Flow Diversion for Treatment of Partially Thrombosed Aneurysms: A Multicenter Cohort

реклама

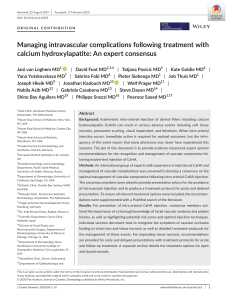

Original Article Flow Diversion for Treatment of Partially Thrombosed Aneurysms: A Multicenter Cohort Paul M. Foreman1,5, Mohamed M. Salem2, Christoph J. Griessenauer1,6, Adam A. Dmytriw7, Carmen Parra-Farinas8, Patrick Nicholson7, Nicola Limbucci9, Anna Luisa Kühn3, Ajit S. Puri4, Leonardo Renieri9, Sergio Nappini9, Kimberly P. Kicielinski2, Alejandro Bugarini1, Vitor Mendes Pereira7, Thomas R. Marotta8, Clemens M. Schirmer1, Christopher S. Ogilvy2, Ajith J. Thomas2 BACKGROUND: Partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms (PTIA) represent a unique subset of intracranial aneurysms with an ill-defined natural history, posing challenges to standard management strategies. This study aims to assess the efficacy of flow diversion in the treatment of this pathology. - METHODS: A retrospective review of patients with flowdiverted PTIA at 6 cerebrovascular centers was performed. Clinical and radiographic data were collected from the medical records, with the primary outcome of aneurysmal occlusion and secondary outcomes of clinical status and complications. - RESULTS: Fifty patients with 51 PTIA treated with flow diversion were included. Median age was 56.5 years. Thirty-three (64.7%) aneurysms were saccular and 16 (31.4%) were fusiform/dolichoectatic. The most common location was the internal carotid artery (54.9%) followed by the vertebral and basilar arteries (17.7% and 17.7%, respectively). Last imaging follow-up was performed at a median of 25.1 (interquartile range, 12.8e43) months. Complete occlusion at last radiographic follow-up was achieved in 37 (77.1%) aneurysms. Pretreatment aneurysm thrombosis of >50% was associated with a significantly lower rate of complete aneurysm occlusion (58.8 vs. 87.1%, P [ 0.026) with a trend toward better functional outcome (modified Rankin scale <2) at last follow-up in patients with <50% pretreatment aneurysm thrombosis (96.8 vs. 82.4; P [ 0.08). Ischemic complications occurred in 5 (9.8%) patients, producing symptoms in 4 (7.8%) and resultant mortality in 2 (4.2%) patients. CONCLUSIONS: Flow diversion treatment of PTIA has adequate efficacy along with a reasonable safety profile. Aneurysms harboring large amounts of pretreatment thrombus were associated with lower rates of complete occlusion. - - Key words Aneurysm - Complication - Flow diverter - Occlusion - Pipeline - Thrombosed aneurysm - Thrombus - Abbreviations and Acronyms CN: Cranial nerve CT: Computed tomography CTA: Computed tomography angiography DSA: Digital subtraction angiography IQR: Interquartile range MRA: Magnetic resonance angiography MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging mRS: Modified Rankin scale PTIA: Partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysm e164 www.SCIENCEDIRECT.com INTRODUCTION P artially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms (PTIA) are a rare and diverse subset of intracranial aneurysm with a distinct, but ill-defined, natural history. These aneurysms are often large or giant in size, and although they can present with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, a more insidious presentation due to mass effect is more common.1 Their size coupled with the presence of organized thrombus makes surgical From the 1Department of Neurosurgery and Neuroscience Institute, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Pennsylvania; 2Division of Neurosurgery, and 3Division of Neuroradiology, Department of Radiology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Teaching Hospital, Boston; 4Division of Neuroimaging and Intervention, Department of Radiology, University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, Massachusetts; 5Orlando Health, Neuroscience and Rehabilitation Institute, Orlando, Florida, USA; 6Research Institute of Neurointervention, Paracelsus Medical University, Salzburg, Austria; 7Department of Medical Imaging, Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; 8Department of Interventional Neuroradiology, St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; and 9 Department of Interventional Neuroradiology, University of Florence, Florence, Italy To whom correspondence should be addressed: Paul M. Foreman, M.D. [E-mail: [email protected]] Citation: World Neurosurg. (2020) 135:e164-e173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.11.084 Journal homepage: www.journals.elsevier.com/world-neurosurgery Available online: www.sciencedirect.com 1878-8750/$ - see front matter ª 2019 Published by Elsevier Inc. WORLD NEUROSURGERY, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.11.084 ORIGINAL ARTICLE PAUL M. FOREMAN ET AL. obliteration challenging and can require advanced techniques complicated by mortality rates of 6%2 and unfavorable outcomes in 18%.3 Standard endovascular embolization with detachable coils has also yielded unsatisfactory long-term results