most closely then it is time to begin the work of cognitive therapy. 226 Susan B. Morse Cognitive conceptualisation of borderline personality disorder The cognitive components which truly define a borderline personality disorder are the nature of their schematic systems. Schemas in this sense refer to unconditional beliefs about the self in relationship to the world. These core beliefs or schemas are based on a person’s perception of events and assist in the maintenance of negative behaviours. These schemas are developed early in life and are maintained through negative cognitive sets and emotions. It is through identification, challenge and modification of these belief systems that the borderline patient can change. Schemas can be dormant or active. These beliefs are often activated by a trigger or any event which is perceived by the patient as traumatic. For example, a patient may not believe that they are unloveable if they are in a relationship. When the relationship ends, the schema may be triggered and they then believe at 100% that they are not loveable. One of the first goals in cognitive therapy is to help the patient identify their schemas and the situations, emotions, or thoughts which trigger them. In order to do this you must teach each patient to identify and understand the levels of cognition. Levels of cognition There are three levels of cognition which must be addressed in the treatment of any personality disorder. Patients must be able to identify all levels of cognition as they begin to help themselves with therapy. One of the easiest ways to remember these levels and to teach them to patients is with the “tree” example shown in Figure 9.1. It goes like this: the Automatic thoughts Conditional beliefs and assumptions Schemas or core beliefs Figure 9.1 Levels of cognition. Cognitive behaviour in borderline personality disorder 227 first level of cognition or thought is the automatic thought level. It is like the leaves and the branches of the tree. You can see all the different shapes and sizes. You can see the whole shape or look at each little leaf. The branches and leaves blow in the wind, get wet when it rains and in general are very reactive to the environment. They are easy to access, you can pluck them from the tree or break off a branch. Automatic thoughts are like this in that you can access them, they are reactive to the environment and you can change them with relative ease. The second level of thought is the conditional beliefs or assumptions. They are like the trunk of the tree. You can see the shape and size but to see each growth ring you must look inside. It responds to the environment but not as easily. It connects the roots to the branches and leaves. You must use a tool like a saw or a knife to change the trunk. Conditional beliefs are like the trunk of the tree. You must look for them, they are harder to change than automatic thoughts and they come in “If . . . then” form which connects the schema to the automatic thoughts. The lowest level of cognition is the schema or core belief. These thoughts are like the roots of the tree. You cannot see the size or the shape. You do not know the number. They filter all the information and nutrients to the upper levels. They are as old as the tree and have grown and modified over the life of the tree. To identify and change them you often need to uproot the entire tree. Schemas are like the roots of the tree, you must look hard for them, they “hold” the personality together and all information is filtered through them. As the therapist you will need to hypothesise which beliefs and thoughts are giving the patient trouble. Once you have identified these cognitions you must help the patient learn to respond to these thoughts. Before you can challenge and change the hypothetical schema you have identified, you must stabilise your patient’s behaviour and emotions. You can do this by decreasing the responses that are generated at a schematic level. This needs to be done by working on the automatic thought level with the patient on standard cognitive therapy for Axis I issues. The ability to identify and challenge automatic thoughts builds a “buffer” between the patient and the environment. One patient described it as “feeling like I have skin for the first time”. These patients react with such strong emotion because schemas have been activated by a trigger. As they increase their ability to identify and respond to daily stressors they decrease their reactive responses. When schemas remain protected they do not force the use of the dysfunctional behaviour strategies. Therefore if a patient can respond to triggers, situations and negative emotions such as depression and anxiety on an automatic thought level they will be less likely to respond at a schematic level. Once the patient can keep the “present in the present” and the “past in the past”, they can begin to change their schemas. You have a much more difficult time changing schemas when they are being activated than when they are 228 Susan B. Morse dormant. In addition to the levels of cognition, you must teach the borderline patient about schema development. Schema development Educating yourself and your patients about the impact of schemas is the beginning of understanding their behaviour. You want to help the patient identify their schemas and to look at how they came to believe these things about themselves. Looking at their developmental history often provides the answers to this question. There are several developmental issues which apply to the development of borderline personality disorder. 1 2 3 4 Content of the schema. The Eriksonian stages of the patient’s life relevant to the times when the schemas were acquired and reinforced. The perceptual channels through which the schema building information was received and stored. The Piagetian level of cognitive processing relevant to the schemas. This information needs to be collected so that the development and maintenance of the schemas can be understood by both therapist and patient. Content of schemas One of the most useful components of cognitive therapy is that the therapist uses the client’s materials to build a conceptualisation. One is not bound by a static theory into which all patients must fit. Schema content is as individual as the patient. The words the patient uses to describe their experiences make up the schema content. If, however, some assistance in identification of schemas is needed, Schema-focused Cognitive Therapy for Personality Disorders: A Schema-focused Approach by Jeffrey Young (1990) provides a self-report list of potential schemas for the client to complete. Some of these fall into the following categories: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Independence Subjugation/lack of individuation Vulnerability to harm and illness Fear of losing control Emotional deprivation Abandonment/loss Mistrust Social isolation/alienation Unloveability/defectiveness/badness Social undesirability Cognitive behaviour in borderline personality disorder 11 12 13 14 15 229 Guilt/punishment Incompetence/failure Unrelenting standards Loss of emotional control Entitlement/insufficient limits In addition to these categories, Aaron T. Beck hypothesises that there are two underlying themes for schemas – unloveability and competence. As your patient presents you with information about their belief system you can refer to these content areas. Eriksonian stages associated with schema development Eriksonian theory provides us with a frame for schema development which uses the same language as the patient to describe their belief system (Erikson, 1963). There are two ways to look for this developmental information. First, when the BPD patient uses words like trust or competence you can explore the patient’s history in an attempt to explain the origin and process by which the patient came to believe the schema. The way Eriksonian stages are associated with schema development is illustrated in Table 9.1. Table 9.1 Eriksonian stages associated with schema development Age 0–18 months 18 months to 3 years 3 years to 6 years 6 years to puberty Erikson’s Stages Trust versus mistrust Autonomy versus shame and doubt Initiative versus guilt Competence versus inferiority Schemas Mistrust Dependence Abandonment Lack of individuation Shame Embarrassment Dependence Guilt Punishment Powerlessness Incompetence Failure Unloveability and defectiveness For example, Sally believes that she “isn’t good enough”. As this statement was explored further she stated she believed “I am bad”. By looking at her developmental history we identified that she was two and one half years old when her brother was born prematurely and there were expectations that she “behave” because her brother and mother were ill. During this stage of development (18 months to 3 years) it is the child’s “job” to explore their world, work on toilet training and begin to separate from the mother. It is easy to see how parents with a sick baby may not have been extremely patient with an exploring two year old. She was verbally reprimanded and took on this 230 Susan B. Morse information in the form of a core belief. Her behaviours also mimic this stage of development. She displayed extreme anxiety whenever she tried anything new and she would switch between dependence and defiance in relationships at work and at home. Once this information was presented to the patient we could begin to work on challenging it rather than constantly responding to it. Each stage needs to be explored in order to identify beliefs and behaviours which may have developed in each phase. After identification the process of change and decreasing reinforcement begins. The procedures used to facilitate this change will be covered in the techniques for treatment section. Channels of input In order to remediate and challenge a belief you must be able to “get to it”. In other words, to address the belief through the channel of development. There are several methods by which information is processed. Sensory: This is all the information that comes into a child’s world through the senses. Sights, smells, sounds, taste, and tactile memories may be part of this channel of input. We process information less in the sensory mode as we grow older, so triggers and schemas stored in this way reflect early experiences (Figure 9.2). Images: This is the visual channel and can involve all sorts of visual information, faces, expressions, pictures, even images from the media or movies. When accessing images, you need to look for two types of visual pictures. The first type is like a snapshot and is frozen in time. The other type of image presents itself in movie form. Verbal Images Sensory 0 1 2 3 4 Age (years) Figure 9.2 Channels of input in relation to age. 5 6 7 Cognitive behaviour in borderline personality disorder 231 Verbal: this is the most common channel through which information is expressed – the use of words and abstract concepts. Most developmental information from 8 years of age will be stored in verbal memory unless there was a severe trauma that decreased processing ability. When children are developing they receive information on a variety of levels. In order to remediate a belief the therapist must understand how the child came to believe this schema. Many patients will say that they feel things but do not have the words for these feelings. This may be because they (the feelings) are stored in modalities other than verbal. The type of input affects the choice of intervention. Triggers and strategies are also related to channel of input. I once treated a patient who had been the victim of severe emotional, physical, and sexual abuse as a child. She had been diagnosed as borderline with psychotic features. She had gone through years of therapy and had made little progress. She was only 25 and had used up her lifetime medical supplement. We began working on her issues while she was in inpatient treatment. One day after a session we were walking toward the hospital cafeteria. Unlike many hospitals this one had a wonderful chef who baked a chocolate chip pie for the patients and staff on special occasions. Most of the people in the hospital responded positively to the smell of the pies baking. The patient and I were walking and talking after what we thought was a productive session. As we neared the door to the cafeteria, she broke out into a sweat, started screaming and ran toward the bathroom. I followed her and found her in the fetal position in the corner of the toilet. After making sure she was safe and moving her to a more comfortable room, I began to question her about what had happened. “Was it something that happened in session?” “No.” Was it someone we saw in the hall?” “No.” “Was it the temperature? Something I said?” I was desperately searching for a trigger for this outburst. “Was it a smell?” Then there were many tears and she was able to recall that while she was being sexually abused by her father and his friends, her father’s girlfriend would bake chocolate chip cookies to keep the kids quiet. She had no words to explain her outburst but when she was able to focus on the sensory triggers she was able to identify the source of her distress. To everyone else and to herself this behaviour looked crazy but once she understood the trigger she could understand her reaction. A year later around Christmas time she placed an emergency call to me. She had been out shopping with a friend and he was trying on cologne. She ran out of the store disoriented and stopped herself to call me. She told me in a breathless voice, “He (her father) wore Old Spice. I’m not crazy.” So after a year of identification of triggers and learning to cope with the response, she was able to identify, attribute and cope with her response rather than to use the incident to reinforce her negative schema (I’m crazy). By giving the patient some type of explanation for their reactions and behaviours you can decrease the negative outcomes as well as reduce the schema reinforcement. 232 Susan B. Morse Piagetian stages The Piagetian interpretation provides yet another necessary piece to the BPD puzzle (Piaget, 1952). We expect that people develop according to the normal course of development. When someone deviates from that course we expect to see across the board, consistent arrested development. The borderline patient, however, often handles some problems very well, but uses extremely immature and maladaptive strategies for other problems. This can be very frustrating to the therapist and many cause the patient to be labelled as “in denial” or “repressing”. These labels imply intent and they result in negative reactions from therapists and other support people. It is a hypothesis in cognitive therapy that these behaviours represent a skills deficit which originated in an unnegotiated stage of development. Table 9.2 shows the stages of development according to Piaget and the corresponding borderline characteristics. Table 9.2 Parallels between Piagetian and borderline characteristics Piagetian stage Piagetian characteristic Similar borderline characteristic Sensorimotor (0 to 2 years) Egocentrism Enmeshment, fear of engulfment, fear of loss of identity, dependency, sense of entitlement, egocentrism in speech Lack of empathy, inability to conceive of alternative explanations, no search for evidence Abandonment schema Lack of empathy Lack of object permanence Preoperational (2 to 7 years) Centring Affective realism Overgeneralisation, confusion of “the then with the now”, confusion of sex with intimacy Dichotomous thinking, catastrophising, perfectionism, unloveability schema Inability to generalise conclusions, vacillation between schemas Emotional reasoning Logical thinking Inability to be logical Theoretical thinking Lack of theory construction Metathought No metathought, inability to see hypotheticals Inability to seriate Transductive reasoning Concrete and formal operations When these behaviours are present it is likely that a schema has been activated. This will often render standard cognitive therapy techniques useless. It Cognitive behaviour in borderline personality disorder 233 is the job of the patient and therapist to identify the stage of development where the patient is stuck and develop a treatment plan for the remediation of this problem area. Treatment of the borderline patient is not extremely difficult but in order to address all these issues (along with the crisis of the day), the therapist needs an arsenal of techniques and a clear treatment plan. Case conceptualisation The first step in good cognitive therapy is a clear understanding of the patient. We have just discussed the stages of development and issues connected with schema activation in theory. Case conceptualisation involves combining a specific patient’s information with this theoretical data to develop a treatment plan. You need to identify which area of the patient’s problems are the most destructive to the patient and also find an area that may be easy to change. The reason you need to enter the conceptualisation in two areas is to keep the borderline patient safe from any destructive behaviours and to address the hopelessness with some positive movement. If you can help the patient change just one thing then you can decrease the level of hopelessness and increase the likelihood that they will comply with more intense behavioural interventions. In order to choose where to start, it may be helpful to complete a case conceptualisation worksheet on each patient. It may seem like it is a lot of work outside the session but it will save you effort and problems throughout the course of treatment. The following is a sample of a case conceptualisation worksheet: CASE SUMMARY AND COGNITIVE CONCEPTUALISATION WORKSHEET Patient’s initials: Date: I. Identifying information II. Diagnoses: Axis I: Axis II: Axis III: Axis IV: Axis V: III. Objective scores: Intake Session 1 BDI BAI Session 2 Session 3 Session 4 Session 5 234 Susan B. Morse HS Other General trend of scores: IV. Presenting problem and current functioning V. Developmental profile A. History (family, social, educational, medical, psychiatric, vocational) B. Relationships (parents, siblings, peers, authority figures, significant others) C. Significant events and traumas (combine with stage of development and channels of input) VI. Cognitive profile A. The cognitive model as applied to this patient: 1. Typical current problems and problematic situations 2. Typical automatic thoughts, affect, and behaviours in these situations B. Core beliefs/schemas (Unconditional statements about the self in relationship to the world and others) C. Conditional beliefs (If–then statements which connect the schemas to the present automatic thoughts) D. Rules (shoulds/musts applied to self–others) VII. Integration and conceptualisation of cognitive and developmental profiles A. Formulation of self-concept and concepts of others B. Interaction of life events and cognitive vulnerabilities C. Compensatory and coping strategies D. Development and maintenance of current disorder VIII. Implications for therapy A. Suitability for cognitive interventions (rate low, medium, or high, and add comments if applicable) 1. Psychological mindedness 2. Objectivity 3. Awareness 4. Belief in cognitive model 5. Accessibility and plasticity of automatic thoughts and beliefs 6. Adaptiveness 7. Humour B. Personality interaction with external environment 1. Sociotropic (focus and emphasis of life on other people) Cognitive behaviour in borderline personality disorder 235 2. Autonomous (focus and emphasis on power and independent functioning) C. Patient’s motivation, goals, and expectations for therapy D. Therapist’s goals 1. Most dangerous problem for this patient: 2. Problem most likely to change with relative ease 3. Skills training stages E. Predicted difficulties and modifications of standard cognitive therapy This worksheet will assist you in addressing the concerns you may have as to how to begin your treatment with this difficult population. Clarification of the patient’s history and current level of functioning will provide you with a place to start. The next section on treatment will assist you in how to modify standard cognitive therapy for these patients. Techniques for the treatment of the borderline patient There is a greater use of the therapeutic relationship as a vehicle for change in the treatment of the borderline patient. Many therapists learning cognitive therapy for the borderline patient become worried that they are not doing enough thought records or that the patient is not compliant with their homework. Although these are both important elements of the treatment, you must take time to build a relationship with this patient. This does not mean just sitting and listening but helping them begin to change the things that are easier for them to change. People begin to trust therapy and the process more quickly if the benefits are concrete and noticeable. The course of treatment in cognitive therapy has been a topic for researchers looking for the best and shortest intervention time for disorders like depression and anxiety. The treatment of the borderline patient has yet to be researched in this way. There are, however, some adjustments which need to be made to standard cognitive therapy for this population. In the treatment of Axis I disorders such as anxiety and depression, the therapist has to socialise (or teach the cognitive model of thoughts– feelings–behaviours) the patient only at the beginning of treatment. With the borderline patient the therapist must continue to explain the cognitive model in a variety of situations; it appears that these patients are less likely to generalise this concept than other patients. For example, if you teach a depressed patient to monitor his thoughts at work, he may return the next week and tell you he monitored his thoughts in a fight with his wife and it was helpful. Generalisation has occurred and he is able to use his skills in order to handle his thought in a variety of situations. A BPD patient with the same socialisation may not even be able to see how it works in a situation which is very 236 Susan B. Morse similar to the practice situation. Each piece of information contains different clues to the patient and it is too difficult to see the similarities. Therapists have a tendency to think that the patient is being difficult when obvious connections are not made. This does not seem to be the case and this should be seen as an opportunity to resocialise the patient with this particular set of circumstances. The use of an agenda in cognitive therapy is something that separates it from other types of therapy. The use of structure and agenda setting is a very powerful tool in the treatment of the borderline patient. Structure in the session provides an opportunity for the patient to practise prioritising their emotional turmoil and to begin to make some progress in changing their behaviours. Therapists are often unsure as to whether to be structured with these patients as their emotional needs seem to overpower any other items which may need to be talked about. It is very important to stick to your agenda setting, giving homework, teaching skills, and prioritising your topics with this population. Cognitive therapy with this group is less Socratic and more confrontive. It is not necessary in the treatment of Axis I patients to “tell” or “interpret” their thoughts or perceptions for them. It is the therapist’s job to ask questions in a Socratic fashion in order to allow the patient to answer and interpret his own thoughts and motivations. With the borderline patient, it is often necessary to be more direct and to guide them in a concrete fashion to an understanding of their thoughts. One note of caution here is not to “lead” a patient to a hypothetical explanation of the origins of their schemas or behaviours. The false memory syndrome is created by therapists doing just that. There are many explanations for developmental problems and it is not always necessary to “know for sure” what caused these beliefs. It is more important to buffer the schemas and increase the patient’s functioning in the present. Therapy for the borderline patient focuses on the historical and developmental factors for each patient. You should gather this information in a timely fashion, for example sending home to the patient a packet of questions which would provide you with the information you require to develop a conceptualisation and begin treatment. You do not need to gather an entire history in person or allow the patient to talk through these historical issues. They are extremely important in your treatment but the emphasis needs to be on the here and now and problem-solving techniques in the present. Talking about their history is not something that will help this patient at the beginning of therapy. The first set of techniques you should teach a borderline patient is anxiety management. Any change will cause anxiety and schemas will be activated by anxiety. These patients do not manage their anxiety well and this often leads to their most problematic behaviours. If you spend the first few sessions working on anxiety management skills it will decrease some of the avoidance Cognitive behaviour in borderline personality disorder 237 and will increase the likelihood that therapy will not come to a mysterious halt. If you want the patient to begin to feel competent, you should teach them how to deal with this anxiety and do not move into intense schema work or behavioural change work until you know that the patient has a minimal level of skill in this area. There needs to be a focus on the strategies that borderline patients use to decrease their discomfort. Try to identify all the methods that these patients use to “calm” themselves down. The patient’s dysfunctional strategies to manage problems (such as cutting, drinking, rages) may be activated by anxiety. It is important to assist the patient to develop the skills to manage these situations. Next you will need to teach the patient the difference between anger and anxiety. These two emotional states manifest themselves in a similar fashion physically. Often the borderline patient cannot tell the difference and will respond with anger when they are really anxious about something. The one main difference between anger and anxiety is the content of the cognitions. The thoughts which precede anxiety have a theme of dangerousness and the thoughts which precede anger have a theme of injustice. If you can assist the patient in telling the difference between the two, you will see a reduction in the degree of anger the patient displays. So you have worked on anxiety versus anger, anxiety management skills, collected some objective data (scores on the Beck Depression Inventory, Beck Anxiety Inventory, Hopelessness Scale, etc.), you have gathered your history and are always working on a therapeutic relationship. Now you are ready to begin the cognitive techniques in earnest. The BPD patient’s cognitions are idiosyncratic and often quite distressing to the patient as well as the therapist. Therefore it was necessary to modify the Dysfunctional Thought Record (Beck et al., 1979) to fit the cognitive set of the borderline patient. Instead of just asking that the patient record their automatic thoughts or stream of consciousness you will need to ask for specific information. For example, there was a BPD patient who was in treatment for a number of years with many therapists. She continued to have problems and difficulties with her daily life and was unable to do normal activities, which made her life very complicated. She needed a new car but was terrified to go to the car dealer to buy one. Because she was unable to do that her car broke down often, making her late for work and she would miss appointments and dates. She began to get negative feedback from her supervisor at work and her friends were always upset with her. This activated her schemas of unacceptability and unloveability and she engaged in her negative strategies to try to make herself feel better. The first step was to get her to solve the problem of the car. Her homework was to go to the car dealer and fill out a thought record with whatever went through her mind. Figure 9.3 shows the thought record, Part 1, completed by her for that assignment (Figure 9.3). 238 Susan B. Morse SITUATION: Sitting in car dealership remembering miscellaneous events of sexual, emotional or physical abuse over the years. EMOTIONS: 1.Angry DEGREE = 100% 2. Sad DEGREE = 100% 3.Anxious DEGREE = 100% AUTOMATIC THOUGHTS: I am ready to give up. No therapy can release all the pain. I know I have the right to live and be happy, but the planet earth seemingly insists by its practices that I don’t have the right. IMAGES: The car dealer puts his hand over my mouth and throws me down. He rapes me. I just lie there. SENSATIONS: Can’t get my breath. Pressure on my chest. Pain in my back. MEMORIES: Being grabbed and thrown to the ground by assailant. Father grabbing my arm and almost breaking it. Figure 9.3 Thought record – Part 1. It can be seen from the figure that if the therapist had focused on just the thoughts, there would have been little progress. These thoughts are hopeless but are not related to the situation and would be extremely difficult to challenge as we do not know the motivation of “planet earth”. But looking at the images gives us a clear picture of why the patient would not go into the dealer. Remember that people only act on the thoughts they believe and no one would do something if they believed that rape would be the outcome. This patient had been raped in the past and the sensations she records here are sensations that she recalls from the rape. So once she had the image and her body reinforced the memory she was unable to force herself to go and buy a car. By completing this thought record we gathered a great deal more information and information which allows us to solve the problem. We increased her safety factors (going with a friend, staying in the showroom, not being alone with the salesman), had her do some standard image work to generate some positive images, used relaxation to decrease the body sensations, and she was then able to go into the dealer and purchase a car. This not only solved the problem with the car but all the resulting difficulties from its unreliability. In addition, we looked at her thoughts in a more specific and here and now fashion. After some questioning about the situation at the car dealer she was able to generate the thought, “I will always be taken advantage of ”. This was a thought which occurred frequently and to which she was unable to respond. We completed a thought record, Part 2, in order to help her develop an adaptive response to this thought (Figure 9.4). It is often difficult for the patient to generate the evidence against their own negative thoughts and that is where the skill of the therapist comes into play. You must assist the patient in finding a way to look at their history in an objective fashion. When you are challenging the cognitive process in a borderline patient, you Cognitive behaviour in borderline personality disorder 239 AUTOMATIC THOUGHT: I will always be taken advantage of BELIEF IN AUTOMATIC THOUGHT (0–100) = 100% EMOTION: Anger DEGREE (0–100) = 100% 1. What’s the evidence? (pro) I have been raped, abused, used for other people’s whims (con) I have been able to take some steps in life WITHOUT ABUSE (Rent an apartment) 2. What are the errors in thinking? Overgeneralisation, selective abstraction 3. What’s an alternative viewpoint? Sometimes I will do all right and not be taken advantage of. But I may be taken advantage of at other times 4. What’s the worst that can happen? I will live just to provide others with a scapegoat What’s the best that can happen? Nobody will ever take advantage of me again What’s the most realistic outcome? Some people will continue to try to take advantage of me 5. What positive action can I take to make change? Assertively state what I need to do for me. Avoid certain people and situations when I feel weak 6. What’s the effect of my thinking? Anger, fear, become immobilised, punish myself RERATE BELIEF IN AUTOMATIC THOUGHT (0–100) = 0% EMOTION: Relief DEGREE (0–100) = 100% SUMMARY OF ADAPTIVE RESPONSES: Even though I have had people take advantage of me throughout my life, it may change. I have been able to deal with some people and not feel taken advantage of in the past few years. If I can be assertive about my needs and adaptively respond to my thoughts, I may be able to increase the positive things that can occur in my life. Figure 9.4 Adaptive responses: Thought record – Part 2. need to use a response that fits each level. For thoughts, respond with words. For images, use image work. For sensations, use anxiety management and comforting sensory techniques. For memories, use a method of exploring the memories which allows the patient to put these memories in their place and keep them from being activated in daily situations. The above techniques will be the majority of your treatment with the borderline patient but you will need to modify your treatment to fit the patient’s specific need. Make a list of all the diagnoses, the negative behaviours, the problematic situations and any goals the patient has and begin with one problem at a time. It will be slow work but very rewarding; if you can keep yourself and the patient from getting overwhelmed or giving up you will have a chance at successful treatment of the borderline patient. Here is a poem written by a patient after completing treatment. I. I walk down the street. There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I fall in I am lost . . . I am helpless It isn’t my fault. It takes forever to find a way out. 240 Susan B. Morse II. I walk down the same street. There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I pretend I don’t see it. I fall in again. I can’t believe I am in the same place but it isn’t my fault. It still takes a long time to get out. III. I walk down the same street. There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I see it there. I still fall in . . . It’s a habit My eyes are open. I know where I am. It is my fault, I get out immediately, IV. I walk down the same street. There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I walk around it. V. I walk down another street References American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: Author. Beck, A.T., Emery, G., & Greenberg, R. (1985). Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Perspective. New York: Basic Books, Beck, A.T., Freeman, A., & Associates (1990). Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders. New York: Guilford Press. Beck, A.T., Rush, A.J., Shaw, B.F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press. Erikson, E.H. (1963). Childhood and Society. New York: Norton. Kernberg, O.F. (1975). Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism. New York: Jason Aronson. Kernberg, O.F. (1984). Severe Personality Disorders. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Layden, M.A., Newman, C., Freeman, A., & Morse, S. (1993). Cognitive Therapy of Borderline Personality Disorder. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Cognitive behaviour in borderline personality disorder 241 Meissner, W.W. (1988). Treatment of the Borderline Spectrum. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson. Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. New York: International University Press. Young, J.E. (1990). Schema-focused Cognitive Therapy for Personality Disorders: A Schema-focused Approach. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Exchange. Chapter 10 Techniques and strategies with couples and families Frank M. Dattilio Cognitive therapy as applied to couples and families has evolved out of the behavioural school of thought, when theorists of this school first began to apply their techniques to couples in the 1960s. While there are reports that cognitive techniques were being applied to couples as early as the late 1950s (Ellis, Sichel, Yeager, DiMatlia, & DiGuisseppe, 1989), it was not until the late 1960s/early 1970s that the first published studies using behaviour therapy with couples appeared in the professional literature (Stuart, 1969; Liberman, 1970). The implementation of cognitive techniques in clinically controlled outcome studies actually occurred much later (Margolin & Weiss, 1978), with increasing attention attributed to the cognitive component during the 1980s and early 1990s. Initially, principles of behaviour modification were applied to the interactional patterns of family members, specifically to the marital dyad (Patterson & Hops, 1972). Behavioural therapy with couples was originally referred to as behaviour exchange theory and has more recently been referred to as the social learning model (Jacobson, 1991). Initially, behavioural treatment approaches placed emphasis on the components of social exchange and contingency contracting with couples (Bandura, 1977; Stuart, 1969, 1976) and later emphasised communications training (Jacobson, 1991). The eventual introduction of cognitive components (Ellis, 1977; Margolin & Weiss, 1978) sparked additional literature in the subsequent decade focusing on cognitive-behavioural techniques with dysfunctional couples (Baucom & Epstein, 1990; Beck, 1988; Dattilio, 1989, 1990a, 1990b; 1990; Dattilio & Padesky, 1990; Doherty, 1981; Epstein, 1992; Epstein & Baucom, 1998; Fincham & O’Leary, 1983; Margolin, Christensen and Weiss, 1975; Revenstorf, 1984; Schindler & Vollmer, 1984; Weiss, 1980, 1984). This movement in couples therapy underscored the need for treatment to focus on the cognitions that were held by couples regarding each other’s actions, suggesting that it should be an integral part of the change process. The underlying philosophy contends that behaviour change alone is insufficient to correct the dysfunctional interactions that are so often experienced by couples; thus, more emphasis must be placed on thethinking Techniques and strategies with couples and families 243 styles of individuals in relationships as well as the maladaptive behaviour patterns (Dattilio, 1990a, 1994). Cognitive theory and couples Ellis, one of the first theorists to suggest a predominantly cognitive approach with couples, proposed that marital dysfunction occurs when partners maintain unrealistic beliefs about the relationship and make extreme negative evaluations once dissatisfied. Ellis’s Rational Emotive Behaviour Approach (REBT) proposes that disturbed feelings in relationships are not caused merely by one mate’s wrongdoing or other adverse events, but by the views that partners take of each other’s actions and of life’s rough breaks (Ellis et al., 1989). He further contends that disturbed marriages result when one or both spouses hold irrational beliefs – irrational being defined as highly exaggerated, inappropriately rigid, illogical and absolutist. As a result of this irrational thinking, unrealistic and demanding expectations develop, producing disappointment and frustration when they are perceived as being violated. These responses, in turn, give rise to negative thoughts which contribute to negative emotions, leading to a vicious cycle of disturbance. Ellis promotes the challenge of the validity of spouses’ irrational beliefs and aims to teach them how to replace their faulty thinking with more realistic thoughts about themselves and their partners. Beck’s cognitive therapy with couples differs from Ellis’s theory by combining many of the insights from the psychodynamic therapies, along with several of the strategies first established by behaviour theorists (Beck, 1988). The more conventional approaches are combined within a cognitive framework with an emphasis on specific concepts involving general thinking styles, underlying beliefs about the relationship, and the nature of current interactions between partners. The fact that cognitive therapy is in part derived from classical psychoanalysis as well as cognitive psychology, behavioural theory and other contemporary systems of psychotherapy makes it a very integrable theory (Alford & Beck, 1997). Moreover, due to the fact that cognitive therapy draws its theoretical structure from such a wide variety of sources, Beck maintains that cognitive therapy is “the integrative therapy” (Beck, 1991). The primary tenets of cognitive-behaviour therapy as applied to couples involve: (a) the modification of unrealistic expectations in the relationship, (b) correction of faulty attributions in relationship interactions, and (c) the use of self-instructional procedures to decrease destructive interaction. A primary agenda of cognitive-behaviour therapy is identifying partners’ schemata or beliefs about relationships in general and, more specifically, their thoughts about their own relationship (Beck, 1988; Epstein, 1986) and how this effects their emotions and behaviours. Basic beliefs about relationships and the nature of couple interaction are 244 Frank M. Dattilio often learned early in life from primary sources such as parents, local cultural mores, the media, and early dating experiences. These schemata or dysfunctional beliefs about relationships are often not articulated clearly in an individual’s mind but may exist as vague concepts of what should be (Beck, 1988). These beliefs can, however, be uncovered by examining the logic and themes of one’s automatic thoughts. Automatic thoughts are defined as “surface thoughts” or ideas, beliefs or images that individuals have from moment to moment that are situation-specific (e.g., “My wife is late again; she doesn’t care about my feelings.”) Automatic thoughts usually stem from the individual’s schemata, which are underlying or more core beliefs that are inflexible and unconditional in character. Schemata develop early in life as a result of personal experiences as well as through parental and societal influences. They constitute the basis for coding, categorising, and evaluating experiences during the course of one’s life. The therapist working with couples from a cognitive perspective must focus equally on each partner’s expectations about the nature of an intimate relationship. In addition, the distortions in evaluations of experience derived from those expectations are critically important. For example, a husband who believes that his wife should be interested in everything that he has to say might expect her always to be attentive to him regardless of what else may be going on in her life. Cognitive therapy assumes that unrealistic expectations about relationships can erode satisfaction and elicit dysfunctional responses. For example, many couples enter a relationship with the belief that love spontaneously occurs between two people and exists that way forever without further effort. As a result, couples may experience a decrease in satisfaction once they realise that hard work is necessary to maintain their relationship. This expectation may also lead to inaccurate appraisals such as, “We probably were not right for each other from the start.” Epstein and Eidelson (1981) found that adherence to unrealistic beliefs concerning the nature of intimate relationships was predictive of distress level in relationships. Therefore, cognitive content is extremely important in accounting for dysfunctional responses to relationship conflicts. Cognitive distortions may be evident in the automatic thoughts that couples report and may be uncovered by means of systematic or Socratic questioning regarding the meaning that a partner attaches to a specific event. Spouses’ automatic thoughts about their interactions with one another commonly include inferences about the causes of pleasant and unpleasant events that occur between them. In his book Love is Never Enough, Beck (1988) has described several systematic distortions in information processing that occur frequently in automatic thoughts concerning relationships. For example, the thought “He always puts me down” is more likely to be an instance of generalisation than Techniques and strategies with couples and families 245 an accurate accounting of a spouse’s invariant behaviour. As another example, in the absence of concrete evidence, the thought “She thinks I am ignorant” would be an arbitrary inference. Cognitive therapy with couples focuses on the cognitions that are identified as components of relationship discord and as contributing to each partner’s subjective dissatisfaction with the relationship (Schlesinger & Epstein, 1986). This approach moves to the core of relationship difficulty by focusing on hidden as well as obvious here-and-now problems, rather than by dwelling on early childhood traumas. A wife, for example, may show explosive rage toward her husband. If he is not in fact responsible for provoking such intense anger, she may find that her rage has other meanings. One woman discovered by tracing her automatic thoughts and emotions that her rage was preceded by a feeling of helplessness. In fact, she had an image of herself as a young child, screaming to be heard by her mother. Once the therapy helped her identify this underlying fear that she would not be heard unless she screamed, she was able to begin to explore alternative methods of expressing her feelings to her husband. There are several major focal areas in the cognitive model that are essential when addressing the issue of change in relationships. These are described below. Beliefs about the relationship Basic beliefs are the foundation for individuals’ automatic thoughts and actions in any relationship. In order to understand these thoughts and actions, the therapist must work to uncover the basic belief system or “schema” and develop a clear understanding of how each spouse views the relationship and his or her role in relationships in general. As in the example of the wife who responded with destructive rage, the emphasis is placed on hidden, as well as obvious, here-and-now problems, as opposed to dwelling on early childhood traumas. Beneath her anger was a sense of vulnerability and helplessness. By uncovering this basic schema, the therapist was able to help her define ways in which she could be heard and share some control of her relationship without verbally attacking her husband. By discovering this underlying issue, she was further able to see that she viewed many relationships as manipulative and controlling even when they were not. Her view of herself as helpless and childlike had prevented her from being assertive about her own needs until she reached the point of expressing them in rage. By learning to assert her needs more consistently and to express her dissatisfaction in ways that her husband would comprehend, she was able not only to reduce her anger, but also to feel more empowered in the relationship. One method for achieving this behavioural change is the use of the “downward arrow technique”. This exercise was developed by Beck, Rush, Shaw, and Emery (1979) to track the anticipated outcome of automatic thoughts in order to help couples evaluate whether the expected catastrophe is likely to 246 Frank M. Dattilio occur. It is also used to identify the underlying assumption beneath one’s automatic thoughts and to uncover the hidden or core beliefs which we call schemata. This is done by identifying the initial thought; for example, “Harry doesn’t always listen to me,” and then asking the individual, “If so, then what?” in order to help the individual realise that such flaws are not necessarily fatal to the relationship. As Figure 10.1 shows, it is clear that screaming was this woman’s way of avoiding her perceived vulnerability. The use of the downward arrow exercise has served to uncover an underlying belief of vulnerability and helplessness along with her fear of losing control. This technique allows both the spouse and the therapist to see the chaining of thoughts and how they lead to erroneous conclusions and reinforce distorted beliefs. This technique is demonstrated very clearly on video by Dattilio (1996). Much of the cognitive approach involves ferreting out a couple’s basic beliefs and then collaboratively redefining key principles and restructuring the couple’s belief system. The amount of restructuring that is required varies, but it is recommended that the restructuring process be done with each person in the presence of their mate. By witnessing the testing and restructuring of beliefs, each partner is better able to provide support to the other later in the treatment process. Basic beliefs about the relationship are thus important in attempting to promote change with couples. Uncovering the basic belief system, then, allows the therapist to teach individuals the first step in altering their view of the relationship. Alternative versus distorted beliefs When working with couples, there is often disagreement over whether thoughts are balanced or distorted. In the cognitive approach, beliefs are designated as balanced if they have substantiating or supportive evidence. These are beliefs that are not convoluted by an individual’s biases or misperceptions. “Harry doesn’t always listen to me” ⇓ “I’ll never be heard” ⇓ “If I am not heard, I am a nobody” ⇓ “If I am a nobody, I’ll be helpless” ⇓ “If I am helpless, people will run over me” Figure 10.1 The downward arrow technique. Techniques and strategies with couples and families 247 Distorted beliefs, on the other hand, are beliefs which are based on misinformation or faulty thinking and are usually rooted in circumstantial evidence. An example of a common distorted belief is the statement, “All men are alike.” In the context of a relationship, this view carries negative connotations and represents a class of cognitive distortion called generalisation. If maintained under all circumstances, such a belief represents distorted thinking. Another example might be a husband who believes, “I must help my wife resolve every one of her dilemmas in order to be a good husband.” This again becomes a distorted belief when adhered to steadfastly. The alternative version of such statements usually includes more explanations with conditions attached. For example, for the belief, “All men are alike,” the more balanced view might be, “All men are alike in many ways, yet each is also unique.” In the example of the statement, “I must help my wife resolve every one of her dilemmas in order to be a good husband,” a more balanced alternative statement might be, “It’s important that I offer assistance to my wife when I can or be there for her when she needs me.” Distorted beliefs are often the basis of much dissension in relationships and need to be addressed quite specifically in order to introduce change in the relationship. They usually develop as a result of faulty thought patterns that become a part of the individual’s ordinary thought processes. Regardless of how they developed, the therapist’s role is to help weigh the existing evidence and test predictions made on the basis of the belief in order to assess its reasonableness. Unrealistic expectations The expectations that each person brings to the relationship create important dynamics in each union and have been a focus for most cognitive therapists treating distressed couples (Epstein, 1982; Jacobson & Margolin, 1979). With almost every relationship, individuals hold some anticipation with regard to the multitude of needs their partner will fulfil for them. The social learning model (Jacobson, 1991) refers to this as the “interaction between the stimulus value of behaviours received by each spouse and the way these stimuli are received and interpreted by the receiver” (p. 559). Very often, these expectations or anticipations lead to distortions and are transformed into unrealistic demands. It may take a while for some of these expectations to assert themselves in the relationship, which would account for why they often become issues only after a period of time, as opposed to during the courtship period. Beck (1988) and Ellis et al. (1989) contend that unrealistic or demanding expectations inevitably produce disappointment and frustration, which is often associated with negative interactions (e.g., hostility, badgering, etc.). A common example of this pattern occurs in the couple who enter a relationship with the expectation that love spontaneously occurs between two people and exists that way forever with virtually little or no further effort on either 248 Frank M. Dattilio partner’s part. Such couples experience deep disappointment and hurt when problems arise and may even erroneously conclude that their difficulties signal that the relationship was never really a good one. In this example, the unrealistic expectation is held by both spouses simultaneously; however, in many cases unrealistic expectations are held by one person in direct conflict with the other’s viewpoint. For example, one man who came from an environment where the father was the sole breadwinner expected his wife to be content in remaining home and not working outside the home. However, his wife was reared to believe that partners have equal rights, and this created a conflict over her wish to seek employment. Such expectations emanate from early conceptualisations about relationships, spousal roles, and individual needs. These conceptualisations are derived from primary sources such as parents, the media, and early dating experiences. They are usually blended with each partner’s personal ideas of how he or she would like the relationship to be. In addressing unrealistic expectations, the therapist must again refer to the root of both partners’ belief systems. The therapist identifies their cognitive schemata and teaches them first to label erroneous beliefs via comparisons and then to test these beliefs against alternative evidence. This is usually done one step at a time. It is important to go slowly and not to do this too abruptly. It is essential to remember that individuals have become dependent on these underlying belief structures, and attempting to remove them too quickly may elicit resistance from either partner. Causal attributions and misattributions Causal attribution is a formal term for “directing blame” in the relationship. It is not uncommon for spouses to arrive for therapy in a vicious blaming cycle which is propelled by anger, resentment, and the refusal of both to accept responsibility for the dysfunction in the relationship. Consequently, there exists an externalisation of blame and a misattribution of the problem to the actions of the partner. If they are both stubborn individuals, then the couple remain in a deadlock in which they inadvertently attempt to place the therapist in the uncomfortable position of determining who is to blame. Some authors believe (Abrahms, 1982) that conflict resolution or communication training is impossible unless both partners are willing to collaborate. The term “collaborative set” was coined by Jacobson and Margolin (1979) to indicate the need for both partners to behave in a manner that suggests that they view their conflicts as mutual and to realise that the conflicts are likely to be resolved only by working conjointly to solve them. Even if this stance is adopted overtly, couples may individually harbour thoughts about the attribution of blame which will later infiltrate the relationship. Therefore, another important step in the restructuring process involves helping both partners to accept responsibility for the distress in the relationship. This Techniques and strategies with couples and families 249 requires discussions and evaluation of the causal attributions each partner has made for the relationship problems. Assessment Because of the high rate of divorce and the heavy media emphasis on troubled relationships, most of the existing literature on cognitive-behavioural assessment of intimate relationships has focused on couples; relatively little has been published regarding the assessment of families. Although cognitivebehavioural family assessment is similar to that with couples, less emphasis is placed on the use of structured inventories and questionnaires, particularly because some family members may be too young to complete such forms or simply may find this to be a monotonous process. Nevertheless, inventories may be useful with older family members who can appreciate the benefit of identifying cognitions and behavioural interaction patterns on paper. There are numerous self-report and behavioural methods for assessing couples and families. Unfortunately, space limitations preclude a detailed presentation in this text. For a more comprehensive overview, the reader is referred to Baucom and Epstein (1990) and Dattilio, Epstein, and Baucom (1998). Assessment of relationship cognition Self-report questionnaires Considering the rapid growth of cognitive-behavioural couples and family therapy, there are relatively few self-report scales available for assessing the major types of relationship cognitions mentioned previously. Eidelson and Epstein’s (1981) Relationship Belief Inventory (RBI) was developed to tap unrealistic beliefs about close relationships, and it includes subscales assessing the assumptions that partners cannot change a relationship, that disagreement is always destructive, and that heterosexual relationship problems are due to innate differences between men and women, as well as standards that partners should be able to mindread each other’s thoughts and emotions and that one should be a perfect sexual partner. Although the RBI covers a limited range of potentially problematic assumptions and standards, it has been used widely in research and clinical practice, and therapists can use it as a springboard for broader discussions with couples concerning their personal beliefs. Baucom, Epstein, Rankin, and Burnett’s (1996) Inventory of Specific Relationship Standards (ISRS) assesses an individual’s personal standards concerning major relationship themes, including the nature of boundaries between partners (autonomy versus sharing), distribution of control (equal versus skewed) and partners’ levels of instrumental and expressive investment in their relationship, as the individual applies the standards to his or her own 250 Frank M. Dattilio relationship. Furthermore, each standard is assessed within twelve major areas of relationship functioning, such as leisure activities, career and job issues, household tasks and management, and affection. The respondent is asked to indicate his or her belief about how often the couple should act according to each standard, whether or not he or she is satisfied with how the standard is being met in their relationship, and how upset he or she becomes when the standard is not met. Baucom et al. (1996) found that high “relationship-oriented” standards (i.e., focused on minimal or diffuse boundaries between partners, shared control, and high investment) were associated with higher relationship satisfaction. Another key finding was that individuals who were satisfied with (i.e., accepted) the ways in which their standards were met were happier in their relationships. The breadth of the ISRS makes it a useful clinical screening instrument. Although the ISRS has been validated only with couples, it seems reasonable that similar types of items could be useful for assessing boundary, investment, and control standards in parent–child relationships. The Family Beliefs Inventory (FBI) (Vincent-Roehling & Robin, 1986) assesses ten potentially unrealistic beliefs that parents and adolescents maintain about their relationships, and which are likely to contribute to parent–adolescent conflict. Respondents read vignettes describing areas of conflict (e.g., choice of friends, spending time away from home) and then indicate their degree of agreement or disagreement with each of several beliefs. The parents’ version of the FBI includes subscales assessing beliefs concerning (a) ruination (by engaging in a proscribed behaviour, the adolescent will ruin his or her life, or cause harm to the family), (b) perfectionism (the child should behave in a perfect manner), (c) approval/love (family members who love each other confide in each other and always approve of each other’s behaviour), (d) obedience (teenagers should never challenge parental rules or opinions), (e) self-blame (a child’s misbehaviour is due to poor parenting), and (f) malicious intent (the adolescent’s misbehaviour is intended to upset or punish the parents). The adolescent’s version includes subscales for (a) ruination (parental restrictions will ruin the child’s life), (b) autonomy (teenagers should have as much freedom as they want), (c) approval/love (loving parents should always approve of their children’s behaviour), and (d) unfairness (parents should never treat their children in ways that adolescents consider unfair). The FBI is based on the premise that extreme beliefs exacerbate conflict in parent–child interactions, and that identifying such beliefs helps therapists design cognitive interventions for developing more collaborative and constructive problem-solving among family members. Although all of the cognitions assessed by the FBI are referred to as beliefs, within Baucom et al.’s (1989) taxonomy, it appears that perfectionism, unfairness, approval/love, obedience, and autonomy are standards, malicious intent and self-blame are attributions, and ruination is an expectancy. Several attribution scales have been developed for use in clinical research, and these can be applied in clinical practice as well. Pretzer, Epstein, and Techniques and strategies with couples and families 251 Fleming’s (1991) Marital Attitude Survey (MAS) includes subscales assessing attributions for relationship problems to one’s own behaviour, one’s own personality, the partner’s behaviour, the partner’s personality, the partner’s lack of love, and the partner’s malicious intent. Fincham and Bradbury’s (1992) Relationship Attribution Measure (RAM) asks the respondent to rate his or her agreement with statements reflecting attributions about ten hypothetical negative partner behaviours (e.g., “Your husband/wife criticises something you say”). Three statements assess the degree to which the cause of the problem is viewed as residing in the person’s partner, is stable versus unstable, and affects other areas of the relationship in a global way versus being specific to the one problem area. Three items assess “responsibility” attributions, including intentionality, selfish motivation, and blameworthiness. Fincham and Bradbury chose hypothetical situations for the RAM because they provide a standardised measure across individuals and because previous studies indicated that couples make similar attributions about hypothetical and real relationship events. Baucom, Epstein, Daiuto, Carels, Rankin, and Burnett (1996) developed a Relationship Attribution Questionnaire with which the respondent rates causal and responsibility attributions for real problems in his or her relationship, as well as the degrees to which the problems are attributed to boundary, control and investment factors similar to those assessed in relationship standards by the ISRS. Numerous other self-report questionnaires have been developed to assess aspects of parent–child relationships and general family functioning, and excellent reviews of these measures can be found in texts by Grotevant and Carlson (1989), Touliatos, Perlmutter, and Straus (1990), and Jacob and Tennenbaum (1988). Some instruments, such as the Family Environment Scale (Moos & Moos, 1986), the McMaster Family Assessment Device (Epstein, Baldwin, & Bishop, 1983), and the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales III (Olson, Portner, & Lavee, 1985) assess family members’ global perceptions of family characteristics such as cohesion, problem-solving, communication quality, role clarity, emotional expression, and values. Other scales, such as the Family Inventory of Life Events and Changes (McCubbin, Patterson, & Wilson, 1985) and the Family CrisisOriented Personal Evaluation Scales (McCubbin, Larsen, & Olson, 1985) provide more specialised assessment of family functioning (e.g., members’ perceptions of particular stressors and family coping strategies). Because family of origin is also an important aspect of the cognitive-behavioural approach, the Family-of-Origin Scale (FOS) (Hovestadt, Anderson, Piercy, Cochran, & Fine, 1985) is an excellent tool to measure the self-perceived levels of health in one’s family of origin. In general, these scales do not provide data about specific cognitive, behavioural, and affective variables central to a cognitive-behavioural assessment, but they do tap a variety of important components of family functioning likely to be of interest to all family therapists. A few instruments tap family members’ attitudes about parenting roles 252 Frank M. Dattilio and thus are more directly relevant to cognitive assessment. For example, the Parental Authority Questionnaire (Buri, 1991) assesses parental authority or disciplinary practices from the point of view of the children. This measure allows clinicians to better understand the cognitions of the offspring and how they view their parents. Interview assessment of cognitions Clinical interviews with members of a couple or family, together or individually, provide the opportunity to elicit idiosyncratic cognitions and to track inferential processes that cannot be assessed by standardised questionnaires. Using Socratic questioning methods that are the hallmark of cognitive therapy (Beck, 1995; Beck et al., 1979), the clinician inquires about the chains of thoughts that [often] mediate between events in the relationship and the individual’s emotional and behavioural responses. Beck et al. (1979) developed the “downward arrow technique” to identify the underlying schemata (e.g., assumptions and standards) beneath an individual’s automatic thoughts. This is explained earlier in this chapter. In addition, the therapist also needs to collaborate with both partners to gather information for testing the validity of spouses’ or family members’ attributions and expectancies. The goals of the treatment plan will depend on how much of their inferences about each other’s actions reflect real negative motives versus cognitive distortions. The clinician usually attempts to gather information about spouses’ or family members’ cognitions as they occur during family interactions, rather than relying on the clients’ retrospective accounts about what they might have been thinking about each other. The therapist can look for behavioural cues of individuals’ emotional responses as the couple or family interacts during sessions and can interrupt them selectively in order to inquire about the emotions and any associated cognitions. Family members also can be given forms for recording distressing events between sessions, with instructions to write details about the situation, their cognitions, their emotions, and their behavioural responses to each other (see Baucom and Epstein’s 1990 text for details). Assessment of couple and family behavioural interactions Given the consistent evidence that exchanges of negative behaviour among family members are associated with relationship distress, traditional behavioural marital and family therapy methods of assessment and modification of behavioural interactions remain an important component of a cognitivebehavioural approach. However, there is empirical evidence that members of distressed couples often behave in more positive ways with people other than their partners (e.g., Vincent, Weiss, & Birchler, 1975), and an important question to be answered is whether a family’s excesses of negative exchanges or Techniques and strategies with couples and families 253 deficits in positive exchanges are due to skill deficits or other factors. For example, some individuals readily report that their communication with coworkers, friends, and other people is more positive than with their family members. At times, when the therapist conducts a careful inquiry about the sequence of internal and external events leading up to an aversive exchange, it becomes clear that the process of “sentiment override” (Weiss, 1980) is operating, wherein the pre-existing general sentiment that an individual experiences toward a family member influences the affective and behavioural responses to that person’s current behaviour more than the objective qualities of the person’s behaviour. Thus, if an individual has developed general negative emotions and attitudes toward a relative based on their past interactions, this general negative sentiment may lead the individual to feel irritated toward that person in present situations when the relative is attempting to behave in positive ways (and may be judged to be behaving positively by a therapist or other outside observer). Therefore, when assessing a family’s exchanges of positive and negative behaviour, it is important to gather information about situation-specificity of any negative interactions. The basic question to be answered is the degree to which the negative interactions have generalised over time and settings. For example, when asked systematically for details, many couples and families report that there have been times in the past when they have behaved more positively; or, they may report instances in which they have behaved more positively with other people. The clinician can conduct a “functional analysis”, collecting information about antecedent events/conditions and consequences that are associated with more positive and less negative behaviour. Evidence that negative behaviours are less likely to occur under particular circumstances suggests that family members possess constructive skills that are elicited by certain conditions but not by others. The fact that each member of a couple or family uses good communication skills when talking with the therapist often provides this sort of data. The therapist can point to such contrasting behaviour when providing a rationale to the family for exploring changes in their relationships that could create conditions more likely to elicit the types of positive behaviour that they direct toward therapists and other people. Some aspects of the more favourable conditions may involve physical qualities of the setting (e.g., the absence of daily stressors such as interruptions from ringing telephones and distractions such as television), and other aspects may involve different cognitive sets concerning situations (e.g., a belief that it is impolite to criticise strangers, but it is one’s right to be less guarded and to exercise uncensored expression at all times with one’s intimates). A third aspect of conditions more favourable to positive communication may be the existence of more positive “sentiment” toward other people than toward one’s family members, as noted above. Thus, the assessment of a couple’s or family’s behavioural interactions includes collecting information about the frequencies and reciprocal patterns 254 Frank M. Dattilio of positive and negative behaviours that the individuals exchange, situational variations in those behaviours, and any non-behavioural factors (cognitions and emotions) that influence the behavioural variations. Behavioural assessment typically includes both self-report questionnaires administered to the family members and some form of behavioural observation conducted by the therapist. Behavioural observation Because of the limitations of self-report assessments, it is important for the clinician to observe samples of a family’s interactions directly. A common misconception about behaviour therapy is that it is a “technology of techniques”. Actually, one of behaviour therapy’s essential ingredients is careful and detailed observation of behaviour and its consequences. Opportunities for behavioural observation exist from the first moment that a couple or family enters the therapist’s office, and experienced family therapists become adept at noticing the process of verbal and nonverbal behaviours that occur among the family members as they talk to the therapist and to each other. Although the topics (content) of family discussions are important (and are foci of cognitive assessment and intervention), the goal of systematic behavioural observation is to identify specific acts by each individual, and the sequences of acts among family members, that are constructive and pleasing or destructive and aversive. The observation of family interactions can vary according to (a) the amount of structure the clinician imposes on the interaction and (b) the amount of structure in the clinician’s observational criteria or coding system. Even though a family’s behaviour in the therapist’s office is likely to differ to some degree from their typical interactions at home, many families reveal significant patterns when given an opportunity to talk about issues in their relationship with minimal intervention by the therapist. We have found that as couples and families become more comfortable with the office setting and with our presence, they tend to focus their attention on each other and respond more spontaneously to each other. If the therapist “fades into the background” for a while, he or she can observe the behavioural interactions. The goal of imposing little structure on the interaction is to sample the couple’s or family’s communication in as naturalistic a way as possible in the office setting. This can sometimes be achieved through specific homework assignments (Dattilio, in press). In contrast to relatively unstructured couple interactions, the clinician can provide a family with specific topics for their discussions and even a goal, such as trying to understand each other’s thoughts and feelings, or to resolve a particular relationship problem. For example, one can ask each member of a couple to complete an inventory, such as Spanier’s (1976) Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS), with which they rate the degree to which there is Techniques and strategies with couples and families 255 conflict in their relationship in each of several areas (e.g., demonstration of affection, household tasks, amount of time spent together). The clinician then selects a topic for which both partners reported at least moderate disagreement and asks the couple to spend ten minutes trying to resolve their conflict. Similarly, parents and adolescents can be given a topic that they identified as a source of conflict on the Issues Checklist (Robin & Foster, 1989) and asked either to discuss their feelings about the issue or to try to find a solution to the issue. Often it is only when a couple or family has been instructed to engage in a problem-solving discussion that the clinician is able to identify a specific difficulty that they have with this specialised form of communication. This is similar to the “enactment” that Minuchin and Fishman use with their structural family therapy. A difference, however, is that cognitive-behaviour therapists may be more directive in this process than the structural family therapist. For example, some clients fail to define a problem in specific behavioural terms, which handicaps them when they attempt to generate a feasible solution. Others fail to evaluate advantages and disadvantages of a proposed solution, and subsequently become discouraged when they try to carry out the solution and encounter unanticipated obstacles or drawbacks. By observing the clients’ discussion in the therapy session, the clinician can identify the specific problematic behaviours and can plan interventions to improve their problem-solving skills. The clinician’s own observational criteria for assessing a couple’s interactions can vary in detail and structure as well. On the one hand, the clinician can begin the observation with no predetermined categories of behaviour to focus on, and can look for repetitive patterns that appear to play roles in a couple’s presenting complaints. Using the basic principle of functional analysis, the clinician observes antecedent events and consequences that may be controlling the occurrence of each partner’s negative behaviour. For example, a husband may have complained that his wife rarely reveals or talks about her feelings, but the clinician may observe that whenever the wife does express her feelings, the husband turns away. Similarly, circular causal processes in couple interaction can be observed, as when a clinician identifies how one partner’s tendency to pursue tends to prompt the other’s withdrawal, and vice versa. Techniques in therapy Identifying cognitive distortions and labelling them Because cognitive distortions are an integral part of the therapy process, it is essential that the couple learn not only to recognise them, but also to identify them readily. An essential part of treatment then is for the therapist to make sure the couple understand this clearly. One exercise is to have each partner keep a log of negative thoughts during the week and label any distortions in those thoughts. This log should be reviewed by the individual and the therapist 256 Frank M. Dattilio until the individual can do this exercise successfully. This will be important later when it will be necessary for the therapist to rely on the couple’s ability to recognise and identify distortions. When the couple come in for their sessions, the log of negative thoughts should be reviewed with both partners identifying the distortions described below. Identifying cognitive distortions involves a type of self-monitoring that is imperative in cognitive therapy for restructuring thought processes. The same cognitive distortions that were identified in early writings on cognitive therapy as contributing to depression (Beck, et al., 1979) are also sources of relationship discord. Below is a list of ten of the most common cognitive distortions made by couples: 1 Arbitrary inference. Conclusions are made in the absence of supporting substantiating evidence. For example, a man whose wife arrives home a half-hour late from work concludes, “She must be having an affair.” 