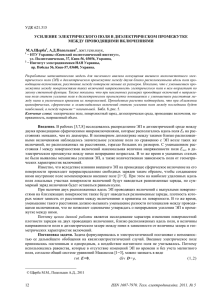

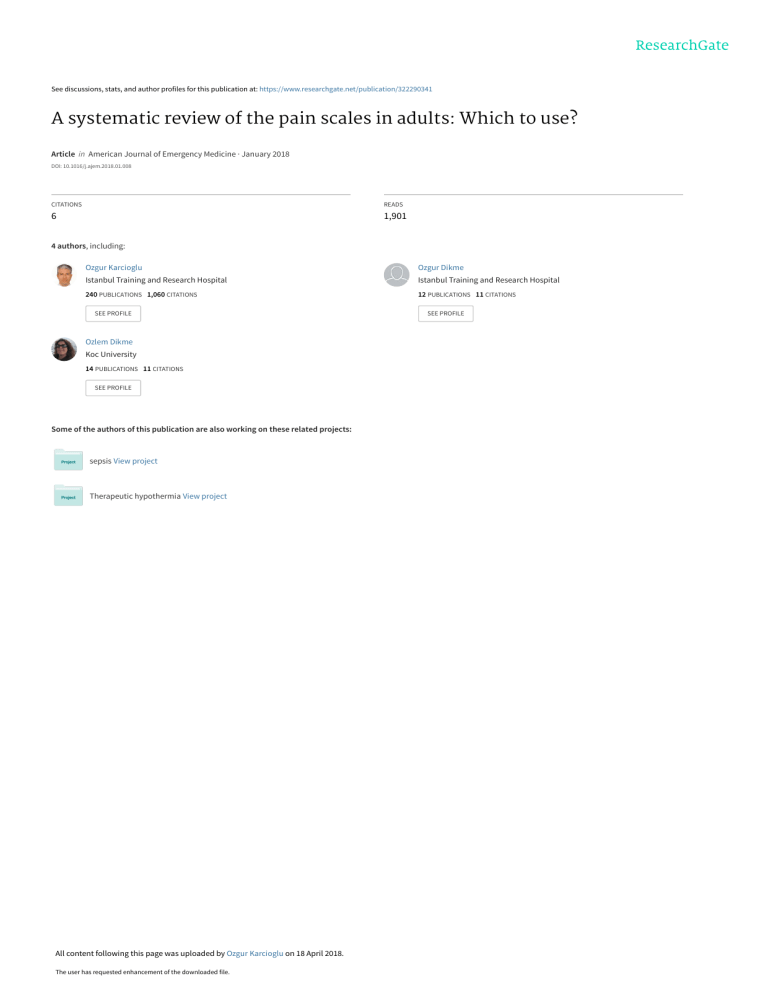

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322290341 A systematic review of the pain scales in adults: Which to use? Article in American Journal of Emergency Medicine · January 2018 DOI: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.01.008 CITATIONS READS 6 1,901 4 authors, including: Ozgur Karcioglu Ozgur Dikme Istanbul Training and Research Hospital Istanbul Training and Research Hospital 240 PUBLICATIONS 1,060 CITATIONS 12 PUBLICATIONS 11 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Ozlem Dikme Koc University 14 PUBLICATIONS 11 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: sepsis View project Therapeutic hypothermia View project All content following this page was uploaded by Ozgur Karcioglu on 18 April 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (2018) 707–714 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect American Journal of Emergency Medicine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ajem Review A systematic review of the pain scales in adults: Which to use? Ozgur Karcioglu a,⁎, Hakan Topacoglu b, Ozgur Dikme a, Ozlem Dikme c a b c University of Health Sciences, Istanbul Training and Research Hospital, Emergency Department, Fatih, Istanbul, Turkey Duzce University, School of Medicine, Emergency Department, Duzce, Turkey Koc University, School of Medicine, Emergency Department, Istanbul, Turkey a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 26 December 2017 Accepted 3 January 2018 Keywords: Acute pain Pain score Pain scale Pain intensity Pain management Emergency department a b s t r a c t Objective: The study analysed the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), the Verbal Rating Scale (VRS) and the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) to determine: 1. Were the compliance and usability different among scales? 2. Were any of the scales superior over the other(s) for clinical use? Methods: A systematic review of currently published studies was performed following standard guidelines. Online database searches were performed for clinical trials published before November 2017, on the comparison of the pain scores in adults and preferences of the specific patient groups. A literature search via electronic databases was carried out for the last fifteen years on English Language papers. The search terms initially included pain rating scales, pain measurement, pain intensity, VAS, VRS, and NRS. Papers were examined for methodological soundness before being included. Data were independently extracted by two blinded reviewers. Studies were also assessed for bias using the Cochrane criteria. Results: The initial data search yielded 872 potentially relevant studies; of these, 853 were excluded for some reason. The main reason for exclusion (33.7%) was that irrelevance to comparison of pain scales and scores, followed by pediatric studies (32.1%). Finally, 19 underwent full-text review, and were analysed for the study purposes. Studies were of moderate (n = 12, 63%) to low (n = 7, 37%) quality. Conclusions: All three scales are valid, reliable and appropriate for use in clinical practice, although the VAS is more difficulties than the others. For general purposes the NRS has good sensitivity and generates data that can be analysed for audit purposes. © 2018 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1. Pain in the emergency department Acute pain is one of the most common chief complaints reported by most patients admitted to the ED, while its perception and expression have great variations between countries [1]. The definition of pain by International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage’ is accepted worldwide [2]. Subjective and multidimensional nature of the pain experience render pain assessment really challenging. In the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) guidelines, implementation of this standard in clinical practice comprised the addition of pain as the “fifth” vital sign to be noted in the context of initial assessment; the use of pain intensity ratings; and posting of a statement on pain management in all patient care areas. Supplemented with regular pain reassessments, the schedule of pain reassessment should be driven by patients' pain severity [3]. ⁎ Corresponding author at: Dept. of Emergency Medicine, Univ. of Health Sciences, Istanbul Education and Research Hospital, PK 34098, Fatih, Istanbul, Turkey. E-mail address: [email protected] (O. Karcioglu). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.01.008 0735-6757/© 2018 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Pain estimations need to be elicited and recorded to highlight both the presence of pain and the efficacy of pain treatment. The patients' perception of pain should be documented during the initial assessment of a patient. Current evidence provides a general recommendation that pain needs to be evaluated and managed within 20–25 min of initial healthcare provider assessment in the ED [4]. Pain treatment should be targeted to a goal of reducing the pain score (e.g., by 50%, below 4/ 10, or referred to as mild/moderate or severe) rather than a specific analgesic dose [5]. 