Шок

advertisement

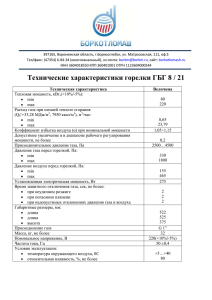

Шок Е.В. Григорьев Лаборатория критических состояний НИИ КПССЗ СО РАМН, кафедра анестезиологии и реаниматологии КемГМА, г. Кемерово New Concepts in the Diagnosis and Fluid Treatment of Circulatory Shock Thirteenth Annual Becton, Dickinson and Company Oscar Schwidetsky Memorial Lecture Max H. Weil, MD, PhD., and Robert J. Henning, MD S is a clinical syndrome characterized by protracted prostration, pallor, coldness and moistness of the skin, collapse of the superficial veins, alterations in mental status, and suppression of the formation of urine.' The systolic arterial pressure is usually less than 90 mm Hg or has declined more than 50 mm Hg from the basal level and the urine flow is less than 20 ml/hour. The urine is typically iso-osmolar. The ratio between urine osmolality and plasma osmolality, which reflects the tubular concentrating function of the nephron, is characteristically less than 1.5. The basic mechanism underlying all forms of acute circulatory shock is reduction of effective blood flow and inadequate tissue perfusion with decreased delivery of oxygen to the capillary exchange bed.' The clinical signs of shock reflect primary perfusion failure. Reduction in peripheral blood flow accounts for cold, cyanotic extremities; reduction in cerebral blood flow for altered mental alertness; reduction in renal perfusion for diminution in both the quantity and quality of urine that is excreted; and reduction in coronary blood for compromised myocardial oxygen supply and electrocardiographic S-T WEIL AND HENNING f lytic enzymes and autodiges- metabolic oxygen, the anaerobic t is activated and this accounts of excesses of lactic acid and The magnitude of lactic acidosis severity of the oxygen deficit. therefore provides a quantitative en deficit and, in turn, of the failure. In patients who present perfusion failure, the concentrarial blood characteristically exWhen * lactate concentrations inmmol/L, survival progressively oximately 90% to (Fig 1). ore, is a sine qua non of oxygen represents the best single objecsion failure hock).^ n of Circulatory Shock cation of circulatory shock, we its in tissue perfusion originate gories of hemodynamic deficits: failure, defects in the distribuand vascular obstruction (Table k accounts for the vast majority irculatory shock in patients who it is due to a primary deficit in .* The volume of blood within ce is depleted to the extent that TABLE 1 Reclassification of Shock StatTyDe of shock Hypovolemic shock Exogenous Endogenous Cardiogenic shock Cause Blood loss due to hemorrhage Plasma loss due to burn, inflammation Electrolyte loss due to diarrhea, dehydration Extravasation due to inflammation, trauma, application of a tourniquet, anaphylaxis, and pheochromocytoma Myocardial infarction Cardiac failure Arrhythmia Distributive shock High or normal resistance (increased venous capacitance; selective or general) Bacillary shock Barbiturate intoxication CNS injury Ganglionic blockade Low resistance (arteriovenous shunt) Inflammatory vasodilation due to pneumonia, peritonitis, abscess; reactive hyperemia Obstructive shock (by anatomic site and mechanism a. Venacava b. Pericardium c. Cardiac chambers d. Pulmonary circuit e. Aorta 1. Compression 2. Tamponade 3. Ball-valve thrombus 4. Embolism 5. Dissecting aneurysm parenchyma, an acute reduction of plasma volume to WEIL AND HENNING WEIL AND HENNING TABLE 2 ng Central Venous Monitoring Guidelines forPressure Fluid Challenge Utilizing Central Venous Pressure Monitoring Fluid challenge: CVP, cm H20 (5-2rule) Fluid challenge: CVP, cm H20 (5-2rule) 4 4 cm H 2 0 2 1 4 cm H 2 0 <8 cm H20 200 ml x 200 ml x 10 min 4 4 cm H 2 0 \Peripheral 100 ml x 100 ml x 10 min 2 1 4 cm H 2 0 50 m~ x 50 m~ x 10 min/IV >5 cm infusion Following STOP >2 cm < 5 cm Observe for 10 min <8 cmCVP H20 During infusion 0-9 min >5 cm >2 cm 10 min Wait 1 2 cm 10 min \Peripheral 10 min 10 min/IV STOP Wait 10 min Wait STOP Continue infusion >2 cm < 5 cm Wait STOP >2 cm Continue 1 2 cm TABLE 3 should be discontinued. Following the infusion, if the infusion CVP has risen by less than 5 cm but more than 2 cm Guidelines for Fluid Challenge Utilizing Pulmonary Artery of H20, theifpatient observed3for a 10-minute inter- Diastolic or Pulmonary Artery Wedge Pressure Monitoring ng the infusion, the is TABLE val. Ifthan the CVP persistently exceeds cm H20 of the Utilizing Pulmonary mm Hg (7-3 rule) Fluid challenge: PPAW, PPAD Guidelines for2Fluid Challenge Artery m but more 2 cm is monitored but noArtery addi- Wedge starting value, the patient Diastolic or Pulmonary Pressure Monitoring 200 ml x 10 min Observe PPAD/PPAW 42 mm Hg or a 10-minute intertional fluid is administered. If it declines to within 2 for 10 min <16 mm Hg 100 ml x 10 min eds 2 cm H20 of the