ЕС Трансформация. Элли Лука. Перевод Должикова

реклама

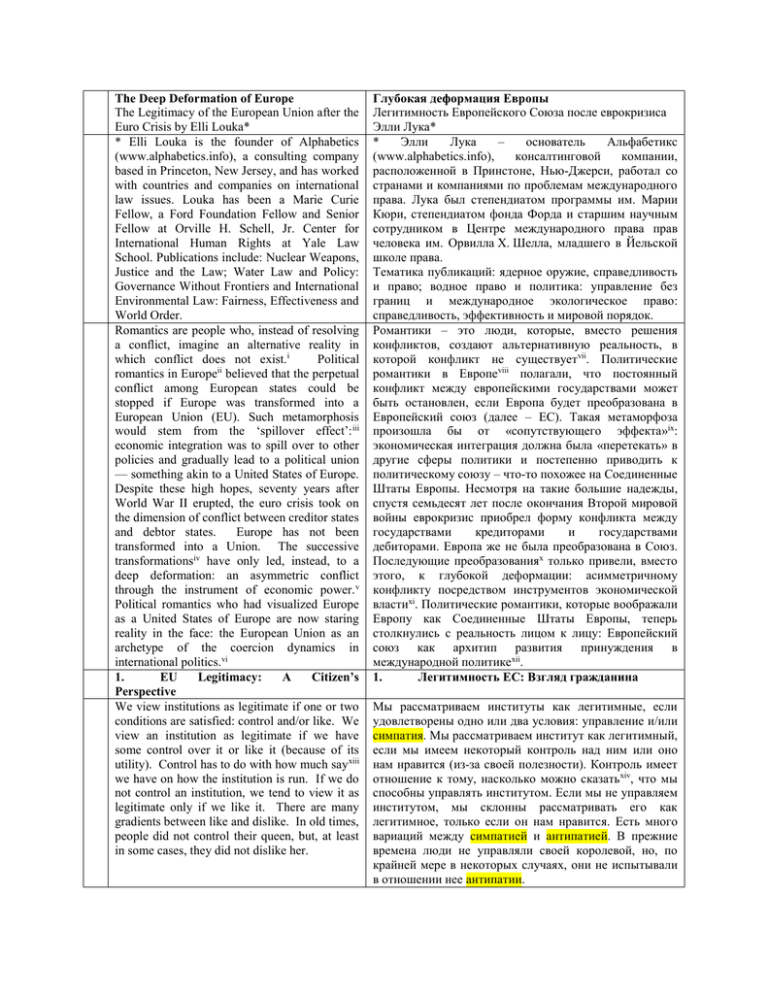

The Deep Deformation of Europe The Legitimacy of the European Union after the Euro Crisis by Elli Louka* * Elli Louka is the founder of Alphabetics (www.alphabetics.info), a consulting company based in Princeton, New Jersey, and has worked with countries and companies on international law issues. Louka has been a Marie Curie Fellow, a Ford Foundation Fellow and Senior Fellow at Orville H. Schell, Jr. Center for International Human Rights at Yale Law School. Publications include: Nuclear Weapons, Justice and the Law; Water Law and Policy: Governance Without Frontiers and International Environmental Law: Fairness, Effectiveness and World Order. Romantics are people who, instead of resolving a conflict, imagine an alternative reality in which conflict does not exist.i Political romantics in Europeii believed that the perpetual conflict among European states could be stopped if Europe was transformed into a European Union (EU). Such metamorphosis would stem from the ‘spillover effect’: iii economic integration was to spill over to other policies and gradually lead to a political union — something akin to a United States of Europe. Despite these high hopes, seventy years after World War II erupted, the euro crisis took on the dimension of conflict between creditor states and debtor states. Europe has not been transformed into a Union. The successive transformationsiv have only led, instead, to a deep deformation: an asymmetric conflict through the instrument of economic power. v Political romantics who had visualized Europe as a United States of Europe are now staring reality in the face: the European Union as an archetype of the coercion dynamics in international politics.vi 1. EU Legitimacy: A Citizen’s Perspective We view institutions as legitimate if one or two conditions are satisfied: control and/or like. We view an institution as legitimate if we have some control over it or like it (because of its utility). Control has to do with how much say xiii we have on how the institution is run. If we do not control an institution, we tend to view it as legitimate only if we like it. There are many gradients between like and dislike. In old times, people did not control their queen, but, at least in some cases, they did not dislike her. Глубокая деформация Европы Легитимность Европейского Союза после еврокризиса Элли Лука* * Элли Лука – основатель Альфабетикс (www.alphabetics.info), консалтинговой компании, расположенной в Принстоне, Нью-Джерси, работал со странами и компаниями по проблемам международного права. Лука был степендиатом программы им. Марии Кюри, степендиатом фонда Форда и старшим научным сотрудником в Центре международного права прав человека им. Орвилла Х. Шелла, младшего в Йельской школе права. Тематика публикаций: ядерное оружие, справедливость и право; водное право и политика: управление без границ и международное экологическое право: справедливость, эффективность и мировой порядок. Романтики – это люди, которые, вместо решения конфликтов, создают альтернативную реальность, в которой конфликт не существуетvii. Политические романтики в Европеviii полагали, что постоянный конфликт между европейскими государствами может быть остановлен, если Европа будет преобразована в Европейский союз (далее – ЕС). Такая метаморфоза произошла бы от «сопутствующего эффекта»ix: экономическая интеграция должна была «перетекать» в другие сферы политики и постепенно приводить к политическому союзу – что-то похожее на Соединенные Штаты Европы. Несмотря на такие большие надежды, спустя семьдесят лет после окончания Второй мировой войны еврокризис приобрел форму конфликта между государствами кредиторами и государствами дебиторами. Европа же не была преобразована в Союз. Последующие преобразованияx только привели, вместо этого, к глубокой деформации: асимметричному конфликту посредством инструментов экономической властиxi. Политические романтики, которые воображали Европу как Соединенные Штаты Европы, теперь столкнулись с реальность лицом к лицу: Европейский союз как архитип развития принуждения в международной политикеxii. 