2 Selective abstraction. Information is taken out of context; certain details are highlighted while other important information is ignored. For example, a woman whose husband fails to answer her greeting the first thing in the morning concludes, “He must be angry at me again.” 3 Overgeneralisation. An isolated incident or two is allowed to serve as a representation of similar situations everywhere, related or unrelated. For example, after being stood up for an initial date, a young woman concludes, “All men are alike. They’re insensitive!” 4 Magnification and minimisation. A case or circumstance is perceived in greater or lesser light than is appropriate. For example, an angry husband “blows his top” upon discovering that his wife has overspent the budgeted amount for groceries and catastrophises, “We’re doomed financially.” 5 Personalisation. External events are attributed to oneself when insufficient evidence exists to render a conclusion. For example, a woman finds her husband remaking the bed after she previously spent time making it herself concludes, “He is dissatisfied with my housekeeping.” 6 Dichotomous thinking. Experiences are codified as either all or nothing, a complete success or a total failure. This is otherwise known as “polarised thinking”. For example, a wife who states to her husband as he paints the living room, “I wonder whether a lighter shade would have been nicer,” elicits the reaction from her husband, “She’s never happy with anything.” 7 Labelling and mislabelling. Imperfections and mistakes made in the past are allowed to define one’s self. For example, subsequent to making repeated errors in balancing the chequebook, a partner states, “I am really stupid,” as opposed to recognising the errors as being human. 8 Tunnel vision. Sometimes partners see only what they want to see or what fits their current state of mind. A man who believes that his lover is totally self-centred may accuse him of making all choices based on purely selfish motives. Techniques and strategies with couples and families 257 9 Biased explanations. This is an almost suspicious type of thinking that partners develop during times of distress, during which there is an automatic assumption that their mate holds a negative ulterior motive for actions. For example; a woman states to herself, “He’s acting real `loveydovey’ because he’ll later probably want me to do something that he knows I hate to do.” 10 Mind reading. This is the magical gift of being able to know what the other is thinking without the aid of verbal communication. Couples end up ascribing negative intentions to their partners. For example; a woman says to herself, “I know what Dimitri is going to say when he sees what I spent on this suit.” These distortions have been found to occur frequently among couples in distress and, in fact, may occur in most relationships at one time or another. Couples are made aware of these common distortions and are then instructed to identify where their own thinking may fit with these distortions. Each time a person experiences an automatic thought about his or her partner and identifies it as a negative or dysfunctional thought, he or she then attempts to label it as an instance of one of the aforementioned distortions. When couples learn to assign a label to their cognitive distortions, they are then able to set the stage for re-evaluating the structure of their thinking. It should be made clear at this point that the expertise of the clinician is important in determining whether or not additional psychopathology is evident in an individual’s thought process. If not detected during the assessment phase, any disorder in thinking, behaviour, or affect may clearly manifest itself here. Should this be the case, alternative types of treatment may need to be considered. Depending on whether or not the problem is severe, couples therapy may or may not be continued. When there are no severe interfering problems, such as a formal thought disorder, the partners are instructed to keep track of their automatic thoughts and begin to identify the distortions by labelling them. The following is an example: Automatic thoughts and cognitive distortions Automatic thought “My wife should know by now that I hate to be interrupted while I am reading the paper.” Automatic thought “It’s too late to do anything about this marriage.” “My husband is well beyond change.” Label Mind reading Label Magnification 258 Frank M. Dattilio The purpose of these exercises is to aid the couple to recognise that their thinking may be distorted due to insufficient information and to help them monitor the kind and frequency of distortions they use. This conscious monitoring of their thoughts and distortions enables them to become more aware of how their thinking affects their partner and themselves. Faulty information processing Cognitive theorists believe dysfunctional thinking and distortions develop from faulty information processing. It is thought that individuals learn maladaptive ways of processing information as a result of early environment and experience, as well as by a biological tendency to categorise and group observations. These processes involve perceptions of, and inferences made from, certain stimuli. The stereotypic scenario of a woman who is afraid of a mouse illustrates this process. Every time she comes in contact with a mouse, regardless of its size, the cartoon depiction of a woman begins to scream irrationally and climbs for the highest ground. Her underlying belief or schema is that mice are something to be fearful of. If questioned, she might say she is uncertain as to exactly why, but it is something that she has been raised to believe; she almost instinctively fears mice. If pressed, she may disclose to you that she has learned through a parent that mice are dirty or contaminated with germs. Yet, this still leaves insufficient information to support such an exaggerated fear reaction. This is an example of a belief that is supported by insufficient or faulty information – a distorted belief that is devoid of substantiating information. Negative framing It is interesting to note that the complaints of couples during the intake phase often include particular characteristics of their partners that are the inverse, negative side of those characteristics that once attracted them to their partner (Abrahms & Spring, 1989). For example, in the case of Ana and Tomas, Ana stated that the characteristics of Tomas that she finds to be most intolerable are that he is lazy, demanding, picky and absent-minded. Ironically, when asked later for some of the characteristics that originally attracted Ana to Tomas, she listed the following adjectives: laid-back, knows his expectations of others, precise, and carefree. When these characteristics were listed juxtaposed on paper, Ana could clearly see that her negative impressions of Tomas were merely the negative aspects of traits she was originally attracted to. Techniques and strategies with couples and families 259 Initial redeeming qualities about Tomas Easy-going Knows his expectations of others Meticulous Carefree Amorous —— Current irritating qualities about Tomas Lazy —— —— —— —— Demanding Picky Absent-minded Always wants sex Outlining this concept for couples directly in the session serves as a powerful tool to help them begin to understand negative framing and how the negative frame itself is often merely a distortion of what were once considered attractive qualities and have been transformed over time in the partner’s mind to be negative attributes. This perspective often gives individuals some hope, and it also encourages them to investigate their distortions. More importantly, they can begin to change their perceptions by questioning and weighing the evidence for their thinking. Once couples accept the concept of negative framing, it reinforces the cognitive model. This technique is used with both partners, preferably during a conjoint session. Alternatively, it might be constructed during an individual session, and then reviewed during a conjoint session with an emphasis on demonstrating for the spouse the process of restructuring the negative frame to a more positive frame. Teaching couples to identify automatic thoughts The crux of the cognitive model is the identification of partners’ automatic thoughts about themselves and, most importantly, about the relationship. Once again, automatic thoughts are defined as thoughts which occur spontaneously in the individual’s mind about certain life circumstances or individuals in the environment. These automatic thoughts may be either negative or positive; however, in most conflictual situations, they are negative. Some of the most common negative automatic thoughts include: • • • • “If he loved me, then he would agree with me.” “She only cares about her own interests.” “The relationship is hopeless.” “Nothing I do is right.” When couples learn to observe their thinking style and their patterns of thought, they develop the skill of identifying automatic thoughts that spontaneously flash through their minds. These are the cognitions that can trigger charged emotional responses and actions that often result in conflict. 260 Frank M. Dattilio Since many of these automatic thoughts arise from underlying beliefs or schemata that have developed slowly over time, they are corrected and restructured over time through the use of identification and practice. In lay terms, such identification allows individuals to “think about what they are telling themselves” about the situation or circumstance and learn new or alternative ways of processing what they perceive. In order to improve the skill of identifying automatic thoughts, clients are typically instructed to keep a pad or notebook handy and to jot down a brief description of the circumstances surrounding a conflict period. Included in this notation should be a description of the situation, the automatic thought that came to mind, and the resulting emotional response. A modified version of the “Daily Dysfunctional Thought Record” (Center for Cognitive Therapy, Philadelphia) may be used for this purpose. Below is an example of excerpts extrapolated from clients’ notebooks: Relevant situation/event Automatic thought Emotional response “John came home and started to recut the chicken parts that I had previously cut for dinner without saying a word to me.” “The way I cut them wasn’t good enough for John.” Frustration “I can’t do anything right.” Dejected Relevant situation/event Automatic thought Emotional response “Maria failed to take the dog out for a walk again last night.” “She really expects me to do her job.” “She couldn’t be bothered to stoop to such a menial task.” Resentful Anger/Vindictive Through this type of record keeping, the therapist is able to demonstrate to the couple how their automatic thoughts are linked to emotional responses and how this contributes to their negative frame concerning their partner. Linking emotions with automatic thoughts Once spouses have learned to identify automatic thoughts accurately, more emphasis is placed on linking thoughts to emotional responses. This is important because it has been found that, very often, impulsive behaviours that create damage in relationships occur as a result of charged emotions. In addition, spouses will often chalk up certain experiences or situations as a result of “just how I feel,” disowning any responsibility for being able to Techniques and strategies with couples and families 261 influence how they feel. For example, one husband stated that he failed to see the point of trying to work out his marital problems because he simply did not feel emotion for his wife anymore. This response can be linked to certain automatic thoughts that may explain more clearly why his feeling is blunted. An exercise that often proves quite useful for couples is to have them review their log books and indicate the links between thought and emotion. Then they use a method of alternative responding or thought correction to effect emotional change. The use of imagery and role play techniques When identifying their automatic thoughts and underlying beliefs, couples may sometimes have difficulty recalling pertinent information regarding conflict areas, particularly during emotionally charged situations. Imagery and/or role play techniques may be extremely helpful in jogging memories regarding such situations. In addition, these techniques may also be useful in helping partners revive their positive feelings about one another. The use of fantasy recollection to revive old affection toward one another during dating periods may help couples see that those feelings were there at one time and may be regenerated depending on their efforts in working on the relationship. Therapists can utilise these cognitive-behavioural techniques throughout therapy. They may be useful in the early stages of therapy, when one or both partners are claiming they cannot recall happier times. The therapist may suggest to one or both (in a conjoint visit or individually) to focus on past scenes or images, such as early anniversaries, birthdays, their wedding day, dating periods, and so forth. This imagery session may be more successful if the therapist has the individuals recall specifically on what they or their partner were wearing at the time, what the room was like that they were in, specific recollection of other people who were present, and so on. Details such as these may serve to jog memories of old feelings. These exercises are meant to serve as primers of motivation to rekindle positive feelings, or feelings believed to be lost. Once the therapist is able to facilitate the recreation of a positive image of each other, the couple can begin to link emotions and positive automatic thoughts to those images. Imagery techniques are certainly not for everyone and may even backfire at times, depending on the individual. Therefore, they should be used with caution. Role play techniques are also used to flush out feelings or thoughts, particularly in those couples who are non-communicative in therapy or treatment sessions. The therapist should use discretion in determining when these techniques are appropriate (Dattilio & Padesky, 1990). 262 Frank M. Dattilio Dispelling automatic thoughts and reframing/testing automatic thoughts The process of restructuring automatic thoughts involves considering alternative explanations and adopting them as part of the individual’s cognitive repertoire. In order to accomplish this, the dysfunctional automatic thought has to be tested by the client. Once this is accomplished, a reframing of perception occurs which may allow the client to view his or her partner or situation in a different light. An example of this is a woman who developed the belief that her husband was no longer in love with her as a result of his withdrawal. Her thoughts occurred in the following sequence: Automatic thought 1. “Alex has been increasingly withdrawn from me over the past week and a half. This has to mean something about our relationship.” Emotion Worried Cognitive distortion Personalization 2. “I am wondering if he has another woman in his life.” Sad/worried, depressed Mind reading Arbitrary inference In the example above, automatic thought 1 is accompanied by an emotion of worry and is an example of personalisation because she interprets Alex’s behaviour as relating only to herself. In fact, it is possible he may be withdrawing from everyone. She then draws an arbitrary inference from what she observes and makes a global negative statement, “He doesn’t love me anymore.” The next step is to ask her to test her thoughts by weighing the existing evidence and considering alternative explanations. For example: What evidence exists to substantiate this thought? Might there be an alternative explanation for this behaviour? 1. “He doesn’t appear to be excited to see me when I come home.” 1. “Perhaps something else is bothering him. Work or finances or maybe a midlife crisis.” 2. “He is less amorous than he used to be with me.” 2. “He might just need some space from me right now – time to breathe.” By weighing the evidence that exists and seeing that it actually is insufficient to draw any strong conclusion, the individual is able to consider an Techniques and strategies with couples and families 263 alternative explanation. This will very likely reduce her negative frame until she has the opportunity to gather additional data. She can collect additional data by observing for a longer period of time or inquiring, in a nonthreatening manner, what may be causing him to withdraw. The latter, of course, may also require communication training for both spouses. This exercise will at least help set the tone for her approach, making her inquiry to him much less accusatory. Rating the alternative explanation for alternative response Individuals should next be asked to rate the credibility of the alternative explanation. This is important because it may not become assimilated as a new part of their thinking unless they place some degree of belief in it. For example, with the woman in the previous scenario, on a scale of 0%–100%, she rated her alternative beliefs 50%. Over time, the therapist should look for an improvement in the rating of the belief if new evidence supports it. The use of evidence in correcting distorted thinking As mentioned previously, when restructuring thought processes and underlying beliefs, it is essential to help the individual learn to rely on evidence to support the correction of distorted thoughts. It is the collection of evidence that allows an individual to weigh contrasting information against the schemata that are being used to formulate the individual’s current thoughts and beliefs. Since most distorted thoughts come from faulty or erroneous information, then it stands that new, competing evidence is required to test and change existing thoughts. Gathering and weighing the evidence for one’s thought are an integral part of cognitive therapy. Weighing the evidence and testing predictions Weighing the evidence is actually a skill which needs to be developed over time. Just as a prosecuting attorney or a forensic pathologist needs to carefully weigh each piece of evidence prior to rendering an opinion or gathering more data, each partner must act in a similar manner. By spending time to review each piece of information, the individual has leisure to consider carefully its validity. Writing this reasoning process down is especially helpful for the individual to see what actually is known. The other side of restructuring is testing predictions. When the evidence appears insufficient, it is often a good idea to formulate a hypothesis, think about what might occur in any given situation, and test the prediction. This is another form of gathering data. For example, suppose a woman who feared 264 Frank M. Dattilio rejection by her husband because she overdrew their checking account tested her prediction to see if her husband would actually reject her. She could intentionally question him about her fear and gather hard-core evidence in order to evaluate her thoughts and decide whether or not they were viable. Testing predictions is another means of dispelling dysfunctional thoughts. Practising alternative explanations Couples thus learn to defend themselves against distorted thinking by information gathering and practising their new thoughts daily. With repeated practice, couples can learn to restructure their thinking and balance out the distortions denied from faulty information. The therapist can then have couples practice these alternative responses and explanations as homework assignments until they are assimilated as a regular part of their thought processes. Reframing – considering the negatives in a positive light Reframing involves taking all of the data gathered, weighing the evidence, and developing alternative explanations and a new view of the partner. This then replaces the negative frame once held by the client. Another way to accomplish this change is to view the negative attributes in a positive light. This should not be confused with “the power of positive thinking.” Since it involves weighing actual evidence, it is instead a more systematic and confirmative way of viewing people or situations in a different and more realistic light. It is also something that does not happen overnight; couples should be cautioned to expect gradual change. The therapist teaches couples to integrate all of the newly gathered data and practice viewing it cohesively. This is demonstrated in the example in Figure 10.2. Increasing positives in the relationship In addition to cognitive interventions, cognitive therapy emphasises behavioural change. Behavioural homework assignments may be given to couples at any point in treatment to improve the quality of the relationship, strengthen new skills, or test the validity of beliefs as described previously. This type of behavioural assignment was first described in detail by Stuart (1980) as “Caring Days”. Techniques and strategies with families Cognitive-behaviour family therapy is virtually in its infancy, with almost no reference to empirical outcome studies present in the literature as of this Automatic thought After confronting John about his actions he stated that he felt that it would be a nice gesture to start helping me with dinner preparations without me having to ask him. I may have jumped the gun! Maybe he didn’t realise that I had already cut up the chicken to completion – or maybe he just wanted to help! Maybe he was trying to subtly state that he was displeased! I had better ask him about his reasons for cutting it, so I get a more clearer idea. Figure 10.2 Reframing. Gather more evidence (reframe) Hypothesis/prediction John came home and started The way that I cut them recutting the chicken parts that wasn’t good enough for him. I had previously cut for dinner without saying a word to me. I can’t do anything that satisfies him. Situation Could he have just been trying to help? Is it enough for me to assume that his cutting the chicken parts automatically means that he is so displeased with what I do? Weigh and question the evidence I did jump the gun.This I rate this belief 80% was actually a very nice credible. gesture. One in fact that I have been requesting of him for years. Relieved – more appreciative. Still guarded somewhat, because John has changed other things that I have done in the past. However, if I check out my inferences with him each time in the future, we should have a better understanding between us. Rate the degree of Emotional Response belief (%) for the revised cognition All or nothing thinking Dejected Alternative response Mind reading Cognitive distortion Frustration Emotional response Techniques and strategies with couples and families 265 266 Frank M. Dattilio writing (Alexander, 1988; Epstein, Schlesinger & Dryden, 1988; Teichman, 1992; Dattilio, 1994, 1996b, 1997, 1998, 2001; Schwebel & Fine, 1994). As is the case with couples therapy, cognitive-behaviour therapy with families developed out of behavioural marital theory, which had its inception in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Several single case studies were published involving family interventions in treating children, in which family members were recognised as highly influential factors in the child’s natural environment (Faloon, 1991). It was not until later that a more comprehensive style of intervention with the family unit was implemented with families in distress. (Patterson, McNeal, Hawkins, & Phelps, 1967; Patterson, 1971). Since that time, applications of behavioural therapy to family systems have become more visible in the professional literature, with an emphasis on contingency contracting and negotiative strategies (Gordon & Davidson, 1981; Jacobson & Margolin, 1979; Liberman, 1970). The cognitive-behavioural approach to families applies many of the aforementioned strategies with couples in an expanded model in order to address family schemata, or members’ beliefs about each other. Therapists also look at family constructs that are jointly used to interpret the world and circumstances in their environment (Teichman, 1992; Dattilio, 1994, 1998, 2001). This is underscored by the philosophy that family members’ behaviours toward each other will not change unless their specific views or frames of each other change (Barton & Alexander, 1981). The focus of the cognitive-behavioural theory in family therapy is basically twofold: (1) It serves to explain family members’ expectations of one another and how they affect multiple interactions within the family context; and (2) it considers the impact that all of this has on the family’s ability to cope with crises, change, and other unexpected life events. This twofold focus constitutes much of the premise on which behavioural family therapy is based (Faloon, 1991) with an increased emphasis on styles of thinking. Epstein, Schlesinger, and Dryden (1988) suggest that in applying this concept to distress in family relationships, the particular combination of emotions that each family member feels regarding each other member is determined by the specific content of his or her perceptions of the nature of the interactions between the self and the other person (p. 6). The specific content of a family member’s perception of his or her interaction with other family members affects both the quality and intensity of emotional distress as well as behavioural responses toward other members, and serves to shape their attributions. These attributions are believed to develop initially not only by family interaction, but also by cognitions that then exacerbate dysfunctional interaction (Fincham, Beach, & Nelson, 1987). The basic tenet of cognitive family therapy contends that individual family members maintain beliefs or schemata about every other member of the family unit in addition to possessing a conceptualisation of family interaction in general. These schemata are conscious and are overtly expressed during Techniques and strategies with couples and families 267 day-to-day interactions. They develop as a result of the schema that each spouse in the relationship brings from the family of origin, which then becomes modified to fit into a relationship as spouses begin to function as a dyad. This dyad is further modified with the birth of offspring and the development of a triad or family unit. Here the development of triangles becomes important, since they contribute profoundly to the development of family members’ cognitions (Procter, 1985). This aspect of cognitive-behaviour family therapy is clearly borrowed from systems theory and is integrated with the basic tenets of the cognitive-behavioural approach. Each one of these belief systems also contributes to jointly held beliefs that form as a result of years of integrated interaction among family members which is identified as a “family schema” (Dattilio, 1994, 1997, 1998). These beliefs also involve distortions which serve to contribute to faulty perception of family members and result in dysfunctional interaction. Just as the basic cognitive-behavioural techniques are applied to the management of depression and other emotional disorders, they are also applied to couples and families in changing dysfunctional interactional patterns. Therefore, cognitive restructuring procedures are also used in helping family members test the validity of their own thoughts about family interactions. Emphasis is placed on encouraging family members to become conscientious observers of their own interpretations and evaluations of family transactions. Hence, the therapist works directly in the family unit, having each member test the validity of his or her attributions, expectancies or schemata about their relationships and about what each perceives regarding each other’s actions. The question asked most frequently by the therapist is, “What is going through your mind right now and what evidence exists to support your beliefs?” In this way, the therapist helps family members test the reality of their thought processes and weigh the evidence that supports them. This allows family members to begin to challenge some of their own behaviours and gain a different perspective on how they may be affecting the family dynamics. Epstein, Schlesinger, and Dryden (1988) emphasise the notion of counteracting the feedback loops that serve to reinforce dysfunctional thinking by working conjointly with individual family members to track ongoing interactions and identify sources of feedback that strengthen a member’s negative expectancy, attribution or belief (p. 36). This is done by making family members confront each other and challenge distorted thoughts in a constructive manner that provides them with alternative information. Individual members are instructed to process their automatic thoughts in the same fashion that couples are, as illustrated in Figure 10.2. Since destructive interaction is so much a common occurrence in dysfunctional families, such techniques as “self-instructional training” are used in providing them with covert instructions for controlling impulsive reactions toward one another. This technique is borrowed from Meichenbaum’s (1977) 268 Frank M. Dattilio work in stress inoculation. Epstein (1982) also suggests the use of self-instructional training to control aversive exchanges between spouses, which can be also applied within the family constellation. In addition to cognitive restructuring techniques, cognitive-behaviour therapy utilises several behavioural interventions such as assertiveness training, behaviour-exchange procedures, communication training and problem-solving techniques (Dattilio, Epstein, & Baucom, 1998). The specific use of these interventions in conjunction with cognitive techniques depends on the assessment of the family needs, which the therapist assesses in a collaborative fashion during the intake and as therapy proceeds. Compatibility of cognitive-behaviour therapy as an integrative model Several components of cognitive-behaviour therapy appear highly adaptable to other modalities of marital and family intervention (Dattilio, 1998). For one, the use of communications training and problem-solving is one aspect found within the systems domain as well as in other approaches. Secondly, the notion of identifying core beliefs and patterns of thought may blend nicely with other approaches, as the focus involves changing interactional patterns among couples and family members and dealing with issues of rule-guided behaviour and problem-solving strategies. A comprehensive exploration of the integrability of cognitive therapy is illustrated by numerous case examples in an edited volume by Dattilio (1998). Even those approaches that appear to be the most antithetical to cognitive therapy show some compatibility to its integration. Hence, cognitive therapy combined with behavioural techniques appears to have much to offer other modalities of treatment and, if implemented carefully, may serve to broaden the scope of other modalities and techniques and increase the effectiveness of treatment. Behavioural interventions Because of space limitations, only an overview of the major forms of behavioural intervention in cognitive-behavioural couples and family therapy will be provided. More detailed descriptions of therapeutic procedures can be found in texts by Baucom and Epstein (1990), Falloon (1991), Jacobson and Margolin (1979), Robin and Foster (1989), Sanders and Dadds (1993), and Stuart (1980). The degree to which any of these interventions is used with a particular couple or family varies considerably, depending on the clients’ needs. The major forms of behavioural intervention are communication training, problem-solving training, and behaviour change agreements designed to increase exchanges of positive behaviours and decrease negative exchanges among family members. In addition, in families characterised by coercive Techniques and strategies with couples and families 269 exchanges between parents and children, training in parenting skills is likely to be appropriate. Communication training The goals of communication training are to increase family members’ skills in expressing their thoughts and emotions clearly, listening to each other’s messages effectively, and sending constructive rather than aversive messages. Central to achieving these goals is training the partners in expressive and listening skills. Guerney’s (1977) educational approach is widely used by couple and family therapists for teaching clients to take turns as expresser and empathic listener, following specific behavioural guidelines. For example, in the expresser role one’s job is to state views as subjective rather than as facts, to include any positive feelings about the listener when expressing criticisms, to use brief, specific descriptions of thoughts and feelings, and to convey empathy for the other person’s feelings as well. In turn, the listener is to try to empathise with the expresser’s thoughts and emotions (even though this need not indicate agreement with the expresser’s ideas) and convey that empathy to the expresser. The listener is to avoid distracting the expresser by asking questions or giving opinions that shift the topic, avoid judging the expresser’s ideas and emotions, and convey understanding of the expresser’s experience by reflecting back (summarising and restating) the key thoughts and emotions expressed. Detailed guidelines for the expresser and empathic listener, as well as procedures for teaching these skills, can be found in Baucom and Epstein (1990) and Guerney (1977). The therapist typically presents instructions about the specific behaviours involved in each type of skill orally and by means of written handouts that the family members can take home. The therapist can model expressive and listening skills or show the clients videotaped samples such as the tape that accompanies Markman, Stanley and Blumberg’s (1994) Fighting for Your Marriage text. The clients then practice the communication skills repeatedly, with the therapist coaching them in following the guidelines. Typically, a therapist asks the couple or family members to begin their practice of the skills with relatively benign topics, so that any strong emotions associated with highly conflictual topics do not produce sentiment override and interfere with the learning process. Once the family members are able to enact expressive and listening skills effectively, they proceed to more difficult topics. In addition to reducing misunderstandings among family members, use of expressive and listening skills reduces the emotional intensity of conflictual discussions, and increases each person’s perception that the others are willing to respect his or her ideas and emotions. Even when family members are expressing negative feelings about each other’s actions, the polite and structured interactions created by the procedures often reduce destructive messages. 