due to continued aneurysm growth and recanalization rates as high as 78%.4-6 Food and Drug Administration approval of the Pipeline Embolization Device in 2011 added flow diverting stents to the interventionalist’s armamentarium. Placement of flow diverting stents within the parent artery obviates the need to enter or manipulate the PTIA, potentially reducing complication rates. The durability of aneurysm occlusion after parent artery reconstruction also has the potential to overcome shortcomings of traditional endovascular techniques while avoiding parent artery occlusion. Despite these conceivable advantages, there is concern that evolving thrombosis can lead to destabilization of the aneurysm wall and predispose to rupture7,8; however, the effect of preexisting thrombus on this risk is not known. In addition, the impact of the chemical milieu of pre-existing intra-aneurysmal thrombus on occlusion rates is also unknown. We present an international multicenter cohort of PTIA treated with flow diverting stents in an effort to further define the safety and efficacy of the procedure for these aneurysms. FLOW DIVERSION FOR THROMBOSED ANEURYSMS persistent filling of aneurysm; stable, no change in aneurysm filling; larger, increased filling of aneurysm. Secondary outcomes included clinical status at last follow-up and thromboembolic and hemorrhagic neurologic complication rates. The study was approved at participating centers by their respective internal review boards. Patient consent was not required for this retrospective chart review project. Statistical Analysis Continuous variables are presented as mean standard deviation or median (interquartile range [IQR]), as appropriate according to the data distribution, whereas categorical variables are reported as proportions. Aneurysms were categorized into 2 groups according to their pretreatment thrombosis status (50% vs. <50% thrombosis). In each group, categorical variables were compared using the c2 test and continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed to identify predictors of incomplete occlusion based on potential predictors on univariate screening. Statistical significance was set to a P value of less than 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the STATA 15 software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). RESULTS METHODS A retrospective review of consecutive patients with PTIA treated with endovascular placement of a flow diverting stent at 5 international cerebrovascular centers from 2009 to 2018 was performed. The inclusion criterion was imaging evidence of a PTIA that was treated with endovascular placement of a flow diverting stent. The diagnosis of a PTIA was made when the diameter of an aneurysm of cross-sectional computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was greater than the diameter of the perfused aneurysm on computed tomography angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), or digital subtraction angiography (DSA). In addition, aneurysms were grouped into 2 categories (50% or <50%) based on the percentage of aneurysm thrombosis on pretreatment axial MRI/MRA or CTA. A dichotomous category was used to improve reliability across centers and imaging modalities and allow for an adequate number of aneurysms in each group for statistical comparison. Both ruptured and unruptured aneurysms were included. All aneurysm morphologies and locations were eligible for inclusion. Data collected included patient age, sex, past medical history, history of subarachnoid hemorrhage from index aneurysm, cranial nerve (CN) dysfunction caused by index aneurysm, functional status at presentation as measured by the modified Rankin scale (mRS), aneurysm characteristics, antiplatelet regimen, procedural details, complications, radiographic and clinical outcome, and final disposition (i.e., home, skilled nursing facility). Data were collected through review of the electronic medical record at each center. Data collectors were not blinded to the outcome characteristics. The primary outcome was aneurysm occlusion at last follow-up as determined by contrast filling of index aneurysm on CTA, MRA, or DSA. Occlusion status was defined as follows: complete occlusion, no filling of aneurysm; incomplete occlusion, reduced but WORLD NEUROSURGERY 135: e164-e173, MARCH 2020 Patient Characteristics Fifty patients with 51 PTIA treated with placement of flow diverting devices were included. Median age was 56.5 (IQR, 46e67) years and 60% of patients were female. Seventeen (34%) patients were current tobacco smokers and 7 (14%) were past smokers. The most frequent comorbidities included hypertension (56%), hyperlipidemia (28%), and diabetes (22%). Pretreatment mRS was 0 in 44% and 1e2 in 42% (Table 1). Aneurysm Characteristics Of the 51 PTIA, 33 (64.7%) were saccular in morphology, 16 (31.4%) were fusiform/dolichoectatic, and the remaining 2 (3.9%) were complex, multilobulated aneurysms unable to be classified as saccular or