1. Легитимность ЕС: Взгляд гражданина Мы рассматриваем институты как легитимные, если удовлетворены одно или два условия: управление и/или симпатия. Мы рассматриваем институт как легитимный, если мы имеем некоторый контроль над ним или оно нам нравится (из-за своей полезности). Контроль имеет отношение к тому, насколько можно сказатьxiv, что мы способны управлять институтом. Если мы не управляем институтом, мы склонны рассматривать его как легитимное, только если он нам нравится. Есть много вариаций между симпатией и антипатией. В прежние времена люди не управляли своей королевой, но, по крайней мере в некоторых случаях, они не испытывали в отношении нее антипатии. Рис. 1 Легитимность институтов Figure 1: Legitimacy of Institutions Control Western Democracy (legitimate) Club (legitimate) Like Bad Queen (illegitimate) Good Queen (legitimate) Figure 1 depicts the legitimacy of institutions based on the two variables of ‘control’ and ‘like’ and gives examples of institutions expressing legitimate/illegitimate options. When we control and like an institution that institution enjoys a high level of legitimacy. In those cases, the institution is more like a club where we socialize with like-minded equals. When we control an institution, but we dislike it, the institution can enjoy legitimacy because we still have control over it and we perceive that we can possibly change it to our liking. However, there are cases that even if we have control over an institution, we cannot change it significantly either because there is not enough consensus for change or because a consensus exists that the institution is the best of all possible worlds. Today, some people feel this way about Western representative democracy. Some do not like representative democracy and prefer more direct democratic models that make possible active citizen participation in political affairs.xv At the same time, most agree that, due to increasing populations and unenviable alternatives, representative democracy with some tweaks is the optimum. When we dislike an institution but maintain some control over it, we have two options: to exit or to exercise our control to try to change the institution to our liking. A minimum amount of control can be exercised through dialogue and voting or even loud protests and threats.xvi In Western democratic states, exit is rarely contemplated by the citizenry as it leads to forfeiting significant rights and benefits. In principle, however, citizens are not afraid to exercise control by voting governments out of power, protesting and striking. When we do not control an institution and we Контроль Западная Клуб демократия (легитимный) (легитимная) Плохая Хорошая королева королева (нелегитимная) (легитимная) Симпатия Рисунок 1 изображает легитимность институтов, основанных на двух переменных «контроля» и «симпатии», и дает примеры институтов, выражающих легитимные/нелегитимные варианты. Когда мы управляем и нам нравится институт, этот институт характеризуется высоким уровнем легитимности. В таких случаях институт больше походит на клуб, где мы общаемся с единомышленниками. Когда мы управляем институтом, но нам он не нравится, институт может характеризоваться легитимностью, поскольку мы все еще управляем им, и мы чувствуем, что возможно можем изменить его в сторону нашей симпатии. Однако, есть случаи, когда, даже если мы управляем институтом, мы его не можем существенно изменить либо поскольку недостаточно согласия для таких перемен либо поскольку существует согласие в том, что данный институт является лучшим из всех возможных в мире. Сегодня, некоторые люди испытывают подобные чувства в отношении западной представительной демократии. Некоторые не любят представительную демократию и предпочитают более модели непосредственной демократии, которые обеспечивают возможное активное участие гражданина в политических делахxvii. В то же самое время большинство соглашается с тем, что, вследствие роста населения и иных нежелательных перспектив, представительная демократия с некоторыми корректирповками является оптимальной моделью. Когда институт нам не нравится, но гарантирован некоторый контроль над ним, у нас есть два варианта: покинуть его или осуществлять наш контроль с тем, чтобы попытаться изменить институт в соответствии с нашими представлениями, как если бы он нам нравился. Минимальный объем контроля может быть осуществлен через диалог и голосование или даже активные протесты и угрозыxviii. В западных демократических государствах первый вариант редко рассматривается населением, поскольку это приводит к утрате фундаментальных прав и благ. В принципе, однако, граждане не боятся осуществлять контроль, отказывая органам власти в поддержке на выборах, используя протест и забастовки. Когда мы не управляем институтом, и он нам не dislike it, an obvious case being that of a bad queen, the institution is illegitimate. We cannot leave without risking serious repercussions and we cannot voice our dissatisfaction. Revolution, with the ensuing social chaos, is available when the situation becomes unbearable. Finally, there are