2. Pain scores and documentation of pain The patient's self-report is the most accurate and reliable evidence of the existence of pain and its intensity, and this holds true for patients of all ages, regardless of communication or cognitive deficits [6]. In the absence of objective measures, the clinician must depend on the patient to supply key information on the localization, quality and severity of the pain. Although physicians commonly question the reported severity and rely on their own estimates, the value of the patients' description of the location and nature of the discomfort has been proved on the theoretical basis and routine practice [7]. 708 O. Karcioglu et al. / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (2018) 707–714 Pain scores have gained acceptance as the most accurate and reliable measure of assessing a patient's pain and response to pain treatment [5]. Scales devised to estimate and/or express the patient's pain can be evaluated in two groups: Unidimensional and multidimensional measures. It should be noted that unidimensional scales measure only intensity, they cannot be viewed as a comprehensive pain assessment. Comprehensive pain assessment is expected to encompass both the unidimensional measurement of pain intensity and the multidimensional evaluation of the pain perception. The unidimensional pain intensity scales commonly used bedsides are: • Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), • Visual Analog Scale (VAS), • Verbal Rating/Descriptor Scale (VRS/VDS). • 4–6 = moderate pain • 7–10 = severe pain NRS can be used with most children older than 8 years of age, and behavioral observation scales are required for those unable to provide a self-report [15]. For patients with cancer-related pain, the NRS is the most frequently used instrument to measure pain intensity [16]. Goulet et al. examined the agreement and correlation of electronic medical record-based ratings of NRS and self-administered NRS in 1643 adult patients [17]. The correlation was high, but the mean electronic medical record-based NRS score was significantly lower than the survey score (1.72 vs. 2.79; p b 0.0001). 2.3. B.3 2.1. B.1 The VAS is the most widely used tool for estimating both severities of pain and to judge the extent of pain relief [8]. Healthcare worker asks the patient to select a point on a line drawn between two ends to express how intense he/she perceives pain (Fig. 1). The VAS is a continuous scale comprised of a horizontal (HVAS) or vertical (VVAS) line, usually 100 mm long, anchored by two verbal descriptors (i.e., “no pain” and “worst imaginable pain”) [9, 10]. Patients are asked to rate “current” pain intensity or pain intensity “in the last 24 h”. The VAS is an easy-to-use instrument which does not warrant using a sophisticated device. It is also highly sensitive in detecting treatment effects, and its results can be analysed by parametric tests [11]. Minimal translation difficulties have led to an unknown number of cross-cultural adaptations [10]. Although this tool is suitable for use with older children and adults, the need for a marking and for being able to visualize and mark the line, can make the VAS impractical to use in the emergency situation. On the other hand, most experts believe that the VAS offers little practical advantage over verbal reports in the clinical practice [5]. Verbal Pain Scores (VPSs), Verbal Rating Scales (VRS) or Verbal Descriptor Scales: These tools may discern those patients who are truly in pain but who may not express their discomfort, as well as influence the physician to inquire about the patient's pain. VRS consist of a number of statements describing increasing pain intensities (Fig. 1). Patients are told to choose the word which best describes their pain intensity. The number of descriptors used has ranged from four (none, mild, moderate, severe) to 15 [18]. For patients who have limited literacy or cognitive impairment, use of these scales may be difficult, and they do not provide the number of choices available with the VAS or NRS, thus potentially limiting precision [19]. This article reviews the current literature to provide systematic data regarding the results from comparative studies on unidimensional assessment of pain intensity using the NRS, VRS, or VAS. The following points were investigated to determine evidence-based recommendations: - Were the compliance and usability different among scales? - Were any of the scales superior over the other(s) for clinical use? 3. Methods 2.2. B.2 The numeric rating scale (NRS) is a single 11-point numeric scale broadly validated across myriad patient types. Data obtained via NRS are easily documented, intuitively interpretable, and meet regulatory requirements for pain assessment and documentation [12]. To date, findings demonstrated that even in the chaotic prehospital phase most acute care patients allow evaluation via a simple “zero-to-10 scale” or NRS reliably, respecting their pain levels [13]. Like the pain VAS, minimal language translation difficulties support the use of the NRS across cultures and languages [14]. Evidence indicated that patients really want to give a pain number, rather than simply relate whether they want analgesia. Strengths of this measure over the pain VAS are the ability to be administered both verbally (therefore by telephone) and in writing, as well as its simplicity of scoring. However, similar to the pain VAS, the pain NRS evaluates only 1 component of the pain experience, pain intensity, and therefore does not capture the complexity and idiosyncratic nature of the pain experience or improvements due to symptom fluctuations [10]. NRS is a commonly used