fusiform/dolichoectatic. Twenty-eight (54.9%) aneurysms affected the internal carotid artery, 9 (17.7%) the vertebral artery, 9 (17.7%) the basilar artery, 2 (3.9%) the middle cerebral artery, 2 (3.9%) the anterior cerebral artery, and 1 (2%) the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. The majority of aneurysms were side-wall (80.4%), with 10 bifurcation aneurysms in the cohort (19.6%). Eighteen (35.3%) aneurysms were more than 50% thrombosed before treatment. Forty-two (82.4%) aneurysms were unruptured at presentation and 26 (51%) produced CN dysfunction. Seven (13.7%) aneurysms had been previously treated with endovascular methods. The median size of the maximum dimension of contrast filling of the aneurysm on MRA, CTA, or DSA was 13 (IQR, 8.5e17) mm. The median size of the maximum dimension on an axial MRI or CT, including the thrombosed portion of the aneurysm, was 17 (IQR, 12e24.8) mm (Table 1). Procedural Details The Pipeline Embolization Device was used to treat 40 (78.4%) aneurysms, a SILK device in 4 (7.8%), an LVIS device in 3 (5.9%), an eCLIP device in 2 (3.9%), a combination of a SILK device and a www.journals.elsevier.com/world-neurosurgery e165 ORIGINAL ARTICLE PAUL M. FOREMAN ET AL. FLOW DIVERSION FOR THROMBOSED ANEURYSMS Table 1. Continued Table 1. Baseline Descriptive Statistics n [ 50 Treated Aneurysms Baseline Characteristics Male 20 (40%) Location Female 30 (60%) ICA 28 (54.9%) 56.5 (46e67) VA 9 (17.7%) BA 9 (17.7%) 39 (78%) MCA 2 (3.9%) Asian 5 (10%) ACA 2 (3.9%) African American 2 (4%) Number of Patients Bifurcation Sex Age (years), median (IQR) Race Caucasian PICA Hispanic 2 (4%) Pretreatment thrombosis 50% Unknown 2 (4%) Presentation Multiple intracranial aneurysms Family history of aneurysms 18 (36%) 2 (4%) Smoking history 42 (82.4%) 6 (11.8%) Ruptured (>2 weeks) 3 (5.9%) 26 (51%) 3 (5.9%) 26 (52%) Past smokers 7 (14%) Ischemia due to aneurysm Current smokers 17 (34%) Previous treatment Endovascular treatment 22 (44%) 1e2 21 (42%) Repeat flow diversion 8 (16%) Coiling 13e15 2 (4%) Comorbidities Hypertension 28 (56%) Hyperlipidemia 14 (28%) Diabetes 11 (22%) Coronary artery disease 6 (12%) Prior aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage 8 (16%) Prior stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) 8 (16%) Congestive heart failure 2 (4%) Peripheral vascular disease 4 (8%) Treated Aneurysms Baseline Characteristics n [ 51 Morphology Saccular 33 (64.7%) Fusiform/dolichoectatic 16 (31.4%) Other (multilobulated) 2 (3.9%) Sidewall versus bifurcation aneurysms Sidewall 41 (80.4%) Continues e166 www.SCIENCEDIRECT.com 6 (11.8%) 1 (2%) Filling size (greatest dimension of contrast filling) (mm)* 13 (8.5 e17) Axial size (greatest diameter on axial MRI or CT including thrombosed portion) (mm)* 17 (12 e24.8) 48 (96%) 3e5 7 (13.7%) Retreatment 0 Initial GCS 1 (2%) 18 (35.3%) Ruptured (acute) Never smokers 3e5 10 (19.6%) Unruptured Cranial nerve dysfunction Pretreatment mRS n [ 51 ACA, anterior cerebral artery; BA, basilar artery; CT, computed tomography; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; ICA, internal carotid artery; IQR, interquartile range; MCA, middle cerebral artery; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mRS, modified Rankin scale; PICA, posterior inferior cerebellar artery; VA, vertebral artery. *Measurements: median (IQR). Leo Plus stent in 1 (2%), and a DERIVO device in 1 (2%). Thirtynine (76.5%) procedures used a single flow diverter and 11 (21.6%) used 2 flow diverters. Pretreatment antiplatelet regimens included aspirin and clopidogrel in 48 (94.1%) cases and aspirin and ticagrelor in 3 (5.9%) cases (Table 2). Adjunctive coiling was performed in 16 (31.4%) cases, with complete neck coverage obtained in 88.2% of the cases (in 60% of bifurcation aneurysms). Ischemic neurologic complications occurred in 5 (9.8%) patients and produced symptoms in 4 (7.8%) with 2 mortalities. Transient hemorrhagic neurologic complications occurred in 1 patient. The median length of hospital stay was 4 days (Table 2). Radiographic and Clinical Outcomes Last imaging follow-up was performed at a median of 25.1 (IQR, 12.8e43) months. Forty-eight of 51 aneurysms had radiographic follow-up. Last follow-up imaging modality included DSA in 18 (37.5%), MRA in 26 (54.2%), and CTA in 4 (8.3%). The primary WORLD NEUROSURGERY, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.11.084 ORIGINAL ARTICLE PAUL M. FOREMAN ET AL. FLOW DIVERSION FOR THROMBOSED ANEURYSMS Table 2. Continued Table 2. Procedural and Outcomes Details Procedures Details n [ 51 Larger Flow diverters PED 40 (78.4%) SILK 4 (7.8%) LVIS 4 (7.8%) eCLIPS 1 (2%) SILK þ Leo Plus 1 (2%) DERIVO 1 (2%) Number of flow diverters placed 1 39 (76.5%) 2 11 (21.6%) 3 1 (2%) Flow diverters measurements Length (mm), median (IQR) Diameter (mm), median (IQR) Platelet function tests n [ 48* Aneurysm Imaging Follow-Up 21 (18e30) Last radiographic follow-up elapsed time (months), median (IQR) DSA 18 (37.5%) MRA 26 (54.2%) CTA 4 (8.3%) Occlusion status Completely occluded 37 (77.1%) Incompletely occluded 9 (18.8%) No change 1 (2.1%) Larger 1 (2.1%) Clinical Follow-Up n ¼ 19 Time to last follow-up (months), median (IQR) 19 (100%) Clopidogrel responders 16 (84.2%) Pretreatment antiplatelet medication Aspirin 325 mg þ clopidogrel 75 mg 48 (94.1%) Aspirin 81 mg þ ticagrelor 180 mg 3 (5.9%) 25.1 (12.8e43) Follow-up modality 4.2 (3.7e4.9) Aspirin responders 3 (6.3%) Last imaging follow-up n [ 48* 24.3 (11.7e43.3) mRS at last follow-up 0 33 (68.8%) 1e2 10 (20.8%) 3e5 3 (6.2%) 6 2 (4.2%) Pretreatment anticoagulation 8 (15.7%) Post-treatment anticoagulation 24 (47.1%) Improved 15 (31.9%) Adjunct coiling 16 (31.4%) No change 28 (58.3%) Balloon angioplasty 12 (23.5%) Post-treatment ischemic complications Symptomatic 5 (9.8%) mRS change (pretreatment to last follow-up) Worse Cranial nerve dysfunction 5 (10.4%) n ¼ 27 4 (7.8%) Resolved 8 (29.6%) Post-treatment hemorrhagic complications 1 (2%) Improved 5 (18.5%) Hospital length of stay (days), median (IQR) 4 (1e7) No change 11 (40.7%) Aneurysm Imaging Follow-Up n [ 48* First imaging follow-up First radiographic follow-up elapsed time (months), median (IQR) Worse Final disposition 3.8 (2.2e6.7) Follow-up modality DSA 21 (43.7%) MRA 27 (56.3%) Occlusion status Completely occluded 22 (45.8%) Incompletely occluded 18 (37.5%) No change 5 (10.4%) Continues WORLD NEUROSURGERY 135: e164-e173, MARCH 2020 3 (11.1%) n ¼ 48 Home 44 (91.7%) Rehab 1 (2.1%) Nursing home 1 (2.1%) Dead 2 (4.2%) CTA, computed tomography angiography; DSA, digital subtracted angiography; IQR, interquartile range; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; mRS, modified Rankin scale; PED, Pipeline Embolization Device. *Missing data for 2 patients. outcome of complete occlusion at last radiographic follow-up was achieved in 37 (77.1%) and incomplete occlusion in 9 (18.8%); 1 aneurysm was stable and 1 aneurysm increased in size. Six (11.8%) www.journals.elsevier.com/world-neurosurgery e167 ORIGINAL ARTICLE PAUL M. FOREMAN ET AL. FLOW DIVERSION FOR THROMBOSED ANEURYSMS Figure 1. A 69-year-old woman with a partially thrombosed right ICA aneurysm. (A) Pretreatment CTA. (B) Pretreatment DSA. (C) Follow-up DSA at 6 months demonstrates continued aneurysm filling. (D) Follow-up CTA at 20 months demonstrates continued aneurysm filling. (E) Follow-up aneurysms were retreated with flow diverters after their initial treatment with a flow diverter, whereas 1 aneurysm (2%) was coiled (Figures 1 and 2; Table 2). When univariate analysis was used to compare the group of patients with complete aneurysm occlusion at last follow-up with those without complete aneurysm occlusion, the complete occlusion group was significantly younger (median, 55 vs. 70 years, P ¼ 0.015), less likely to have multiple aneurysms (29.7% vs. 72.7%, P ¼ 0.01), and more likely to be current smokers (40.5% vs. 9.1%, P ¼ 0.008). There was also a trend toward higher rates of adjunctive coiling in patients with complete aneurysm occlusion (21.6% vs. 9.1%, P ¼ 0.09). Similarly, procedural complete neck coverage was obtained in 72.7% of the nonoccluded versus 91.9% in the occluded cohort (P ¼ 0.09) (Table 3). Last clinical follow-up was performed at a median of 24.3 (11.7e 43.3) months. Forty-eight of 50 patients had clinical follow-up. Secondary outcomes included clinical status (functional outcome, CN outcome, and disposition) and complication rates at last follow-up. Functional status as measured by the mRS, as compared with pretreatment, improved in 15 (31.9%), remained e168 www.SCIENCEDIRECT.com CTA at 32 months demonstrates continued aneurysm filling. CTA, computed tomography angiography; DSA, digital subtracted angiography; ICA, internal carotid artery. stable in 28 (58.3%), and worsened in 5 (10.4%). Of the 27 aneurysms causing pretreatment CN dysfunction, 8 (29.6%) resolved, 5 (18.5%) improved, 11 (40.7%) were stable, and 3 (11.1%) worsened. Forty-four (91.7%) patients had a final disposition of their own home, 1 to a rehabilitation center, 1 to a nursing home, and 2 (4.2%) died from ischemic complications (1 immediate, 1 delayed) (Table 2). Comparison of Aneurysms Based on Percentage of Pretreatment Thrombosis Pretreatment aneurysm thrombosis of 50% was found in 18 (35.3%) of aneurysms. Of these 18 aneurysms, 12 (66.7%) were saccular in morphology. The median greatest dimension of contrast filling was 17 (IQR, 12.5e30) mm with a median greatest axial diameter on MRI or CT of 17 (IQR, 14e28) mm. When compared with aneurysms with <50% thrombosis, pretreatment CN dysfunction was less common (33.3% vs. 60.6%, P ¼ 0.063) and complete occlusion at last radiographic follow-up was significantly less common (58.8% vs. 87.1%, P ¼ 0.026). There was a trend toward better functional outcome (mRS 2) at last WORLD NEUROSURGERY, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.11.084 ORIGINAL ARTICLE PAUL M. FOREMAN ET AL. Figure 2. A 77-year-old woman with partially thrombosed right ACA