institutions that we like but we cannot control. An example is that of a good queen, who uses her power for the benefit of her constituents. These are the queens who are effective at bringing peace and prosperity and they are liked even if they lack democratic credentials. The legitimacy of the European Union, like that of a good queen, was not based on its democratic credentials. On the contrary, Europeans liked the EU because it was useful to them. The EU was effective at bringing peace and prosperity in a divided continent that had suffered many wars. Greece joined the European Union shortly after it restored democracy, as it saw in the EU membership the bulwark against foreign-engineered dictatorship. Eastern European countries joined the Union to shield themselves against Russian imperialism. Most Europeans accepted the euro because it seemed to bring clear benefits or, at least, do no harm. Once things started to go wrong Europeans started to protest. Only their protests had the wrong audience. They could throw out their governments (and they did so)xix based on the democratic principles of the nation state, but they could not disband European institutions or sack the governments of other eurozone countries. Yet it was the European institutions and creditor states that dictated the economic conditions in the periphery. Vis-à-vis these core Eurozone governments, the citizens of the periphery were disenfranchised. Because of the coercive relationship between creditors and debtors, the EU has been deformed into an illegitimate establishment. Europeans had willy-nilly convinced themselves that their delegation of powers to the European Union, through their national government, was enough to satisfy their appetite for democracy in the Union. Now that they are confronted by an entity they neither control nor like, they regret the surrender of control. The discontent is palpable in debtor countries. In creditor countries also, despite the fact that they have won,xxi there is backlash against the ‘reckless нравится институт является нелегитимнымым. Очевидным примером этого является случай (модель) плохой королевы. Мы не можем покинуть институт, не рискуя серьезными последствиями, и мы не можем высказать нашу неудовлетворенность. Революция, с последующим социальным хаосом, доступна, когда ситуация становится невыносимой. Наконец, есть институты, которые нам нравятся, но мы их не можем контролировать. Примером является – случай (модель) хорошей королевы, которая использует свою власть в пользу своих подданых. Существуют королевы, которые эффективны в поддержании мира и процветания, и они нравятся подданым, даже если они испытывают недостаток демократического мандата доверия. Легитимность Европейского Союза, как у такой хорошей королевы, не была основана на его демократическом мандате доверия. Напротив, европейцам понравился ЕС, потому что он был полезен для них. ЕС был эффективен в поддержании мира и процветания на разделенном континенте, который испытывал негативные последствия нескольких войн. Греция присоединилась к Европейскому Союзу вскоре после того, как она восстановила демократию, поскольку рассматривала членство в Европейском Союзе в качестве оплота против иностранно спроектированной диктатуры. Восточноевропейские страны вступали в Союз, чтобы оградить себя от российского империализма. Большинство европейцев приняло Евро, поскольку казалось, что оно приносит им ясную выгоду или, по крайней мере, не причиняет вреда. Как только дела стали идти плохо, европейцы начали протестовать. Только у этих протестов была неправильная аудитория. Они могли не поддержать на выборах свои правительства (и они так сделали) xx, основываясь на демократических принципах национального государства, но они не могли распустить европейские институты или отправить в отставку правительства других стран Еврозоны. К тому времени это были европейские институты и государства кредиторы, которые диктовали экономические условия на периферии. В отличии от этих государств, находящихся в центре Еврозоны, на периферии граждане были лишены своих основных прав. Из-за того, что отношения между кредиторами и дебиторами были основаны на принуждении, ЕС превратился в нелегитимный институт. Европейцы сами волей-неволей пришли к убеждению, что передача полномочий Европейскому Союзу через собственные национальные правительства, была достаточным, чтобы удовлетворить свой аппетит к демократии в Союзе. В тот момент как они столкнулись с учреждением, которое ими ни управлялось и не нравилось, они пожалели об утрате контроля над ним. Недовольство наиболее ощутимо в странах дебиторах. В странах же кредиторах, несмотря