tool necessitating the patient rate his pain on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 reflecting the worst possible pain (Fig. 2). NRS are often conducted as a scale from 1 to 10 which does not give the patient a solution to indicate no pain at all. It can be used with children who are able to understand numbers. The pain scores are interpreted as: • 0 = no pain • 1–3 = mild pain A systematic review of currently published studies was performed following standard guidelines. Online database searches were performed for randomized controlled trials published before November 2017, on the comparison of the pain scores in adults and preferences of the specific patient groups. A literature search via the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed/Medline, Clinical Key, EMBASE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and BIOSIS was carried out for the last fifteen years on English Language papers. Published studies evaluating the patients' preferences and usability of the pain intensity scales were targeted. The reference lists of retrieved articles were used to generate more papers and search terms. Data were independently extracted by two blinded reviewers. The discrepancies, on the other hand, were resolved by the primary author. The research protocol to answer these questions was registered in PROSPERO, the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number is: CRD42017080974). 3.1. Search methodology A comprehensive literature search was carried out using the following strategy: Online searches were performed using the following search keywords and terms: (‘pain assessment’ OR ‘pain intensity’ OR ‘pain score’ OR ‘pain comparison’ OR ‘pain scale’ OR ‘acute pain’ OR ‘pain rating’) AND (‘emergency’ AND ‘acute’ AND ‘score’). The search was limited to human studies (clinical trials) conducted on adults and published in English. O. Karcioglu et al. / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (2018) 707–714 709 A B C D Fig. 1. A. Visual Analog Scale (VAS). B. The Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) C. Verbal Rating Scale (VRS) or Verbal DescriptorScale (VRS). D. FACES Pain Rating Scale. 3.2. Study selection, data screening and critical appraisal The study included all comparative trials conducted to assess the use of commonly used scales measuring acute pain intensity and to compare them with each other on specific patient groups, exclusively in adults. All RCTs of any duration that investigated pain scores in comparison to each other were identified. All potentially eligible papers were critically appraised, with the emphasis on evidence from randomized trials and international guidelines rather than smaller studies, case series and case reports. Reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and all included studies were checked to identify additional eligible articles. Conference abstracts and proceedings were not deemed eligible for inclusion in the review. Citation titles and abstracts were independently screened and assessed regarding the methodological quality by two reviewers (H.T. and O.D.). Any disagreements between the two reviewers were then resolved by consensus or in consultation with a third reviewer (O.K.) if needed. 3.3. Quality assessment and risk of bias Eligible clinical studies were rated regarding the quality of evidence as per GRADE guidelines and assigned to one of four groups: High (A), moderate (B), low (C) and very low (D) quality [20]. Studies that met the inclusion criteria for the review were assessed for bias using the risk of bias criteria developed by Cochrane's EPOC group [21] which is based upon Cochrane's Risk of Bias Tool [22]. Studies were assessed with regard to selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other sources of bias. Studies were rated as “low risk of bias (L)”, “high risk of bias (H),” or “unclear risk of bias (U)” on a general impression after evaluating all criteria (Table 1). 4. Results The initial electronic data search yielded a total of 872 potentially relevant studies; of these, 853 were excluded for some reason, and finally 19 trials fully met the selection criteria based on inclusion of information regarding comparative data on the pain scales, and specific populations' preferences on the scales (Fig. 2). The main reason for exclusion (33.7%, 288/853) was that irrelevance to comparison of pain scales and scores, followed by pediatric studies (32.1%, 274/853). Data collected for the review of the 19 clinical studies included in the analysis of the pain scales used in the acute setting were tabulated and summarized (Table 1). With respect to quality of evidence per GRADE guidelines, there were 12 (63%) moderate quality (B) and 7 (37%) low quality (C) evidence derived from the studies. 710 O. Karcioglu et al. / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (2018) 707–714 Fig. 2. Flow diagram of study selection for systematic review to compare the clinical use of three commonly used pain rating scales, namely the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), the Verbal Rating Scale (VRS) and the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS). 