aneurysm. (A) Pretreatment DSA. (B) DSA after adjunctive coiling. (C) DSA after deployment of a PED in the A1 segment of the ACA, spanning the neck of the aneurysm. (D) Follow-up DSA at 6 months demonstrates follow-up in patients with <50% pretreatment aneurysm thrombosis (96.8 vs. 82.4, P ¼ 0.08) (Table 4). Multivariable Predictors of Incomplete Occlusion Based on potential predictors on univariate screening (Table 3), a multivariable logistic regression model was constructed to identify predictors of incomplete occlusion, controlling for amount of aneurysmal thrombosis (>50% vs. <50%), age, maximal diameter, smoking history, and procedural complete neck coverage. Age (1-year increments) maintained its independent significance (P ¼ 0.05), whereas amount of aneurysmal thrombosis trended in the same direction but lost independent significance (P ¼ 0.09), likely in the setting of a small sample size being underpowered to detect significance. Similarly, 1-mm increments increase in maximal diameter trended toward incomplete occlusion but did not reach statistical significance (P ¼ 0.06). Of note, the results of the multivariable model should be interpreted WORLD NEUROSURGERY 135: e164-e173, MARCH 2020 FLOW DIVERSION FOR THROMBOSED ANEURYSMS complete aneurysm occlusion. (E) 3D reconstruction of DSA demonstrates complete aneurysm occlusion. ACA, anterior cerebral artery; DSA, digital subtracted angiography; PED, Pipeline Embolization Device. tentatively given the small sample size and even smaller number of events (i.e., incomplete occlusion), which can limit the stability of the model. We tried to avoid overfitting by including 5 covariates only for 50 observations (following the rule of thumb of minimum of 10 subjects for each model covariate, while trying to account for interactions and collinearity between the variables). However, we had to eliminate other literature-known potential important predictors such as gender, fusiform morphology, and circulation (anterior vs. posterior) (Table 5). DISCUSSION This study represents the largest series of PTIA treated with placement of flow diverting stents to date. Inclusion of 50 patients across 6 cerebrovascular treatment centers highlights the rarity of the diagnosis. Thromboembolic complications occurred in 9.8%, with a fatal ischemic stroke in 2 patients. Complete aneurysm www.journals.elsevier.com/world-neurosurgery e169 ORIGINAL ARTICLE PAUL M. FOREMAN ET AL. FLOW DIVERSION FOR THROMBOSED ANEURYSMS Table 3. Comparison According to Last Follow-Up Aneurysm Occlusion Status Complete Occlusion, 37 (77.1%) Incomplete Occlusion, 11 (22.9%) P Value Age (years), median (IQR) 55 (46e63) 70 (62e70) 0.015 Female sex 23 (62.2%) 7 (63.6%) 0.9 Saccular 24 (64.9%) 8 (72.7%) 0.47 Fusiform/dolichoectatic 12 (32.4%) 2 (18.2%) Variable Morphology 1 (2.7%) 1 (9.1%) Filling size (greatest dimension of contrast filling) (mm)* Multilobulated 12 (8e17) 14 (11e20) 0.49 Axial size (greatest diameter on axial MRI or CT including thrombosed portion) (mm)* 16 (12e22) 22.5 (17e28) 0.065 27 (73%) 4 (36.4%) 0.026 Pretreatment aneurysmal thrombosis <50% >50% Multiple aneurysms Family history of aneurysms 10 (27%) 7 (63.6%) 11 (29.7%) 8 (72.7%) 0.01 1 (2.7%) 1 (9.1%) 0.35 19 (51.4%) 5 (45.5%) 0.008 Smoking history Never smokers Past smokers 3 (8.1%) 5 (45.5%) 15 (40.5%) 1 (9.1%) 19 (51.4%) 6 (54.6%) 0.85 None 32 (86.5%) 10 (90.9%) 0.7 Endovascular treatment Current smokers Cranial nerve dysfunction at presentation Previous treatment history 5 (13.5%) 1 (9.1%) Adjunct coiling 8 (21.6%) 1 (9.1%) 0.09 Complete neck coverage after deployment 34 (91.1%) 8 (72.7%) 0.09 Outcomes Time to last imaging follow-up (months), median (IQR) 25.4 (11.9e42.1) 24.8 (14.5e49.5) 0.45 2 35 (94.6%) 9 (81.8%) >2 2 (5.4%) 2 (18.2%) 0 (0%) 6 (54.5%) <0.001 3 (8.1%) 1 (9.1%) 0.92 0 (0%) 0 (0%) NA mRS on last follow-upy Retreatment Post-treatment ischemic complications Post-treatment hemorrhagic complications 0.18 Bold value denotes statistical significance; i.e., P < 0.05. CT, computed tomography; IQR, interquartile range; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mRS, modified Rankin scale. *Measurements: median (IQR); P value: Mann-Whitney test. yMissing data for 2 patients. occlusion was observed in 77.1% of aneurysms at a median followup of 25.1 months. Aneurysms with 50% thrombosis noted on pretreatment imaging were associated with lower rates of complete occlusion, despite losing significance on multivariable likely to underpowering. Interestingly, of all the 9 ruptured aneurysms e170 www.SCIENCEDIRECT.com were <50% thrombosed (27.3% vs. 0%, P ¼ 0.015), suggesting that risk of rupture might be independent of the amount of thrombus harbored in the aneurysm, despite this group having potentially more favorable angiographic outcome in response to flow diversion. WORLD NEUROSURGERY, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.11.084 ORIGINAL ARTICLE PAUL M. FOREMAN ET AL. FLOW DIVERSION FOR THROMBOSED ANEURYSMS Table 