даже на их победу, также есть негативная реакция на «беспечную периферию»xxiii и periphery’ and intra-European migration.xxii 2. EU Legitimacy: Creditor States versus Debtor States An institution is unlikely to listen to those who cannot convincingly articulate a threat of countermeasures if their voices are not heard. During the euro crisis when Europe-periphery was voicing dissatisfaction, it did not have any threats at its disposal to make that dissatisfaction heard in the circles of Europecore. The relationship between creditors and debtors is a power-relationship —by definition asymmetrical as creditors have the upper hand. The peripheral/debtor states have invested their financial and political future in the euro membership and the penalties for exiting the euro are tremendous. In organizations where entry is expensive or requires severe initiation, like the eurozone, threats of exit sound hollow. xxv If exit is accompanied by further sanctions, such as financial isolation, the very idea of exit is unthinkable. Organizations that deprive their members of both exit and voice are like dictators or the bad queen. Exit from such organizations, if ever attempted, is equivalent to suicide-bombing. Monetary policy is a public good because it regulates the economic breathing space for citizens and states. Today the global monetary policy is set by the United States Federal Reserve, which prints the reserve currency of the world. States that challenge the United States monetary supremacy must find some way to exist in a self-sufficient manner running their own economy isolated from the world.xxvii Not many states can achieve that. Today Germany is an informal empire because nothing really can be accomplished in Europe without its consent and the periphery states have become third world countries indebted in a currency they do not control. States of the European South have no control over the currency and the printing press the way emerging states do not have such control when they issue debt denominated in a foreign currency.xxviii Moreover, the loss of sovereignty over monetary policy has led to the loss of sovereignty over fiscal policy. The PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italty, Greece, Spain) are now the exemplification of the periphery but they do not have the advantages of the classic periphery: they cannot devalue their currency, they cannot impose capital controls — unless they are told to do so — they do not control fiscal policy. внутриевропейскую миграциюxxiv. 2. Легитимность ЕС: государства кредиторы против государств дебиторов Институт вряд ли будет воспринимать тех, кто не может убедительно и ясно сформулировать опасность ответных мер, если их голоса не слушают. Во время европейского кризиса, когда европейская периферия высказывала неудовлетворенность, у нее не было в распоряжении никаких средств, чтобы сделать ту неудовлетворенность услышанной в европейском центре. Отношения между кредиторами и дебиторами – это отношения власти-подчинения и по определению асимметричные ведь у кредиторов есть возможность взять верх. Периферийные государства / государствадебиторы инвестировали свое финансовое и политическое будущее в европейское членство, и наказание за выход из зоны евро громадное. В организациях подобной еврозоне, где членство является дорогим или предполагает сложный обряд посвящения, угрозы выхода становятся пустымиxxvi. Если выход сопровождается дальнейшими санкциями, такими как финансовая изоляция, самая идея выхода является невероятной. Организации, которые лишают своих членов права выхода и голоса напоминают диктаторов или плохую королеву. Выход из таких организаций, если только когда-либо предпринимается, равноценен террористическому акту. Валютная политика выступает общественным благом, поскольку она регулирует экономическую передышку для граждан и государств. Сегодня глобальная валютная политика установлена Федеральной резервной системой США, которая печатает мировую резервную валюту. Государства, которые бросают вызов денежному превосходству Соединенных Штатов, должны найти некий способ существования в самодостаточной манере, управляя своей собственной экономикой в изоляции от мираxxix. Не многие государств могут этого достичь. Сегодняшняя Германия является неофициальной империей, поскольку в действительности ничего не может свершится в Европе без ее согласия и периферийные государства стали странами третьего мира, задолжавшие в валюте, которая им неподкотрольна. Государства европейского Юга не имеют никакого контроля над валютой и печатным станком также как развивающиеся государства не имеют такого