270 Frank M. Dattilio Problem-solving training Problem-solving skills constitute a special class of communication that a couple or family can use to identify a specific problem in their relationship that requires a solution, generate a potential solution that is feasible and attractive to both partners, and implement the chosen solution. Problemsolving is cognitive and oriented toward resolving issues, in contrast to the skills described above that focus on emotional and empathic listening. As in teaching expressive and listening skills, cognitive-behavioural therapists use verbal and written instructions, modelling, and behavioural rehearsal with coaching to help family members develop effective problemsolving communication. The major steps involved in problem-solving include (a) achieving a clear, specific definition of the problem, in terms of behaviours that are or are not occurring (and that family members agree is a problem in their relationships); (b) generating one or more specific behavioural solutions to the problem (using a creative “brainstorming” period if necessary), without evaluating one’s own or other family members’ ideas; (c) evaluating each alternative solution that has been proposed, identifying advantages and disadvantages to it, and selecting a solution that appears to be feasible and attractive to all of the involved parties; and (d) agreeing on a trial period for implementing the solution and evaluating its effectiveness. Details on conducting problem-solving training can be found in texts such as Baucom and Epstein (1990) and Robin and Foster (1989). Acknowledgment Portions of this chapter are adopted from the following with permission: Dattilio, F.M., Epstein, N.B., & Baucom, D.H. (1998). In F.M. Dattilio (Ed.), Case Studies in Couple and Family Therapy: Systemic and Cognitive Perspectives. New York: Guilford. References Abrahms, J.L. (1982, November). Inducing a Collaborative Set in Distressed Couples: Nonspecific Therapist Issues in Cognitive Therapy. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Los Angeles, CA. Abrahms, J. L., & Spring, M. (1989). The Flip-Flop Factor. International Cognitive Therapy Newsletter, 5, 7–8. Alexander, P. C. (1988). The Therapeutic Implications of Family Cognitions and Constructs. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 2, 219–236. Alford, B., & Beck, A. T. (1997). The Integrative Power of Cognitive Therapy. New York: Guilford. Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Barton, C., & Alexander, J.F. (1981). Functional Family Therapy. In A.S. Gusman & Techniques and strategies with couples and families 271 D.P. Kniskern (Eds.), Handbook of Family Therapy (pp. 403–443). New York: Brunner/Mazel. Baucom, D.H., & Epstein, N. (1990). Cognitive-Behavioral Marital Therapy. New York: Brunner Mazel. Baucom, D.H., Epstein, N., Daiuto, A.D., Carels, R.A., Rankin, L.A., & Burnett, C.K. (1996). Cognitions in Marriage: The Relationship Between Standards and Attributions. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 209–222. Baucom, D.H., Epstein, N., Rankin, L.A., & Burnett, C.K. (1996). Assessing relationships standards: The Inventory of Specific Relationships Standards. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 72–88. Beck, A.T. (1988). Love is Never Enough. New York: Harper & Row. Beck, A.T. (1991). Cognitive Therapy as the Integrative Therapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 1, 191–198. Beck, A.T., Rush, A.J., Shaw, B.F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press. Buri, J.R. (1991). Parental Authority Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Assessment, 57, 110–119. Dattilio, F.M. (1989). A Guide to Cognitive Marital Therapy. In P.A. Keller & S.R. Heyman (Eds.), Innovations in Clinical Practice: A Source Book (Vol. 8, pp. 27–42). Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Exchange. Dattilio, F.M. (1990a). Cognitive Marital Therapy: A Case Study. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 1, 15–31. Dattilio, F.M. (1990b). Una guida all teràpia di coppia àd orientàsmento cognitivistà. Terapia familiare, 33, (Luglio), 17–34. Dattilio, F.M. (1994). Families in Crisis. In F. M. Dattilio & A. Freeman (Eds.), Cognitive-Behavioral Strategies in Crisis Intervention. New York: Guilford. Dattilio, F.M. (1996a). Videotape: Cognitive Therapy with Couples: Initial Phase of Treatment (56 minutes). Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press. Dattilio, F.M. (1996b). A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach to Family Therapy with Ruth. In G. Corey (Ed.), Case Approaches to Counseling and Psychotherapy, (4th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. Dattilio, F.M. (1997). Family therapy. In R.L. Leahy (Ed.), Practicing Cognitive Therapy: A Guide to Interventions (pp. 409–450). Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, Inc. Dattilio, F.M. (Ed.) (1998). Case Studies in Couples and Family Therapy: Systemic and Cognitive Perspectives. New York: Guilford. Dattilio, F.M. (2001). Cognitive-Behavior Family Therapy: Contemporary Myths and Misconceptions. Contemporary Family Therapy, 23(1). Dattillio, F.M. Homework Assignments in Couple and Family Therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology (In press). Dattilio, F.M. & Epstein, N.B. Reworking Family Schemas. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy (in press). Dattilio, F.M., Epstein, N.B., & Baucom, D.H. (1998). Introduction to CognitiveBehavioral Techniques with Couples and Families. In F.M. Dattilio (Ed.), Case Studies in Couple and Family Therapy: Systemic and Cognitive Perspectives. New York: Guilford. Dattilio, F.M., & Padesky, C. A. (1990). Cognitive Therapy with Couples. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press, Inc. 272 Frank M. Dattilio Doherty, W.J. (1981). Cognitive Processes in Intimate Conflict: 1. Extending Attribution Theory. American Journal of Family Therapy, 9, 5–13. Ellis, A. (1977). The Nature of Disturbed Marital Interactions. In A. Ellis & R. Grieger (Eds.), Handbook of Rational-Emotive Therapy. New York: Springer. Ellis, A., Sichel, J.L., Yeager, R.J., DiMattia, D.J. & DiGiuseppe, R. (1989). RationalEmotive Couples Therapy: Psychology Practitioners Guidebooks. New York: Pergamon. Epstein, N. (1982). Cognitive Therapy with Couples. American Journal of Family Therapy, 10, 5–16. Epstein, N. (1986). Cognitive Marital Therapy: A Multilevel Assessment and Intervention. Journal of Rational-Emotive Therapy, 4, 68–81. Epstein, N. (1992). A Case of Cognitive Therapy with Couples. In A. Freeman & F. M. Dattilio (Eds.), Comprehensive Casebook of Cognitive Therapy. New York: Plenum. Epstein, N., Baldwin, L.M., & Bishop, D. (1983). The McMaster Family Assessment Device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 9, 171–180. Epstein, N., & Baucom, D.H. (1998). Cognitive-Behavior Therapy with Couples. In F. M. Dattilio (Ed.), Case Studies in Couples and Family Therapy: Multiple Perspectives. New York: Guilford. Epstein, N., & Eidelson, R.J. (1981). Unrealistic Beliefs of Clinical Couples: Their Relationship to Expectations, Goals and Satisfaction. American Journal of Family Therapy, 9, 13–22. Epstein, N., Schlesinger, S.E., & Dryden, W. (1988). Concepts and Methods of Cognitive-Behavioral Family Treatment. In N. Epstein, S.E. Schlesinger & W. Dryden (Eds.), Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy with Families. New York: Brunner/Mazel. Faloon, I.R.H. (1991). Behavioral Family Therapy. In A.S. Gurman & D.P. Kniskern (Eds.), Handbook of Family Therapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel. Fincham, F., Beach, S.R.H., & Nelson, G. (1987). Attribution Processes in Distressed and Non-distressed Couples: Causal and Responsibility Attributions for Spouse Behaviors. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 11, 71–86. Fincham, F.D., & Bradbury, T.N. (1992). Assessing Attributions in Marriage: The Relationship Attribution Measure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 457–468. Fincham, F. & O’Leary, D.K. (1983). Casual Inferences for Spouse Behavior in Maritally Distressed and Nondistressed Couples. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 1, 42–57. Gordon, S.B., & Davidson, N. (1981). Behavioral Parenting Training. In A.S. Gurman & D.P. Kniskern (Eds.), Handbook of Family Therapy. (pp. 517–577). New York: Brunner/Mazel. Grotevant, H.D. & Carlson, C.I. (1989). Family Assessment: A Guide to Methods and Measures. New York: Guilford Press. Guerney, B.G., Jr. (1977). Relationship Enhancement. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Hovestadt, A.J., Anderson, W.T., Piercy, E.A., Cochran, S.W., & Fine, M. (1985) Family-of-Origin Scale. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 11, 287–297. Jacob, T. & Tennenbaum, D.L. (1988). Family Assessment: Rationale, Methods, and Future Directions. New York: Plenum Press. Jacobson, N.S. (1991). Behavioral Marital Therapy. In A. S. Gurman & D. P. Kniskern (Eds.), Handbook of Family Therapy (Vol. I). New York: Brunner/Mazel. Techniques and strategies with couples and families 273 Jacobson, N.S., & Margolin, G. (1979). Marital Therapy: Strategies Based on Social Learning and Behavior Exchange Principles. New York: Brunner/Mazel. Liberman, R.P. (1970). Behavioral Approaches to Couple and Family Therapy. American Journal of Ortho-psychiatry, 40, 106–118. Margolin, G., Christensen, A., & Weiss, R. L. (1975). Contracts, Cognition and Change: A Behavioral Approach to Marriage Therapy. Counseling Psychologist, 5, 15–25. Margolin, G., & Weiss. R.L. (1978). Comparative Evaluation of Therapeutic Components Associated with Behavioral Marital Treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46, 1476–1486. Markman, H.J., Stanley, S., & Blumberg, S.L. (1994). Fighting for Your Marriage. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. McCubbin, H.I., Larsen, A., & Olson, D.H. (1985). F-COPES: Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scales. In D.H. Olson, H.I. McCubbin, H.Barnes, A. Larsen, M. Muxen, & M. Wilson (Eds.), Family Inventories (Revised edition). St. Paul: Family Social Sience, University of Minnesota. McCubbin, H.I., Patterson, J.M., & Wilson, L.R. (1985). FILE: Family Inventory of Life Events and Changes. In D.H. Olson, H.I. McCubbin, H. Barnes, A. Larsen, M. Muxen, & M. Wilson (Eds.), Family Inventories (Revised edition). St. Paul: Family Social Sience, University of Minnesota. Meichenbaum, D. (1977). Cognitive-Behavior Modification: An Integrative Approach. New York: Plenum. Minuchin, S. & Fishman, H.C. (1981). Family Therapy Techniques. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Moos, R.H. & Moos, B.S. (1986). Family Environment Scale Manual (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Olson, D. H., Portner, J., & Lavee, Y. (1985). FACES-III Manual. St. Paul: Family Social Science, University of Minnesota. Patterson, G.R. (1971). Families: Applications of Social Learning to Family Life. Champaign, IL: Research Press. Patterson, G.R., & Hops, H. (1972). Coercion, A Game for Two: Intervention Techniques for Marital Conflict. In R.E. Urich & P. Mounjoy (Eds.), The Experimental Analysis of Social Behavior. New York: Appleton. Patterson, G.R., McNeal, S., Hawkins, N. & Phelps, R. (1967). Reprogramming the Social Environment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 8, 181–195. Pretzer, J.L., Epstein, N.B., & Fleming, B. (1991). The Marital Attitude Survey: A Measure of Dysfunctional Attributions and Expectancies. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 5, 131–148. Procter, H. (1985). A Construct Approach to Family Therapy and Systems Intervention. In E. Button (Ed.), Personal Construct Theory & Mental Health (pp. 327–350). Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books. Revenstorf, D. (1984). The Role of Attribution of Marital Distress in Therapy. In K. Hahlwag & N.S. Jacobson (Eds.) Marital Interaction: Analysis and Modification (pp. 309–324). New York: Guildford. Robin, A.L. & Foster, S.L. (1989). Negotiating Parent-Adolescent Conflict: A Behavioral-Family Systems Approach. New York: Guilford Press. Sanders, M.R., & Dadds, M.R. (1993). Behavioral Family Intervention. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. 274 Frank M. Dattilio Schindler, L., & Vollmer, M. (1984). Cognitive Perspectives in Behavioral Marital Therapy: Some Proposals for Bridging Theory, Research and Practice. In K. Hahlwag & N. S. Jacobson (Eds.), Marital Interaction: Analysis and Modification. (pp. 309–324). New York: Guilford. Schwebel, A.I., & Fine, M. A. (1994). Understanding and Helping Families: A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach. Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Spanier, G.B. (1976). Measuring Dyadic Adjustment: New Scales for Assessing the Quality of Marriage and Similar Dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38, 15–28. Stuart, R.B. (1969). Operant-Interpersonal Treatment for Marital Discord. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 33, 675–682. Stuart, R.B. (1976). Operant Interpersonal Treatment for Marital Discord. In D.H.L. Olson (Ed.), Treating Relationships. Lake Mills, IA: Graphic Press. Stuart, R.B. (1980). Helping Couples Change: A Social Learning Approach to Marital Therapy. New York: Guilford. Teichman, Y. (1992). Cognitive Therapy with Families – A Case Study. In A. Freeman & F.M. Dattilio (Eds.), Comprehensive Casebook of Cognitive Therapy. New York: Plenum. Touliatos, J., Perlmutter, B.E, & Straus, M.A. (Eds.), (1990). Handbook of Family Measurement Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Vincent-Roehling, P.V., & Robin, A.L. (1986). Development and validation of the Family Beliefs Inventory: A Measure of Unrealistic Beliefs Among Parents and Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 693–697. Weiss, R. L. (1980). Strategic Behavioral Marital Therapy: Toward A Model for Assessment and Intervention. In J.P. Vincent (Ed.), Advances in Family Intervention, Assessment, and Theory (Vol. 1, pp. 229–271), Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Weiss, R.L. (1984). Cognitive and Strategic Interventions in Behavioral Marital Therapy. In K. Hahlweg & N.S. Jacobson (Eds.), Marital Interaction: Analysis and Modification. New York: Guilford. Chapter 11 Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C . Kendall Despite its relatively young age, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely researched approaches for treating psychological problems in youth. This chapter provides an overview of CBT from both a procedural and empirical point of view and promotes the increased use of CBT with the problems for which there is demonstrated efficacy. We begin by briefly discussing the cognitive behavioural theoretical framework on which interventions are based, and illustrate the general guiding principles. We then consider CBT’s application with several specific clinical problems in youth. Historical précis and theoretical overview CBT represents an interactional perspective, integrating the cognitive and behavioural schools of therapy into a useful amalgam. The interaction of affect, behaviour, social factors, cognition, and environmental influences is recognised and considered within a comprehensive treatment approach. Learning becomes important not only as it relates to environmental consequences but also as it relates to the information processing occurring within the individual (Kendall, 1985); thus CBT remains consistent with both information-processing and social learning theories (Kendall & Bacon, 1988). At the same time, CBT maintains an empiricist tradition, striving for clinical sensitivity with empirical soundness. Concerning psychopathology and its treatment, the CB approach views psychological problems as stemming primarily from behavioural and cognitive antecedents. Behavioural factors afforded primary consideration by CB theory include a child’s familial and extra-familial environmental experiences (Southam-Gerow, Henin, Chu, Marrs, & Kendall, 1997). These events are examined for evidence of limited learning opportunities or potentially pathgenic experiences (e.g., trauma). In terms of cognitive factors, CB theory emphasises cognitive dysfunction and distinguishes between cognitive distortion and cognitive deficiency (Kendall & MacDonald, 1993). Children either process information in a distorted fashion (e.g., misinterpreting the 276 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall intentionality of others) or their cognitive-processing ability is somehow deficient, leading to action that does not benefit from forethought (Kendall & MacDonald, 1993). These cognitive-processing dysfunctions have been differentially associated with various childhood disorders. Cognitive distortions are thought to underlie anxiety and depression whereas impulsivity and attention problems are linked to cognitive deficiencies. Aggressive and antisocial behaviour have been found to reflect both cognitive distortions and cognitive deficiencies (Kendall & MacDonald, 1993). The therapeutic pathway thus lies in remedying the identified cognitive dysfunction, and providing skills and opportunities to practise these skills, beginning new learning trajectories. Before describing and discussing examples of CB treatment strategies, we first review two additional issues that are considered critical in the formulation of an adequate treatment plan. Knowledge from the field of child development receives particular emphasis in CBT with youth. CB interventions are designed with developmental considerations in mind. For example, the current developmental level of the child (i.e., cognitive ability, current developmental challenges) is assessed to inform the specific intervention. A young, cognitively immature child might benefit less from long, didactic sessions and would be better served by brief, active sessions, often with the cognitive content of the session occurring in vivo. Another developmental consideration involves sensitivity to the context of the developmental challenges facing the child. Therefore, a CB therapist seeing a child dealing with separation anxiety at age nine intervenes within the appropriate developmental challenge (i.e., issues of autonomy). With older children, other themes present themselves as more opportune for the aim of an intervention (e.g., peer-related, achievement-related). CB interventions are active, time-limited, and structured. They are implemented with the therapist as consultant, diagnostician, and educator (Kendall, 1991). The client and therapist engage in a collaborative process in which the client often becomes a “personal scientist” (Mahoney, 1974) once the client and therapist have developed an agreed-upon conceptualisation of the problem. Clients are helped to understand how their inner conversations, thoughts, expectations, and assumptions mediate their behaviour. They are encouraged to perform “in-vivo personal experiments” to test out the results of modifications in their cognitive processes. The resulting behaviour serves as evidence that one’s cognitive structures should not always be held as “truths” and leads to reprocessing and reappraisal of events (FlannerySchroeder, Henin, & Kendall, 1996). In this way, the therapist guides the client in the learning of new skills in behavioural, cognitive, interpersonal, and emotional domains and coaches the client in the use of these new skills (Meichenbaum, 1986). Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 277 Cognitive-behavioural treatment strategies and techniques A main treatment aim of CBT is to help the child construct a coping template (Kendall, 1993, 1994). This is done by developing a new, or modifying an existing cognitive structure for processing information about the world. An important aspect of this process is achieved by having the child learn about his/her own thinking and practise the new ways of thinking in the company of the therapist. This allows the therapist to help the child in altering his/her attributions about past experience and expectations about events in the future. Accomplishing this goal necessitates the utilisation of several treatment strategies and techniques: (a) affective education, (b) relaxation training, (c) social problem-solving, (d) cognitive restructuring/attribution retraining, (e) contingent reinforcement, (f) modelling, and (g) role-plays (Kendall, 1993, 1994; Southam-Gerow et al., 1997). These techniques are tailored for each case, some cases requiring a more comprehensive application than others. The therapist selects among these alternatives in structuring the treatment to fit the presenting problem(s) of the child (Kendall, 1993, 1994; Southam-Gerow et al., 1997). At the beginning of treatment, the problems are identified by both the child and the therapist. This process involves teaching the child to recognise, label, and monitor physiological and emotional cues and then ultimately to control behavioural reactions that accompany these cues (Southam-Gerow et al., 1997). This also involves teaching the child to acknowledge his/her own body reactions. Activities provided in therapy workbooks (e.g., Kendall, 1990; Nelson & Finch, 1996) are aimed at developing the child’s awareness of feelings and situations that produce difficulties for him/her and using the experience as a means to more adaptive coping (Kendall, 1993; SouthamGerow et al., 1997). Once the child is able to identify internal and external situations that produce stress, teaching relaxation skills may be helpful. Cue-controlled and progressive relaxation techniques are used with children. Cue-controlled relaxation involves associating the relaxed state with a cue word generated by the child, such as “calm”. In practice, the child repeatedly vocalises within him/herself the cue word while in the relaxed state. In progressive relaxation, one after the other, major muscle groups are relaxed through systematic tension-release exercises (King, Hamilton, & Ollendick, 1988). This helps the child to recognise bodily tension, allowing him/her to use that arousal as a cue to relax. Relaxation exercises frequently involve relaxation scripts to which the child listens while practising, and may be additionally enhanced by the incorporation of imagery into the scripts. An effective alternative for use in public situations is diaphragmatic breathing exercises, which can also be introduced into the child’s relaxation routine. The process of changing “faulty” thinking to cognitive processes which are 278 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall more functional is sometimes called cognitive restructuring. The first step involves identifying the child’s self-talk, whereby the child is encouraged to express his/her thoughts as “thought bubbles”, similar to those seen in comic strips. Once the content of the child’s self-talk has been identified, the therapist can help him/her replace the non-functional cognition with more adaptive options. Attribution retraining is similar and involves teaching the child to differentiate between internal–external, global–local, and stable–unstable causal attributions. Once a child has identified her/his attributions for a given event, the child and therapist can generate alternative explanations for the circumstances under consideration. Conceptualising therapy as a problem-solving endeavour has many benefits (Kendall & Siqueland, 1989). For example, it helps the child to understand that his/her problems are neither unmanageable nor catastrophic. In addition, a problem-solving approach encourages the child to focus on and evaluate several possible options and solutions to the problem. Problem-solving can be thought of as a sequence (D’Zurilla, 1986; D’Zurilla & Goldfried, 1971), where the child works to describe the problem and the major goals for the solution. Then the child generates alternative solutions and weighs each of these alternatives, considering each in terms of how beneficial it would be in achieving his/her goal. Finally, he/she considers the nature of the outcome, focusing on the attempt at problem-solving, rather than an emphasis on a “perfect” result. Another important technique in CB therapy role playing requires the child and therapist to act out challenging situations. Role playing offers an opportunity for the child to actually practise coping skills and to use solutions already considered for the problematic situations. The therapeutic stance is supportive and the environment is non-threatening. As a result, the child can take his/her first steps towards attempting and ultimately mastering the skills learned in therapy (Kendall, 1993, 1994; Southam-Gerow et al., 1997). After the teaching and practice of problem-solving and/or social skills in the therapy room, it is beneficial for the child to approach and experience in vivo the situations that are stress-producing. Using the tenets from behaviour therapy, this is systematically accomplished by beginning with a less intense stressor and building to situations that are most intense for the child. The exposure can begin imaginally whereby the child, guided by the therapist, imagines him/herself in the situation and then having achieved some mastery, progresses to an actual in-vivo exposure. When a child attempts to face the situations and does so without relying on avoidance behaviours, he/she is rewarded. A cornerstone of behaviour therapy, contingent reinforcement, allows the therapist to shape the child’s behaviour. The child may be helped to behave more adaptively by breaking down the desired outcome into smaller, more manageable steps (i.e., shaping by successive approximations), with the ultimate goal being to teach the child to evaluate his/her own behaviour and provide rewards accordingly (Kendall, Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 279 1993, 1994; Southam-Gerow et al., 1997). Rewards may also be useful in encouraging the child to complete homework assignments outside of the session. These homework assignments are designed to provide further practice with the new coping techniques within a real-life context. In addition, they provide another opportunity for the child to experience mastery. A powerful tenet in CBT is modelling, which is based on the understanding that behaviour can be reduced, acquired, eliminated or enhanced through observation. Several different types of modelling are frequently used by CB therapists: symbolic, live, and participant modelling. Symbolic modelling involves exposure to a video tape of another person facing the same situation with which the child is having trouble. This type of repeated observation of the same sequence enables the child to understand different aspects of the other person’s behaviour on each viewing. As for live modelling, the child observes another person coping directly with a difficult situation. Participant modelling involves the child’s copying of the model, rather than simple observation. The therapist has a unique role in that he/she can act as a coping model throughout sessions by demonstrating coping behaviours as difficulties arise. Rather than provide a model of total and easy success (mastery model) the therapist illustrates the difficulties that may be faced in a situation (coping model). In coping modelling, a full success is not experienced every time but rather, the therapist exemplifies how errors and mistakes can be managed (Kendall, 1993, 1994). A CB therapist, in practice, does not inflexibly follow procedures in manuals or rigidly apply all the delineated strategies and techniques. Rather, therapists carefully select those most suitable and necessary for each child, often restructuring and refocusing as change and progress become more evident. CBT: Applications with particular disorders In the following sections, we consider applications of the CBT approach with four childhood problems: anxiety, depression, aggression, and attentiondeficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). We emphasise the differential application of the more general CB strategies as they are intentionally tailored for each particular type of problem. Additionally, we review empirical studies examining the efficacy of these approaches and describe in some detail the more successful programmes. Internalising versus externalising disorders The difference between internalising (e.g., anxiety, depression) and externalising childhood disorders (e.g., ADHD, aggression) burgeoned out of the research of Achenbach and colleagues (Achenbach, 1985, 1988; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1978; Achenbach & McConaughy, 1987). Internalising disorders are understood to be inner-directed and are characterised by 280 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall overcontrolled behaviour patterns. Externalising disorders, on the other hand, are outer-directed and undercontrolled. The division may also be represented as children with self-focused problems versus children whose problems disturb others or are environment-focused in nature (Achenbach, 1982). Internalising disorders present significant difficulties in their identification and treatment as children suffering from internalising disorders may be easily overlooked because the disorders, anxiety in particular, have symptoms such as inhibition and withdrawal (Flannery-Schroeder et al., 1996). These behavioural tendencies are sharply disparate with the acting-out behaviours of children with externalising disorders. The majority of research studies investigating psychopathology in children and adolescents have focused on externalising behaviour problems (see Kendall & MacDonald, 1993), yet the high frequency of occurrence of internalising disorders (Bernstein & Borchardt, 1991), as well as their significant implications for social (e.g., Rubin, 1985; Strauss, Forehand, Smith, & Frame, 1986), academic (e.g., Benjamin, Costello & Warren, 1990; King & Ollendick, 1989), and future adjustment (e.g., Feehan, McGee, & Williams, 1993; Kovacs, Feinberg, Crouse-Novak, Paulauskas, Pollack, & Finkelstein, 1984a, 1984b), have resulted in a growing shift in research interests toward internalising problems. Anxiety disorders in youth Anxiety disorders appear to be a relatively common form of psychopathology among children and adolescents. Kashani and Orvaschel (1990), studying a sample of 210 youths (age groups were 8, 12, and 17 years), reported anxiety disorders to be the most common disorder diagnosed across the three age groups. In addition, in a New Zealand sample of over 960 children, anxiety disorders were found to exist most frequently, relative to mood disorders, conduct/oppositional disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and substance abuse (Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynsky, 1993). Benjamin et al. (1990) found anxiety disorders to appear four times as often as behavioural disorders by children’s report (9.9% versus 2.6%) but only slightly more often according to parent report (5.6% versus 4.1%). It should be noted that not all anxiety in children is abnormal. A limited number of short-lived fears and worries are a part of normal development (Barrios & Hartmann, 1988). Within a normal range, fear and worry are actually adaptive in development and keep children from harm and potential danger. Children’s fears often take a common trajectory during the course of development, moving from fear of strangers and separation in young children, to fears about personal harm, school, and supernatural events in school-aged children. Concern arises, however, when a child does not move beyond the fears associated with a particular developmental stage or when the worry or fear at a particular stage interferes significantly with the child’s normal functioning (Morris & Kratchowill, 1983). Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 281 Childhood anxiety is a multidimensional construct manifesting physiological, behavioural, and cognitive symptoms. Accordingly, physiological, behavioural, and cognitive models are useful in conceptualising the disorder. Physiologically, the autonomic nervous system produces physical symptoms such as flushed face, perspiration, trembling, and stomach pains (Barrios & Hartmann, 1988). Children with anxiety have also been shown to have increased heart and respiration rates. Behaviourally, anxious children often avoid feared stimuli and situations and display shaky voice, rigid posture, crying, nail-biting, or thumb-sucking. Cognitive theorists hold that anxiety is the product of dysfunctional efforts to make sense of the world (Kendall, 1993, 1994). With anxiety disorders, the nature of cognitive functioning has been characterised as an automatic questioning process (Kendall & Ingram, 1989). This questioning tends to be future oriented, focusing on concerns about possibilities, impending situations, and potential consequences, in conjunction with questions about personal efficacy or one’s ability to deal with these anticipated situations (Kendall & Ingram, 1989). Anxious children focus on social and environmental cues in a distorted manner and appear preoccupied with evaluations by self or others and the likelihood of severe negative consequences (Kendall & Chansky, 1991). Furthermore, anxious children tend to endorse more threat-related self-statements than do non-anxious children when responding to self-statement questionnaires (Ronan, Kendall, & Rowe, 1994) and provide excessive, non-functional coping self-talk on thought-listing tasks (Kendall & Chansky, 1991). Consistent with a multicomponent conceptualisation of anxiety, there is growing acknowledgement that a combination of treatment strategies is most beneficial in treating children with anxiety disorders. In addition, ageappropriate applications of successful strategies can serve as a first step in refining intervention strategies for children (Southam-Gerow et al., 1997). Multicomponent CB intervention programmes for anxiety generally involve children attending 50- to 60-minute weekly sessions, for 16–20 weeks. The first half of the protocol is educational, teaching the child the cognitive skills necessary to alter anxious reactions to anxiety-provoking situations. The therapist’s goal is to help the child build a coping template which can be implemented whenever anxiety-producing situations arise. To accomplish this aim, CB strategies are tailored to target anxious arousal and cognition. Affective education focuses on the recognition of anxious emotions and the accompanying physiological arousal, so that the children can use these symptoms as cues to enact the subsequent phase of their coping plans (Kendall, Kane, Howard, & Siqueland, 1990, for a review, see Kendall et al., 1992). As children continue to practise the skills learned through affective education, they are encouraged to (a) identify and modify the anxious self-talk associated with anticipated negative outcomes, and (b) generate new, more 282 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall adaptive, non-anxious self-talk to challenge their anxious cognition. In addition, problem-solving is encouraged to generate, evaluate, and implement a number of alternative behaviours for use in anxiety-provoking situations. Reinforcement (e.g., tangible rewards or therapist praise) is linked to the child generating realistic appraisals of his/her performance and, eventually, developing the ability for self-praise/self-reinforcement. The second half of treatment focuses on having the children practise their newly learned coping steps in increasingly anxiety-provoking situations. The situations are tailored to each child and are based on his/her own fear hierarchy. Thus, each session gradually focuses on applying the newly learned coping template to another anxiety-producing situation. Throughout treatment, children are encouraged to practise the steps from their coping template outside of the sessions, so as to generalise treatment gains. One strategy developed at Temple University’s Child and Adolescent Anxiety Disorders Clinic (CAADC), where this CB treatment has been developed and evaluated, is to have the child plan and orchestrate a video in which the child gives advice to others about how to cope with anxiety. This casts the child in the role of “expert”, allowing him/her to recognise his/her accomplishments and gain a sense of mastery. It also gives the child the opportunity to organise the material learned during therapy and encourages generalisation of skills. Several studies have investigated the efficacy of CB interventions for children’s phobias and fears (e.g., Hagopian, West, & Ollendick, 1990; Kanfer, Karoly, & Newman, 1975; Singer, Ambuel, Wade, & Jaffe, 1992), medical and dental fears (e.g., Heitkemper, Layne & Sullivan, 1993; Melamed & Siegel, 1975; Peterson & Shigetomi, 1981), and social and evaluative anxiety (e.g., Fox & Houston, 1981; van der Ploeg-Stapert & van der Ploeg, 1986). These studies are important; however, a majority of the studies have not included samples of children diagnosed with anxiety based on structured diagnostic interviews, but instead, have used children with elevated scores on various dependent measures of anxiety. Nevertheless, more recently, several studies have considered the efficacy of CB interventions with children diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. This review will focus on the research examining CB treatments of the following anxiety disorders: (a) separation anxiety disorder (SAD), generalised anxiety disorder (GAD)/ overanxious disorder (OAD), social phobia (SP)/avoidant disorder (AD); (b) obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD); (c) panic disorder; and (d) post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). As for OAD, two studies (Kane & Kendall, 1989; Eisen & Silverman, 1993) evaluated CB therapy using a multiple-baseline design. Both studies followed a multi-trait, multi-measure design with self-, parent-, teacher-, and clinicianreport of children’s functioning. At post-treatment assessment, children demonstrated improvement on self-, parent-, and clinician-reports, with many indices of anxious symptomatology falling to within normative levels Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 283 (Kendall & Grove, 1988). Follow-up results were favourable with most children maintaining treatment gains (only one child continued to experience distress in limited domains). The Eisen and Silverman (1993) study served as a partial replication of the Kane and Kendall (1989) study. However, additional aims were to investigate the relative contributions of cognitive therapy and relaxation training over exposure. Results, though unclear, suggested that cognitive therapy may be more effective than relaxation training. Kendall (1994) conducted and reported the first randomised clinical trial of CB therapy for the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Participants were 47 young people (aged 9–13) diagnosed with one of three childhood anxiety disorders (SAD, AD, OAD) using a structured diagnostic interview and were randomly assigned to either a treatment or a waitlist condition. All waitlisted children were treated at the end of the waitlist period. The CB treatment consisted of four major components: (1) recognising anxious feelings and physical reactions to anxiety; (2) identifying and modifying negative self-statements; (3) generating strategies to cope effectively in anxietyprovoking situations; and (4) rating and rewarding attempts at coping behaviour. The treatment was conducted in two parts: (1) instruction in coping skills and (2) practice in the use of those skills in increasingly anxietyprovoking situations (see treatment manual by Kendall et al., 1990). Dependent measures included a multi-method assessment approach including self-, parent-, and teacher- reports of children’s behaviour, as well as cognitive assessments and behavioural observations. Measures were collected at preand post-treatment, as well as at one-year follow-up. Analyses of the data indicated significant reductions in anxiety for the treated children compared to the waitlist (across nearly all dependent measures). Importantly, 65% of treated children no longer met criteria for their primary anxiety disorder at post-treatment. Examination of clinical significance (Kendall & Grove, 1988) revealed that a significant proportion of children reported levels of anxiety and internalising behaviours falling within the normative range at posttreatment, and follow-up data demonstrated maintenance of treatment gains. Kendall and Southam-Gerow (1996) reported a 3- to 5-year follow-up (average > 3 years) on these participants, which found long-term maintenance of treatment gains. In a second randomised clinical trial, Kendall, Flannery-Schroeder, Panichelli-Mindel, Southam-Gerow, Henin, and Warman (1997) examined the efficacy of the CB treatment procedures with children diagnosed with SAD, OAD, and/or AD. The results were again favourable with over 70% of children no longer having their primary anxiety disorder diagnosis as primary at post-treatment,. Self- and parent-reports, also evidenced improvement, confirming the benefits of the treatment. There have been adaptations of the treatment programme developed by Kendall and colleagues for use with families of children with anxiety disorders. Because of the likelihood of parental involvement in the maintenance of 284 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall children’s behaviours, family-focused treatments have been recommended (e.g., Ginsburg, Silverman, & Kurtines, 1995). In a multiple-baseline study of six anxiety-disordered children and their families, Howard and Kendall (1996) reported that CB procedures produced significant treatment gains which were maintained at 4-month follow-up. Barrett, Dadds, and Rapee (1996) adapted the Kendall (1994) programme and compared individual, family, and waitlist control conditions in a sample of 79 children and their parents. At post-treatment, significantly fewer children in treatment than on waitlist met criteria for diagnosis. In addition, the proportion of children no longer meeting diagnoses in the child plus family treatment (84%) was higher than that in the individual treatment (57.1%). Self-, parent-, and clinicianreport measures indicated greater efficacy of the child plus family treatment, compared to the individual treatment. At a one-year follow-up, gains were maintained for both treatments. The results of the study indicate the added benefits of a family focus in CB interventions with anxious children. Research on CBT with anxious youth serves, not only as an illustration of the efficacy of CB techniques, but also as a template for treatment outcome research with other disorders. Specifically, research on CBT with anxious youth is distinguished by its use of standardised assessment tools, standardised treatment procedures, and the application and evaluation of similar CB treatments by independent research teams. This in turn, has warranted the distinction of “empirically validated treatment” (Kazdin & Weisz, 1998). Obsessive compulsive disorder The efficacy of CB treatment with adult OCD clients has been established (e.g., Foa, Steketee, & Ozarow, 1985; Stanley & Turner, 1995); however, the use of these treatments with children has not been as systematically addressed (for a review, see Henin & Kendall, 1997). Although more than 35 reports of behavioural interventions have been reported in the child OCD literature, the majority have been case reports (e.g., Fisman & Walsh, 1994) or singlecase designs (Hollingsworth, Tanguay, Grossman, & Pabst, 1980; Kearney & Silverman, 1990; for a review, see March, 1995). Randomised clinical trials are needed. An evaluation of a standardised CB treatment for OCD children and adolescents was reported by Piacentini, Gitow, Jaffer, Graae, and Whitaker (1994). The authors assessed the effectiveness of an outpatient treatment that employed therapist-supervised exposure and response prevention. Three children (aged 9, 12, 13) were assessed via structured interviews and child-, parent-, and clinician-reports at pre- and post-treatment, and one year following treatment. Treatment consisted of 10, 2-hour sessions held once per week. In addition to exposure/response prevention, the following treatment strategies were also utilised: (1) coping strategies to manage anxiety during exposure (e.g., cognitive self-statements), (2) a contingency management Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 285 programme (in which children were systematically rewarded for completing in-session tasks), and (3) homework assignments. In addition, the treatment incorporated family sessions designed to educate the family about OCD and help them in developing more adaptive family interactions. Results suggested that two of the three cases showed marked improvement in obsessive compulsive symptoms at post-treatment, as rated on self-report and herapist-report inventories. In addition, gains were maintained at one-year follow-up. In the third case, only minimal improvement was found, although the authors suggest that the patient’s comorbid conditions and high level of associated family psychopathology may have contributed to the difficulties in treatment. A protocol-driven, CB treatment, “How I Ran OCD Off My Land” has recently been developed by March, Mulle, and Herbel (1994) for the treatment of OCD. The 16-week treatment, a compilation of anxiety management training and behavioural exposure/response prevention, comprises four phases: (1) psychoeducation to externalise the OCD (e.g., viewing it as a medical illness, giving it a “nasty nickname”) and a cartographic metaphor to map the child’s experience with OCD; (2) identification of areas where the child has already had some success in resisting OCD, and development of a stimulus hierarchy; (3) anxiety management training (e.g., relaxation training, teaching of adaptive self-talk); and (4) exposure/response prevention in which children practise by selecting items from the stimulus hierarchy. Evaluation of this intervention with 15 children diagnosed with OCD indicated clear treatment gains across multiple self-rated and clinician-rated measures. These gains were maintained at follow-up. Specifically, 10 of the 15 children experienced a greater than 50% reduction in self-report scores at follow-up; six patients were judged asymptomatic at post-treatment, whereas 9 were asymptomatic at follow-up. Despite these promising findings, several aspects of the study limit the conclusions that can be drawn, not the least of which is that the concurrent treatment of 14 of the 15 children with medication prevents clear identification of the active treatment ingredients. Future work with this potentially promising approach requires larger sample sizes and use of comparison and control conditions. Panic disorder There exists a dearth of studies examing panic disorder in children and adolescents. Until recently, there were questions as to whether or not panic disorder occurred in childhood or adolescence. Although reported prevalence rates of the disorder have ranged from 0.6% (Whitaker et al., 1990) to 12% (Hayward, Killen, & Taylor, 1989), these findings should be considered preliminary due to methodological differences (see Moreau & Weissman, 1992). Nevertheless, retrospective reports of adults with panic disorder suggest that the panic attacks began in childhood (e.g., Sheehan, Sheehan, & 286 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall Minichiello, 1981; Thyer, Parris, Curtis, Nesse, & Cameron, 1985). In addition, case studies have been reported in which the authors describe cases of panic disorder in children (e.g., Black & Robbins, 1990; Biederman, 1987; Moreau, Weissman, & Warner, 1989); however, these reports are few in number and several have failed to use structured diagnostic interviews. CB therapies with adult panic sufferers hold promise (e.g., Craske, 1988) and have been recommended in the treatment of panic disordered children. However, few empirical or controlled studies have been conducted with children or adolescents. To date, the only systematic study involved a multiple-baseline design with four adolescents diagnosed with panic disorder with agoraphobia (Ollendick, 1995). Treatment included relaxation exercises, cognitive coping skills training, and exposure. Results demonstrated enhancement of selfefficacy and reductions in panic attack frequency and agoraphobic avoidance. Self-report measures post-treatment also indicated lowered levels of anxiety and depression. Generally, treatment gains were maintained at 6-month followup. These findings are positive but preliminary, and research is needed to substantiate the validity of panic disorder diagnoses in children and to further investigate efficacious treatment programmes. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) PTSD symptomatology has been observed in children and adolescents following traumatic events including death, fires, natural disasters, and physical or sexual abuse, and treatment approaches have been varied. There are approaches rooted in the behavioural, cognitive behavioural, psychodynamic, family, and group traditions; yet the utility, or relative utility, of these procedures with children remains largely unexplored (Lyons, 1988) with one exception (Deblinger, McLeer, & Henry, 1990). Nevertheless, results of studies of adults with PTSD have been promising and point toward the efficacy of CB procedures (Fairbank & Keane, 1982; Frank & Stewart, 1983; Kilpatrick, Veronen, & Resick, 1982). The only study to date investigating CB strategies with children examined the treatment of sexually abused children suffering from PTSD (Deblinger et al., 1990). Participants were 19 girls (aged 3–16) and their non-offending parent(s). Parents and children participated in structured diagnostic interviews and completed various self-report measures of the children’s adaptive functioning. The 12-session intervention included techniques such as gradual exposure, modelling, coping, and prevention skills training. Findings demonstrated significant improvements in PTSD symptomatology. Furthermore, at post-treatment all subjects failed to meet PTSD diagnostic criteria. These results are favourable and suggest that CB therapy may be quite promising for sexually abused PTSD children. However, strong conclusions are not yet possible. Future research should include larger sample sizes, follow-up assessments, samples of children with PTSD arising from traumas other than Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 287 sexual abuse, and comparisons of CB and other forms of treatment (for a review, see Lyons, 1988). Summary Across the disorders reviewed thus far, CB treatment of anxiety disorders appears to be an effective approach in the alleviation of such disorders. CB treatments hold promise with SAD, OAD, AD, and OCD, although the apparent differential efficacy may be due to the disproportionate amount of research using samples with these disorders compared with other anxiety disorders such as panic and PTSD. Treatment development and evaluation is still needed for panic disorder and PTSD in youth. Unipolar depression in children and adolescents The recent interest in affective disorders in youth has been prompted in part by the finding of significantly higher rates of these disorders in children than previously believed, and in part because adolescent depression appears to predict subsequent adult maladjustment. A number of rigorous epidemiological studies of affective disorders have yielded prevalence rates for children around the 2% mark (Anderson, Williams, McGee, & Silva, 1987; Costello et al., 1988). Among clinic-referred children, rates of depression are significantly higher – approximately 13–15% meet diagnostic criteria for depression (Kashani, Cantwell, Shekim, & Reid, 1982; Kazdin, French, Unis, & EsveldtDawson, 1983). Among adolescents, depressed mood is a very common occurrence with approximately 40–80% of adolescents reporting feelings of misery and depression (Kashani et al., 1987; Rutter, Tizard, & Whitmore, 1970; Gotlib, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1995). The prevalence of clinical mood disorders in adolescents is also more elevated than in children, with rates of major depressive disorder (MDD) and dysthymia approaching 3–5% (Kashani et al., 1987). Importantly, although there appear to be no gender differences in the rates of mood disorders among younger children, rates of depression increase dramatically among girls as they approach early adolescence. Among adolescents, the prevalence of MDD in girls is nearly twice as high as that of adolescent boys (e.g., 3.8% for girls versus 2.0% for boys; Lewinsohn et al., 1993). Although early onset MDD may represent a more serious form of affective illness (Kovacs, 1996), the presentation of MDD in children is very similar to that of adults. Children with depression experience significant impairments in psychosocial functioning (e.g., Gotlib & Hammen, 1992; Lewinsohn, Clarke, & Rohde, 1994) including lower peer status and impaired social functioning (Cole, 1991; Hops, Lewinsohn, Andrews, & Roberts, 1990; Larson, Raffaelli, Richards, Ham, & Jewell, 1990; Shah & Morgan, 1996; Wierzbicki & McCabe, 1988) and may be more vulnerable to the effects of subsequent 288 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall stressful life events (Asarnow, Carlson, & Guthrie, 1987), and suicidality (Andrews & Lewinsohn, 1992). Depression in youth is associated with a high rate of comorbid conditions, most notably, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, and conduct disorders (Brady & Kendall, 1992; Lewinsohn et al., 1993; Strauss, Last, Hersen, & Kazdin, 1988). Furthermore, the families of these children are marked by lower family cohesion (Garrison, Jackson, Marsteller, McKeown, & Addy, 1990) and negative parent–child interactions (Cook, Asarnow, Goldstein, Marshall, & Weber, 1990; Dadds & Barrett, 1996). Supporting the downward extension of adult models of depression (e.g., Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978; Beck, 1967, 1976), the cognitive processing of depressed children is characterised by distortions in attributions, self-evaluations, and information-processing. Depressed children tend to attribute failure to internal, stable, and global causes and successes to external, transient, and specific causes. They distort experience in a manner consistent with a negative view of the world (Curry & Craighead, 1990; Kaslow, Stark, Prinz, Livingston, & Tsai, 1992; Joiner & Wagner, 1995) and display information-processing errors such as catastrophising the consequences of negative events, and selectively attending to the negative features of events (Kendall & MacDonald, 1993; Leitenberg, Yost, & Carroll-Wilson, 1986). The self-perceptions and self-evaluations of depressed children reflect these information-processing distortions. For example, depressed youth set more stringent standards for their performance, evaluate themselves more negatively, and tend to self-reinforce less than their non-depressed peers (Kaslow, Rehm, & Siegel, 1984; Kendall, Stark, & Adam, 1990; FlannerySchroeder et al., 1996). Most CB treatment interventions contain multiple components designed to address the diverse range of possible contributing factors to the depression. CB models for the treatment of childhood depression adapt strategies from adult CB treatments (Hops & Lewinsohn, 1995; Stark & Kendall, 1996) and integrate cognitive restructuring techniques, social skills training, self-control skills, and traditional behavioural techniques into a comprehensive treatment package. Although these various components are taught in a logical, additive sequence, flexibility in the treatment programme is maintained so that the components of the treatment programme reflect the particular concerns of the child or adolescent. The central goal of therapy is to help the child recognise his/her depressotypic beliefs and causal attributions (Lewinsohn et al., 1996; Stark & Kendall, 1996) to help him/her adopt an active role in influencing his/her moods. Cognitive procedures (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) such as cognitive restructuring are employed to modify the child’s thinking and to foster more adaptive information-processing. The therapist and child work together to recognise maladaptive cognitions and irrational beliefs, which are then challenged and evaluated (Beck et al., 1979). The therapist monitors the Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 289 child’s speech throughout the session for evidence of depressogenic thinking and explores the context in which the thought occurs. The therapist and child then collaborate in exploring alternative, more realistic interpretations (Stark, Brookman, & Frazier, 1990). To enhance this skill, the child is given examples of other depressogenic cognitions for which he or she must practise developing constructive coping responses (Stark et al., 1990). Similarly, the relationship between the child’s tendency to make unrealistic causal attributions and his/her depressed mood is examined with reattribution training. Maladaptive causal attributions for events are challenged in an effort to demonstrate that the interpretation of events is within the child’s control. Given the difficulties experienced by depressed children with self-reinforcement, training in self-control skills (i.e., self-monitoring, self-evaluation and self-reinforcement) is emphasised. Children are taught to self-monitor or observe their own behaviour to serve both as a means of assessment and as a means of developing accurate, more positive self-appraisals. In self-evaluation training, children are instructed to set realistic expectations for their performance, to critically examine their depressotypic beliefs, to evaluate themselves less negatively, and to develop the necessary skills to improve their performance. Finally, self-reinforcement is emphasised to help children learn to reward themselves for accomplishing relevant tasks, and to punish themselves less frequently (Hops & Lewinsohn, 1995; Stark et al., 1990). In addition to these cognitive techniques, a number of behavioural procedures are incorporated into the treatment including (a) activity planning to increase the frequency of pleasurable activities, (b) assertiveness training and conflict resolution, (c) social skills training (conversation skills, planning social activities, strategies in initiating and maintaining friendships, and dealing with conflict), (d) future planning (teaching the child to use his or her newly acquired skills to anticipate and prepare to cope with future problems and prevent relapse), and (e) anxiety reduction techniques such as relaxation and imagery training (Hops & Lewinsohn, 1995; Nezu, Nezu, & Perri, 1989; Stark et al., 1990. Several outcome studies have documented the efficacy of CB treatment for depressed youth (e.g., Reynolds & Coats, 1986; Stark, Brookman, & Frazier, 1990; Stark, Reynolds & Kaslow, 1987). Lewinsohn and his colleagues (i.e., Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops, & Andrews, 1990; Lewinsohn, Clarke, & Rhode, 1994; see Lewinsohn et al., 1996 for a review) have developed a manualised CB treatment for depressed adolescents: the Adolescent Coping With Depression course. In one clinical trial, 59 adolescents diagnosed with MDD or intermittent depression (DSM-III) were assigned to either group treatment (GRP), group treatment with a concurrent parent group treatment (GRP + parent), or waitlist. Treatment consisted of a 16-week protocol including social skills training, negotiation, and problem-solving compoents. Results indicated that adolescents in both treatment conditions evinced 290 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall significant changes across dependent measures (e.g., Beck Depression Inventory) from pre- to post-treatment (no significant differences were found between the treatment conditions). Importantly, 46% of treated participants (versus 5% of waitlist controls) no longer met criteria for an affective disorder at post-treatment (Lewinsohn et al., 1990). A second clinical trial replicated the findings of the first: the two treatments did not differ significantly but both resulted in significant changes in self-reported levels of depression and percentages of children no longer meeting diagnostic criteria. In this study, 65% of the adolescents in the GRP condition and 69% in the GRP + parent condition (versus 48% of the waitlist) no longer met DSM criteria for depression at post-treatment (Lewinsohn et al., 1994). When compared with other treatment approaches, CB treatment appears to be more successful in treating adolescent depression. In a study directly comparing CBT to a traditional counselling programme, the CB treatment led to greater improvements in depression and reductions in depressive thinking (Stark, Rouse, & Livingston, 1991). CBT has also demonstrated superiority in reducing adolescent depression, as compared to a relaxation training programme (Wood, Harrington, & Moore, 1996). Kahn, Kehle, Jenson, and Clark (1990) compared the efficacy of various psychological interventions (i.e., CBT, relaxation training, self-modelling) to a waitlist control group and reported that although all three treatment groups evidenced significant gains on a number of paper-and-pencil assessments at posttreatment, the CB therapy and relaxation training modalities exhibited the greatest benefits. Additional studies assessing the relative efficacy of CB therapy, systemic-behavioural, and non-directive supportive treatments for suicidally depressed youth are currently under way (Brent et al., 1996). Given the success of CB interventions in the treatment of depressed youth and the increased risk for depression among youth with elevated depressive symptomatology, work has been directed toward developing preventative interventions. Clarke et al. (1995) developed the “Coping with Stress Course” consisting of group sessions in which at-risk adolescents are taught cognitive techniques to identify and challenge negative, irrational thinking. One hundred and seventy-two adolescents identified as at-risk for future depressive episodes were assigned to either the prevention intervention or a usual-care control condition (participants were free to continue with any pre-existing interventions). Results indicated that adolescents receiving the cognitive group intervention were less likely to develop clinical depression, displaying an incidence of depressive disorder of 14.5% over a 12-month period versus 25.7% for the control condition. These findings support the use of CB interventions in the prevention of depression but, as the authors note, the rates of affective disorder in the treatment condition were still greatly elevated (approximately twice the rate in the general population). As suggested by a recent study of a manualised, psychoeducational programme, prevention Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 291 efforts which link cognitive strategies to family life experiences, for example by targeting family communication and parental understanding of depression, may also serve to increase behavioural and attitudinal change and help produce long-term changes in depressive symptomatology (Beardslee et al., 1996). The long-term effects of CB therapy for depressed children have received somewhat mixed support. Although several studies have shown maintenance of treatment gains over short-term follow-up periods of 4 to 8 weeks (e.g., Kahn et al., 1990; Reynolds & Coats, 1986; Stark et al., 1987), longer-term assessments have yielded inconsistent results. For example, Stark et al. (1991) noted that some treatment gains were not maintained at 7-month follow-up. Conversely, Lewinsohn et al. (1994) reported an increase in the rate of recovery over a 2-year follow-up period for depressed adolescents who received CB treatment. For example, 81.3% of adolescents receiving CB treatment had recovered at 12-months post-treatment, and 97.5% had recovered at 24 months. Although recent studies have suggested that CBT may also be successfully applied to relapse-prevention (Gillham, Reivich, Jaycox, & Seligman, 1995; Kroll, Harrington, Jayson, Eraser et al., 1996), these inconsistent results point to the need for a greater understanding of the individual and contextual factors that may place depressed youth at risk for relapse (Sanford, Szatmari, Spinner, Munroe-Blum et al., 1995). Aggressive behaviour in youth Although most children occasionally display aggressive behaviour, concern about the aggression arises when it is severe and frequent or occurs across multiple settings. Aggression in children is predictive of subsequent aggression and maladjustment (Wilson & Marcotte, 1996), with these children evincing increased levels of peer rejection (Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982), drug use and difficulties in school. The impact of aggression on family life is highlighted by the finding that one-third to one-half of all child treatment referrals by parents or teachers are for aggressive behaviours (Patterson, Reid, Jones et al., 1975). With regard to the long-term effects, aggression tends to remain stable over time (Dumas, Neese, Prinz, & Blechman, 1996; Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1996; Olweus, 1984) and has been associated with adult antisocial behaviours, marital discord, and subsequent familial transmission (Eron, Huesmann, Dubow, Romanoff, & Yarmel, 1987; Huesmann & Eron, 1984; Huesmann, Lefkowitz, Eron, & Walder, 1984; Olweus, 1979). Although there is evidence to suggest that biological forces may impact the expression of aggression in children (Bates, Bayles, Bennett et al., 1991; Brennan, Mednick, & Kandel, 1991; Pincus, 1987; Raine, Brennan, & Mednick, 1994; Tremblay, Pihl, Vitaro et al., 1994), the cognitive behavioural approach has proven useful in both conceptualisation and treatment of 292 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall childhood aggression and conduct disorder. As in other disorders, it is the child’s appraisal and expectations of the environment that are believed to mediate the connection between environmental events and anger arousal (Kendall, Ronan, & Epps, 1991). In particular, Dodge’s (1980, 1986) fivestage model of social information processing has received support in explaining the distortions and deficiencies that characterise the cognitive processing of aggressive children. The first two steps in Dodge’s model consist of social-cognitive appraisals in which social cues are encoded, processed and interpreted (Kendall & MacDonald, 1993; Lochman, White, & Wayland, 1991). The next three stages in the model constitute social problem-solving and require the generation of potential alternative responses, the evaluation of probable consequences and selection of the most desirable response, and the enactment of the chosen response and social behaviour. Aggressive children are believed to experience difficulties at each of these five stages, resulting in deviant or hostile social behaviours. For example, studies have demonstrated that aggressive boys attend to fewer relevant social cues than do non-aggressive boys and demonstrate a bias towards the selective recall of hostile cues (Dodge & Newman, 1981; Milich & Dodge, 1984). Moreover, the social processing of these children is characterised by a “hostile attributional bias” (Milich & Dodge, 1984, p. 472), in which they overestimate the amount of hostile intent by others in ambiguous interpersonal situations (Milich & Dodge, 1984; Dodge, 1980; Dodge & Newman, 1981). With regard to their problem-solving skills, aggressive boys have consistently been shown to generate less mature or verbally assertive, and more aggressive responses (Deluty, 1981; Lochman & Lampron, 1986; Milich & Dodge, 1984; Rabiner, Lenhart, & Lochman, 1990; Richard & Dodge, 1982). Aggressive boys place greater value on achieving control over other children, value aggression as a legitimate means to obtain tangible rewards or social dominance, express greater confidence in their ability to aggress, view aggression as increasing self-esteem, and minimise the negative outcomes of aggression (e.g., victim’s suffering; Boldizar, Perry, & Perry, 1989; Erdley & Asher, 1996; Huesmann & Guerra, 1997; Perry, Perry, & Rasmussen, 1986; Slaby & Guerra, 1988). A distinction has been made between reactively and proactively aggressive children, with boys identified as proactively aggressive displaying lower adjustment and greater criminality in adulthood (Pulkkinen, 1996). Reactively aggressive boys have also been shown to display inadequate encoding and problem-solving processing patterns, whereas