4. Comparison According to Pretreatment Aneurysm Thrombosis ‡50%, 18 (35.3%) <50%, 33 (64.7%) P Value Age (years), median (IQR) 65 (59e73) 53 (46e61) 0.01 Female sex 13 (72.2%) 18 (54.6%) 0.67 Saccular 12 (66.7%) 21 (63.6%) 0.8 Fusiform/dolichoectatic 5 (27.8%) 11 (33.3%) Multilobulated 1 (5.6%) 1 (3%) 17 (12.5e30) 15 (9e17) 0.86 17 (14e28) 18 (12e22) 0.56 Multiple aneurysms 7 (38.9%) 12 (36.4%) 0.86 Family history of aneurysms 1 (5.6%) 1 (3%) 0.65 Never smokers 10 (55.6%) 16 (48.5%) 0.8 Past smokers 3 (16.7%) 5 (15.2%) Current smokers 5 (27.8%) 12 (36.7%) 6 (33.3%) 20 (60.6%) 0.063 0 (0%) 9 (27.3%) 0.015 17 (94.4%) 27 (81.8%) 0.2 1 (5.6%) 6 (18.2%) 4 (22.2%) 12 (36.4%) Variable Morphology Filling size (greatest dimension of contrast filling) (mm)* Axial size (greatest diameter on axial MRI or CT including thrombosed portion) (mm)* Smoking history Cranial nerve dysfunction at presentation Ruptured at presentation Previous treatment history None Endovascular treatment Adjunct coiling 0.3 Outcomes Time to last imaging follow-up (months), median (IQR) 24.3 (11.8e33.1) 28.5 (13.6e46.5) 0.2 Complete occlusion 10 (58.8%) 27 (87.1%) 0.026 Incomplete occlusion 7 (41.2%) 4 (12.9%) 2 14 (82.4%) 30 (96.8%) >2 3 (17.6%) 1 (3.2%) Occlusion at last imaging follow-upy mRS on last follow-upy 0.08 Retreatment 4 (22.2%) 3 (9.1%) 0.19 Post-treatment ischemic complications 2 (11.1%) 3 (9.1%) 0.81 0 (0%) 1 (3%) 0.46 Post-treatment hemorrhagic complications n (%); P value: c2 test. Bold values: P value <0.05. CT, computed tomography; IQR, interquartile range; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mRS, modified Rankin scale. *Measurements: median (IQR); P value: Mann-Whitney test. yMissing data for 2 patients. The pathophysiology of PTIA is incompletely understood, yet believed distinct from classic “berry aneurysms” with abluminal factors playing an important role in their development and WORLD NEUROSURGERY 135: e164-e173, MARCH 2020 growth.9 Adventitial inflammation with release of proinflammatory factors into the arterial wall media leads to degradation of the extracellular matrix and elastic lamina, and www.journals.elsevier.com/world-neurosurgery e171 ORIGINAL ARTICLE PAUL M. FOREMAN ET AL. FLOW DIVERSION FOR THROMBOSED ANEURYSMS Table 5. Logistic Regression Model for Odds of PTIA Incomplete Occlusion After Flow Diversion, Controlling for Preaneurysmal Thrombosis, Age, Size, Smoking, and Procedural Neck Coverage Variable OR 95% CI P Value Pretreatment aneurysmal thrombosis (>50% vs. <50%) 3.5 0.83e20.8 0.09 Age, 1-year increments 1.08 1.000e1.16 0.05 Maximal diameter, 1-mm increments 1.07 0.995e1.15 0.06 Smoking 2.1 0.37e12.1 0.4 Procedural complete neck coverage 0.16 0.017e1.47 0.1 Bold value denotes statistical significance; i.e., P < 0.05. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PTIA, partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms. initiates the multistep process of aneurysm formation.9 Recurrent microdissections of the weakened pathogenic arterial wall then result in subadventitial hemorrhage and intramural thrombus with subsequent formation of intraluminal thrombus.1,10 Relative contributions of the vasa vasorum, perfused intrathrombotic clefts, and proliferating intrathrombotic endothelial channels to aneurysm growth and symptomatology are debated.1,11-14 The unique pathophysiology of PTIA carries potential therapeutic implications and could underlie the unsatisfactory results of surgical reconstruction and endovascular embolization with detachable coils. Surgical management of PTIA involves clip reconstruction with or without aneurysm thrombectomy and parent artery/aneurysm occlusion with or without arterial bypass. These cases present unique technical challenges due to intra-aneurysmal thrombus and are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, even in experienced hands.2 Cases amendable to direct surgical clipping produce the best surgical results.2 However, defining the lesional arterial segment intraoperatively remains challenging and can lead to inclusion of pathogenic vessel segments within the reconstructed parent artery, increasing the rate of recurrence.10 Standard endovascular treatment options for PTIA are less technically challenging, and include coil embolization and parent artery occlusion after balloon test occlusion. Selective coil embolization of these aneurysms has yielded disappointing results with recanalization rates as high as 78%, often due to coil migration into the intraluminal thrombus necessitating retreatment5,6; continued aneurysm growth resulting in a high mortality rate was also reported.6 Although continued aneurysm growth after parent artery occlusion has been reported,13 strategies that include parent artery occlusion have yielded superior results when compared with strategies that address only the perfused aneurysmal sac.6,10 Parent artery occlusion resulted in significantly higher rates of neurologic improvement, aneurysm size reduction, and durable