контроля, если они выпускают долговые обязательства в иностранной валютеxxx. Более того, утрата суверенитета над монетарной политикой привела к утрате суверенитета над фискальной политикой. Страны ПИИГИ [PIIGS] (Португалия, Ирландия, Италия, Греция, Испания) являются в настоящее время иллюстративным примером периферии, но у них нет преимуществ классической периферии: они не могут девальвировать свою валюту, они не могут располагать контролем над капиталами (до тех пор, им не скажут сделать этого), они не управляют фискальной In the eurozone, the ECB, in which the German Central Bank holds an effective veto, dictates monetary conditions. The rest of the states can keep nagging or exit at their peril. Certainly constant nagging can irk some officials, but it is not effective voice. Core states knew well that the debt and deficits of the periphery were not the cause of the crisis. Europe-core was willing to overlook these problems of the periphery before the crisis because supposedly the political priority of European Unity was more important than economic disparities. When the crisis erupted, Germany understood quite well that the repayment of debt could not be guaranteed given the condition of the periphery. It insisted, however, on unmitigated conditionality in the midst of a recession as it pursued single-mindedly the export of its economic policies.xxxi It has been said that if one strikes us on the right cheek, we must turn to offer her the left. Today the name of the game is to stop the first strike preemptively, by blowing off the hand that is about to inflict it.xxxiii If that is not feasible, one must be able to effectively administer a second strike. Certainly we must not convince ourselves that we are in a Union with states that are relentless at inflicting strikes. The primordial understanding of ‘who’s the enemy’xxxiv is the cornerstone for the survival of states. When an economic war is taking place, sovereign is the state that can insulate itself as much as possible from economic crises. xxxv By surrendering monetary sovereignty, the peripheral states have deprived themselves of the little independence they had. Now the citizens of these states are at the mercy of the governments of other states. These governments, by definition, cannot be enamored with the well-being of citizens who do not vote for them. Assuming that exit is excluded as an option, the European Union is faced with the following choice: (1) Political union; or (2) an abiding German hegemony. Only a real political union (like that of the United States or Switzerland) would make it unnecessary for a single member state to remain a hegemon. For Germany and many other states the idea of a real political union is the founding myth of the European Union. It is a distant myth that has absolutely no bearing on the experienced reality. политикой. В еврозоне Европейский центральный банк (EЦБ), в котором Немецкий федеральный банк имеет эффективное вето, диктует монетарную политику. Остальные государства могут продложать «ворчать» или выйти на свой собственный риск. Конечно, постоянное «ворчание» может раздражать некоторых чиновников, но это не эффективный способ выражения мнения. Государства, относящиеся к центру, хорошо знали, что долг и дефицит на периферии не был причиной кризиса. Европейский центр желал не обращать внимания на эти проблемы периферии перед кризисом, поскольку предположительно политические приоритеты европейского единства были более важными чем экономические диспропорции. Когда кризис разразился, Германия вполне хорошо поняла, что уплата долга не может быть гарантирована, учитывая положение периферии. Однако она настояла на абсолютной обусловленности в середине рецессии, поскольку она добивалась целенаправленного экспорта принципов своей экономической политикиxxxii. Как говорится, если вас ударили по правой щеке, мы должны повернуться, подставив левую. Сегодня название игры является: упреждающее останови первый удар, отбивая руку, которая собирается его нанестиxxxvi. Если это не сделано, нужно быть в состоянии эффективно нанести второй удар. Конечно, мы не должны убеждать себя, что мы состоим в Союзе с государствами, которые являются безжалостными в нанесении ударов. Исконное понимание того, «кто враг»xxxvii является краеугольным камнем для выживания государств. Когда имеет место экономическая война, сувереном является государство, которое может изолировать себя в максимально возможной степени от экономических кризисов xxxviii. Сдавая моетарный суверенитет, периферийные государства сами лишили себя той маленькой независимости, которую они имели. Теперь граждане этих государств