5. Discussion In order to use pain-rating scales well clinicians need to appreciate the potential for error within the tools, and the potential they have to provide the required information. Interpretation of the data from a pain-rating scale is not as straightforward as it might first appear. Leigheb M, et al. pointed out that there is substantial discordance between NRS and VAS scores which is suggestive of a need for clinical judgment to be incorporated into assessment of actual pain intensity and concluded that leaning on pain scale data alone is not a comprehensive approach [23]. In the present study, most of the studies in the analysis indicated a good correlation between VAS, VRS/VDS and NRS, although some pointed out there is a discrepancy in some situations. One study reported a moderate agreement between calculated percentage pain reduction from a VAS or NRS and the difference could range up to 30%. VDS and NRS were also found to have strong correlation and can be used in practice depending on the preference. The elderly were found to prefer VDS to express their pain intensity [24, 25] including those with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. Accordingly, Ware et al. reported that NRS was the preferred scale in the cognitively intact group while FPS-R was the preferred scale in the cognitively impaired group [26]. A number of studies cited a considerable difficulty in practical use of VAS, especially in the elderly and populations with disadvantages. For example, Yazici et al. noted that the NRS, TPS, FPS, and VDS were appropriate pain rating scales for the participants in this study, and that the VAS should be used in combination with one of these scales [27]. One of the first reviews on comparison of the three pain scales (VAS, VRS, and NRS) were published by Williamson and Hoggart in 2005 and they reported that all three scales were valid, reliable and appropriate for use, although the VAS had more practical difficulties than the other two scales [28]. They stressed that for general purposes the NRS has good sensitivity and produces data that can be analysed for audit purposes. Likewise, Hjermstad MJ, et al. performed a systematic review of studies to culminate data on the use and performance of unidimensional pain scales [29]. They reported that when compared with the VAS and VRS, NRSs had better compliance in 15 of 19 studies reporting this, and were the recommended tool in 11 studies. Overall, NRS and VAS scores O. Karcioglu et al. / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (2018) 707–714 711 Table 1 Main characteristics of the outstanding human studies that were explained and reviewed in the present study. Investigator(s), Sample size and title and population date, Ref. # Quality of Risk Objectives evidence of (GRADE)⁎ bias⁎⁎ Findings McLean, et al. 2004. [13] 1227 prehospital patients N13 yrs old C H To determine the feasibility of prehospital pain measurement among patients 13 yrs of age or older using a VRS and NRS. Leigheb M, et al. 2017. [23] 137 adult ED patients B H Pereira et al. 2015. [24] C 101 institutionalized elderly U To evaluate the intensity and location of pain experienced by patients in the ED, the time to analgesic therapy in the ED, and the patient's satisfaction so to identify potential interventions to improve management Correlating two unidimensional scales for measurement of self-reported pain intensity for elderly and identifying a preference for one of the scales. Herr KA, et al. 2004. [25] B 175 86 younger (age 25-55) and 89 older (N65) adults U To determine: (1) the psychometric properties and utility of 5 types of commonly used pain rating scaleswhen used with younger and older adults, (2) factors related to failure to successfully use a pain rating scale, (3) pain rating scale preference, and (4) factors impacting scale preference. Ware LJ, et al. 2006. [26] 68 cognitively impaired minority sample C H To determine the reliability and validity of selected pain intensity scales including the FPS-R, VDS, NRS, and Iowa Pain Thermometer (IPT) with a cognitively impaired minority sample. Yazici et al. 2014. [27] 621 postoperative adult patients B L To determine patient pain scale preferences and compare the level of agreement among pain scales commonly used during postoperative pain assessment. Bahreini M, et al. 2015. [30] 150 adult ED patients C H To assess the agreement between VAS, Color Analog Scale (CAS), and NRS in the emergency setting. Aziato L, et al. 2015. [31] 150 post-operative patients B L To select, develop, and validate context-appropriate unidimensional pain scales for pain assessment among adult post-operative patients. An 11-point scale is preferable for prehospital practice and could also be useful for research applications. Pain assessment using a VRS and NRS can be implemented with minimal paramedic training. The discrepancy between NRS and The magnitude of NRS pain measurements were higher than VAS VAS scores suggests that painintensity cannot be determined accurately measurements. according topainscaledata alone but should also incorporate clinical judgment. Pain measurements among There were moderate to strong, institutionalized elderly can be made positive and statistically significant by NRS and VDS; however, the associations between the scores of NRS and VDS: overall assessment (r = preferred scale for the elderly was the VDS, regardless of gender. 