proactively aggressive youths tend to demonstrate anticipation of positive outcomes for aggression and fewer relationship-enhancing goals during social interaction (Crick & Dodge, 1996; Dodge, Lochman, Hamish, Bates et al., 1997). Given these difficulties, CB approaches in the treatment of childhood aggression have focused primarily on teaching social problem-solving skills to be used in situations where interpersonal conflicts arise. Social skills training is particularly amenable to group as well as individual treatment. Children are Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 293 taught a series of problem-solving steps to identify environmental social cues, practise perspective-taking, analyse options in solving interpersonal problems, and consider the consequences of the chosen solutions. Kendall and his colleagues (Kendall, 1992; Kendall & Braswell, 1982, 1985, 1993) have described a programme for impulsive children that presents social problemsolving steps as self-instructions to “Stop and Think”. Children are encouraged to: (a) define the problem, “What can I do?”; (b) approach the problem, “I have to look at all the possibilities”; (c) focus their attention, “I’d better concentrate and focus and think only of what I’m doing now”; (d) select an answer, “I think it’s this one”; and (e) reinforce themselves, “I did a good job”. Coping self-statements are also employed when children experience difficulty applying the steps or arrive at undesirable solutions (for example, “Next time I’ll try to go slower and maybe I’ll find a more positive solution”). To promote the generalisation of skills outside of the sessions, the “Stop and Think” steps are individualised for each child, in that the child works together with the therapist to develop personally meaningful coping self-statements. Recently, Kazdin and his colleagues (Kazdin, Bass, Siegel, & Thomas, 1989; Kazdin, Esveldt-Dawson, French, & Unis, 1987) have integrated Kendall and Braswell’s (1982, 1985) approach with earlier work by Spivack and Shure (1974) into a more comprehensive treatment package for aggressive children. Behavioural contingencies are a particularly important feature of the CBT programme given the frequent aversiveness of aggressive children’s behaviours. Thus, in addition to self-evaluation and self-reward both inside and outside the session, emphasis is placed on social rewards such as praise or encouragement from the therapist. A response-cost contingency may be implemented whereby “points” are earned by the child for accomplishing various in-session tasks, or are lost for failing to perform these tasks (e.g., answering task questions incorrectly, going too fast). The points can then be exchanged for a small prize or reward at the end of the session. Time-out and seclusion contingencies may also be incorporated into the treatment to manage uncontrollable behaviours (Kazdin et al., 1987). In addition to social problem-solving skills training and behavioural contingency training, affective education has been incorporated into several CBT treatment packages. For example, Lochman and colleagues have developed the Anger Coping Program (Lochman, Lampron, Gemmer, Harris, & Wyckoff, 1989) and Nelson and Finch (1996) have designed the “Keeping Your Cool” workbook, to teach children to identify physiological and affective cues and environmental precipitants of anger arousal. Children are aided in the recognition and labelling of their emotional experiences and are instructed in self-monitoring/self-control strategies such as self-talk. Videotapes of children applying the coping strategies are employed to provide a model of awareness of physiological reactivity and to exemplify problemsolving strategies. Feindler (1991) has elaborated a similar programme, 294 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall including arousal management, cognitive restructuring, and problem-solving and prosocial skills training components. Relaxation training and visual imagery may be introduced as an additional means of controlling physiological arousal, and the application of these various strategies in difficult interpersonal situations is emphasised and rehearsed in session (Baum, Dark, McCarthy, Sandier, & Carpenter, 1986; Feindler, Ecton, Kingsley, & Dubey, 1986; Garrison & Stolberg, 1983). The application of standardised CB treatments to aggressive youth has been supported by the findings of several programmatic research efforts. Lochman and colleagues have demonstrated the efficacy of their “Anger Coping Program” with aggressive children (Lochman, 1992; Lochman, Burch, Curry, & Lampron, 1984; Lochman & Lenhart, 1993; Lochman, Nelson, & Sims, 1981). Similar treatment effects have been reported for clinical samples of aggressive children. For example, Kazdin and his colleagues examined the effectiveness of problem-solving skills training with psychiatric inpatient children referred for antisocial behaviours (Kazdin et al., 1987, 1989). Results indicated that children receiving the problem-solving skills training treatment displayed greater decreases in externalising and aggressive behaviours, and increases in prosocial behavioural and overall adjustment, than did children in the control condition or children receiving non-directive relationship therapy (Kazdin et al., 1987a). The efficacy of social cognitive interventions in reducing aggression and increasing socially appropriate behaviours has also been demonstrated with behaviourally disordered adolescents (Etscheidt, 1991), conduct-disordered youths attending a day treatment programme (Kendall, Reber, McLeer, Epps, & Ronan, 1990), incarcerated juvenile delinquents (Hawkins, Jenson, Catalano, & Wells, 1991), and male adolescents hospitalised at psychiatric facilities for behaviourally disordered youth (Feindler et al., 1986; Maag, Parks, & Rutherford, 1988). Although CBT’s emphasis on cognitive and social problems appears to be a promising approach, the evidence for its effectiveness with aggressive young people has not been entirely supportive. In particular, the short-term success of CBT in the treatment of aggressive children has been tempered by difficulties with generalisation of treatment effects and persistently elevated levels of disruptive behaviours in normative comparisons. For example, long-term follow-up assessments suggest that decreases in aggressive or delinquent behaviours are often not maintained over time (Kazdin, 1987a; Kendall & Braswell, 1985; Lochman, 1992) or are not generalised across situations (e.g., classroom behaviours; Baum et al., 1986; Lochman, Burch, Curry, & Lampron, 1984). Moreover, although treated children may display improvements in the social-cognitive processes believed to mediate aggressive behaviours, these do not always translate into decreases in observable aggression (Camp, Blom, Herbert, et al., 1977; Coats, 1979). Similarly, treated children may demonstrate positive changes on some measures of aggression (e.g., disciplining for fighting) or improvements in interpersonal skills, while Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 295 evidencing little or no change on other measures of aggressive behaviour such as teacher ratings (Baum et al., 1986; Garrison & Stolberg, 1983; Kettlewell & Kausch, 1983; Lochman et al., 1991). These potential limitations with child-focused CB treatment have prompted investigators to examine the child and therapy variables that may impact treatment efficacy. For example, Lochman and his colleagues have found that longer treatment (i.e., 18 weeks versus 12 weeks) and higher initial levels of disruptive or aggressive behaviours may be associated with greater decreases in aggression at post-treatment (Lochman, 1985; Lochman, Lampron, Burch, & Curry, 1985). Although these studies represent a first step, they point to the need for a greater understanding of the various client characteristics that can impact treatment and underscore the need for a flexible treatment approach. It may also be that short-term, child-focused interventions are not the optimal solution for aggressive young people, and that CBT may need to add a focus on the familial variables implicated in the development and maintenance of antisocial behaviour in children (Patterson, 1982). Additionally, there has been a failure to consider the larger societal context in the expression of disorder (Staub, 1996). Adopting a broader-based treatment strategy in which social-cognitive training interventions are integrated within a family or societal framework may result in greater generalisation or maintenance of treatment effects (Estrada & Pinsoff, 1995; Kazdin, 1987b). Although CBT has consistently demonstrated greater treatment effects than parent-focused treatments alone, recent studies have suggested that a combined treatment approach may be particularly effective (Frankel, Myatt, & Cantwell, 1995; Kazdin et al., 1987). Children receiving CBT in combination with parenttraining tend to display greater improvements in family interactions than those receiving CBT alone, and maintenance of these improvements at follow-up (Webster-Stratton, & Hammond, 1997). Parents participating in family-based interventions may also directly benefit from treatment by themselves experiencing attitudinal changes and by improving their child management skills (Estrada & Pinsof, 1995). Given that children with aggressive behaviours often evince a range of behaviour problems, as well as concomitant academic and emotional difficulties or family dysfunction, a multifaceted treatment approach combining child-focused CBT with academic tutoring, parent management training and/or family therapy, and medication may be recommended (SouthamGerow et al., 1997). Ideally, treatment could intervene in multiple settings, including the home, school, peer group, and community (Miller & Prinz, 1990). In addition, interventions aimed at parents’ own problems may represent another useful component to the treatment of antisocial young people. At this time, few studies have systematically evaluated an integrative treatment approach, although some investigators have reported promising findings (Frankel et al., 1995; Henggeler, Melton, & Smith, 1992; Horn & Sayger, 1990; Kazdin, Siegel, & Bass, 1992; Webster-Stratton, 1994). 296 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall In addition to a multisystemic treatment approach, some researchers, noting the stability of aggression across the lifespan, have advocated a “chronic disease” model for the antisocial or aggressive child (Kazdin, 1987b, 1993; Miller, London, & Prinz, 1991; Tolan, Guerra, & Kendall, 1995; Wolf, Braukmann, & Ramp, 1987). Such a model may increase treatment efficacy by emphasising preventative efforts for at-risk young people, and may provide the most cost-effective way for society to deal with the potentially chronic nature of antisocial behaviour. Such programmes, which often emphasise interpersonal relationships, limit-setting and problem-solving, have been implemented with inner-city children and adolescents with behavioural or academic problems (Spivack & Shure, 1974). Results have been positive though preliminary. Further research is required to clarify the long-term impact of such a community-based approach. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) ADHD represents one of the most common reasons for a child’s referral to a clinic or school psychologist, affecting approximately 3 to 5% of children (Szatmaris, Offord, & Boyle, 1989). In addition to the three core symptom clusters of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Anastopoulos & Barkley, 1992), children with ADHD often evince a number of associated difficulties, including (a) academic underachievement; (b) cognitive and language performance deficits; (c) inconsistent task performance; (d) limited performance in rule-governed situations; (e) impaired social functioning in peer and family settings; (f) comorbid behaviour problems like conduct disorder (CD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD); and (g) comorbid internalising disorders like generalised anxietydisorder (GAD) and depression (Anastopoulos & Barkley, 1992; August, Realmuto, MacDonald, Nugent et al., 1996; Barkley, 1990; Biederman, Faraone, Milberger, & Guite, 1996b; Erhardt & Hinshaw, 1994; Frederick & Olmi, 1994; Hinshaw, 1987, 1992; Kendall, 1994; Landau & Moore, 1991; Pennington, Groisser, & Welsh, 1993; Wilson & Marcotte, 1996). Although the disorder must be present before age 7 to be diagnosed, ADHD typically follows a chronic course, often persisting into adolescence. Historically ignored, diagnoses of ADHD in adulthood are increasing (Barkley, 1990; Biederman, Faraone, Milberger, Curtis et al., 1996a; Wender, 1987). CBT initially appeared to be a theoretically-consistent treatment option to address the numerous cognitive and behavioural difficulties associated with ADHD. Several CB packages such as the “Stop and Think” treatment programme designed by Kendall and Braswell (1982, 1985) were applied to address these children’s difficulties in rule-governed situations, impulsivity, and socially-related problems. As noted above, these interventions typically emphasise rewards and response-cost contingencies, modelling of problemsolving strategies, affective education, homework tasks, self-evaluation Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 297 training, perspective-taking activities, and ample in-session and extra-session practice of these skills (Kendall & Reber, 1987). The overarching goal lies in assisting children in the application of problem-solving to reduce impulsive behavioural responses and promote consideration of alternative, more adjustment-enhancing responses. The restless nature of children with ADHD requires less didactic, more action-oriented sessions, in which skills are modelled and practised “on-the-run”. (Meichenbaum & Goodman, 1971; Southam-Gerow et al., 1997). Despite initial enthusiasm, outcomes of the CBT approach have been somewhat disappointing. Although CBT appears to be most effective in addressing certain features of ADHD such as impulsivity, changes in the other important symptoms of ADHD have been modest, at best. In addition, early studies documenting success of CB interventions typically treated nonclinical samples of impulsive children, limiting their generalisability to an ADHD population (Kendall & Braswell, 1985; for review, see Baer & Nietzel, 1991). Other studies using clinical samples have documented limited success (Abikoff, 1991; Abikoff & Klein, 1987; for a review, see Miller, 1994). A reason for the limited success of CBT may lie in the heterogeneity of the problems displayed by children who receive the diagnosis of ADHD. ADHD has a high rate of comorbidity with a wide range of both internalising and externalising disorders (e.g., ADHD and CD occur in tandem from 30% to 50% of the time in clinical samples; Biederman, Newcorn, & Sprich, 1991; Hinshaw, 1992), as well as learning difficulties and substance abuse, leading several researchers to question the existence of an “independent” ADHD (Abikoff, 1991; Hinshaw, 1987). As with aggression in youth, comorbidity figures imply that interventions with a highly restricted focus may not be best suited to address the multiplicity of problems accompanying the diagnosis of ADHD. CBT has demonstrated efficacy for impulsivity in children and perhaps may be indicated when impulsivity plays a primary role in a child’s dysfunction. Additional approaches may need to be integrated within the treatment protocol to address supplementary issues. CBT has demonstrated success with other childhood disorders such as anxiety (Kendall, 1994; Kendall et al., 1997); thus it may be advantageous to include these treatment strategies when working with a child with both ADHD and anxiety. Failure of any treatment approach to recognise the diversity of ADHD youth will likely result in limited success. Poorer outcomes may also be, in part, attributable to the failure of CBT to address issues of inattention in the treatment of young people with ADHD. The attentional deficits present in most children with ADHD mean that their ability to learn, apply, and generalise problem-solving skills may be greatly limited. Early treatment gains may fail to generalise outside the therapy room where strict contingencies are not in place. In fact, no extant treatment can claim comprehensive change in the multiple domains of problems evidenced in many ADHD children (Southam-Gerow et al., 1997). 298 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall The limited success of CBT alone, and the demonstrated success of medications like methylphenidate and imipramine (for a review see Spencer, Biederman, Wilens, Harding, et al., 1996), has led to the combining of CBT with medications in the treatment of ADHD (Whalen & Henker, 1991). Medication can manage the symptomatic behaviour of ADHD children and conceivably, the implementation of CBT along with medication could lead to increased treatment efficacy. The increased attentional ability and task persistence of children receiving medication may increase their ability to acquire the skills taught in CB interventions. Moreover, integrating these two treatment approaches may enable lower doses of medication to be as effective as higher doses of medication alone, possibly reducing the likelihood of undesirable medication effects (e.g., increases in tic behaviour or sleep disturbances; Horn, Ialongo, Pascoe et al., 1991). Finally, the combination of CB and medication may lead to improvements in areas that have not been demonstrated when the therapies are used separately. For example, although medication may be successful in increasing attentional capacity, gains in academic domains and social problem-solving have not been demonstrated. Ostensibly, CBT addresses these areas (Southam-Gerow et al., 1997). Unfortunately, results of some combined interventions have not been as strong as hoped. Although a two-case study analysis provided evidence for the possibility that combined interventions may allow lower doses of medication (Abramowitz, Eckstrand, O’Leary et al., 1992), other studies have failed to find increased efficacy of a combined intervention (Brown, Wynnen, & Medenis, 1985; Hinshaw, Henker, & Whalen, 1984; Nathan, 1992). In a largescale randomised clinical trial (n = 96), Horn and colleagues (1991) investigated the effects of a combined intervention including methylphenidate, child-focused CBT (based on Camp & Bash, 1981; Kendall & Braswell, 1982; Meichenbaum, 1977), and a behavioural parent-training programme (Barkley, 1981; Forehand & McMahon, 1981; Patterson, 1976). Similar to Abramowitz et al.’s (1992) findings, lower doses of methylphenidate in combination with the psychosocial interventions led to gains equivalent to those achieved by higher doses of medication alone. However, no evidence was found for the superiority of the combined treatment relative to medication alone. Overall, the extant results led Anastopoulos and Barkley (1992) to conclude that “despite the intuitive appeal of [combined interventions] . . . there presently exists little empirical justification for utilising such combinations”. (p. 425). These findings suggest that simple linear models of ADHD must be replaced by models that do not rely on single causal explanations. Such multimodal approaches are found in the combination of parent-training approaches with medication and child-focused CBT (Horn et al., 1987; Sheridan, Dee, Morgan, McCormick et al., 1996), and the use of group(Braswell, 1993) and school-based (Bloomquist, August, & Ostrander, 1991) interventions. Parent- and school-based interventions in particular have Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 299 theoretical importance. Given the ADHD child’s self-regulation difficulties, consistent, firm, and loving environmental regulation may enhance a child’s ability to self-regulate. This possibility may be further enhanced by the use of medication. Additionally, future designs could also consider the peer-related difficulties demonstrated by ADHD children. Although these children appear to “know” appropriate social skills, they tend not to exercise those skills (Landau & Moore, 1991). Given the importance of peer relations in development and adjustment, and the demonstrated peer-relations disturbances of ADHD children, remedies along this line are sorely needed (Erhardt & Hinshaw, 1994; Parker & Asher, 1987). Moving forward The internal workings of CBT with youth have been developed and advanced – they are developmentally sensitive, include age-appropriate materials (e.g., workbooks) and have empirical support documenting that the treatment can be efficacious in reducing symptomatology. The efficacy is not universal, however, as some disorders are more and others less responsive to the treatment. In contrast, the external or contextual forces that influence treatment outcomes require additional attention. Clinical implementation and research evaluation are needed to assess (a) the merits of increased family/parent involvement; (b) the factors that moderate the benefits of family/parent involvement; (c) the role of peers and the school settings; and (d) the use of groups and systems interventions. In one sense, CBT is ready to move forward on the road from treatment development and evaluation to community applications with evaluations of effectiveness. References Abikoff, H. (1991). Cognitive training in ADHD children: Less to it than meets the eye. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 24, 205–209. Abikoff, H., & Klein, R.G. (1987). Reply: Cognitive training in treatment of hyperactivity in children. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 296–297. Abramowitz, A.J., Eckstrand, D., O’Leary, S.G., & Dulcan, M.K. (1992). ADHD children’s responses to stimulant medication and two intensities of a behavioral intervention. Behavior Modification, 16, 193–203. Abramson, L.Y., Seligman, M.E.P., & Teasdale, J. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 358–372. Achenbach, T.M. (1982). Developmental Psychopathology (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley. Achenbach, T.M. (1985). Assessment and Taxonomy of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Achenbach, T.M. (1988). Integrating assessment and taxonomy. In M. Rutter, A.H. Tuma, & I. S. Lann (Eds.), Assessment and Diagnosis in Child Psychopathology (pp. 300–343). New York: Guilford. 300 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall Achenbach, T.M., & Edelbrock, C. (1978). The classification of child psychopathology: A review and analysis of empirical efforts. Psychological Bulletin, 85, 1275–1301. Achenbach, T.M. & McConaughy, S.H. (1987). Empirically-based Assessment of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology: Practical Applications. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Anastopoulos, A.D. & Barkley, R.A. (1992). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. In C.E. Walker & M.C. Roberts (Eds.), Handbook of Clinical Child Psychology (2nd ed., pp. 413–430). New York: Wiley. Anderson, J.C., Williams, S., McGee, R., & Silva, P.A. (1987). DSM-III disorders in preadolescent children. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 69–76. Andrews, J.A. & Lewinsohn, P.M. (1992). Suicidal attempts among older adolescents: Prevalence and co-occurrence with psychiatric disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 655–662. Asarnow, J.R., Carlson, G.A., & Guthrie, D. (1987). Coping strategies, self-perceptions, hopelessness, and perceived family environments in depressed and suicidal children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 361–366. August, G.J., Realmuto, G.M., MacDonald, A.W.-III, Nugent, S.M., & Crosby, R. (1996). Prevalence of ADHD and comorbid disorders among elementary school children screened for disruptive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 571–595. Baer, R.A. & Nietzel, M.T. (1991). Cognitive and behavioral treatment of impulsivity in children: A meta-analytic review of the outcome literature. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 20, 400–412. Barkley, R.A. (1981). Hyperactive Children: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press. Barkley, R.A. (1990). Attention-deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press. Barrett, P., Dadds, M., & Rapee, R. (1996). Family treatment of child anxiety: A controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 333–342. Barrios, B.A. & Hartmann, D.P. (1988). Fears and anxieties. In E.J. Mash & L.G. Terdal (Eds.), Behavioral Assessment of Childhood Disorder (pp. 196–264). New York: Guilford Press. Bates, J.E., Bayles, K., Bennett, D.S., Ridge, B. & Brown, M.M. (1991). Origins of externalizing behavior problems at eight years of age. In D.J Pepler & K.H. Rubin (Eds.), The Development and Treatment of Childhood Aggression. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Baum, J.G., Dark, H.B., McCarthy, W., Sandier, J., & Carpenter, R. (1986). An analysis of the acquisition and generalization of social skills in troubled youths: Combining social skills training, cognitive self-talk, and relaxation procedures. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 8, 1–27. Beardslee, W.R., Wright, E., Rothberg, P.C., Salt, P., & Versage, E. (1996). Response of families to two preventive intervention strategies: Long-term differences in behavior and attitude change. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 774–782. Beck, A.T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, Experimental, and Theoretical Aspects. New York: Harper & Row. Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 301 Beck, A.T. (1976). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. New York: International Universities Press. Beck, A.T., Rush, A.J., Shaw, B.F., & Emery G. (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford. Benjamin, R.S., Costello, E.J., & Warren, M. (1990). Anxiety disorders in a pediatric sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 4, 293–316. Bernstein, G.A., & Borchardt, C.M. (1991). Anxiety disorders of childhood and adolescents: A critical review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 519–532. Biederman, J. (1987). Clonazepam in the treatment of prepubertal children with panic-like symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 48, 38–41. Biederman, J., Faraone, S., Milberger, S., Curtis, S., Chen, L., Marrs, A., Oulette, C., Moore, P. & Spencer, T. (1996a). Predictors of persistence and remission of ADHD into adolescence: Results from a four-year prospective follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 343–351. Biederman, J., Faraone, S., Milberger, S., & Guite, J. (1996b). A prospective 4-year follow-up study of attention-deficit hyperactivity and related disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53, 437–446. Biederman, J., Newcorn, J., & Sprich, S. (1991). Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 564–577. Black, B. & Robbins, D. R. (1990). Panic disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 29, 36–44. Bloomquist, M.L., August, G.J., & Ostrander, R. (1991). Effects of a school-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for ADHD children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 19, 591–605. Boldizar, J.P., Perry, D.G., & Perry, L.C. (1989). Outcome values and aggression. Child Development, 60, 571–579. Brady, E. & Kendall, P.C. (1992). Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 244–255. Braswell, L. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral groups for children manifesting ADHD and other disruptive behavioral disorders. Special Services in the Schools, 8, 91–117. Brennan, P., Mednick, S., & Kandel, E. (1991). Congenital determinants of violent and property offending. In D.J. Pepler & K.H. Rubin (Eds.), The Development and Treatment of Childhood Aggression (pp. 81–92). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Brent, D.A., Roth, C.M., Holder, D.P., Kolko, D.J., Birmaher, B., Johnson, B.A., & Schweers, J.A. (1996). Psychosocial interventions for treating adolescent suicidal depression: A comparison of three psychosocial interventions. In E.D. Hibbs & P.S. Jensen (Eds.), Psychosocial Treatments for Child and Adolescent Disorders (pp. 187–206). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Brown, R.T., Wynne, M.E., & Medenis, R. (1985). Methylphenidate and cognitive therapy: A comparison of treatment approaches with hyperactive boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 13, 69–87. Camp, B.W., & Bash, M.A. (1981). Think Aloud: Increasing Social and Cognitive Skills – A Problem-solving Program for Children. Champaign, IL: Research Press. Camp, B.W., Blom, G.E., Herbert, F., & Van Doorninck, W.J. (1977). “Think Aloud”: A program for developing self-control in young aggressive boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 5, 157–169. 302 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall Clarke, G.N., Hawkins, W., Murphy, M., Sheeber, L.B., Lewinsohn, P.M., & Seeley, J.R. (1995). Targeted prevention of unipolar depressive disorder in an at-risk sample of high school adolescents: A randomized trial of a group cognitive intervention. Journal of American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 312–321. Coats, K.I. (1979). Cognitive self-instructional training approach for reducing disruptive behavior of young children. Psychological Reports, 44, 127–134. Coie, J.D., Dodge, K.A., & Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557–570. Cole, D.A. (1991). Preliminary support for a competency-based model of depression in children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 185–193. Cook, W., Asarnow, J., Goldstein, M., Marshall, V., & Weber, E. (1990). Mother–child dynamics in early-onset depression and childhood schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 2, 71–84. Costello, E.J., Costello, A.J., Edelbrock, C., Burns, B.J., Dulcan, M.K., Brent, D., & Janiszewski, S. (1988). Psychiatric disorders in pediatric primary care: Prevalence and risk factors. Archives of General Psychiatry, 45, 1107–1116. Craske, M.G. (1988). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder. In A.J. Francis & R.E. Hales (Eds.), American Psychiatric Press Review of Psychiatry, (vol. 7., pp. 121–137) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Crick, W.R. & Dodge, K.A. (1996). Social information-processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Development, 67, 993–1002. Curry, J.F. & Craighead, W.E. (1990). Attributional style in clinically depressed and conduct disordered adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 58, 109–116. Dadds, M.R. & Barrett, P.M. (1996). Family processes in child and adolescent anxiety and depression. Behavior Change, 13, 231–239. Deblinger, E., McLeer, S.V., & Henry, D. (1990). Cognitive behavioral treatment for sexually abused children suffering post-traumatic stress: Preliminary findings. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 29, 747–752. Deluty, R.H. (1981). Alternative-thinking ability of aggressive, assertive and submissive children. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 5, 309–312. Dodge, K.A. (1980). Social cognition and children’s aggressive behavior. Child Development, 51, 162–170. Dodge, K.A. (1986). A social information processing model of social competence in children. In M. Perimutter (Ed.), Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology (vol. 18, pp. 77–125). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Dodge, K.A., Lochman, J.E., Hamish, J.D., Bates, J.E., Petit, G.S. (1997). Reactive and proactive aggression in school children and psychiatrically impaired chronically assaultive youth. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 37–51. Dodge, K.A. & Newman, J.P. (1981). Biased decision-making processes in aggressive boys. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 90, 375–379. Dumas, J.E., Neese, D.E., Prinz, R.J., & Blechman, E.A. (1996). Short-term stability of aggression, peer rejection, and depressive symptoms in middle childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 105–119. D’Zurilla, T.J. (1986). Problem-solving Therapy: A Social Competence Approach to Clinical Intervention. New York: Springer. D’Zurilla, T.J. & Goldfried, M.R. (1971). Problem-solving and behavior modification. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 73, 107–126. Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 303 Eisen, A.R. & Silverman, W.K. (1993). Should I relax or change my thoughts? A preliminary examination of cognitive therapy, relaxation training, and their combination with overanxious children. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 7, 265–279. Erdley, C.A. & Asher, S.R. (1996). Children’s social goals and self-efficacy perceptions as influences on their responses to ambiguous provocation. Child Development, 67, 1329–1344. Erhardt, D. & Hinshaw, S.P. (1994). Initial sociometric impressions of attentiondeficit hyperactivity disorder comparison boys: Predictions from social behaviors and nonbehavioral variables. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 833–842. Eron, L.D., Huesmann, L.R., Dubow, E., Romanoff, R. & Yarmel, P.W. (1987). Aggression and its correlates over 22 years. In D.H. Crowell, I.M. Evans, & C.R. O’Donnell (Eds.): Childhood Aggression and Violence. New York: Plenum Publishing. Estrada, A.U. & Pinsof, W.M. (1995). The effectiveness of family therapies for selected behavioral disorders of childhood. Special issue: The effectiveness of marital and family therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 21, 403–440. Etscheidt, S. (1991). Reducing aggressive behavior and improving self-control: A cognitive-behavioral training program for behaviorally disordered adolescents. Behavioral Disorders, 16, 107–115. Fairbank, J.A. & Keane, T.M. (1982). Flooding for combat-related stress disorders: Assessment of anxiety reduction across traumatic memories. Behavior Therapy, 13, 499–510. Feehan, M., McGee, R., & Williams, S.M. (1993). Mental health disorders from age 15 to age 18 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 1118–1126. Feindler, E.L. (1991). Ideal treatment package for children and adolescents with anger disorders. In H. Kassinove (Ed.), Anger Disorders: Definition, Diagnosis and Treatment. Series in Clinical and Community Psychology (pp. 173–195). Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. Feindler, E.L., Ecton, R.B., Kingsley, D., & Dubey, D.R. (1986). Group anger-control training for institutionalized psychiatric male adolescents. Behavior Therapy, 17, 109–123. Fergusson, D.M., Horwood, L.J., & Lynskey, M.T. (1993). Prevalence and comorbidity of DSM-III-R diagnoses in a birth cohort of 15 year olds. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 1127–1134. Fergusson, D.M., Lynskey, M.T., & Horwood, L.J. (1996). Factors associated with continuity and changes in disruptive behavior patterns between childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 533–553. Fisman, S.N. & Walsh, L. (1994). Obsessive-compulsive disorder and fear of AIDS contamination in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 349–353. Flannery-Schroeder, E., Henin, A., & Kendall, P.C. (1996). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of internalising disorders in youth. Behaviour Change, 13, 207–222. Foa, E.B., Steketee, G.S., & Ozarow, B.J. (1985). Behavior therapy with obsessivecompulsives: From theory to treatment. In M. Mavissakalian (Ed.), Obsessive-compulsive Disorders: Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments. New York: Plenum Press. 304 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall Forehand, R.E. & McMahon, R.J. (1981). Helping the Non-Compliant Child: A Clinician’s Guide to Parent Training. New York: Guilford Press. Fox, J.E. & Houston, B.K. (1981). Efficacy of self-instructional training for reducing children’s anxiety in an evaluative situation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 19, 509–515. Frank, E. & Stewart, B.D. (1983). Physical aggression: Treating the victims. In E.A. Blechman (Ed.), Behavior Modification with Women. New York: Guilford Press. Frankel, F., Myatt, R., & Cantwell, D.P. (1995). Training outpatient boys to conform with the social ecology of popular peers: Effects on parent and teacher ratings. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 24, 300–310. Frederick, B.P. & Olmi, D.J. (1994). Children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A review of the literature on social skills deficits. Psychology in the Schools, 31, 288–296. Garrison, C.Z., Jackson, K.L., Marsteller, F., McKeown, R., & Addy, C. (1990). A longitudinal study of depressive symptomatology in young adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 29, 581–585. Garrison, S.R. & Stolberg, A.L. (1983). Modification of anger in children by affective imagery training. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 11, 115–130. Gillham, J.E., Reivich, K.J., Jaycox, L.H., & Seligman, M.E.P. (1995). Prevention of depressive symptoms in schoolchildren: Two-year follow-up. Psychological Science, 6, 343–351. Ginsburg, G. S., Silverman, W. K., & Kurtines, W. K. (1995). Family involvement in treating children with phobic and anxiety disorders: A look ahead. Clinical Psychology Review, 15, 457–473. Gotlib, I.H. & Hammen, C.L. (1992). Psychological Aspects of Depression: Toward a Cognitive-Interpersonal Integration. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Gotlib, I.H., Lewinsohn, P.M., & Seeley, J.R. (1995). Symptoms versus a diagnosis of depression: Differences in psychosocial functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 90–100. Hagopian, L.P., Weist, M.D., & Ollendick, T.H. (1990). Cognitive-behavior therapy with an 11-year-old girl fearful of AIDS infection, other diseases, and poisoning: A case study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 4, 257–265. Hawkins, J.D., Jenson, J.M., Catalano, R.F., & Wells, E.A. (1991). Effects of a skills training intervention with juvenile delinquents. Research on Social Work Practice, 1, 107–121. Hayward, C., Killen, J.D., & Taylor, C.B. (1989). Panic attacks in young adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 146, 1061–1062. Heitkemper, T., Layne, C., & Sullivan, D.M. (1993). Brief treatment of children’s dental pain and anxiety. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 76, 192–194. Henggeler, S.W., Melton, G.B., & Smith, L.A. (1992). Family preservation using Multisystemic Therapy: An effective alternative to incarcerating serious juvenile offenders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 953–961. Henin, A. & Kendall, P.C. (1997). Obsessive-compulsive disorder in childhood and adolescence. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology, 19, 75–132. Hinshaw, S.P. (1987). On the distinction between attentional deficits/hyperactivity and conduct problems/aggression in child psychopathology. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 443–463. Hinshaw, S.P. (1992). Academic underachievement, attention deficits, and aggression: Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 305 Comorbidity and implications for intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 893–903. Hinshaw, S.P., Henker, B., & Whalen, C.W. (1984). Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacologic interventions for hyperactive boys: Comparative and combined effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52, 739–749. Hollingsworth, C.E., Tanguay, P.E., Grossman, L., & Pabst, P. (1980). Long-term outcome of obsessive-compulsive disorder in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 19, 134–144. Hops, H. & Lewinsohn, P.M. (1995). A course for the treatment of depression among adolescents. In K. Craig & K.S. Dobson (Eds.), Anxiety and Depression in Adults and Children. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Hops, H., Lewinsohn, P.M., Andrews, J.A., & Roberts, R.E. (1990). Psychosocial correlates of depressive symptomatology among high school students. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 19, 211–220. Horn, W.F., Ialongo, N.S., Pascoe, J.M., Greenberg, G., Packard, T., Lopez, M., Wagner, A. & Puttler, L. (1991). Additive effects of psychostimulants, parent training, and self-control therapy with ADHD children: a 9-month follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 233–240. Horn, W.F., Ialongo, N., Popovitch, S., & Peradotto, D. (1987). Behavioral parent training and cognitive-behavioral self-control therapy with ADD-H children: Comparative and combined effects. Journal of Clinical Child Psychiatry, 16, 57–68. Horne, A.M., & Sayger, T.V. (1990). Treating Conduct and Oppositional Defiant Disorders in Children. New York: Pergamon. Howard, B. & Kendall, P.C. (1996). Cognitive-behavioral family therapy for anxious children: A multiple-baseline evaluation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 20, 423–443. Huesmann, L.R. & Eron, L.D. (1984). Cognitive processes and the persistence of aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 10, 243–251. Huesmann, L.R. & Guerra, N.G. (1997). Children’s normative beliefs about aggression and aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 408–419. Huesmann, L.R. Lefkowitz, M.M., Eron, L.D., & Walder, L.O. (1984). Stability of aggression over time and generations. Developmental Psychology, 20, 1120–1134. Joiner, T.E. & Wagner, K.D. (1995). Attribution style and depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 15, 777–798. Kahn, J., Kehle, T., Jenson, W., & Clark, E. (1990). Comparison of cognitive-behavioral, relaxation, and self-modelling interventions for depression among middle-school students. School Psychology Review, 19, 235–238. Kane, M.T. & Kendall, P. C. (1989). Anxiety disorders in children: A multiple-baseline evaluation of a cognitive-behavioral treatment. Behavior Therapy, 20, 499–508. Kanfer, F., Karoly, P., & Newman, A. (1975). Reduction of children’s fear of the dark by competence-related and situational threat-related verbal cues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 251–258. Kashani, J.H., Cantwell, D.P., Shekim, W.O., & Reid, J.C. (1982). Major depressive disorder in children admitted to an inpatient community mental health center. American Journal of Psychiatry, 143, 348–350. Kashani, J.H., Carlson, G.A., Beck, N.C., Hoeper, E.W., Corcoran, C.M., McAllister, J.A., Fallahi, C., Rosenberg, T.K., & Reid, J.C. (1987). Depression, depressive 306 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall symptoms, and depressed mood among a community sample of adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 931–934. Kashani, J.H. & Orvaschel, H. (1990). A community study of anxiety in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 313–318. Kaslow, N.J., Rehm, L.P., & Siegel, A.W. (1984). Social-cognitive and cognitive correlates of depression in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 12, 605–620. Kaslow, N., Stark, K., Printz, B., Livingston, R., & Tsai, S. (1992). Cognitive Triad Inventory for Children: Development and relation to depression and anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21, 339–347. Kazdin, A.E. (1987a). Conduct Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Kazdin, A.E. (1987b). Treatment of antisocial behavior in children: Current status and future directions. Psychological Bulletin, 102, 187–203. Kazdin, A.E. (1993). Treatment of conduct disorder: Progress and directions for psychotherapy research. Development and Psychopathology, 5, 277–310. Kazdin, A.E., Bass, D., Siegel, T., & Thomas, C. (1989). Cognitive-behavioral therapy and relationship therapy in the treatment of children referred for antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, 522–535. Kazdin, A.E., Esveldt-Dawson, K., French, N.H., & Unis, A.S. (1987). Problem-solving skills training and relationship therapy in the treatment of antisocial child behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 76–85. Kazdin, A.E., French, N.H., Unis, A.S., & Esveldt-Dawson, K. (1983). Assessment of childhood depression: Correspondence of child and parent ratings. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychology, 22, 157–164. Kazdin, A.E., Siegel, T.C., & Bass, D. (1992). Cognitive problem-solving skills training and parent management training in the treatment of antisocial behavior in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 733–740. Kazdin, A.E. & Weisz, J.R. (1998). Identifying and developing empirically supported child and adolescent treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 19–36. Kearney, C.A. & Silverman, W.K. (1990). Treatment of an adolescent with obsessivecompulsive disorder by alternating response prevention and cognitive therapy: An empirical analysis. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 21, 39–47. Kendall, P.C. (1985). Toward a cognitive-behavioral model of child psychopathology and a critique of related interventions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 13, 357–375. Kendall, P.C. (1990). Coping Cat Workbook. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing. Kendall, P.C. (1991). Guiding theory for therapy with children and adolescents. In P.C. Kendall (Ed.), Child and Adolescent Therapy: Cognitive-behavioral Procedures (pp. 3–22). New York: Guilford Press. Kendall, P.C. (1992). Stop and Think Workbook. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing. Kendall, P.C. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral strategies with youth: Guiding theory, current status, and emerging developments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 235–247. Kendall, P.C. (1994). Treating anxiety disorders in children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 100–110. Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 307 Kendall, P.C. & Bacon, S.F. (1988). Cognitive behavior therapy. In D.B. Fishman, F. Rotgers, & C.M. Franks (Eds.), Paradigms in Behavior Therapy: Present and Promise (pp. 141–167). New York: Springer Publishing. Kendall, P.C., & Braswell, L. (1982). Cognitive-behavioral self-control therapy for children: A components analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50, 672–689. Kendall, P.C. & Braswell, L. (1985). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy with Impulsive Children. New York: Guilford Press. Kendall, P.C. & Braswell, L. (1993). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy with Impulsive Children (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. Kendall, P.C. & Chansky, T.E. (1991). Considering cognition in anxiety-disordered children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 5, 167–185. Kendall, P.C. Chansky, T.E., Kane, M.T., Kirn, R., Kortlander, E., Ronan, K.R., Sessa, F.M., & Siqueland, L. (1992). Anxiety Disorders in Youth: Cognitive Behavioral Interventions. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Kendall, P.C., Flannery-Schroeder, E.C., Panichelli-Mindel, S., Southam-Gerow, M., Henin, A., & Warman, M. (1997). Therapy for youths with anxiety disorders: A second randomzed clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 366–380. Kendall, P.C. & Grove, W. (1988). Normative comparisons in therapy outcome research. Behavioral Assessment, 10, 147–158. Kendall, P.C., & Ingram, R.E. (1989). Cognitive-behavioral perspectives: Theory and research on depression and anxiety. In P.C. Kendall & D. Watson (Eds.), Anxiety and Depression: Distinctive and Overlapping Features (pp. 27–53). New York: Academic Press. Kendall, P. C., Kane, M., Howard, B., & Siqueland, L. (1990). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxious Children: Treatment Manual. Available from the author, Temple University, Department of Psychology, Philadelphia, PA 19122. Kendall, P.C. & MacDonald, J.P. (1993). Cognition in the psychopathology of youth and implications for treatment. In K.S. Dobson & P.C. Kendall (Eds.), Psychopathology and Cognition. New York: Academic Press. Kendall, P.C. & Reber, M. (1987). Cognitive training in treatment of hyperactivity in children. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 296. Kendall, P.C., Reber, M., McLeer, S., Epps, J., & Ronan, K.R. (1990). Cognitivebehavioral treatment of conduct-disordered children. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 279–297. Kendall, P.C., Ronan, K.R., & Epps, J. (1991). Aggression in children/adolescents: Cognitive-behavioral treatment perspectives. In D.J. Pepler & K.H. Rubin (Eds.), The Development and Treatment of Childhood Aggression (pp. 341–360). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Kendall, P.C. & Siqueland, L. (1989). Child and adolescent therapy. In A.M. Nezu & C.M. Nezu (Eds.), Clinical Decision Making in Behavior Therapy: A Problem-solving perspective. Champaign, IL: Research Press. Kendall, P.C., & Southam-Gerow, M.A. (1996). Long term follow-up of a cognitivebehavioral therapy for anxiety-disordered youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 724–730. Kendall, P.C., Stark, K.D., & Adam, T. (1990). Cognitive deficit or cognitive distortion in childhood depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 18, 255–270. 308 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall Kettlewell, P.W., & Kausch, D.F. (1983). The generalization of the effects of a cognitive-behavioral treatment program for aggressive children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 11, 101–114. Kilpatrick, D.G., Veronen, L.J., & Resick, P.A. (1982). Psychological sequelae to rape: Assessment and treatment strategies. In D.M. Doleys, R.L. Meredith, & A.R. Ciminero (Eds.), Behavioral Medicine: Assessment and Treatment Strategies (pp. 473–497). New York: Plenum Press. King, N.J., Hamilton, D.I., & Ollendick, T.H. (1988). Children’s Phobias: A Behavioral Perspective. Chichester: Wiley. King, N.J. & Ollendick, T.H. (1989). Children’s anxiety and phobic disorders in school settings: Classification, assessment, and intervention issues. Review of Educational Research, 59, 431–470. Kovacs, M. (1996). Presentation and course of major depressive disorder during childhood and later years of the life span. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 705–715. Kovacs, M., Feinberg, T.L., Crouse-Novak, M., Paulauskas, S.L., Pollock, M., & Finkelstein, R. (1984a). Depressive disorders in childhood: I. A longitudinal prospective study of characteristics and recovery. Archives of General Psychiatry, 41, 229–237. Kovacs, M., Feinberg, T.L., Crouse-Novak, M., Paulauskas, S.L., Pollock, M., & Finkelstein, R. (1984b). Depressive disorders in childhood: II. A longitudinal prospective study of the risk for a subsequent major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 41, 643–649. Kroll, L., Harrington, R., Jayson, D., Fraser, J., & Gowers et al. (1996). Pilot study of continuation cognitive-behavioral therapy for major depression in adolescent psychiatric patients. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 1156–1161. Landau, S. & Moore, L.A. (1991). Social skill deficits in children with attentiondeficit hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Review, 20, 235–251. Larson, R.W., Raffaelli, M., Richards, M.H., Ham, M., & Jewell, L. (1990). Ecology of depression in late childhood and early adolescence: A profile of daily states and activities. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 92–102. Leitenberg, H., Yost, L.W., & Carroll-Wilson, M. (1986). Negative cognitive errors in children: Questionnaire development, normative data, and comparisons between children with and without self-reported symptoms of depression, low self-esteem and evaluation anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 528–536. Lewinsohn, P.M., Clarke, G.N., Hops H., & Andrews, J. (1990). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for depressed adolescents. Behavior Therapy, 21, 385–401. Lewinsohn, P.M., Clarke, G.N., & Rohde, P. (1994). Psychological approaches to the treatment of depression in adolescents. In W.M. Reynolds & H.F. Johnston (Eds.), Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents (pp. 309–344). New York: Plenum Press. Lewinsohn, P.M., Clarke, G.N., Rohde, P., Hops, H., & Seeley, J.R. (1996). A course in coping: A cognitive-behavioral approach to the treatment of adolescent depression. In E.D. Hibbs & P.S. Jensen (Eds.), Psychosocial Treatments for Child and Adolescent Disorders (pp. 109–135). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Lewinsohn, P.M., Hops, H., Roberts, R.E., Seeley, J.R., & Andrews, J.A. (1993). Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 309 Adolescent psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 133–144. Lochman, J.E. (1985). Effects of different treatment lengths in cognitive behavioral interventions with aggressive boys. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 16, 45–56. Lochman, J.E. (1992). Cognitive-behavioral interventions with aggressive boys: Threeyear follow-up and preventive effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 426–432. Lochman, J.E., Burch, P.R., Curry, J.F., & Lampron, L.B. (1984). Treatment and generalization effects of cognitive-behavioral and goal-setting interventions with aggressive boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52, 915–916. Lochman, J.E., & Lampron, L.B. (1986). Situational social problem-solving skills and self-esteem of aggressive and nonaggressive boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 14, 605–617. Lochman, J.E., Lampron, L.B., Burch, P.R., & Curry, J.F. (1985). Client characteristics associated with behavior change for treated and untreated aggressive boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 13, 527–538. Lochman, J.E., Lampron, L.B., Gemmer, T.C., Harris, R., & Wyckoff, G.M. (1989). Teacher consultation and cognitive behavioral interventions with aggressive boys. Psychology in the Schools, 26, 179–188. Lochman, J.E. & Lenhart, L.A. (1993). Anger coping intervention for aggressive children: Conceptual models and outcome effects. Clinical Psychology Review, 13, 785–805. Lochman, J.E., Nelson, W.M., & Sims, S.P. (1981). A cognitive behavioral program for use with aggressive children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 10, 146–148. Lochman, J.E., White, K.J., & Wayland, K.K. (1991). Cognitive-behavioral assessment and treatment with aggressive children. In P.C. Kendall (Ed.), Child and Adolescent Therapy: Cognitive-Behavioral Procedures (pp. 25–65). New York: Guilford. Lyons, J.A. (1988). Posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: A review of the literature. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 8, 349–356. Maag, J.W., Parks, B.T., & Rutherford, B.B. (1988). Generalization and behavior covariation of aggression in children receiving stress inoculation therapy. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 10, 29–47. Mahoney, M.J. (1974). Cognition and Behavior Modification. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger. March, J.S. (1995). Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A review and recommendations for treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 7–18. March, J.S., Mulle, K., & Herbel, B. (1994). Behavioral psychotherapy for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: An open trial of a new protocol-driven treatment package. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 333–341. Meichenbaum, D. (1977). Cognitive-Behavior Modification: An Integrative Approach. New York: Plenum Press. Meichenbaum, D. (1986). Stress Inoculation Training. New York: Pergamon Press. Meichenbaum, D. & Goodman, J. (1971). Training impulsive children to talk to themselves: A means of developing self-control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 77, 115–126. 310 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall Melamed, B.G. & Siegel, L.J. (1975). Reduction of anxiety in children facing hospitalization and surgery by use of filmed modelling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 511–521. Milich, R. & Dodge, K.A. (1984). Social information processing in child psychiatric populations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 12, 471–490. Miller, G.E., London, L.H., & Prinz, R.J. (1991). Understanding and treating serious childhood behavior disorders. Family and Community Health, 14, 33–41. Miller, G.E. & Prinz, R.J. (1990). Enhancement of social learning family interventions for childhood conduct disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 291–307. Miller, L.S. (1994). Preventive interventions for conduct disorders: A review. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 3, 405–420. Moreau, D., & Weissman, M.M. (1992). Panic disorder in children and adolescents: A review. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 1306–1314. Moreau, D., Weissman, M.M., & Warner, V. (1989). Panic disorder in children at high risk for depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 146, 1059–1060. Morris, R.J. & Kratchowill, T.R. (1983). Treating Children’s Fears and Phobias: A Behavioral Approach. New York: Pergamon Press. Nathan, W.A. (1992). Integrated multimodal therapy of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 56, 283–312. Nelson, W.M. & Finch, A.J. (1996). “Keeping Your Cool”. The Anger Management Workbook. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing. Nezu, A.M., Nezu, C.M., & Perri, M.G. (1989). Problem-solving Therapy for Depression: Theory, Research, and Clinical Guidelines. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Ollendick, T.H. (1995). Cognitive behavioral treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia in adolescents: A multiple baseline design analysis. Behavior Therapy, 26, 517–531. Olweus, D. (1979). Stability of aggressive reaction patterns in males: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 86, 852–875. Olweus, D. (1984). Stability in aggressive and withdrawn, inhibited behavior patterns. In R.J. Blanchard & D.C. Blanchard (Eds.), Advances in the Study of Aggression (vol. 1, pp. 103–137). Orlando, FL: Academic Press. Parker, J.G., & Asher, S.R. (1987). Peer relations and later personal adjustment: Are low-accepted children at risk? Psychological Bulletin, 102, 357–389. Patterson, G.R. (1976). Living with Children: New Methods for Parents and Teachers. Champaign, IL: Research Press. Patterson, G.R. (1982). Coercive Family Process. Eugene, OR: Castalia Publishing Company. Patterson, G.R., Reid, J.B., Jones, R.R., et al. (1975). A Social Learning Approach to Family Intervention. I. Families with Aggressive Children. Eugene, OR: Castalia Publishing Company. Pennington, B.F., Groisser, D., & Welsh, M.C. (1993). Contrasting cognitive deficits in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder versus reading disability. Developmental Psychology, 29, 511–523. Perry, D.G., Perry, L.C., & Rasmussen, P. (1986). Cognitive social learning mediators of aggression. Child Development, 57, 700–711. Peterson, L. & Shigetomi, C. (1981). The use of coping techniques to minimize anxiety in hospitalized children. Behavior Therapy, 12, 1–14. Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 311 Piacentini, J., Gitow, A., Jaffer, M., Graae, F., & Whitaker, A. (1994). Outpatient behavioral treatment of child and adolescent obsessive compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 8, 277–289. Pincus, J.H. (1987). A neurological view of violence. In D.H. Crowell, I.M. Evans, & C.R. O’Donnell (Eds.), Childhood Aggression and Violence: Sources of Influence, Prevention, and Control (pp 53–73). New York: Plenum. Pulkkinen, L. (1996). Proactive and reactive aggression in early adolescence as precursors to anti- and prosocial behavior in young adults. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 241–257. Rabiner, D.L., Lenhart, L., & Lochman, J.E. (1990). Automatic versus reflective social problem solving in relation to children’s sociometric status. Developmental Psychology, 26, 1010–1016. Raine, A., Brennan, P., & Mednick, S.A. (1994). Birth complications combined with early maternal rejection at age 1 year predispose to violent crime at age 18 years. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 984–988. Reynolds, W.M. & Coats, K.I. (1986). A comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and relaxation training for the treatment of depression in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 653–660. Richard, B.A. & Dodge, K.A. (1982). Social maladjustment and problem solving in school-aged children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50, 226–233. Ronan, K.R., Kendall, P.C., & Rowe, M. (1994). Negative affectivity in children: Development and validation of a self-statement questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 18, 509–528. Rubin, K.H. (1985). Socially withdrawn children: An “at risk” population? In B. Schneider, K.H. Rubin, & J. Ledingham (Eds.), Children’s Peer Relations: Issues in Assessment and Intervention (pp. 125–140). New York: Springer-Verlag. Rutter, M.R., Tizard, J., & Whitmore, K. (1970). Education, Health, and Behavior. London: Longmans. Sanford, M., Szatmari, P., Spinner, M., Munroe-Blum, H., Jamieson, E., Walsh, C. & Jones, D. (1995). Predicting the one-year course of adolescent major depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 1618–1628. Shah, F. & Morgan, S.B. (1996). Teacher’s ratings of social competence of children with high versus low levels of depressive symptoms. Journal of School Psychology, 34, 337–349. Sheehan, D.V., Sheehan, K.E., & Minichiello, W.E. (1981). Age of onset of phobic disorders: A reevaluation. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 22, 544–553. Sheridan, S.M., Dee, C.C., Morgan, J.C., McCormick, M.E., & Walker D. (1996). A multimethod intervention for social skills deficits in children with ADHD and their parents. School Psychology Review, 25, 57–76. Singer, L.T., Ambuel, B., Wade, S., & Jaffe, A.C. (1992). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of health-impairing food phobias in children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 847–852. Slaby, R.G. & Guerra, N.G. (1988). Cognitive mediators of aggression in adolescent offenders: 1. Assessment. Developmental Psychology, 24, 580–588. Southam-Gerow, M.A., Henin, A., Chu, B., Marrs, A., & Kendall, P.C. (1997). Cognitive-behavioral therapy with children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 6, 111–136. 312 Aude Henin, Melissa Warman, and Philip C. Kendall Spencer, T., Biederman, J., Wilens, T., Harding, M., O’Donnell, D., & Griffin, S. (1996). Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder across the life cycle. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 409–432. Spivack, G. & Shure, M.B. (1974). Social Adjustment of Young Children: A Cognitive Approach to Solving Real-Life Problems. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Stanley, M.A., & Turner, S.M. (1995). Current status of pharmacological and behavioral treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behavior Therapy, 26, 163–186. Stark, K.D., Brookman, C.S., & Frazier, R. (1990). A comprehensive school-based, treatment program for depressed children. School Psychology Quarterly, 5, 111–140. Stark, K.D. & Kendall, P.C. (1996). Treating Depressed Children: Therapist Manual for “Taking Action”. Philadelphia: Workbook Publishing. Stark, K.D., Reynolds, W., & Kaslow, N. (1987). A comparison of the relative efficacy of self-control therapy and a behavioral problem-solving therapy for depression in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 15, 91–113. Stark, K.D., Rouse, L.W., & Livingston, R. (1991). Treatment of depression during childhood and adolescence: Cognitive-behavioral procedures for the individual and family. In P.C. Kendall (Ed.), Child and Adolescent Therapy: Cognitive-behavioral procedures (pp. 165–206). New York: Guilford Press. Staub, E. (1996). Cultural-societal roots of violence: The example of genocidal violence and of contemporary youth violence in the United States. American Psychologist, 51, 117–132. Strauss, C.C., Forehand, R., Smith, K., & Frame, C.L. (1986). The association between social withdrawal and internalizing problems of children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 14, 525–535. Strauss, C.C., Last, C.G., Hersen, M., & Kazdin, A.E. (1988). Association between anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 16, 57–68. Szatmaris P., Offord, D.R., & Boyle, M.H. (1989). Ontario Child Health Study: Prevalence of attention-deficit disorders with hyperactivity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 30, 219–230. Thyer, B.A., Parris, R.T., Curtis, G.C., Nesse, R.M., & Cameron, O.G. (1985). Ages of onset of DSM-III anxiety disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 26, 113–122. Tolan, P.H., Guerra, N.G., & Kendall, P.C. (1995). A developmental-ecological perspective on antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: Toward a unified risk and intervention framework. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 579–584. Tremblay, R.E., Pihl, R.O., Vitaro, F.,& Dobkin, P.L. (1994). Predicting early onset of male antisocial behavior from preschool behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 732–739. van der Ploeg-Stapert, J.D. & van der Ploeg, H.M. (1986). Behavioral group treatment of test anxiety: An evaluation study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 17, 255–259. Webster-Stratton, C. (1994). Advancing videotape parent training: A comparison study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 583–593. Webster-Stratton, C. & Hammond, M. (1997). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: A comparison of child and parent training interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 93–109. Cognitive behavioural therapy with children and adolescents 313 Wender, P.H. (1987). The Hyperactive Child, Adolescent, and Adult. New York: Oxford University Press. Whalen, C.K. & Henker, B. (1991). Therapies for hyperactive children: Comparisons, combinations, and compromises. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 126–137. Whitaker, A., Johnson, J., Shaffer, D., Rapopport, J.L., Kalikow, K., Walsh, B.T., Davies, M., Braiman, S., & Dolinsky, A. (1990). Uncommon troubles in young people: Prevalence estimates of selected psychiatric disorders in a non-referred adolescent population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47, 487–496. Wierzbicki, M. & McCabe, M. (1988). Social skills and subsequent depressive symptomatology in children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 17, 203–208. Wilson, J.M. & Marcotte, A.C. (1996). Psychosocial adjustment and educational outcome in adolescents with a childhood diagnosis of attention deficit disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 579–587. Wolf, M.M., Braukmann, C.J., & Ramp, K.A. (1987). Serious delinquent behavior as part of a significantly handicapping condition: Cures and supportive environments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 20, 347–359. Wood, A., Harrington, R., & Moore, A. (1996). Controlled trial of a brief cognitivebehavioural intervention in adolescent patients with depressive disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 37, 737–746. This page intentionally left blank Index abandonment 56, 179, 206, 219, 224; fears related to 225 Abrahms, L. 248 Abramowitz, A. J. 298 Abramowitz, J. S. 125 abuse 207, 216; alcohol 84, 220; child 51; emotional 231; laxative 174, 176, 183–4, 185; physical 231; sexual 30, 88, 231, 286; substance 7, 9, 10, 55, 73, 84, 220, 223, 225, 280, 288 acceptance 189, 207 accidents 56, 127 accomplishment 20, 282, 289 Achenbach, T. M. 279 Activity Charts 20–1 AD (avoidant disorder) 282, 283, 287 adaptation 181; false-self 179; metabolic 182 adaptiveness 5, 11, 14, 15, 17, 19, 23, 29, 110, 194; increasing 157; ways of handling anger 64; see also RAR addiction 90 adequacy 26 ADHD (attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder) 279, 280, 296–9 adjunctive techniques 102 adolescents 195, 250, 275–313 advantages 18, 62, 63, 164, 255 aetiology 73, 175, 184 affect modulation 73, 85–6 affection 8, 225, 255 affective instability/illness 223, 287 agenda setting 14–16, 107 aggression 225, 276, 279, 291–6, 297 agitation 89 agoraphobia 97–8, 100, 102, 105, 108, 116, 118, 286; severe 104 agreements 63 alcohol 7, 57, 73, 76, 84, 220 Alcoholics Anonymous 36, 55 altruism 84 amenorrhoea 173 analgesics 73, 76 analytic psychotherapy 168 Anastiades, P. 103 Anastopoulos, A. D. 298 anger 64–5, 72, 78, 80, 99, 133, 153, 245; anxiety and 237; awareness of own 207; lack of control of 224; selfdirected 219; validated 88; vicious blaming cycle propelled by 248 Anger Coping Program 294 Angry Child mode 219 anorexia nervosa 173–4, 175, 176–7, 177–8, 179, 193; adaptation of standard procedures for 181; body weight 184, 185, 191; common problem in 189; family therapy in 194–6; self-monitoring 186 anti-convulsants 71 anticipation 100, 102, 247 antidepressants 52 antisocial behaviour 276, 291, 295, 296 anxiety 57, 65, 72, 97, 106, 111, 131, 186; absence of 75; anger and 237; anticipatory 102; associated with memories and cognition 204; automatic thoughts and 115; childhood 279, 281, 282–3, 284, 285, 297; chronic 163; cognitive distortions thought to underlie 276; cognitive therapy effective for 202; common denominator across disorders 129, 130; controlling 109, 155; elevated 99, 100; extreme 230; general 105, 117, 118; heightened 110; high levels 22, 316 Index anxiety, continued 225; induction of 112–13, 116; mild to moderate 98; non-dangerous nature of 109, 110; non-patholog- ical 110; reducing 107, 155, 156, 289; relapse prevention 220; relieved 58; schemas activated by 236; self-regulation of 110; separation 276; shifts from baseline mood to 224; symptoms 98–100, 103; youth 280–7; see also AD; eating disorders; GAD; OAD; OCD; RIA; SAD APA (American Psychiatric Association) 37, 97; see also DSM-III appraisals 117, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 204, 292; beliefs/assumptions underlying 142–3; catastrophic 99; certainty 141; cognitive 196; identifying 133–7, 143, 144; idiosyncratic 145; inaccurate 244; likelihood thought-action fusion 138–9; responsibility 137–8, 139–40, 142; self 289; threatening 106, 127 apprehension 98, 151 approval 207, 219, 250 Arntz, A. 104, 129, 137, 140, 143, 144 arousal 83, 85; anger 292, 293; autonomic 110; physiological 98, 115, 281, 293 arterial pressure 110 asceticism 191 assertiveness training 289 assessment: depression 9; personality disorders 210–12; relationships 249–55; scientific 165; suicidal risk 51, 53–5 associative therapy 104 assumptions 12, 13, 61, 111, 181, 227, 252; core 196; dysfunctional 194, 196; faulty 182; problematic 249; underlying 16, 142–3, 188, 204, 205, 246; vague 192 ATs (automatic thoughts) 11, 18, 20, 25; accessing 204, 227; anticipated outcome of 245–6; anxiety and 115; dispelling and reframing 262–3; dysfunctional 12, 262; effect of believing 24; eliciting 108; fairly accurate 17; identifying 22, 188, 259–60; linking emotions with 260–1; logic and themes of 244; negative 28, 116, 117; obvious 23; responding to 108, 115, 117; situations that trigger 117; situation-specific 12; social embarrassment 35; spouses/partners 244, 257; tracing 245; underlying schemata behind 252 attention 55, 85, 207, 225; selective 114, 139; self-focused 100; see also ADHD attitudes 179, 180, 194, 251; all-ornothing 81; characteristic 176; extreme 189; negative 71, 253; selfdestructive 178; underlying 17–18; see also Dysfunctional Attitude Scale attributions 252, 267, 277; causal 248–9, 251, 278, 288, 289; responsibility 251 autonomic nervous system 155, 281 autonomy 80, 82, 205, 250; conflicts over 191; impaired 207 auxiliary therapists 67 avoidance 97, 98, 103, 104, 112, 113–14, 204, 225; agoraphobic 100, 105, 109, 116; anxiety maintained via 167; behavioural 165, 211, 217; behaviours that reduce 107; cognitive 165, 211; decreased 236–7; effective 204; phobic 106; risk 190; schema 206, 209, 211, 219; subtle 111 awareness 201, 211, 277, 293; interoceptive 193; self 74, 191 Axis I disorders 9, 151, 201, 204, 227, 235, 236 background information 9 Baer, R. A. 297 BAI (Beck Anxiety Inventory) 113 Barkley, R. A. 298 Barlow, D. H. 105, 118 Barrett, P. 284 Baucom, D. H. 249, 250, 251, 252, 268, 269, 270 BD (bipolar disorder) 4, 71–96 BDI (Beck Depression Inventory) 10, 33, 53–4, 290 Beck, A. T. 4–5, 12, 36, 66–7, 98, 102–3, 108, 109, 118, 178, 181, 201, 202, 204, 229, 243, 244–5, 252; see also BAI; BDI; BHS; cognitive triad; DAS; Dysfunctional Attitude Scale Beck, J. S. 6–7, 22, 36; see also DTRs behavioural exercises 190, 193, 217 beliefs 26, 57, 87, 