находятся во власти правительств других государств. Эти же правительства, по определению, не могут быть заинтересованы в благосостоянии граждан, которые не голосуют за них. Резюмируя, что выход как опция исключен, Европейский Союз сталкивается со следующим выбором: (1) Политический союз; или (2) неизменная немецкая гегемония. Только реальный политический союз (как в Соединенных Штатах или в Швейцарии) сделал бы ненужным одному государству-члену остаться гегемоном. Для Германии и многих других государств идея реального политического союза является мифом при создании Европейского Союза. Он является мифом совершенно далеким от реальной действительности. The European identity is a pretend identity. Europeans endorsed this manufactured identity, believing that it would grant them powers they have never had before. The idea of the European Union was based on the equality of sovereign member states that emerged equally scarred from many wars. xxxix As these states grew and diverged in policies and growth paths, the European identity kept them together, even if clearly some of them grew more powerful and more prosperous than others did. After the euro crisis turned into economic conflict,xl which divided Europe into creditor states and debtor states, the European identity has crumbled. The trumpeted equality of member states, the foundation of European integration, has been unmasked as a sham. The EU can punish weak states, like Greece and Cyprus, but it is powerless against the dominant member states that define the rules and the exceptions to the rules — the real sovereigns.xli The periphery, as a result, has been grabbed by old fashioned nationalists who believe they have a duty to defend it.xlii Good luck — they need it. The Leviathanxliii is being ‘Made in Germany.’ Европейская идентичность представляет собой мнимую идентичность. Европейцы одобрили эту искусственную идентичность, полагая, что она предоставит им власть, которую они никогда прежде не имели. Идея Европейского Союза была основана на равенстве суверенных государств-членов, которые появились одинаково травмированными от многих войнxliv. Поскольку эти государства росли и расходились в направлениях политики и путях роста, европейская идентичность держала их вместе, даже если некоторые из них очевидно становились более сильными и более богатыми, чем другие. После того, как европейский кризис превратился в экономический конфликт xlv, который разделил Европу на государства кредиторы и государства дебиторы, европейская идентичность разрушилась. Провозглашаемое равенство государствчленов, как основание европейской интеграции, было разоблачено как обман. ЕС может наказать слабые государства такие как Греция и Кипр, но он бессилен против доминирующих государств-членов, которые определяют правила и исключения из них, – настоящих сувереновxlvi. В результате периферия была захвачена старомодными националистами, которые верят в наличие у них обязательства защитить ееxlvii. Удачи – они в этом нуждаются. Левиафанxlviii – «Сделано в Германии». * Elli Louka is the founder of Alphabetics (www.alphabetics.info), a consulting company based in Princeton, New Jersey, and has worked with countries and companies on international law issues. Louka has been a Marie Curie Fellow, a Ford Foundation Fellow and Senior Fellow at Orville H. Schell, Jr. Center for International Human Rights at Yale Law School. Publications include: Nuclear Weapons, Justice and the Law; Water Law and Policy: Governance Without Frontiers and International Environmental Law: Fairness, Effectiveness and World Order. i See Carl Schmitt, Political Romanticism (translation Guy Oakes, 1986). ii See, e.g., Elli Louka: Water Law and Policy: Governance Without Frontiers (2008) (analyzing how water policy has been oriented towards building a Europe without frontiers). iii See Elli Louka, Conflicting Integration:the Environmental Law of the European Union 5 (2004). iv See Treaty Establishing the European Economic Community (EEC Treaty or Treaty of Rome), Mar. 25, 1957, reprinted in 298 U.T.S. 3. The EEC Treaty was followed by the Single European Act, Feb. 17, 1986; the Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty), Feb. 7, 1992; the Treaty of Amsterdam, Oct. 2, 1997; the Treaty of Nice, Feb. 26, 2001; the Treaty of Lisbon, Dec. 13, 2007. These treaties have been consolidated. See Consolidated Versions of the Treaty on European Union (EU Treaty) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), OJ C 326/1, 26.10.2012. v On the coercive use of economic power, see Myres S. McDougal, The Impact of International Law upon National Law: A Policy-Oriented Perspective, 4 South Dakota Law Review 25, at 47-48 (1959). vi See, e.g., W. Michael Reisman, Coercion and Self-Determination: Construing Article 2(4), 78 American Journal of International Law 642 (1984). vii См.: Schmitt, C. Political Romanticism / translation Guy Oakes. 