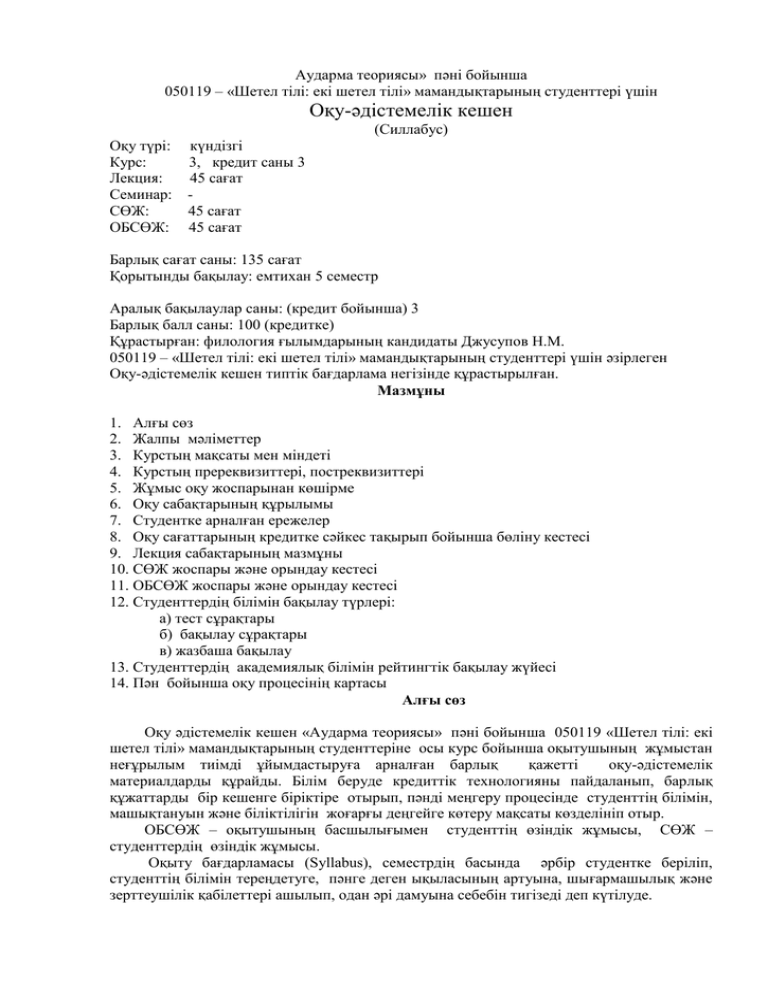

Аударма теориясы» пәні бойынша

advertisement