0.75), the rest (r = 0.92) and movement (r = 0.87). Higher mean scores were associated in NRS to higher categories of pain intensity in VDS. The association between the mean scores of NRS with the categories of VDS was significant, indicating convergent validity and a similar metric between the scales. Although all 5 of the pain intensity All 5 pain scales (VAS, FPS, VDS, rating scales were psychometrically 21-point NRS, 11-point VNS) were sound when used with either age effective in discriminating different levels of pain sensation; however the group, failures, internal consistency reliability, construct validity, scale VDS was most sensitive and reliable. Failure rates for pain scale completion sensitivity, and preference suggest that the VDS is the scale of choice for were minimal, except for the VAS. The scale most preferred to represent assessing pain intensity among older adults, including those with mild to pain intensity in both cohorts of subjects was the NRS, followed by the moderate cognitive impairment. VDS. Concurrent validity was supported In terms of pain scale preference, the with correlations ranging from 0.56 to NRS (33%) was the preferred scale in the cognitively intact group and the 0.90. The lowest correlations were FPS-R (54%) was the preferred scale in found between the FPS-R and the other scales, suggesting that the FPS-R the cognitively impaired group. may be measuring a broader construct African-Americans and Hispanics preferred the FPS-R. Severely, incorporating pain moderately, and mildly impaired participants also preferred the FPS-R. The NRS, TPS, FPS, and VDS were Patient preference for pain scales were as follows: 97.4% FPS, 88.6% NRS, appropriate pain rating scales for the participants in this study, and that the 84.1% VDS, 78.1% TPS, 60.1% SFMPQ, 37.0% BPI, 11.4% VAS, and 10.5% MPQ. VAS should be used in combination Education was an important factor in with one of these scales. the preferences for all scales (p b .000). The level of pain determined by the VAS did not correlate with the level of pain identified by the NRS, TPS, FPS, and VDS (p b .05). Spearman correlation coefficients The three pain scales were strongly between NRS and CAS, NRS and VAS, correlated at all time periods. The and CAS and VAS were 0.95, 0.94, and findings suggest that NRS, CAS, and 0.94, respectively (p b 0.001). On a VAS can be interchangeably applied scale of 0 to 10, the 95% limits of for acute pain measurement in adult agreement between the paired NRS patients. and VAS, VAS and CAS, and CAS and NRS ranged from −2.0 to 2.6, from −2.7 to 2.0, and from −2.1 to 2.0, respectively. Using a valid tool for pain assessment (Color-Circle Pain Scale–[CCPS]) had higher scale preference than NRS and gives the clinician an objective criterion for pain management. FPS. Convergent validity was very Due to the subjective nature of pain, good and significant (0.70 –0.75). consideration of socio-cultural factors Inter-rater reliability was high (0.923–0.928) and all the scales were for the particular context ensures that Notes, conclusions Prehospital pain assessment using a VRS and NRS was feasible in this patient population. Further studies are needed to confirm this in other settings. (continued on next page) 712 O. Karcioglu et al. / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (2018) 707–714 Table 1 (continued) Investigator(s), Sample size and population title and date, Ref. # Quality of Risk Objectives evidence of (GRADE)⁎ bias⁎⁎ Göransson KE, et al. 2015. [32]. 217 adult ED patients B L To compare correlations between values on the VAS and the NRS in patients in the ED and to assess the patients' preference of scale Edelen MO, et al. 2010. [33]. 1960 elderly residents from 71 nursing homes B L To compare VDS and NRS using item response theory (IRT) methods to identify the correspondencebetween the scales response options by estimating item parameters for these and five additional pain items. Pratici E, et al. 2017. [34] 97 women in labor C H To determine the level of agreement between calculated percentage pain reduction, derived from VAS or NRS, and patient-reported % pain reduction in patients having epidural analgesia. Gagliese L, et al. 2005. [35] 504 postoperative adults. B L To compare the feasibility and validity of the NRS, VDS, and VAS (horizontal and vertical line orientation) for the assessment of pain intensity in younger and older surgical patients. Bijur PE, et al. 2003. [36] 108 adult ED patients C H Herr K, et al. 2007. [37] 97 adults with chronic joint pain B L To assess the comparability of the NRS and VAS as measures of acute pain, and to identify the minimum clinically significant difference in pain that could be detected on the NRS. To compare the sensitivity and utility of the new IPT with four other pain scales: NRS, VNS, FPS, and VAS, using a naturally occurring pain condition and a controlled treatment with rheumatology patients. Taylor LJ, et al. 2005. [38] 66 cognitively impaired elderly B L To determine the reliability and validity of selected painintensity scales such as the FPS, VDS, NRS, and the Iowa Pain Thermometer (IPT) to assess pain in cognitively impaired older adults. Li L, et al. 2007. 173 [39] postoperative adults. B U To determine the psychometric properties and applicability of four pain scales in Chinese postoperative adults. Li L, et al. 2009. 