1986. viii См. напр.: Louka, E. Water Law and Policy: Governance Without Frontiers. 2008. (проводится анализ того, как политика в области водных ресурсов направлена на формирования Европы без границ. ix See Elli Louka, Conflicting Integration:the Environmental Law of the European Union 5 (2004). x См.: Договор об учреждении Европейского экономического сообщества от 25 марта 1957 г. (далее – Договор о ЕЭС или Римский договор) // Договоры, учреждающие Европейские Сообщества. – М.: Право, 1994. – С. 95–288; U.T.S. 1957. Vol. 298. P. 3. За договором о ЕЭС следовали Единый Европейский акт от 17 февраля 1986 г.; Договор о Европейском Союзе от 7 февраля 1992 г. (Маастрихтский договор) // Единый европейский акт. Договор о Европейском союзе. – М.: Право, 1994. – С. 45 – 246; Амстердамский договор от 2 октября 1997 г.; Ницкий договор от 26 февраля 2001 г.; Лисабонский договор от 13 декабря 2007 г. Все эти договоры были консолидированы. См.: Консолидированные версии Договора о Европейском Союзе (Договор о ЕС) и Договора о функционировании Европейского Союза (ДоФЕС) // Official Journal. 2012. C 326/1. P. . xi О принудительном использовании экономической власти см.: McDougal, M. S. The Impact of International Law upon National Law: A Policy-Oriented Perspective // South Dakota Law Review. 1959. Vol. 4. P. 25, 47–48. xii См.: например: Reisman, W. M. Coercion and Self-Determination: Construing Article 2(4) // American Journal of International Law. 1984. Vol. 78. P. 642. xiii See Albert O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations and States 4-5 (1970). xiv См.: Hirschman, A.O. Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations and States. 1970. P. 4–5. xv See Elli Louka, Water Law and Policy: Governance Without Frontiers 205-43 (2008) (analyzing models of participatory democracy). xvi See, e.g., Hirschman, supra note 7, at 66. xvii См.: Louka, E. Water Law and Policy: Governance Without Frontiers 2008. P. 205-243. (в работе анализируются модели демократии участия [participatory democracy]). xviii См. например: Hirschman, A.O. Op. cit. P. 66. xix See Lawrence LeDuc et al., The Electoral Impact of the 2008 Economic Crisis in Europe 87, in Economic Crisis in Europe: What It Means for the EU and Russia (Joan DeBardeleben et al., eds., 2013). xx См.: LeDuc, L. et al., The Electoral Impact of the 2008 Economic Crisis in Europe // Economic Crisis in Europe: What It Means for the EU and Russia / eds. J. DeBardeleben et al. 2013. P. 87. xxi 'Now Europe Is Speaking German:' Merkel Ally Demands that Britain 'Contribute' to EU Success, Spiegel, Nov. 15, 2011 available online http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/now-europe-is-speaking-german-merkel-allydemands-that-britain-contribute-to-eu-success-a-798009.html. xxii See Anna Myunghee Kim , Foreign Labour Migration and the Economic Crisis in the EU: Ongoing and Remaining Issues of the Migrant Workforce in Germany, IZA Discussion Paper No. 5134, Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit (Institute for the Study of Labor) (2010). xxiii «Now Europe Is Speaking German»: Merkel Ally Demands that Britain «Contribute» to EU Success // Spiegel. 2011. 15 of November. URL: http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/now-europe-is-speaking-german-merkelally-demands-that-britain-contribute-to-eu-success-a-798009.html (дата обращения: 01.12.2014) xxiv См.: Kim, A.M. Foreign Labour Migration and the Economic Crisis in the EU: Ongoing and Remaining Issues of the Migrant Workforce in Germany // Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit (IZA) Discussion Paper. 2010. № 5134. xxv Hirschman, supra note 7, at 96. xxvi Hirschman, A.O. Op. cit. P. 96. xxvii For example, Iran, Syria, North Korea. See Elli Louka, Nuclear Weapons, Justice and the Law (2011) (on the economic isolation of states that are allegedly manufacturing nuclear weapons and are not the internationally recognized nuclear powers). xxviii Paul De Grauwe, Governance of a Fragile Eurozone, at 3, CEPS Working Document, No. 346, Centre for European Policy Studies, 2011. See also Barry Eichengreen et al., The Pain of Original Sin 13, in Other People’s Money: Debt Denomination and Financial Instability in Emerging Market Economies (Barry Eichengreen et al., eds. 2005). xxix Например, Иран, Сирия, Северная Корея. См.: Louka, E. Nuclear Weapons, Justice and the Law. Cheltenham; Northampton: Edward Elgar, 2011. (об экономической изоляции государств, которые предположительно производят ядерные вооружения и не являются международно-признанными ядерными державами). xxx Grauwe, P. De Governance of a Fragile Eurozone // Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) Working Document. 