mm Hg (7-3 rule) Fluid challenge: PPAW, PPAD 216 mm Hg 50 ml x 10 min cm H20 of the starting value, the fluid challenge is nitoredresumed. but no Inaddieach instance, the pressure value 200 ml 10mm minHg Observe PPAD/PPAW 4imme2 mm HgDuring infusion 0-9x >7 STOP diately preceding the fluid challenge serves as the declines to within 2 for 10 min <16 mm Hg min 100 ml x 10 min reference measurement. Fluid is administered until 216 mm HgImmediately50 ml x >3 10< min he fluid challenge is follow7 mm Hg Wait 10 min either the hemodynamic signs of shock are corrected 10 min infuing >3 mm Hg Wait STOP pressure value imme- During infusion 0-9 >7 mm Hg STOP or the central venous pressure “5-2” rule is violated. sion 1 3 mm Hg Continue infusion llenge serves asrule theis employed min when measurements of A “7-3“ s administered pulmonary until artery diastolic (PPAD)or “wedge”>3(PPAW) follow< 7 mm Hg Immediately 10 min minute Wait infusion, the pulmonary artery diastolic presare available (Table 3 ) . The PPAD is a valid f shockpressure are corrected ing 10 min infu- >3 mm Hg sure or Wait STOP the pulmonary wedge pressure has increased indication of left-sided filling pressures in the absence 5-2” rule is violated. sion 1 3 mm Hg by less Continue infusion Hg but more than 3 mm Hg, the than 7 mm of pulmonary hypertension. However, when pulmopatient is observed for 10 minutes. If the pulmonary en measurements of nary diastolic pressure exceeds wedge pressure by pressure persistently exceeds 3 mm Hg of the starting AD)or “wedge” more than(PPAW) 5 mm Hg and if changes in PPAW not minute infusion, thedopulmonary diastolic pres- but fluid challenge is value,artery the patient is monitored Шок • Шок -­‐ симптомокомплекс, в основе которого лежит неадекватная капиллярная перфузия со сниженной оксигенацией и нарушенным метаболизмом тканей и органов. • Снижение АД не эквивалентно шоку Патофизиология Венозный возврат↓↓↓ Сердечный выброс ↓ ↓ ↓ ОЦК ↓↓↓ ↓ Давление крови в капиллярах ↓Осмотическое давление Увеличение тока жидкости из интерстиция в сосудистое русло (30 – 40 мл/ч) Патофизиология Сердечный выброс ↓ Активация барорецепторов и САС Увеличение выброса в кровь катехоламинов Стимуляция α-­‐ и β-­‐адренорецепторов Тахикардия Одышка Бледность кожных покровов Вазоконстрикция Регуляция тонуса гладкой мускулатуры Регуляция тонуса мускулатуры микрососудов Механизмы вазодилатации при шоке Патофизиология Спазм сосудов почек (олигурия) Нарушение МКЦ (мраморность кожи) Вазоконстрикция Нарушение кровоснабжения органов брюшной полости Некроз слизистой ЖКТ Стрессорные язвы Патофизиология Вазоконстрикция Гипоксия тканей Тканевой ацидоз Повреждение клеточных мембран Транслокация жидкости из кровяного русла в интерстиций Сладж-­‐синдром ↓ОЦК Синдром ДВС Образование микроэмболов Патофизиология • Нейро-­‐эндокринные сдвиги • Активация САС (повышенный выброс adr и noradr). • Активация ГГАС (массивный выброс АКТГ, кортизола, альдостерона, АДГ) -­‐ увеличение осмотического давления плазмы крови, усиление реабсорбции Na+ и Н2О, уменьшение диуреза и увеличение объема внутрисосудистой жидкости. Патофизиология • Нарушения метаболизма АТФ Глюкоза пировиноградная кислота анаэробный гликолиз Аминокислоты свободные жирные кислоты молочная кислота Метаболический ацидоз Накопление в тканях нарушение функции клеточных мембран Патофизиология • Гуморальные сдвиги высвобождением вазоактивных медиаторов гистамин, серотонина, Pg, NO, TNF, IL Ацидоз и гипоксия вазодилятация, увеличение проницаемости сосудистой стенки, выход жидкой части крови в интерстициальное пространство, снижение перфузионного давления. угнетение функции сердца, повышение возбудимости кардиомиоцитов, аритмии Патофизиология Изменения эндотелия капилляров гипоксическое набухание клеток адгезия с полиморфноядерными лейкоцитами • 1 фаза – ишемическая аноксия (сокращения пре-­‐ и посткапиллярных сфинктеров) • 2 фаза – капиллярный стаз (расширение прекапиллярных сфинктеров при спазме посткапиллярных венул) • 3 фаза – паралич периферических сосудов (расширения пре-­‐ и посткапиллярных сфинктеров) Мониторинг кислородного транспорта – основа для диагностики шока Интубация трахеи, ИВЛ, катетеризация центральной вены и артерии Седация, миоплегия Контроль ЦВД Менее 8 мм рт.ст. 8-­‐12 мм рт.ст. Контроль среднего АД Менее 65 и более 90 мм рт.ст. 65-­‐90 мм рт.ст. Контроль венозной сатурации Более 70 % Цель достигнута Менее 70 % Инфузия кристаллоидов/ коллоидов Вазоактивные препараты Гемотрансфузия до гематокрита более 30 % Инотропная поддержка Ранняя целенаправленная интенсивная терапия у пациентов с сепсисом в первые 6 ч после установления диагноза Ранняя целенаправленная терапия Rivers E., Nguyen B., Havstad S. et al. Early goal-­‐directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and sep‰c shock. New Engl. J. Med. (2001). 345 (19): 1368-­‐1377.