180 [40] postoperative elderly. B U To evaluate the reliability and validity of the FPS-R, NRS, and the Iowa Pain Thermometer (IPT) for pain assessment in Chinese elders who have had surgery. Findings Notes, conclusions sensitive to change in the intensity or level of pain experienced before and after analgesia. The pain scores generated from the NRS and the VAS were found to strongly correlate (mean difference, 0.41). Most patients found the NRS easier to use than the VAS (61% and 22%, respectively; p b .001). The sample reported moderate amounts of pain on average. Examination of the IRT location parameters for the pain intensity items indicated the following approximate correspondence: VDS mild ≈ NRS 1–4, VDS moderate ≈ NRS 5–7, VDS severe ≈ NRS 8–9, and VDS very severe, horrible ≈ NRS 10. There was moderate agreement between calculated percentage pain reduction from a VAS or NRS and patient-reported % pain reduction in epidural analgesia. The difference could range up to 30%. Psychometric analyses suggested that the NRS was the preferred pain intensity scale. The VDS also had a favourable profile with low error rates and good face, convergent and criterion validity. NRS scores were strongly correlated to VAS scores at all time periods (r = 0.94). The slope of the regression line was 1.01 and the y-intercept was −0.34. The IPT showed the lowest failure rate of all pain scales evaluated. Other scale failure rates were relatively low except for the VNS and the VAS. No significant difference was noted in scale failure by age, gender or education level, but cognitive impairment was significantly related to failure on the VAS and the NRS. Concurrent validity of the VDS, NRS, and IPT was supported with Spearman rank correlation coefficients ranging from .78 to .86 in the cognitively impaired group. The FPS, however, demonstrated weak correlations with other scaleswhen used with the impaired group, ranging from.48 to .53. In the cognitively intact group, strong correlations ranging from.96 to .97 were found among all of thescales. All four pain intensity scales had good reliability and validity when used with Chinese adults. The ICCs of the four scales across current, worst, least, and average pain on each postoperative day were consistently high (0.673-0.825), and all scales at each rating were strongly correlated (r = 0.71–0.99). Both the VDS and the FPS-R had low error rates. Nearly half of the participants (48.1%) preferred the FPS-R, followed by the NRS (24.4%), the VDS (23.1%), and the VAS (4.4%). The intraclass correlation coefficients across current, worst, and least pain on each postoperative day were consistently high (0.949 to 0.965), and all scales at each rating were strongly correlated (r = 0.833 to the appropriate tool is used. A majority reported that the NRS reflected/described their pain better than the VAS (53% and 26%, respectively; p b .01). NRS might be more appropriate to use in the ED Either scale (VDS and NRS) can be used in practice depending on the preference of the clinician and respondent. The concordance correlation coefficient with patient-reported percentage pain reduction was 0.76 and 0.77 for the VAS and NRS, respectively. Difficulties with VAS use among the elderly were identified, including high rates of unscorable data and low face validity The verbally administered NRS can be substituted for the VAS in acute pain measurement. All five pain scales were sensitive in detecting changes in pain intensity pre and post joint injection. All correlations between the scales were strong and significant; however, the intercorrelations for the older cohort were weaker. The scale most preferred in both cohorts of patients was the IPT, followed by the FPS. When asked about scale preference, both the cognitively impaired and the intact groups preferred the IPT and the VDS. This study revealed that cognitive impairment did not inhibit participants' ability to use a variety of pain intensity scales, but the stability issue must be considered. Although all four scales can be options for Chinese adults to report pain intensity, the FPS-R appears to be the best one. No significant differences were noted in terms of gender, age, and educational level. Although all three scales show good reliability, validity, and sensitivity for assessing postoperative pain intensity in Chinese elders, the IPT appears to be a better choice based on patient preference. O. Karcioglu et al. / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (2018) 707–714 713 Table 1 (continued) Investigator(s), Sample size and population title and date, Ref. # Quality of Risk Objectives evidence of (GRADE)⁎ bias⁎⁎ Findings Ismail AK, et al. 133 ambulance 2015. [41] patients B H To evaluate the agreement between verbal NRS and VAS in measuring acute pain in prehospital setting and to identify the preference among paramedics and patients. 35 women with caesarian section C H To evaluate correlation of pain scores obtained on the VAS, the Box Numerical Scale (BNS) and Verbal Rating Scale (VRS) was studied. Akinpelu AO, et al. 2002. [42] Notes, conclusions 0.962). The scale mostly preferred was the IPT (54.7%), followed by the FPS-R (28.5%) and the NRS (15.6%). No significant differences were noted in participant preference by age and cognitive status, but preference for the IPT and the FPS-R were significantly related to gender and education level. VAS performs as well as VNRS in assessing acute pain in prehospital setting. VAS and VNRS must not be used interchangeably to assess acute pain; either method should be used consistently. There was a strong correlation between VNRS and VAS at the scene (r = 0.865; p b 0.001), as well as on arrival at the hospital (r = 0.933; p b 0.001). Kappa values and analysis indicates good agreement between both scales for measuring acute pain. The three pain rating scales measure There was no significant difference