106, 142–3, 188, 216; adaptive 19, 27, 32; alternative 91, 247, 263; articulation of 189; assessed Index 111; catastrophic 116; challenging 190; conditional 227; depressotypic 288, 289; distorted 179, 246–7; experiential testing of 12; explicit emphasis on 181; irrational 243, 288; multi-level 196; nascent positive 26; negative 49, 214; problematic 90; reframing 92; relationship 245–6; tools to use to change 131; unconditional 226; underlying 10, 246, 248, 260, 261; unrealistic 243, 244, 250; verbalised 31–2; see also core beliefs; dysfunctional beliefs Bemis, K. M. 192 benign restrictions 82 Benjamin, R. S. 280 benzodiazapines 97, 105 Berchick, R. J. 102–3 BHS (Beck Hopelessness Scale) 10, 33, 54 biases 77, 81–2, 106, 246, 257; hostile attributional 292; negative 72 bibliotherapy 16, 77 binge eating 174, 177, 178, 182, 184, 185, 186, 193, 223; affective and interpersonal antecedents of 179; consuming without 190; education about 183; elimination of 176; inoculation against 187; issues that can lead to amelioration of 180; urges 182 biochemical factors: abnormalities 71, 89; changes 74; dyscontrol 73; homeostasis 73; manipulations 97 biology 97, 291 bipolar disorder see BD Birbaumer, N. 111 Birchler, G. R. 252 blame 248, 251; self 7, 11, 20, 138, 250 blood sugar 110 Blumberg, S. L. 269 blurred vision 112 bodily sensations 98–100, 101, 106, 107, 110, 238; combinations of 113; feared 111, 116, 118; interpretation of 115; uncomfortable 155 body weight 173, 176, 177, 184–7, 190, 192; attitudes towards 179, 180; homeostatic regulation of 178; need to gain 178; permanently lowering 182; unrealistic standards for 178 booster sessions 103, 118 317 boredom 57, 219, 224, 225 boundaries 215, 225, 249, 250, 251 Bourne, E. J. 22 BPD (borderline personality disorder) 65, 208, 219, 223–41 Bradbury, T. N. 251 brainstorming approach 63, 270 Braswell, L. 296 breathing 85, 106, 108; controlled 109, 117; deep and rapid 113; diaphragmatic 101, 154, 155–8, 277; retraining 101, 102, 104, 105, 114, 115, 118; see also hyperventilation breathlessness 113 Brown, G. K. 118 Brown, T. A. 105 Bruch, H. 193 bulimia nervosa 174, 175, 176–7, 178, 193–4; adaptation of standard procedures for 181; body weight 184–5; educational treatments 182; self- monitoring 186 Burnett, C. K. 249, 251 caffeine 97, 110 calm 85, 156, 158, 159, 160, 161, 237 calories 183, 184, 186–7 carbon dioxide 97, 105 cardiopulmonary problems 112 Carels, R. A. 251 Carlson, C. I. 251 Carr, A. T. 126, 129 catastrophes 106, 111, 159, 164, 165, 288; expected 245–6; see also catastrophic misinterpretation; decatastrophising catastrophic misinterpretation 98, 99–100, 101, 107, 109, 110; degree of belief in 112, 114, 116, 117; disconfirming 114; reduction of 117 treatment to correct 105 causal attributions/misattributions 248–9 causal factors: depression 5; eating disorders 175 central nervous system 73; see also autonomic nervous system; sympathetic nervous system Cerny, J. A. 105, 118 certainty 141, 191 Chambless, D. L. 98 chance 129 318 Index change 5–6, 129, 152, 209–10, 212–18, 230; affective 13; attitudinal 291, 295; behavioural 13, 190, 195, 196, 291; clinically significant 168; cognitive 106, 117; commitment or tolerance for 184; life 55, 80; motivation for 176, 184, 224; positive 14; powerful leverage for 215; resistance to 176; schematic 205 channels of input 230–1 character traits 142 characterological disorders 203, 204, 208, 211, 215, 220 checklists 10, 15, 113, 255 chest breathing 155 child abuse 51 childhood/children 205, 211, 214, 245, 250, 252, 275–313; family interventions 266 choice 57, 58, 60, 207; freedom of 52–3; rational 59 ‘chronic disease’ model 296 Clark, D. A. 98, 99, 101, 102–3, 107, 109, 119, 129 Cochran, S. 92 cognition 32, 57, 195; adaptive 166; catastrophic 100; depressogenic 289; dysfunctional 12; interview assessment of 252; levels of 226–8; maladaptive 288; negative 67, 100; non-functional 278; relationship 249–52 cognitive-affective-behavioural patterns 3 cognitive distortions 12, 16, 29, 31, 212, 262; cognitive deficiency and 275; identifying and labelling 255–8 cognitive restructuring 27, 105, 118, 176, 188–91, 267, 268, 277, 278, 288, 293; initial aim of 178 cognitive therapy 102–4, 161–7, 223–41; basic rules for homework 17–18; defining 4–5; emphasis on guided discovery approach 62; goals for 11–12, 73–87, 190; imagery and 29; limitations of 202–3; staying power of therapeutic effects of 92; structure of 86–7; suicidality and 34, 49, 67–8 cognitive triad 49, 72, 87; negative 5 cohesion 251, 288 collaboration 13, 17, 22, 35, 53, 59, 60, 63, 82, 106, 202, 203, 216, 268; disincentive to 92; facilitated 77 ‘collaborative set’ term 248 collapse 106, 110 ‘come and go’ style 138 commands 58, 65–6 comments 152 commitment 63 communications training 242, 268, 269 comordic disorders 9, 126, 285, 288, 296, 297 compensatory strategies/behaviours 7, 174, 178, 188, 212 competence 18, 36, 229, 237 compulsions see OCD computers 36–7, 269 concentration 75, 87, 88, 150 conceptualisation: anxiety 281; BD 72, 87–9; BPD 225, 226–8, 233–5, 236; childhood aggression 291; depression 8, 12, 18, 19, 35, 36; eating disorders 195; OCD 132, 133; panic disorder 97, 116, 119; personality disorders 209; suicidal behaviour 54, 56–9 conditioning 98; aversive 204 conduct disorder 291, 294, 296 confidence 22, 78, 152, 292; lack of 193 conflict avoidance 179, 196 conflicts 27, 250 confrontation 139, 214, 218; empathic 216 confusion 193 constancy 74 constructions 5; dysfunctional 6 constructivist movement 202–3 containment 81 contamination 130, 133, 140 contingencies 293, 297 continuum method 29–31, 34, 139, 142 contracts 63; verbal 91–2 contradictory behaviour 190 coping 7, 12, 26, 27, 57, 58, 71, 101, 103, 107, 114, 115, 117, 167; adaptive 159, 277; applying strategies 160; childhood anxiety 281, 282, 286; common strategy, responsibility appraisals 139–40; complete lack of resources 165; development of plans 190; effective 65, 159, 160, 161; FCT and 109; good 8; helping the child construct a template 277; interventions providing skills 151; life changes and 80; maladaptive styles of 205, 209; new responses 152; opportunity for child to practise 278; Index promising strategies 66; strained 81; successful 36, 165 core beliefs 165, 227, 230, 246; negative 7, 26; revising 26–7; rigid, dysfunctional 12 cost-benefit analysis 163 costs 3, 4, 169 countertransference 18; frustrating 19 couples 243–7, 248, 249, 252–9, 261, 264, 266 Cox, B. J. 119 Craske, M. G. 105 creativity 90 criticism 17, 19–20, 215, 219, 269; constructive 76; derogatory 218; extreme sensitivity 191; self 7 cues 85, 277; affective 293; anxiety 157, 158, 159, 160, 161; behavioural 252; early detection of 152–3; environmental 281; hostile 292; physiological 293; social 281, 292; somatic 105 cyberspace 37 cycles 91; breathing 113; negative 6, 11 Dadds, M. R. 268, 284 Daiuto, A. D. 251 danger 82, 98, 99, 127, 129, 141, 142, 143, 237; future 167; overestimation of 144, 145 DAS (Daily Activity Schedules) 84 DAS (Dyadic Adjustment Scale) 254 Dattilio, F. M. 113, 246, 249, 268 Davidson, G. C. 85 death 7, 53, 59, 100 decatastrophising 165, 190 decentring 5, 189 decision-making 57, 130, 178, 186; dayto-day 79; impulsive 72; snap 83 decision-tree model 177, 178 defeat 5 defectiveness 205, 207, 211–12, 214, 215, 218, 219 defiance 78, 230 deficiency 10 deficits 54–5; see also ADHD delinquent behaviour 294 delusion 5, 58 demoralisation 6, 33, 74 denial 20, 76, 232 dependence 191, 207, 215, 225, 230 depersonalisation 119, 219 319 depression 3–48, 72, 74, 77, 80, 103, 104, 106, 153, 296; adolescent 287; associated with memories and cognition 204; childhood 279, 288; clinical 290; cognitive distortions contributing to 256, 276; comordic 126; Freud and 201; intermittent 289; management of 267; perfection- ism and 130; reducing 118; relapse prevention 220, 291; shifts from baseline mood to 223; specific procedures for treatment of 181; suicidality and 49, 51, 56, 59, 60, 78, 89; bipolar 287–91; youth 288; see also MDD deprivation 86, 215; emotional 219 Detached Protector mode 219 deterrents to suicide 61, 62, 64, 65 detoxification 9 diabetes 3 diagnosis: ADHD 296, 297; anorexia nervosa 173; anxiety disorder 283, 284; BD 88; BPD 223–5; depression 3, 9, 287; GAD 150–1, 168; OCD 127; panic disorder 286; see also DSM-III diathesis-stress disorder 71 dieting 176, 178, 179, 180, 182–3, 189, 191 difficult cases 219–20 diffuse presentation 203 dignity 82, 85, 90 disadvantages 18, 62, 63, 127, 164, 192, 255 disappointment 83, 164, 216, 247, 248 disapproval 166 disaster 99 discomfort 207, 214 disconnection 206–7, 215 disengagement 195 disequilibrium 22 disorganisation 74, 86–7 disputation 62 disruptive behaviour 294 distancing methods 162, 213, 225 distractibility 74, 86–7 distraction 108 distress 7, 10, 24, 27, 36, 66, 129, 134; alleviating and preventing 9; emotional 127, 182; future 13; identification of sources of 67; images associated with 16, 29; lessons learned during moments of 75; relationship 244, 247, 248, 252, 257, 266; significant 150 320 Index distrust 88, 225 divisiveness 67 dizygotic twins 51 dizziness 106, 107, 112, 113, 116, 118, 119 Dodge, K. A. 292 downward-arrow technique 134–5, 137, 141–2, 245–6, 252 downward spirals 81 drinking 7, 55 drugs 54, 57, 220 Dryden, W. 266, 267 DSM-III (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders): anxiety 150–1, 168; BPD 223, 224–5; depression 289, 290; eating disorders 173–4; panic disorder 97, 103, 109, 118–19; personality disorders 201, 203, 220 DTRs (Daily/Dysfunctional Thought Records) 19, 24–6, 80, 115, 117, 237, 260 dying 113, 118, 128 dynamic models 179 dysfunction 66, 82, 175, 195, 205, 227, 237, 297; cognitive-processing 276; family 295; long-term, serious 71; marital/relationship 243, 244, 248; see also assumptions; cognition; constructions; dysfunctional beliefs; DTR; images; interpret- ations; thoughts Dysfunctional Attitude Scale 165–6 dysfunctional beliefs 5, 8, 14, 18, 19, 32, 36, 117; CT’s strength in assessing and modifying 91; examining evidence for and against 188–9; identifying and correcting 181; relationships 244 dysphoria 21, 72, 76 dyspnoea 118 dysthmia 287 early warning signs 74, 76, 77 eating disorders 130, 173–200, 220; see also anorexia; bulimia eating patterns/habits 74, 84, 110, 186, 190, 194; regular 188; suboptimal 73 education 73, 74–7, 109, 110–11, 181–4; affective 277, 281, 293, 296; schema 212, 228 Ehlers, A. 111 Eidelson, R. J. 244, 249 Eisen, A. R. 282, 283 Ellis, A. 190, 243 Ellis, T. 34 embarrassment 35 Emery, G. 245 emotions 13, 25, 99, 115, 161, 201, 202, 226, 236, 252; anxious 156; ATs and 260–1, 262; difficulties in expressing 193; family 266; inability to identify and respond to 193; intense 85, 86; maladaptive 181; negative 152, 213, 243, 253; pent-up 219; previously avoided 211; stabilising 227; thoughts influence 110; tracing 245; viewed as informative 203 empathy 8, 90, 91, 215, 216, 269; accurate 88 empiricism 21, 22–4, 92; collaborative 131, 132, 202 empowerment 73, 215, 245 emptiness 219, 224 EMS (early maladaptive schemas) 204–5, 210, 211 enactment 255 encouragement 33, 35, 63 Endler, N. S. 119 engulfment 179 enjoyable activities 75 enmeshment 179, 207 enthusiasm 77, 78 entitlement 219 environmental situations 9, 67, 71 epilepsy 112 Epstein, N. 195, 244, 249, 250, 251, 252, 266, 267, 268, 269, 270 Erikson, E. H. 229–30 ERP (exposure and response prevention) 125–7, 131, 145 erratic behaviour 76, 81 escape 100, 106, 112, 113–14; anxiety maintained via 167 ethics 58, 208 euphoria 85 Everson, S. A. 56 evidence 26, 67, 77, 88, 109, 128, 137, 162; contradictory 213; countering 167; examining 188–9, 190; idiosyncratic 117; rational evaluation of 195; substantiating 246, 256; weighing 263–4 Ewald, L. S. 191 exaggerations 72 Index excitement 57, 65, 85, 99 exercise 10, 22, 99, 108, 113; excessive 174; repeated 155 expectations 9, 61, 64, 229, 292; apprehension 151; optimistic 62; schema-driven 216; unrealistic 243, 244, 247–9 experiential techniques 202, 209, 210, 213 experiments 108, 111, 163; behavioural 31–2, 116, 138, 139, 140, 142, 144, 145, 165, 167 explanations: alternative 117, 262, 263, 264–5, 278; biased 257 exposure 98, 101–2, 103, 104, 106, 130, 158; experiment viewed as a form of 165; imagery 159; interoceptive 105, 118; prevention 284; progressive 116; role in CB treatment 131; systematic 108; therapeutic value of 167; see also ERP externalising disorders 279, 280; see also ADHD; aggression extreme sports 85 exuberance 82 failure 3, 5, 7, 10, 11, 72, 89, 165, 207, 288 faintness 112, 113 Fairburn, C. G. 185 Falloon, I. R. H. 268 families 66, 67, 77, 242–74, 291, 299; intrusive 90; suicide runs in 51 family therapy 67, 177–8, 194–6, 266, 295 fantasies 220, 261; sexual 75 fasting 174 fatigue 7, 99, 150; chronic 163 FBI (Family Beliefs Inventory) 250 FCT (Focused Cognitive Therapy) 109, 118 fears 21, 26, 49, 91, 116, 118, 144, 162, 165–6; agoraphobic 97–8; behaviours that reduce 107; catastrophic 100, 101; children’s 282; confronting 107; contamination 133, 140; justifying 163; related to abandonment 225; separation 179; short-lived 280 feedback 15, 79, 87, 89, 111, 116, 117, 183, 216, 218; completing the loop 32; continuous 113; corrective 73; counteracting the loop 267; extensive 321 112; honest 19; insufficient 77; key 35; valuable 80 Feindler, E. L. 293 Fieve, R. 77 ‘fight and dwell’ style 138 fight-or-flight response 110 Fincham, F. D. 251 Finch, A. J. 277 Fishman, H. C. 255 Flannery-Schroeder, E. C. 283 flashcards 82–3, 108, 213, 217 Fleming, B, 251 Foa, E. B. 125–6, 131, 141, 284 fond memories 8 food 174, 182, 183, 185, 186; fat-free 188; feared, exposure to 178–9; quality of 187; quantity of 186–7 forgetting 31 FOS (Family-of-Origin Scale) 251 Foster, S. L. 268, 270 Franklin, Benjamin 84 Franklin, M. E. 131 free will 53 Freeston, M. H. 128, 129, 137, 138, 139, 142, 143, 144 Freud, Sigmund 196 friendships 289 Frost, R. O. 145 frustration 19, 56, 85, 153, 167, 247; inevitability of 86; low tolerance 225 GAD (generalised anxiety disorder) 150–72, 282, 296 Garland, A. 92 Garner, D. M. 177, 181, 192 Gelder, M. G. 98, 103 genetics 51, 71 gestalt 209 gestures 152, 224; suicidal 50, 55 Gitow, A. 284 global techniques 87 goals 11–12, 34, 65, 71, 73–87, 88, 191, 211, 278; central 288; conflicting 60; defined 107; failure to achieve 89; functional 33; long-term 89, 224; overarching 297; positive, achievable 91; setting 136; vague 10 Goebbels, Joseph 26 Goldfried, M. R. 85 Goldstein, A. J. 98 ‘goodness’ 139 Graae, F. 284 322 Index grandiosity 72, 76, 77, 191, 220 gratification 76 Greenberg, R. L. 102–3 grief 91 Grotevant, H.D. 251 groups 36–7, 92, 169, 289–90, 298, 299 Guerney, B. G. 269 Guidano, V. F. 188 guilt 17, 25, 128, 133, 137, 186 habit 162 habituation 127 Hackmann, A. 103 hallucinations 5, 58, 65–6 hallucinogens 76 HALT (Hungry, Angry, Lonely, and Tired) 55–6 happiness 10, 19, 90, 130, 166 hardships 88–9 harm 83, 250, 280; self 33, 49, 224 Harrison, J. 127 headaches 7, 23 heart attacks 106, 140 heart disease 3 heart rate 106, 110, 111, 114, 160, 281 helplessness 6, 88, 191, 225, 245, 246; perceived 14, 21; reducing 21–2 Henin, A. 283, 284 Herbel, B. 285 heredity 71 high-risk situations 84–5 Hirshfeld, D. R. 92 history 67, 91; psychiatric 87, 88 histrionic suiciders 57–8, 65 Hodgson, R. 126 Hoffart, A. 102 holidays 51, 76 homework 15, 16–18, 35–6, 87, 108, 113, 117, 157, 175, 285; compliance with 116, 126; difficulty with 215; discontinuing 86; many possible kinds 218; problems encountered with 137; reviewed 115; rewards and 279; selfexposure 103; typical assignment 134 hope 12 hopefulness 51 hopelessness 11, 15, 215, 238; BD and 72, 74, 76, 88, 91; suicidality and 49, 50, 52–4 passim, 56–62 passim, 65, 67, 68, 91–2; see also BHS hormonal functioning 185 hospitalisation 51, 52, 55, 60, 64, 178, 185, 294; disagreement with need for 67; partial 175; past, multiple 91 hostility 225, 247 hot and cold flushes 118–19 Howard, B. 284 humiliation 100 hurt 248 hyperactivity 151; see also ADHD hyperalertness 98 hypertension 3, 71 hyperventilation 97, 101, 105, 107, 108, 115; breathing incompatible with 114; panic induction through 112–13, 116 hypervigilance 100, 225 hypnosis 98 hypomania 72, 73, 74, 75, 77, 79, 80, 83; breathing control 85; overactive tendency 84; overconfidence 82 ideation: overvalued 126; suicidal 16, 49, 53, 57, 58, 59 identity 188, 191, 224 ignorance 88 illusions 163 imagery 29, 108, 159, 210, 211, 213, 261, 277; anxious 117; coping 117; fearful 113; guided 215, 217; pleasant 154, 156; spontaneous 115; techniques 214–15; training 289 images 7, 8, 12, 18, 20, 24, 109, 113; accessing 230; anxiety-provoking 159, 160, 161, 162; automatic 11; brief, threatening 115; catastrophic 159; distracting 156; dreadful 115; dysfunctional 23, 29; individual 165; positive 156, 261; real life 214; restructuring 107; unwanted 126 imaginal response systems 169 imagination 34 imipramine 97, 103, 298 impasses 34 impulses 126, 132, 207 impulsive behaviour 73, 74, 88, 89, 223, 225, 267, 293, 296, 297 impulsive behaviour control 52, 55, 65, 82–5 impulsive suiciders 57, 63, 67 inadequacy 18 inattention 296, 297 incompetence 27, 190, 207 Index inferences 216, 245; arbitrary 256 information-processing 87, 230–1, 275–6; errors 288; faulty 5, 258 infusions 97 inhibition 207–8, 280 inner-city children 296 insecurity 89 inspiration 33 integration model 177, 178 integrative models 268 intention-to-treat analyses 104 intentionality 251 intentions: negative 257; paradoxical 102 interactions 36, 67, 151, 157, 195, 196; couple and family 243–4, 247, 249, 250, 252–67 passim, 285; negative 247; social 87, 190, 292 interests 8 internalising disorders 279–80; see also anxiety; depression Internet 37 interoceptive conditioning model 98 interpersonal situations 36, 118, 177, 179, 180, 194, 292, 294; boundaries 225; control 79; focus 193–4; problems 169, 194, 203, 293; relations 216–17, 223, 296; techniques 212, 215 interpretations 25, 27, 107, 108, 114, 131, 179, 193; anxiety-provoking 162–3; dysfunctional 11; negative 162, 201 interrelationships 9 intervention 35, 100, 108, 110, 117, 145, 177; behavioural 21, 111, 268–70; child-focused 295; cognitive 32, 65, 111; core beliefs as targets for 165; exposure 158; family 266, 268, 295; multicomponent 281; planning 109; poor result from 8; prevention 290; providing coping skills 151; reflective 203; self-help 76; specific targets for 153; suicidality 53, 59–66 interviews 67, 252, 286 intimacy 225 intravenous administration 97 intrusions 126–7, 129, 134, 144; challenging 143; sexual 128, 139 inventories see BAI; BDI; FBI; ISRS; RBI; Young irritability 75, 76, 85, 88, 150; shifts from baseline mood to 224 isolation 7, 190, 207 323 ISRS (Inventory of Specific Relationship Standards) 249, 250, 251 Issues Checklist 255 Jacob, T. 251 Jacobson, N. S. 98, 248, 268 Jaffer, M. 284 Jamison, K. R. 77 jealousy 88 jet travel 74, 85 Kahn, D. A. 77 Kane, M. T. 282, 283 Kashani, J. H. 280 Kazdin, A. E. 293 Kendall, P. C. 277, 280, 282, 283, 284, 296 Kernberg, O. F. 224 ‘kindling effect’ 91 Kirk, J. 137 Klein, D. F. 97 Klosko, J. S. 105 Kozak, M. J. 125, 131, 141 labelling 18, 67, 144, 193, 255–8, 293 Ladouceur, R. 128, 145, 146 Lam, D. H. 92 laxative abuse 174, 176, 183–4, 185 Layden, M. A. 7, 224–5 lethargy 72 light-headedness 114, 119 Limb, K. 92 limited reparenting 215 Liotti, G. 188 listening 83, 84, 269; reflective 168 lithium 71, 90 Lochman, J. E. 293, 294 logbooks 83 loss 5, 54; major 55, 56; parental 51; tragic 7 love 207, 244, 250, 262; partner’s lack of 251 McCarthy, E. 92 MacDonald, J. 280 McFall, M. E. 126, 128, 130 McLean, P. D. 137, 143 McMaster Family Assessment Device 251 McMullin, R. E. 22 magnification 256, 257 Mahoney, M. J. 276 324 Index maladaptiveness 5, 14, 22, 24, 27, 232, 288; causal attributions 289; consequences 190; emotions 181; schemas 204–5, 209, 210, 214; thoughts 204, 217; see also EMS maladjustment 291 malevolence 88 malicious intent 250, 251 mania 74; early warning signs 77; see also hypomania mania management 87 manic episodes 72, 74, 80, 81, 84; early stages 82; warning signs 75 manipulative suicide attempts 54, 55, 65 Marchione, K. 102 March, J. S. 285 Margolin, G. 248, 268 Margraaf, J. 105, 111 marital problems 261, 291 Markman, H. J. 269 Marks, I. M. 98, 102, 110, 126 MAS (Marital Attitude Survey) 251 mastery 278, 279, 282 MDD major depressive disorder) 287, 289 meal planning 175, 178, 186–7 meanings 7, 24, 53, 195, 196; co-creation of 22; deeper 12, 13; distorted 179, 193; idiosyncratic 108, 113; implicit, higher-order 188; personal construction of 6 mechanical eating 186–7 medication: ADHD 298, 299; antipsychotic 58; anxiety 168; BD 71, 74, 88, 89, 90, 91; depression 4; eating disorders 174, 187; OCD 125; panic 104–5, 109; psychotropic 89–91; suicidal behaviour and 52, 55, 65 meditation 154, 156, 158 Meichenbaum, D. 267–8 Meissner, W. W. 224 memory 166, 204, 261; see also fond memories menstruation 173, 185 mental illness 3 mental pictures 14 metacognition 22–4 metaphors 8, 12 methylphenidate 298 Middleton, H. 103 Miller, L. S. 297 mind reading 80, 249, 257 minimisation 76, 256 Minuchin, S. 195, 255 misery 7, 34 mislabelling 256 mistakes 25, 28, 33, 208; repeating 76 mistrust 88, 207, 216, 219, 224, 225 MLH (Multimodal Life History) 210 modelling 73, 279, 296 moderation 84 monozygotic twins 51 mood 6, 10, 15, 17, 61, 91, 151, 225, 280; abnormalities 80; clinical disorders 287; depressed 20, 163, 166; downturns 13, 14; early warning signs of problematic shifts 74; elevated 76; erratic 76; good 75, 77; hypomania and 75; instability of 223; negative shift in 23; positive effects on 21; severe disturbances 81; upswings 14 Moorhead, S. 92 morality 139 Moras, K. 105 Morriss, R. 92 mortality 56 mothers: bad 29, 30, 31; good 30 motivation 61, 64, 175, 177, 186, 236; for change 176, 184, 224; selfish 251; unconscious 181 Mulle, K. 285 multidimensional models 175 multisystemic treatment 296 muscle relaxation 85, 105, 155–8 myocardial infection 56 narcissistic personality disorder 219, 220, 225 nausea 119 Needleman, L. 177 negative framing 258–9, 264 Nelson, W. M. 277 nervousness 57, 58 neurochemical disorder 97 neurological disability 67 ‘New Year’s resolution’ style 191 New Zealand 280 Newman, C. F. 34, 118 nicotine 76 Nietzel, M. T. 297 non-compliance 17–18, 35–6, 224 non-directive therapy 168 Norton, G. R. 119 Index nutrition 10, 184–7 OAD (overanxious disorder) 282, 283, 287 obedience 250 object relations 209 observation: behavioural 254–5, 283; clinical 56 obsessions 54; sexual 143; see also OCD obstacles 255 OCCWG (Obsessive-Compulsive Cognitions Working Group) 128 OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder) 9, 125–49, 282, 284–5, 287 ODD (oppositional defiant disorder) 296 Orvaschel, H. 280 Ost, J.-G. 103, 104 O’Sullivan, G. 126 other-directedness 207 outcomes see treatment outcomes overbreathing 101, 102, 112, 113 overconfidence 82 overdoses 52 overgeneralisation 256 overidealisation 223 overprediction 100, 129 overprotectivenesss 179 overvigilance 207–8 Oxford Cognitive Therapy Package 107, 108 Ozarow, B. J. 125, 284 pain 19, 33, 206; acute 55; cessation of 34; chronic 55, 220; emotional 225; intractable 58; stomach 7; paired words 113 Palmer, A. G. 92 palpitations 112, 113, 114, 118 panic disorder 9, 97–124, 132, 140, 282, 285–6; breathing control 85; central feature of treatment 144; feared 217 Panichelli-Mindell, S. 283 paradoxical intention 102 paranoia 225 parent-training approaches 298 Parental Authority Questionnaire 252 passions 8 passive-aggressive behaviour 88 patience 73, 83, 85 325 Penn State therapy study 157, 162, 165, 169 perception 53, 188, 204, 213, 259, 266; biased 28; faulty 267; self 191, 251, 288 perfectionism 128, 130, 135, 145, 156, 187, 191, 208, 215, 250; challenging 142 performance 166, 192, 208, 288; impaired 207; inconsistent 296 Perlmutter, B. E. 251 Perry, A. 92 personalisation 256, 262 personality 251 personality disorders 126; schemafocused therapy for 201–22; see also BPD Persons, J. 7 pessimism 208 pharmacotherapy 4, 37, 97, 106, 119, 178; compliance with 89, 90; longterm 91 phobias 159, 282 physical complications 184 physiological factors 10, 73, 97, 110, 151, 152, 155; arousal 98, 115, 281, 293; disturbances 105 Piacenti, J. 284 Piaget, J. 232–3 pie-chart technique 137–8 pills 49, 55 placebo therapy 168 pleasure 20, 21, 30, 193, 208 PMR (progressive muscle relaxation) 155–6, 159 point-counterpoint 28 positives 264 Possible Reasons for Not Doing Homework Assignments Sheet 35–6 precautions 63 predictability 74 predictions 139, 141, 162; accurate 163, 166; catastrophic 106, 116; disconfirming 107, 116; fearful 100; implicit 190; incorrect 32; negative 107, 164, 165, 166, 169; testing 263–4; see also overprediction predisposition 7, 35, 175 premonitions 139 Pretzer, J. L. 250 Printz, D. J. 77 priorities 107 326 Index problem-solving 12, 13, 87, 89, 98, 107, 236, 268; advanced 72; application of techniques 117; assessing 251; collaborative and constructive 250; effective 5, 49, 80, 81, 294; exemplifying 293; exploring options in terms of 34; helpful 166; improving skills 255; ‘middle-ground’ approach 82; modelling of strategies 296–7; poor strategies 54; practical 32–3; principles/practices 73, 81; social 59, 277, 292; thought of as a sequence 278; training 270 procrastination 7 protection 12, 214 provocation procedures 105 psychiatric problems 5, 91; comordic disorders 9; inpatient children 294 psychoactive substances 73 psychoanalysis 196, 205, 216, 243 psychodynamic therapy 105, 179, 243, 286 psychological treatments 97–8, 105, 106 psychology 202; social 131–2 psychopathology 182, 203, 204, 280, 285 psychosocial treatment 71, 73, 105, 125–49; failure to respond to 178; periodic 91 psychotic features 231 psychotic suiciders 57, 58, 65, 66 PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) 282, 286–7 public places 98 punishment 289 Punitive Parent mode 219 Purdon, C. 129 quality of life 76, 91, 107, 117 Rachman, S. 110, 125, 126, 124, 128 rage 189, 225, 245; pent-up 219 RAM (Relationship Attribution Measure) 251 random killing 128 Rankin, L. A. 249, 251 rape 238 Rapee, R. 284 rapport 59, 60 RAR (reasonable adaptive response) 25, 26, 28, 29 rational-emotional therapy 27, 102; see also REBT rational suiciders 57, 58 RBI (Relationship Belief Inventory) 249 reactions 34, 67, 111, 113, 115, 116, 152, 204, 231; antitherapeutical 224; child’s body 277; exaggerated 258; impulsive 267; physiological 159; rage 225 reading impairment 16 reality 73, 77–80, 163, 164; construction of 6 reappraisal 116, 276 reasonableness 247 reasoning 77, 117, 128, 178; dichotomous 189–90; emotional 21, 137; faulty 129 reassurance 225 reattribution 108, 191 REBT (Rational-Emotive Behaviour Therapy) 243 recklessness 73, 82–5, 225; manic 81 reflective delay 73 refocusing 109, 114, 115, 117, 157, 166 reframing 92, 187–8, 262–3, 264 regression 215 regret 86 reinforcement 282; contingent 277; self 288, 289 rejection 25, 206–7, 215; peer 291; social 190 relapse 4, 104, 125; prevention 36, 108, 117, 144, 202, 220, 289, 291; protection against 12; reframing 187–8 Relationship Attribution Questionnaire 251 relationships 9–10, 19, 226; assessment 249–55; beliefs about 245–6; collaborative 202, 203; difficulties in 80; functional 179; historical 194; integral 12; interpersonal 216–17, 223, 296; primary attachment 203; sexual, illicit 86 see also couples: families relaxation 22, 73, 75, 102, 108, 109, 117, 151, 165, 285, 286, 294; applied 103, 104, 154, 158, 168; Jacobsian 85; methods 154–61; progressive 277 relief 10–11, 86 remission 90 reparative corrections 76 repetition 26, 156, 213 representation 205; mental 29; verbal 115 ‘rescue’ 65 resentment 248 Index resistance 28, 79, 176, 203, 225, 248 respect 90 responsibility 127, 133–4, 139–40, 248, 251; disowning 260–1; inflated 128, 129, 135, 137–8, 145 restlessness 151 resuscitation 58 ‘rewarding non-punishment’ 133 rewards 166, 278–9, 289, 292; self 293 Rheume, J. 128, 145 RIA (relaxation-induced anxiety) 156, 157 rights 193, 225; equal 248; suicidal patients 52–3, 58 rigidity 193, 203–4; cognitive 59 risk 84–5, 107, 129, 131; avoidance of 190; mood abnormalities 80; suicidal 50, 51, 53–5, 56, 57, 64, 67, 82 Robin, A. L. 268, 270 role play 28, 73, 162, 209, 261, 277, 278; Devil’s advocacy 78–9; rationalemotional 27 Ross, R. 77 Roth, W. T. 111 Rubin, K. H. 280 ruination 250 Rush, A. J. 245 Sachs, G. S. 77, 92 sacrifices 86 SAD (separation anxiety disorder) 282, 283, 287 sadness 164 safety behaviours 7, 49, 54, 100, 106–8 passim, 111, 114; dropping 116, 117 Safran, J. D. 5–6 Salas-Auvert, J. A. 113 Salkovskis, P. M. 103, 106, 125, 126–7, 137, 140, 145 Sanders, M. R. 268 satisfaction 244 scanning 151 SCD (self-control desensitisation) 151, 159–61, 165, 166 schema compensation 206 schemas 66, 175, 188, 216, 226, 227–30; activated by anxiety 236; family 190; interpersonal 193, 194; maladaptive 204–5, 209, 210, 214 schizophrenia 5 Schlesinger, S. E. 266, 267 Scott, J. 92 327 screaming 245, 246 Segal, Z. V. 5–6, 204 selective abstraction 256 self: distorted view of 212; negative interpretations of 201; overwhelmed 191; perfectible 191; underdeveloped sense of 225; unworthy 191 self-attributions 190 self-compassion 6 self-concept 191–2 self-consciousness 59 self-control 52, 289, 293; see also SCD self-damage 49, 67, 223 self-defence 139 self-destruction 49, 178 self-doubt 178 self-efficacy 6, 22, 78, 213 self-esteem 191, 292; behaviours that increase 107; fragile 79–80; improving 191–2; very low 225 self-estimation 178 self-evaluation 288, 289, 293, 296 self-focus 100, 280 self-fulfilling prophecy 100 self-hatred 219 self-help 14, 36–7, 74, 76, 92 self-image 223 self-instruction 83–4, 89, 102, 267 self-monitoring 73, 86, 89, 151, 178, 179, 185–6, 289; early cue detection and 152–3; exaggerated 193; problematic absence of 82 self-mutilating behaviour 223, 224 self-programmes 117 self-regulation 110, 299 self-reliance 117 self-reports 53, 54, 249–52, 254, 283, 285 self-restraint 73 Self Soother mode 219, 220 self-statements 86, 281, 293 self-talk 278, 282, 285 self-worth 142, 191; ‘balance sheet’ concept of 192; vague assumptions about 192 sensations 193; panicogenic 108, 112, 115; somatic 105; see also bodily sensations sensory channel 230 sentiment 253 separation-individuation 179 serious affective disorders 89 sexual abuse 30, 88, 231, 286 328 Index SFT (schema-focused therapy) 201–22 Shafran, R. 128 shaking 118 shame 29, 76, 128, 133, 137, 207 Shaw, B. F. 245 Shure, M. B. 293 side-effects 71, 90, 91 sights 156, 160 significant others 51, 58, 60; reliable 63; use of, in therapy 66–7 Silva, P. de 110, 126, 127 Silverman, W. K. 282, 283 simplicity 191 sleep 73, 74, 75, 154, 163; disturbances 22, 150, 298 slowing down 87, 89 smell 8, 156, 160 snacks 184, 186 social contact 7 social environments 191 social learning model 242, 275 social skills 12, 288, 289, 299 socialisation 13–14, 84, 108, 235 sociocultural effects 6 Socratic questioning 19, 24, 29–30, 68, 77–8, 89, 107, 236, 252; guided discovery as established through 132; persistent 111 Sokol, L. 102–3 somatic sensations 105 sounds 156, 160 Southam-Gerow, M. A. 283 spacing eating 186 Spanier, G. B. 254 Special Self mode 219 specific techniques 19–20 Spivack, G. 293 spontaneity 82, 87, 207 SSI (Scale of Suicidal Ideation) 54 stability 74 standards 249–50, 252, 288 Stanley, S. 269 Stark, K. D. 291 startle response 151 starvation 175, 176, 182; physical complications associated with 184 Steketee, G. 125, 145, 284 stepped-care model 177, 178 STEP-BD project 92 stigma 3 stimulants 76 stimulation 57, 65, 75, 84, 220, 225 stimuli 55, 258, 285; conditioned 98; discriminative 154; external 98, 105; feared 281; internal triggering 99; interoceptive 105; phobic 159 stimulus control 84, 100, 151, 153–4 ‘Stop and Think’ treatment 296 Straus, M. A. 251 stream of consciousness 237 stress 7, 10, 55, 71–2, 73, 80–1, 278; coping with 8, 107; hyperventilation induced by 101; identification and modification of stressors 117; see also PTSD strife 75 Stuart, R. B. 264, 268 Subjugation schema 218, 219 substance abuse 7, 9, 10, 55, 73, 84, 220, 223, 225, 280, 288 success 18, 19, 33 suffering 30, 33 suffocation 113 suicidality 16, 49–70, 78, 82, 89, 224, 290; addressing 33–4; hopelessness and 49, 50, 52–4 passim, 56–62 passim, 65, 67, 68, 91–2 superiority 207, 219 support mechanisms 10, 67 suppression 129, 139 suspicion 225 sweating 119 Swinson, R. P. 119 symmetry/exactness compulsions 130 sympathetic nervous system 83, 155 symptoms: ADHD 296, 297, 298, 299; anxiety/panic 98–103 passim, 107–15 passim, 118, 119, 280, 281; BD 71, 74, 77, 84, 86, 92; depressive 4, 6, 9, 10–11, 13, 15, 72, 291; eating disorders 175–9 passim, 182, 184, 185–6, 190, 191, 194, 195; GAD 150–1; hyperventilation 113; neurophysiological 111; OCD 125–6, 136–7; physiological arousal 98; psychotic 65, 66; suicidality 67; PTSD 286; starvation 176, 182 TAF (thought-action fusion) 128, 138–9 target problems 11–12 Tarrier, N. 92 Taylor, C. B. 111 teenagers 250 Telch, M. J. 105 Index temper tantrums 64 Temple University 282 Tennenbaum, D. 251 tension 86, 156, 160, 277; motor 151; muscle 150, 152, 155, 158, 166 Thase, M. E. 92 therapeutic alliance see therapeutic relationship therapeutic relationship 11, 88, 131, 176, 212, 235; boundaries of 215; distortions in 20; importance of 176; nature of 87; nurturing 34–5; quality of 87, 111; ruptures in 167; schemas triggered within 216; strong 176 thinness 178 Thordarson, D. S. 128 ‘thought bubbles’ 278 thoughts/thinking 6, 16, 34, 106, 109, 110, 115, 162; active restructuring of 59; adaptive 10, 28; alternative 164; biased 72, 77, 81–2; blasphemous 140; catastrophic 111, 190, 204; control over 129, 139–40; depressogenic 289, 290; dichotomous 187, 256; distorted 5, 205, 263; distracting 156; dysfunctional 5, 23, 53, 188, 189, 257, 264; erratic 76; extreme or all-ornothing 224; faulty 243, 247, 277; hyper-positive 77–80; improved process 107; individual 165; intrusive 126, 127, 131, 133, 134, 138, 140, 143; irrational 243; maladaptive 204, 217; mindreading 249; monitored 235; negative 243; non-anxiety-provoking 165; obsessive 144; overimportance of 128–9, 135, 138–9, 145; perfectionist 187; pessimistic 73; powerful impediments to 28; previously avoided 211; problematic 77; reality testing of 73; schema-driven 216; suicidal 49, 54, 55, 57, 59, 60, 62; threatening 127; unfocused 86; unwanted 126, 129, 134, 139; worrisome 154, 156, 166; see also ATs; TAF threat 56, 106, 127, 225; neutralised 133; over- estimation of 128, 129, 140–1, 144; tolerance 85, 184, 225 Touliatos, J. 251 Tran, G. Q. 118 transference 179 trauma 76, 88, 231, 275; early childhood 245; see also PTSD 329 treatment outcomes depression 8; GAD 156, 157, 167–9; OCD 125, 126, 140, 144–6; PD 103, 105 trembling 118, 119 tricyclics 52 triggers 36, 67, 117, 226, 227, 231, 259; anxiety 152, 153, 158, 159, 161; OCD 133; panic attacks 99, 100, 110, 115; schema 206, 209–11 passim, 213, 216, 217 trust 7, 88, 235; self 191 truth 12, 26, 116, 276 tunnel vision 256 turbulence 8 twins 51 ulterior motives 257 uncertainty 224; intolerance of 128, 129–30, 141–2 uncontrollable behaviours 293 undercontrolled behaviour 72 understanding 6, 11, 49, 233, 236; limited 50; self 8 unfairness 250 unhappiness 10 United Kingdom 3, 118 United States: BD 71; depression 3, 4; OCD 128; panic attacks 118 University of British Columbia 145 unloveability 225, 226, 229 unpredictability 84 unreality 112 Unrelenting Standards schema 215, 219 urges 133, 182 urination 151 validity and reliability 193 van den Hout, M. 104 van Oppen, P. 129, 137, 140, 143, 144, 145 verbal channel 231 ‘vicious circle’ model 99 vigilance 82, 151; see also hypervigilance; overvigilance Vincent, J. T. 252 visual impairment 16 visualisation 28–9, 161, 215 Vitousek, K. B. 191 voices 58, 66 vomiting 176, 177, 185, 187; involuntary 196; preventing 179; self-induced 174, 180, 183 330 Index vulnerability 6, 54–5, 187, 207, 245; perceived 246; suicidal patients 55–6 Vulnerable Child mode 219 Warman, M. 283 weakness 3, 67, 88 Weiss, R. L. 252 well-being 22 Wells, A. 108 Westbrook, D. 125 Westling, B. E. 103, 104 Whitaker, A. 284 Whittal, M. L. 137, 143 Wilhelm, S. 145 ‘wise sayings’ 82–3 withdrawal 7, 182, 225, 262, 263, 280; medication 125 Wollersheim, J. P. 126, 128, 130 work schedules 74 workaholism 220 World Wide Web 37 worry 150–72, 280 Wright, F. D. 102–3 YBOCS (Yale-Brown ObsessiveCompulsive Scale) 145, 146 Young, J. E. 202, 203, 204, 206, 208, 220, 228; Inventories 210 ‘zeitgebers’ 74