aneurysm occlusion.6,10 Despite encouraging results, parent artery occlusion is not always tolerated and can be precluded by aneurysm location. Endovascular parent artery reconstruction with flow diverting stents is a promising treatment modality for PTIA. The technique involves placement of the flow diverter within the parent artery e172 www.SCIENCEDIRECT.com avoiding potential hazards of entering or manipulating the aneurysm. In addition, aneurysm occlusion is ultimately achieved by endothelialization of the stent across the neck of the aneurysm, therefore overcoming the recanalization rates seen with detachable coils. Safety and efficacy of flow diversion for the treatment of large and giant aneurysms has been previously demonstrated,15,16 with 1- and 5-year angiographic occlusion rates of 87% and 95%, respectively, in the Pipeline for Uncoilable or Failed Aneurysm Trial17; however, PITA constituted only 15.7% of the Pipeline for Uncoilable or Failed Aneurysm Trial population, and the outcomes were not specifically assessed in this subgroup. Resolution of radiographic mass effect with improvement of CN compression syndromes, including patients with large and giant PTIA, has also been reported.18,19 The present series observed a complete occlusion rate of 77% over a median follow-up of 25 months, with 45% of patients experiencing improvement of pretreatment CN dysfunction. Underlying differences in the pathophysiology of PTIA potentially account for the reduced efficacy of flow diversion when compared with other series. Postmortem histopathology of large aneurysms treated with flow diversion has supported the theory that intra-aneurysmal thrombus induces transient destabilization of the aneurysm wall via mechanisms of hypoxia, inflammation, and enzymatic degredation.20 Erythrocyte-rich thrombus, in particular, is known to promote an inflammatory milieu of lytic enzymes produced by activated leukocytes.21 This thrombus-initiated inflammatory process potentially retards progressive endothelialization of the flow diverting stent leading to higher rates of incomplete occlusion in aneurysms with a large amount of pretreatment thrombus. Long-term follow-up is necessary to determine if the observed trend of progressive occlusion over time will be seen in PTIA. Limitations The present study is limited by its retrospective design, nonstandardized follow-up, and lack of independently adjudicated outcomes. The retrospective design of the study allows for patient selection bias with the decision to treat a particular PTIA left to the discretion of the treating physician. Lack of standardized followup is of particular interest with flow diversion treatment of aneurysms due to the progressive, time-dependent nature of aneurysm occlusion. Retrospective studies that lack independent WORLD NEUROSURGERY, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.11.084 ORIGINAL ARTICLE PAUL M. FOREMAN ET AL. FLOW DIVERSION FOR THROMBOSED ANEURYSMS adjudication of outcomes tend to overestimate safety and efficacy in surgical and interventional series. The inclusion of cases from 5 international centers allowed us to amass a modest number of cases for a rare disease process and improves the generalizability of the study. The broad inclusion criteria allowed for a practical and comprehensive evaluation of flow diversion for the treatment of PTIA. CONCLUSIONS Flow diversion treatment of PTIA carries adequate efficacy along with a reasonable safety profile. Aneurysms with 50% pretreatment thrombosis were associated with lower rates of complete occlusion. The unique pathophysiology of PTIA development and growth is hypothesized to contribute to the reduced efficacy when compared with treatment of “berry aneurysms.” Considering the challenges of treating large and giant partially thrombosed aneurysms, the results support the use of flow diverting stent for these aneurysms. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Paul M. Foreman contributed to conceptualization, methodology writing, and reviewing; Mohamed M. Salem to methodology, writing, software, and formal analysis; Christoph J. Griessenauer to methodology and data curation; Adam A. Dmytriw, Carmen Parra-Farinas, Patrick Nicholson, Nicola Limbucci, Anna Luisa Kühn, and Ajit S. Puri to data curation; Leonardo Renieri to visualization and reviewing; Sergio Nappini to visualization, reviewing, and resources; Kimberly P. Kicielinski and Alejandro Bugarini to reviewing and data curation; Vitor Mendes Pereira to editing; Thomas R. Marotta and Clemens M. Schirmer to investigation and supervision; Christopher S. Ogilvy to conceptualization and resources; and Ajith J. Thomas contributed to conceptualization, supervision, and resources. delayed aneurysm rupture after flow-diversion treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:20-25. 9. Krings T, Piske RL, Lasjaunias PL. Intracranial arterial aneurysm vasculopathies: targeting the outer vessel wall. Neuroradiology. 2005;47:931-937. 