the same construct, and could be used between the pain scores obtained on for pain measurement in obstetrically the 3 pain rating scales. Significant related conditions in this correlations existed between pain scores obtained on the VAS and VRS (r environment. = 0.48, p = 0.003); VAS and BNS (r = 0.74, p = 0.000); BNS and VRS (r = 0.74, p = 0.000). Abbreviations: The Faces pain scale (FPS), visual analog scale (VAS), numeric rating scale (NRS), verbal descriptor scale (VDS), thermometer pain scale (TPS), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SFMPQ), and Brief Pain Inventory (BPI). (GRADE system) (GGHO) Grade A: High level of evidence (The true effect lies close to our estimate of the effect.) Grade B: Moderate level of evidence (The true effect is likely to be close to our estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.) Grade C: Low level of evidence (The true effect may be substantially different from our estimate of the effect.) Grade D: Very low level of evidence (Our estimate of the effect is just a guess, and it is very likely that the true effect is substantially different from our estimate of the effect.) ⁎ Quality of evidence and definitions. ⁎⁎ Risk of bias: Studies were assessed for bias using the risk of bias criteria developed by Cochrane [21] which is based upon Cochrane's Risk of Bias Tool [22]. Studies were assessed with regard to selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other sources of bias. Studies were rated as “low risk of bias (L)”, “high risk of bias (H),” or “unclear risk of bias (U)” on a general impression after evaluating all criteria. corresponded, with a few exceptions of systematically higher VAS scores. Limitations of this article are similar to all review articles: the dependence on previously published research and availability of references. There is also a lack of published Level I and Level II studies specific to this topic in the world's literature. 6. Summary and conclusion “Pain cannot be treated if it cannot be assessed”. The most important principle is that clinicians should somehow assess their patients' pain levels, no matter which method or scale one uses to accomplish this task. Special scales developed and validated for patients with difficulties in communication should be made available, and ED physicians should have a plan for assessing pain in different case scenarios. The bulk of evidence published to date have demonstrated a gap for improvement to indicate pluses and minuses of each rating scale used for acute pain. Reports focus that although all pain-rating scales are valid, reliable and appropriate for use in emergency setting, the VAS has somehow appeared more difficult than the others. Elderly patients and those with cognitive impairment, communication problems and minorities have found verbal descriptor or rating scales more practical than others in expression of their pain intensity. Ongoing research in the area of ED patient pain management along with usability of each tool should be conducted on specific patient groups and populations before firm conclusions could be drawn. References [1] Li SF, Greenwald PW, Gennis P, Bijur PE, Gallagher EJ. Effect of age on acute pain perception of astandardized stimulus in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38(6):644–7. [2] Part III: Pain terms, a current list with definitions and notes on usage. In: Merskey H, Bogduk N, editors. Classification of chronic pain. IASP task force on taxonomy, 2nd ed.Seattle: IASP Press; 1994. p. 209–14. [3] Lozner AW, Reisner A, Shear ML, et al. Pain severity is the key to emergency department patients' preferred frequency of pain assessment. Eur J Emerg Med 2010;17(1):30–2. [4] Grant PS. Analgesia delivery in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2006;24(7):806–9. [5] Miner JR, Burton JH. Pain management. In: Walls R, Hockberger R, Gausche-Hill M, editors. Rosen's emergency medicine - concepts and clinical practice. 9th ed. Elsevier Canada; 2018. p. 34–51 (Copyright). [6] Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Acute pain management guideline panel. Clinical practice guidelines. Acute pain management: Operative or medical procedures and traumaRockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1992. [7] Perry S, Heidrich G. Management of pain during debridement: a survey of US burn units. Pain 1982;s13(3):276–80. [8] Kelly AM. The minimum clinically significant difference in visual analogue scale pain score does not differ with severity of pain. Emerg Med J 2001;18(3):205–7. [9] Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S. The measurement of clinical pain intensity: a comparison of six methods. Pain 1986;27:117–26. [10] Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: visual analog scale for pain (VAS pain), numeric rating scale for pain (NRS pain), McGill PainQuestionnaire (MPQ), short-form McGill PainQuestionnaire (SF-MPQ), chronic PainGrade scale (CPGS), short Form-36 bodily pain scale (SF-36 BPS), and measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl. 11):S240–52. [11] Gallagher EJ, Liebman M, Bijur PE. Prospective validation of clinically important changes in painseverity measured on a visual analog scale. Ann Emerg Med 2001; 38(6):633–8. [12] Marco CA, Marco AP. Assessment of pain. In: Thomas SH, editor. Emergency department analgesia: an evidence based guide. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2008. p. 10–8. 