2011. № 346. P. 3. См. также: Eichengreen, B. The Pain of Original Sin 13 / B. Eichengreen, R. Hausmann, U. Panizza // Other People’s Money: Debt Denomination and Financial Instability in Emerging Market Economies / eds. B. Eichengreen, R. Hausmann. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. xxxi See generally Sebastian Dullien et al., The Long Shadow of Ordoliberalism: Germany’s Approach to the Euro Crisis, European Council of Foreign Relations Policy Brief No. 49 (2012). xxxii См. в общем: Dullien, S. The Long Shadow of Ordoliberalism: Germany’s Approach to the Euro Crisis / S. Dullien, U. Guérot // European Council of Foreign Relations Policy Brief. 2012. № 49. xxxiii See Elli Louka, Precautionary Self-Defense and the Future of Preemption in International Law 951, in Looking to the Future: Essays on International Law in Honor of W. Michael Reisman (M. H. Arsanjani et al., eds., 2011). xxxiv See generally Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political 26 (foreword by Tracy B. Strong, 2007). xxxv States that have had the most successful ammunition against economic crises include Switzerland and China. xxxvi См.: Louka, E. Precautionary Self-Defense and the Future of Preemption in International Law // Looking to the Future: Essays on International Law in Honor of W. Michael Reisman / eds. M. H. Arsanjani. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2011. P. 951. xxxvii См. в общем: Schmitt, C. The Concept of the Political. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. P. 26. xxxviii Государствами, которые которые имеют наиболее успешные средства защиты от экономических кризисов, являются Швейцария и Китай. xxxix See, e.g., Henri Cartier-Bresson, Europeans (1955). xl This type of economic conflict is not new. Before World War II, the League of Nations emphasized the importance of economic disarmament. See Herbert Samuel, The World Economic Conference, 12 International Affairs 439 (1933). For the economic foreign policy of the United States before World War II, see Jeff Frieden, Sectoral Conflict and Foreign Economic Policy 1914-1940, 42 International Organization 59 (1988). xli See Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty 5-6 (translation George Schwab, 1985). See also Bodin, On Sovereignty 1 (defining sovereignty as the ‘absolute and perpetual power,’ what the Greeks call akra exousia) (Julian H. Franklin ed., 1992). According to Bodin, the sovereign can never become the underdog. The sovereign ‘cannot tie his hands even if he wished to do so.’ See id. at 13. xlii See Timothy Garton Ash, 2014 is not 1914, but Europe is Getting Increasingly Angry and Nationalist, Guardian, Nov.17, 2013. xliii Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Common Wealth Ecclesiastical and Civil 25161 (C.B. Macpherson, ed., 1971) (analyzing the commonwealth by acquisition). xliv См. например: Cartier-Bresson, H. Europeans: photographs [taken from 1950 to 1955]. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1955. xlv Такой тип экономического конфликта не является новым. Перед второй мировой войной, в Лиге Наций обращалось внимание на важность экономического разоружения. См.: Samuel, H. The World Economic Conference // International Affairs. 1933. Vol. 439. P. 12. О внешней экономической политики США перед второй мировой войной см.: Frieden, J. Sectoral Conflict and Foreign Economic Policy 1914-1940 // International Organization. 1988. Vol. 59. P. 42. xlvi См.: Schmitt, C. Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985. P. 5–6. См. также: Bodin, J. On Sovereignty: four chapters from the six books of the commonwealth. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992. P. 1. (определяющий суверенитет как «абсолютную и постоянную власть», которую греки называли akra exousia). Согласно Ж. Бодену, суверен никогда не может быть аутсайдером. Суверен «не может связать свои руки даже если он хочет это сделать». См.: Ibid. P. 13. xlvii См.: Ash, T. G. 2014 is not 1914, but Europe is Getting Increasingly Angry and Nationalist // Guardian. 2013. 17 of November. xlviii Hobbes, Th. Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a CommonWealth Ecclesiastical and Civil. Harmondsworth: Penguin books, 1971. P. 251–261. (анализирующий государство как приобретение).