17. Becske T, Brinjikji W, Potts MB, et al. Long-term clinical and angiographic outcomes following Pipeline Embolization Device treatment of complex internal carotid artery aneurysms: five-year results of the Pipeline for Uncoilable or Failed Aneurysm Trial. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:40-48. 10. Yang K, Park JC, Ahn JS, Kwon DH, Kwun BD, Kim CJ. Characteristics and outcomes of varied treatment modalities for partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms: a review of 35 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2014;156:1669-1675. 18. Szikora I, Marosfoi M, Salomvary B, Berentei Z, Gubucz I. Resolution of mass effect and compression symptoms following endoluminal flow diversion for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:935-939. 3. Guresir E, Wispel C, Borger V, Hadjiathanasiou A, Vatter H, Schuss P. Treatment of partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms: single-center series and systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2018;118:e834-e841. 11. Schubiger O, Valavanis A, Wichmann W. Growthmechanism of giant intracranial aneurysms; demonstration by CT and MR imaging. Neuroradiology. 1987;29:266-271. 19. Zanaty M, Jabbour PM, Bou Sader R, et al. Intraaneurysmal thrombus modification after flowdiversion. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:105-110. 4. Cho YD, Park JC, Kwon BJ, Hee Han M. Endovascular treatment of largely thrombosed saccular aneurysms: follow-up results in ten patients. Neuroradiology. 2010;52:751-758. 12. Nagahiro S, Takada A, Goto S, Kai Y, Ushio Y. Thrombosed growing giant aneurysms of the vertebral artery: growth mechanism and management. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:796-801. 5. Kim SJ, Choi IS. Midterm outcome of partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms treated with guglielmi detachable coils. Interv Neuroradiol. 2000; 6:13-25. 13. Iihara K, Murao K, Sakai N, et al. Continued growth of and increased symptoms from a thrombosed giant aneurysm of the vertebral artery after complete endovascular occlusion and trapping: the role of vasa vasorum. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:407-413. REFERENCES 1. Krings T, Alvarez H, Reinacher P, et al. Growth and rupture mechanism of partially thrombosed aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol. 2007;13:117-126. 2. Lawton MT, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Chang EF, Yu T. Thrombotic intracranial aneurysms: classification scheme and management strategies in 68 patients. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:441-454 [discussion: 441-454]. 6. Ferns SP, van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, van den Berg R, Majoie CB. Partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms presenting with mass effect: long-term clinical and imaging follow-up after endovascular treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:1197-1205. 7. Chow M, McDougall C, O’Kelly C, Ashforth R, Johnson E, Fiorella D. Delayed spontaneous rupture of a posterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysm following treatment with flow diversion: a clinicopathologic study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:E46-E51. 8. Kulcsar Z, Houdart E, Bonafe A, et al. Intraaneurysmal thrombosis as a possible cause of 14. Yasui T, Sakamoto H, Kishi H, et al. Rupture mechanism of a thrombosed slow-growing giant aneurysm of the vertebral artery—case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1998;38:860-864. 15. Becske T, Kallmes DF, Saatci I, et al. Pipeline for Uncoilable or Failed Aneurysm: results from a multicenter clinical trial. Radiology. 2013;267: 858-868. 16. Nelson PK, Lylyk P, Szikora I, Wetzel SG, Wanke I, Fiorella D. The Pipeline Embolization Device for the intracranial treatment of aneurysms trial. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:34-40. WORLD NEUROSURGERY 135: e164-e173, MARCH 2020 20. Chyatte D, Bruno G, Desai S, Todor DR. Inflammation and intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:1137-1146 [discussion: 1146-1137]. 21. Turowski B, Macht S, Kulcsar Z, Hanggi D, Stummer W. Early fatal hemorrhage after endovascular cerebral aneurysm treatment with a flow diverter (SILK-Stent): do we need to rethink our concepts? Neuroradiology. 2011;53:37-41. Conflict of interest statement: M. M. Salem is a former recipient of research financial support from Medtronic Inc., Cerebrovascular Group. The rest of the authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest with regard to the authorship and/or publication of this manuscript. Received 28 August 2019; accepted 14 November 2019 Citation: World Neurosurg. (2020) 135:e164-e173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.11.084 Journal homepage: www.journals.elsevier.com/worldneurosurgery Available online: www.sciencedirect.com 1878-8750/$ - see front matter ª 2019 Published by Elsevier Inc. www.journals.elsevier.com/world-neurosurgery e173