714 O. Karcioglu et al. / American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36 (2018) 707–714 [13] McLean SA, Domeier RM, DeVore HK, Hill EM, Maio RF, Frederiksen SM. The feasibility of pain assessment in the prehospital setting. Prehosp Emerg Care 2004;8(2): 155–61. [14] Langley GB, Sheppeard H. The visual analogue scale: its use in pain measurement. Rheumatol Int 1985;5:145–8. [15] von Baeyer CL. Children's self-reports of pain intensity: scale selection, limitations and interpretation. Pain Res Manag 2006;11(3):157–62. [16] Oldenmenger WH, van der Rijt CC. Feasibility of assessing patients' acceptable pain in a randomized controlled trial on a patient pain education program. Palliat Med 2017;31(6):553–8. [17] Goulet JL, Brandt C, Crystal S, Fiellin DA, Gibert C, Gordon AJ, et al. Agreement between electronic medical record-based and self-administered pain numeric rating scale. Med Care 2013;51(3):245–50. [18] Gracely RH, McGrath P, Dubner R. Ratio scales of sensory and affective verbal pain descriptors. Pain 1978;5:5–18. [19] Ferraz MD, Quaresma MR, Aquino LRL, et al. Raliability of pain scales in the assessment of literate and illiterate patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1990;17:1022–4. [20] Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336(7650):924–6. [21] Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). Suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews. EPOC resources for review authors. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services; 2016. [22] Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from: http://www.handbook.cochrane.org/; 2011. [23] Leigheb M, Sabbatini M, Baldrighi M, Hasenboehler EA, Briacca L, Grassi F, et al. Prospective analysis of pain and pain management in an emergency department. Acta Biomed 2017;88(4-S):19–30. [24] Pereira LV, Pereira Gde A, Moura LA, Fernandes RR. Pain intensity among institutionalized elderly: a comparison between numerical scales and verbal descriptors. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2015;49(5):804–10. [25] Herr KA, Spratt K, Mobily PR, Richardson G. Painintensity assessment in older adults: use of experimental pain to compare psychometric properties and usability of selected pain scales with younger adults. Clin J Pain 2004;20(4):207–19. [26] Ware LJ, Epps CD, Herr K, Packard A. Evaluation of the revised Faces pain scale, verbal descriptor scale, numeric rating scale, and Iowa pain thermometer in older minority adults. Pain Manag Nurs 2006;7(3):117–25. [27] Yazici Sayin Y, Akyolcu N. Comparison of pain scale preferences and pain intensity according to pain scales among Turkish patients: a descriptive study. Pain Manag Nurs 2014;15(1):156–64. [28] Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs 2005;14(7):798–804. View publication stats [29] Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, et al. European palliative care research collaborative (EPCRC). Studies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41(6):1073–93. [30] Bahreini M, Jalili M, Moradi-Lakeh MA. Comparison of three self-report pain scales in adults with acute pain. J Emerg Med 2015;48(1):10–8. [31] Aziato L, Dedey F, Marfo K, Asamani JA, Clegg-Lamptey JN. Validation of three pain scales among adult postoperative patients in Ghana. BMC Nurs 2015;14:42. [32] Göransson KE, Heilborn U, Selberg J, von Scheele S, Djärv T. Pain rating in the ED—a comparison between 2 scales in a Swedish hospital. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33(3): 419–22. [33] Edelen MO, Saliba D. Correspondence of verbal descriptor and numeric rating scales for pain intensity: an item response theory calibration. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010;65(7):778–85. [34] Pratici E, Nebout S, Merbai N, Filippova J, Hajage D, Keita H. An observational study of agreement between percentage pain reduction calculated from visual analog or numerical rating scales versus that reported by parturients during labor epidural analgesia. Int J Obstet Anesth 2017;30:39–43. [35] Gagliese L, Weizblit N, Ellis W, Chan VW. The measurement of postoperative pain: a comparison of intensity scales in younger and older surgical patients. Pain 2005; 117(3):412–20. [36] Bijur PE, Latimer CT, Gallagher EJ. Validation of a verbally administered numerical ratingscale of acute pain for use in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2003;10(4):390–2. [37] Herr K, Spratt KF, Garand L, Li L. Evaluation of the Iowa pain thermometer and other selected pain intensity scales in younger and older adult cohorts using controlled clinical pain: a preliminary study. Pain Med 2007;8(7):585–600. [38] Taylor LJ, Harris J, Epps CD, Herr K. Psychometric evaluation of selected pain intensity scales for use with cognitively impaired and cognitively intact older adults. Rehabil Nurs 2005;30(2):55–61. [39] Li L, Liu X, Herr K. Postoperative pain intensity assessment: a comparison of four scales in Chinese adults. Pain Med 2007;8(3):223–34. [40] Li L, Herr K, Chen P. Postoperative pain assessment with three intensity scales in Chinese elders. J Nurs Scholarsh 2009;41(3):241–9. [41] Ismail AK, Abdul Ghafar MA, Shamsuddin NS, Roslan NA, Kaharuddin H, Nik Muhamad NA. The assessment of acute pain in pre-hospital care using verbal numerical rating and visual analogue scales. J Emerg Med 2015;49(3):287–93. [42] Akinpelu AO, Olowe OO. Correlative study of 3 pain rating scales among obstetric patients. Afr J Med Med Sci 2002;31(2):123–6.